Abstract

Using 1,234 microfinance firms in 106 countries, this study investigates the determinants of default on the microcredit debt obligation of borrowers. Using the variant of extreme bounds analysis that systematically tests the fragility of coefficient estimates, we examine the importance of 42 variables in explaining default risk. At the micro level, the results from the modeling of model uncertainty reveal that regulation, cost per loan/cost per borrower, loan balance, borrower per loan officer, and the number of loan officers are robust factors. From the macroeconomic context, the time required to start a business and human capital are the determinants of default on debt obligations.

Introduction

It is often argued that the credit needs of the relatively poor are not met by the commercial banks because of lack of adequate loan guarantees (Hollis and Sweetman Citation1998).Footnote8 The provision of small loans to fight poverty by generating self‐employment projects is among the core objectives of microfinance institutions (MFIs). Having profit nature as well as social nature, MFIs have remained special financial institutions.

As the roles of these institutions have gone beyond profit making to enhancing entrepreneurial behavior and economic development through poverty reduction, job creation, and self‐empowerment, MFIs have become an integral part of the system that strives to reduce poverty and income inequality by encouraging entrepreneurial activities. However, efficiency and productivity of these institutions are important in their sustainability and survival. Thus, financial viability is important to MFIs in order for them to achieve a broader range of objectives.

Thus, this article aims to contribute to the existing knowledge by providing a broad overview of the potential determinants of default in microcredit debt obligations. The prediction of default among borrowers is certainly a difficult task, but this is of interest to credit providers. A large part of the literature on default risk has concentrated on sovereign default, corporate default, and banking crises (see Reinhart and Rogoff Citation2013). Studies on loan default have concentrated more on mega‐banks with little emphasis on MFIs.

We contribute exclusively to studies on default risk by focusing on MFIs. The study becomes more novel by taking an imperative step to examine if confidence at all can be established from the conclusion drawn from the paper. In contrast to the existing methodologies adopted in the existing studies on default risk, we use the extreme bounds analysis (EBA) to determine which of the determinants of default risk is fragile to minute changes in the conditioning information set. By using 1,246 MFIs in 106 countries, we contribute strongly to the literature by generating robust determinants of loan default.

Our methodological contribution is strengthened by the use of the variant of EBA to generate estimates that are robust to changes in the information set of each predictor in a pool of independent variables. A complete specification in which variables are held constant in the conduct of econometric tests is relevant as the conditioning information set may determine the state of the coefficients estimated in an empirical analysis.

From a pool of micro and macro determinants, we run a series of regression on 42 variables using regional dummies to capture fixed effects. A number of studies that evaluate the failure or success in MFIs are present in the literature. Some of the determinants are identified in Ahlin, Lin, and Maio (Citation2011); Cull, Demirgüç‐Kunt, and Morduch (Citation2007); Drexler, Fischer, and Schoar (Citation2014); van den Berg, Lensink, and Servin (Citation2015).Footnote9 Our study differs from these studies by focusing on loan default rather than success in general.Footnote10 We contribute to the literature by focusing on the potential micro‐institutional and macro‐institutional determinants of default. Thus, the study captures the contribution of macroeconomic factors to default on debt obligations among microcredit borrowers. In addition, the study models directly, the contributions of micro‐institutional factors to loan default.

At the micro level, the determinants of loan default have concentrated mainly on categorical information relating to the borrower. While few categorical variables are employed, quantitative approach is employed by using information as contained in the balance sheet of these institutions. These determinants are micro‐institutional factors, characteristics of the borrowers, the lending institution, and its workforce. In contrast to existing studies that depend on micro‐institutional variables, macroeconomic determinants are introduced as additional explanatory variables. These factors include economic condition, financial condition or the level of financial development, and macro‐institutional factors.

We contribute to knowledge on loan default by capturing outright default through loan loss rate (LLR). In addition, we further examine loan repayment performance by using the portfolio at risk (PAR) after 90 days. This is an early indication of default. These variables measure default risk in MFIs.

Background

In most countries with a less developed financial system, MFIs have continued to emerge. Apart from outreach and sustainability, financial viability occupies a pivotal position in the evolution of MFIs. An agreed guideline on the definitions of microfinance terms such as asset/liability management, sustainability/profitability, efficiency/productivity, and portfolio quality is provided by consensus group, which includes donors, private voluntary organizations, multilateral banks, and microfinance rating agencies (CGAP Citation2003).

The role of MFIs largely involves the provision of credit and saving to alleviate poverty and financial constraints among the poor (e.g., Khandker Citation2005; van Rooyen, Stewart, and de Wet Citation2012). In achieving this objective, the maximization of loan repayment is necessary for each MFI (e.g., Cull, Demirgüç‐Kunt, and Morduch Citation2007; Wenner Citation1995 on loan repayment). Being beneficial not only to the borrowers, it may ensure the financial sustainability of these lending institutions. This is highly valuable as it may encourage MFIs to lower interest rate on borrowing, which depicts lower borrowing cost of credit and increased access to finance. This may also lead to a smooth and successful operation of MFIs as their performance in terms of repayment is important for donor and international funding agencies.

Loan default among MFIs can be identified through their portfolio quality. Portfolio quality is defined to include PAR (PAR/gross loan portfolio), risk coverage ratio (loan loss reserves/PAR), write‐off ratio (write‐offs/average portfolio), and provision expense ratio (loan loss provision expense/average portfolio).

PAR measures the outstanding amount of all loans with principal past due by a number of days. Restructured loans may appear in this measure as higher risk is attached to such loans. Write‐offs are loans deducted from the balance of the gross loan portfolio because of the likelihood of non‐repayment. An adjusted ratio may be used to accommodate differences in write‐off policies. The risk coverage ratio measures the loan loss allowance provided in the PAR. The age of the PAR might be considered while making such provisions. The loan‐loss provision expense is a non‐cash expense used to generate or expand the loan‐loss allowance on the balanced sheet.

Repayment incentives such as collateral and/or personal guarantees may serve to ensure against wilful default, thus increasing repayment incentives. However, the difficulty in acquiring adequate collateral is an important issue. The loss of access to future loans can be an alternative repayment incentive. If bank credit record is available and accessible, this can help MFIs to identify defaulters and restrict credit provision to such borrowers. More flexible repayment schedule and an increase in loan size are other incentives that can be used to improve repayment performance (see Vogelgesang Citation2003). Thus, in this study, we examine the default risk using the LLR (value of loans recovered/loan portfolio, gross, average) and loan repayment performance using the PAR.

Conceptual Framework

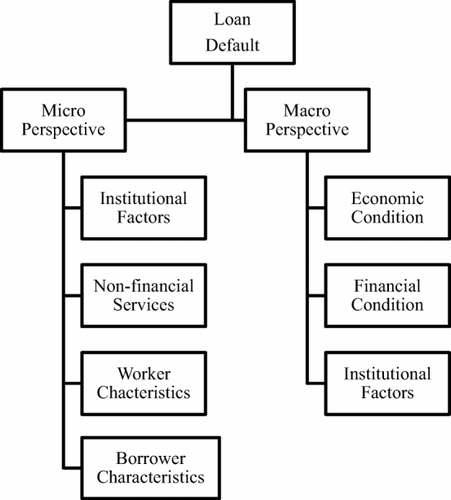

In this section, we present an overview of related studies and their associated theories. Given the nature of the work, we focus on variables as shown in previous studies as indicators of loan repayment/default risk in MFIs. This necessitates the inclusion of various related studies on MFIs. We present the hypothesis and a discussion on these indicators based on previous studies. In Figure 1, we present the links between existing studies and this current study. The figure depicts the importance of microeconomic and macroeconomic factors in predicting default from a debt obligation. At the micro level, the broad categories of these factors are identified to include institutional factors, non‐financial factors, and characteristics of the borrowers, the lending institution, and its workforce. At the macro level, the relevant factors include economic condition, financial condition, or the level of financial development and institutional factors.

In Table , we present the relevant studies and the important variables in these studies that help to explain loan default among borrowers of MFIs. Following these existing studies, we develop the hypothesis that microlevel and macrolevel factors are important in explaining the loan default among MFIs. We present a more general overview by pooling a large number of determinants together and tracing out the most relevant ones or the variables that survive the test by retaining the sign of their coefficients in thousands/millions of regression.

Table 1. Summary of Literature

Micro‐Perspective to Default Risk

The number of MFIs has increased over some decades ago owing to the interest of commercial banking bodies, non‐governmental organizations (NGOs), cooperatives, financial companies, and credit unions on the survival of MFIs. The commercialization of MFIs is anchored by the argument that the risk of financial loss, such as outright default, debt restructuring, and the present value of expected recoveries are low relative to returns. In this subsection, we present the discussion on microlevel indicators of default risk and some relevant theories on loan default. We discuss studies that examine institutional/MFIs specific factors such as regulation, production features, non‐financial service factors such as training, borrower features such as information asymmetry and characteristics of the MFIs' workers.

MFI‐specific, regulatory and institutional variables may affect the performance of MFIs. In their study, Hartarska and Nadolnyak (Citation2007) reveal that regulatory involvement has no direct impact on performance in terms of outreach and sustainability. Thus, the transformation of MFIs into regulated financial institutions may not generate an improvement in the financial results of these institutions as well as their performance in terms of sustainability. Drawing from previous studies, they argue that while positive and negative consequences abound if there is a lack of regulation, the establishment and operation of these institutions become easier. However, regulatory ambiguity induces vulnerability of MFIs to regulatory discretion.

With impressive loan repayment rates, MFIs attend to over 100 million clients (Cull, Demirgüç‐Kunt, and Morduch Citation2009). Though regulation can be achieved with costs, the call for regulation is invoked because of the rapid growth of MFIs. While providing the distinction between prudential and non‐prudential regulation, Christen, Lyman, and Rosenberg (Citation2003) offer a discussion on the trade‐offs in microfinance regulation. They explain prudential regulation as one that aims to protect the safety of small deposits in financial institutions and the wellbeing of the entire financial system. In a myopic view, microfinance might not pose a risk to the stability of the financial system as its assets are relatively less in comparison to mega‐financial service providers. However, some MFIs receive deposits from the public, of which many of the depositors are poor. Thus, they argue that prudential regulation should be invoked when MFIs receive retail deposits from the public in order to protect the safety of these depositors. Cull, Demirgüç‐Kunt, and Morduch (Citation2011) show that regulation can be costly, but it enhances the banking functions of MFIs. Evidently, profit‐oriented MFIs maintain profit rate by curtailing outreach to customers and women that are costly to reach.

Godquin (Citation2004) argues that a better repayment performance should associate with joint liability, which can manifest through peer monitoring, peer pressure, and peer selection. Thus, greater efficiency because of group dynamism, which is linked to social ties and group homogeneity will increase the repayment performance. An empirical examination of the effects of group dynamics can be seen in Wenner (Citation1995). He examines repayment performance and selection mechanisms in 25 Costa Rican credit groups. While examining the use of local information by group members in screening their peers, he shows that private information as used by group members in selecting their peers has a beneficial effect on repayment performance. He states that group lending might be beneficial to improve information flow, but it is a cost‐sensitive institutional design. Zeller (Citation1998) provides support for group lending. By employing information on 146 credit groups in Madagascar, he reveals the beneficial effect of internal rules of conducts (peer selection) on repayment performance. His investigation of the benefits of intragroup pooling or risky assets or projects supports the beneficial impact of social cohesion.

Other aspects of institutional and MFI‐specific factors include production and locational features. Paxton (Citation1996) links a better repayment performance to urban locations, market‐selling activities, and other credit sources. Khandker, Khalily, and Khan (Citation1995) examine if a default on a debt obligation occurs by random or it is influenced by the erratic behavior of borrowers (irregular repayment of loans) and branch‐level efficiency/characteristics that define local production conditions. They show that area characteristics are partially important on overdue loans of Grameen Bank in Bangladesh. Thus, a low default rate correlates positively with primary educational infrastructure, road width, rural electrification, and commercial bank density. They also find that the loan default rate increases with the length of operation of a branch in an area. This occurs due to decreasing marginal profitability of new projects or decreasing power of dynamic incentives (defaulting borrowers are able to acquire or renew credit since they are not systematically denied access to credit).

As he examines the relationship between non‐financial services, group lending, dynamic incentives, and repayment performance, Godquin (Citation2004) shows that the provision of non‐financial services is costly but it enhances loan repayment. These non‐financial services can include access to basic literacy, professional training, marketing, and health. Other studies on non‐financial services such as business training and financial literacy are explored in Berge, Bjorvatn, and Tungodden (Citation2015) and Drexler, Fischer, and Schoar (Citation2014). Chakravarty and Pylypiv (Citation2015) present a study on the relevance of profit characteristics of MFIs to the repayment rate of borrowers.

The characteristics of the borrowers are important in loan repayment performance. Vogelgesang (Citation2003) shows that the chances of default for clients with multiple loan sources are higher than others. Information asymmetries can be a major factor that affects repayment. This can take the form of moral hazard or adverse selection, which limits the proportion of loans repaid. Moral hazard can occur such that the borrower relents in maximizing the use of such credit or apportion the credit to undesirable consumption. Adverse selection can exist such that the identification of borrowers with undesirable features is circuitous. A strategic default might be common for borrowers who have adequate money to fulfill their debt obligation. This can occur if MFIs are not strict to enforce loan repayment as little or no power is apportioned to them by the legal system. A low collateral requirement can induce strategic default.

An important component of the borrower characteristics is the gender of the borrower. The literature suggests that the targeting of women generates high repayment rates among MFIs. D'Espallier, Guérin, and Mersland (Citation2011) find that female clients of MFIs have fewer provisions, fewer write‐offs, and lower portfolio risks.

A relevant factor of a loan repayment rate is the workers' characteristics (van den Berg, Lensink, and Servin Citation2015). They show that in improving repayment rates in microfinance, loan officers play a crucial role. They state that the inducement of borrowers to repay is better achieved by using male loan officers than female loan officers. They argue that the reason for such observation might be because men face fewer problems traveling through unsafe places, working late, and enforcing repayment while working as counsellors.

H1: From the micro‐perspective, institutional, worker and borrower features affect default risk.

Macro‐Perspective to Default Risk

In this subsection, we present a discussion of macrolevel indicators of default risk‐focusing on economic, financial, and institutional factors. What constitutes success in MFIs has been a subject of interest to many researchers. In recent periods, the examination of the success of MFIs in relation to macroeconomic context has become essential to generate a clearer picture of factors that surround the failure or success in operation.

The economic conditions of a country have been shown to be relevant to the failure of MFIs. Hermes and Meesters (Citation2011) show that financial development and economic growth associate with the cost‐efficiency of the MFIs. Studies that relate the performance or in a broader perspective the activities of MFIs to macroeconomic outcomes or conditions of the country in which they operate are currently emerging. In their study, Ahlin, Lin, and Maio (Citation2011) examine the importance of economic conditions to the performance of MFIs. They find a complementarity between the macroeconomy and MFI performance. Examining the importance of country context to MFI performance, they reveal that stronger growth aids in lowering cost incurred by MFIs. In financial deeper economies, they find that MFIs have lower operating and default costs and charge lower interest rates.

The question of the contribution of a growing or recessing economy to the success and the sustainability in the provision of services to clients of MFIs is an important one. As discussed in Waller and Woodworth (Citation2001), the main conclusions of previous studies on the importance of the macroeconomy revolve around the requirement of a stable economic growth, fiscal discipline, and low levels of inflation to attain viability in the operation of MFIs and the success of their clients. As argued by Ahlin, Lin, and Maio (Citation2011), the creation of potential opportunities for existing microentrepreneurs to expand and fill new niches can occur if an economy experiences high growth. In addition, the survival of such institutions may depend largely on poor economic stance such that default on loan obligations become reduced as economic opportunities do not obstruct the relationship between MFIs and their borrowers because of weakened borrowers' incentives to repay.

The relevance of institutional specific practices to the success of MFIs is an important research question. Ahlin, Lin, and Maio (Citation2011) examine the broader institutional environment and the performance of MFIs. On the importance of macro‐institutional environment, they show that lower corruption relates to faster extensive growth in MFIs while regulatory quality (RGQ) and voice/accountability relate to higher default rate. Hermes and Meesters (Citation2011) show that political and institutional environments have no clear association. Corruption may hinder the expansion of microenterprises and consequently, limiting the poor to have sufficient and readily access to micro‐loans. As borrowers are aware of no serious punishment on debt default, non‐regulated practices may affect loan delinquency and repayment.

In the case of Bangladesh, Khalily (Citation1993) undertakes an investigation on how rural loan recovery relates to political intervention. In stimulating loan recovery, they show that political interventions undermine the effectiveness of positive real interest. The argument put forward in his investigation is that loan delinquency can occur if borrowers are protected politically by their sponsors. They state that the intervention of government in rural loan allocation and recovery through financial policies, government officials, and political leaders has detrimental effects on loan recovery. As a tool of getting reelected, the government may decide to intervene in rural lending decisions with the aim to influence the perceptions of voters. He argues that through sociopolitical leaders, lending, and rural financial policies, the government can use financial benefits to influence the voting decision. In addition, strict borrower selection process and proper loan recovery procedure may not receive adequate support during an election period.

The financial state of the economy is also important in the examination of failure among MFIs. In a case study of the performance of Bank Rakyat Indonesia (BRI) in the wake of the late‐1990s Indonesian financial crisis, Patten, Rosengard, and Johnston (Citation2001) find no evidence for a change in the repayment rates of BRI's micro‐loans. However, they record a little increment in the BRI's nominal interest rates on micro‐loans, which rise to about 13 percentage points in one year. As achieving social impact as well as earning a return on investment is the dual goal of some MFIs, a deeper knowledge of the determinants of financial success becomes important, as financial returns are relatively valuable to these MFIs.

It can be assumed that a growing economy may lead to increments in business opportunities and the development of new investment projects by increasing investment incentives for small‐scale enterprises. With the consequential increase in the demand for loans and an improvement in repayment performance, an increase in cost efficiency of MFIs is inevitable. The costs of holding loan loss reserves and the costs involved in loan recovering are reduced by such improved loan repayment recovery. Loan repayment performance may adversely be affected by an economic recession, as profits accruing to borrowers are insufficient to finance new projects thereby inducing deliberate loan default. The demand for domestically produced goods from small‐scale entrepreneurs may act to ameliorate the effect of an adverse economic state and thereby raises the demand and repayment of microcredit from MFIs.

H2: From the macro‐perspective, economic, financial and institutional factors affect default risk.

Data

From narrow and broad perspectives, we examine the determinants of default for which the data are available. These variables are selected following the discussion on the conceptual framework. At the micro level, we employ variables that fall under institutional/MFI‐specific factors, borrower, and worker characteristics. Thus, we obtain data on regulation (RGL—coded as 1 for regulated institutions and 0 otherwise), profit status (PRS—coded as 1 for profit and 0 for non‐profit oriented institutions), and financial intermediation (FIM—coded as 1 for intermediation (high and low) and 0 otherwise. Other variables employed include PAR > 90days, LLR, borrowings (BRS), average loan balance per borrower (ALBB), cost per borrower (CPB), borrowers per loan officer (BPL), number of active borrowers (NAB), borrower retention rate (BRR), cost per loan (CPL), gross loan portfolio total (GLP), number of loan officers (NLO), number of loans outstanding (NOL), percentage of female loan officers (FLO), number of offices (OFF), percentage of female borrowers (FBS), and staff turnover rate (STO).

These firm‐level data are from the Mix Market and are taken from the balance sheet of the firms. We concentrate on loan default using the LLR and the PAR > 90days. The PAR > 90days is conventionally used to measure portfolio or repayment performance. Thus, these variables help to generate the relationship between default (non‐repayment of loans) and its determinants from micro‐ and macro‐perspectives.

At the macro level, we obtain data on institutional factors‐control of corruption (CPTN), government effectiveness (GEF), political stability (PLST), voice and accountability (ACCT), RGQ, internally displaced person‐internal conflict (ICFT), business regulatory environment (BRE), and the strength of legal rights index (SLR). These five institutional factors are obtained from the survey of the Worldwide Governance Indicators. We employ the standard normal units of each indicator, which range from −2.5 (weakest) to 2.5 (strongest) among all countries worldwide. From 31 different data sources, these data are based on several hundred variables that capture governance perceptions as reported by public sector organizations worldwide, survey respondents, NGOs, and commercial business information providers (Kaufmann, Kraay, and Mastruzzi Citation2011).

We also obtain data on economic and financial variables and these include; the consumer price index (2010 = 100), agriculture value added (AGRV), real GDP per capita (RGDPC), cost of business start‐up procedures/percent of GNI per capita (CBS), fiscal policy rating (FPR), GINI index (GINI), foreign direct investment net inflows/percent of GDP (FDI), domestic credit to private sector/percent of GDP (DCP), industry, value added/percent of GDP (IVA), manufacturing value added/percent of GDP (MVA), poverty gap at national poverty lines (PVG), private credit bureau coverage/percent of adults (PBC), procedures to enforce a contract (PENC), the real interest rate (RIR), services value added (SVA), time required to start a business (TRB), and a measure of human capital‐secondary school enrolment (EDU). The log of these variables is employed while the growth rate of RGDPC and the Consumer Price Index (CPI) are employed. These country‐level data come from the World Bank.Footnote11

Based on the availability of microfinance data, the study period covers 1996–2014. Over this period, we employ a panel of MFIs that include 1,246 MFIs from 106 countries. The MFIs employed have at least a four‐year observation.

Methodology

To generate the robust determinants of default in MFIs, the study uses the variant of the EBA of Leamer (Citation1983). Adapting the variant of EBA of Baxter and Kouparitsas (Citation2005), we capture fixed effects using both firm and country indicator variables. The econometric specification of the EBA takes the following format

where

is either the LLR (write‐offs—value of loans recovered)/loan portfolio, gross, average, PAR after 90 days,

is a set of variables that appear in regression that involve default or loan repayment performance (free variable) and could be empty,

is the variable of primary interest,

is the subset of variables, which are selected from a pool of independent variables identified from other studies as potentially essential determinants of default risk.

For a particular M‐variable, the performance of an EBA requires varying the set of Z‐variables included in the regression. From the estimations, the EBA generates the highest and lowest values of confidence intervals constructed from the estimated

. The robustness of

to changes in the conditioning information set is tested in the EBA. The lower extreme bound is the lowest value of

minus two standard deviations and the upper extreme bound is the highest value of

plus two standard deviations. The robustness of

requires both upper and lower extreme bounds to have the same sign. The estimation of an equation with a set of variables limits the analysis to a small subset of the potentially numerous models that could have been estimated. The consideration of the entire range of models in each and of which the variables of interest and any one linear combination of other doubtful variables are to be included becomes a more reliable approach. In this case, a conclusion can be reached if inferences on a particular variable of interest remain unchanged otherwise; the inferences are fragile to be reliable. Thus, a determinant of default will possess statistically significant coefficient that has the same sign when the conditioning information set is changed.

We follow similar technique as given in Levine and Renelt (Citation1992). We allow the I‐variable to be empty while the Z‐variable is restricted for up to four variables. Thus, the system determines which variable is essential. In the second case, we use the growth of the real Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita (GRGDPC) as the I‐variable. At the macrolevel analysis, we restrict variables that may measure the same phenomenon as the Z‐variable.

Results and Discussion

We begin the exercise by applying the EBA separately for the microlevel variables and then for the macrolevel variables. Thereafter, all macro and micro variables are pooled together. At this stage, we also allow the set of I‐variables to be empty. At the microlevel, all variables are included while at the macrolevel, variables that tend to measure similar phenomenon are excluded. Using the LLR as the determined variable, microlevel variables have little or no correlation with each other while some macroeconomic variables show a correlation with each other (correlation matrix is not shown). The Z‐variable is restricted to 4 at most. This minimizes multicollinearity, though multicollinearity is accounted for using the variance inflation factor. The critical value is set at 10 percent. Among the 17 microlevel variables, 8 explanatory variables have significant lower and upper bounds while 5 variables remain robust (Table ).

Table 2. Micro Determinants of Default Risk

The CPL and the CPB reveal a positive relationship with default. The positive relationship is expected as increasing cost will make it likely for lenders to charge higher interest rate. The implication is higher chances of default as borrowers may find it difficult to fulfill their debt obligations. Surprisingly, the NLO has a positive relationship with default risk. This result is partially explained following the findings of van den Berg, Lensink, and Servin (Citation2015), who show that in improving repayment rates in microfinance, loan officers play a crucial role. In the case that peer monitoring is expensive, lenders may not abandon their monitoring role to peer manager among group members. Thus, efficiency and more aggressive loan recovery strategy are likely to be important in the reduction of default risk.

The loan balance and the number of borrowers per loan have a negative relationship with default risk. This implies that the number of borrowers is not detrimental to the operation of the MFIs. With loan repayment strategies of MFIs, one expects lower default rate, however, an increasing number of micro‐lenders find it difficult to maintain high repayment rates. The evidence in this paper does not support the argument that having more borrowers leads to default risk.

PRS and regulation have significant coefficients at the lower and upper bounds, but are insignificant at the base. Thus, additional variables as shown in Table are needed to generate significance of their coefficients.

Table provides the EBA of the M‐variables at the macro level using the LLR as a measure of default risk among MFIs. Only a few variables at the macro context robustly correlate with the risk of default. For some conditioning sets, the coefficients of GEF and agricultural value added relate negatively with the probability of default risk. However, the results are fragile when only the M‐variable is used in the base equation. Among the macroeconomic determinants of default risk, human capital and TRB relate negatively with default risk. Thus, human capital is important in default risk. The results remain consistent when all the micro and macro variables are pooled together in a single equation (Table ).

Table 3. Macro Determinants of Default Risk

Table 4. Micro and Macro Determinants of Default Risk

The result shows that educational background is important in micro‐business development and performance by lowering default risk. To transform a financial capital into viable investments, Berge, Bjorvatn, and Tungodden (Citation2015) suggest that business training is important. They reveal that financial capital intervention and human capital intervention have a strong impact on the entrepreneur, especially for male entrepreneurs. The ability to manage a business and appropriately use a loan for its purpose requires some informal or formal training. The relationship shows that education or training of loan borrowers, especially for these micro‐borrowers is important in reducing loan default. This is important in financial management as shown in Drexler, Fischer, and Schoar (Citation2014). In their study, they examine the causal link between financial outcomes and financial literacy. In the Dominican Republic, they conduct a randomized control experiment to assess the importance of financial training programs on individual and firm‐level outcomes among micro‐entrepreneurs. Contrasting standard accounting training (classroom training) and the rule of thumb‐based training (visit after training) in their experiment; they show that the latter has significant improvement in their financial management and the internal consistency and accuracy of the numbers they report. Though our study generates the impact of human capital from macro context, this study helps to provide a strong support for the importance of human capital while confirming the importance of education and/or business training.

The TRB is an essential ingredient in default risk. An increase in late payments and outright default in recent years can arguably be linked to so many factors such as economic crisis, rising competition, over‐indebtedness, and behavior of clients such as moral hazard. Vogelgesang (Citation2003) shows that the chances of default for clients with multiple loan sources are higher than others while better repayment behavior is uncovered for clients with given characteristics in areas with a higher supply of micro‐loans and a higher competition. The availability of numerous lenders gives clients the opportunity to choose between different lenders and may lower the good stand they maintain with a particular loan provider. Thus, time to start a business becomes important as clients' tendency to exhibit moral hazard may increase with a delay in project implementation.

Over the past few decades, MFIs have received great funding and attention from various organizations. While some have attained high growth in reaching to a large number of borrowers, failure has marked the operation of some MFIs.

In the case of low‐income developing countries, researchers have extensively discussed issues that relate to loan recovery. As detailed in Khalily (Citation1993), the assumptions about loan provided to the borrowers in these Least Developed Countries (LDCs) are that rural borrowers are very poor to repay, rural loans are risky, political intervention in rural financial markets deters loan recovery, lending policies deter repayment performance. In addition, lenders' unwillingness in loan recovery, loan targeting, and management abilities of employees of the banking institutions affect loan recovery.Footnote12 While these factors are essential, the results as documented in this section lay emphasis on the cost of a loan, educational ability of borrowers, and the time required to use the borrowed loan for the purpose of its acquisition. A delay in the implementation of the actual plan for the borrowing may lead to the diversion of the microcredit to unprofitable ventures.

In Table , the study repeats the estimations as documented in Table (micro/firm‐level) and Table (macro context) by using the GRGDPC as the I‐variable. The result as shown below reveals that GRGDPC explains some variations in the proportion of loan loss (LLR). The standard errors are in parenthesis; n represents the number of observations while the star sign represents 1 percent significance level.

Table 5. Micro and Macro Determinants of Default Risk (RGDPC = M‐Variable)

The results of the EBA in Table strengthen the previous findings where the set of I‐variables is empty. In this case, all the estimates remain robust in each specification. At the firm‐level, CPL, the CPB, the loan balance, the number of borrowers per loan, and the NLO relate with default risk. Additional explanatory power is achieved in the case of regulation, which previously has similar upper and lower bounds, but less statistically significant at the base equation. Thus, compared to non‐regulated firms, regulated firms have a lower LLR.

The results as obtained in this study shows that regulation is an important determinant of default risk or loan repayment performance. This gives new evidence in contrast to Hartarska and Nadolnyak (Citation2007), who reveal that regulatory involvement has no direct impact on performance in terms of outreach and sustainability. Thus, the transformation of MFIs into regulated financial institutions may not generate an improvement in the financial results of these institutions as well as their performance in terms of sustainability. Our result is strengthened by the findings of Cull, Demirgüç‐Kunt, and Morduch (Citation2011). They show that regulation can be costly, but it enhances banking functions of MFIs. Evidently, profit‐oriented MFIs maintain profit rate by curtailing outreach to customers and women that are costly to reach.

Agricultural value added improves in its explanatory power but remains fragile at the 10 percent critical value. This result concurs with the findings of Ahlin, Lin, and Maio (Citation2011) who shows that the number of procedures for contract enforcement negatively associate with the loan loss expense rate, a result that seems hard to interpret but proper interpretation will require asymmetric evidence (low or high time requirement from micro‐perspective). At the macrolevel, human capital and TRB have strong relationships with default risk.

Institutions and Loan Default

Using panel fixed and random effect models, this section examines the contributions of the CPB and human capital to default risk when institutional factors are present. Thus, this section focuses on loan default in the presence of institutional risk factors. We examine how the EBA generated variables relate to default risk in the presence of institutional factors obtainable in the areas that these MFIs operate. Institutional factors are not robust determinants in the EBA analysis, but strikingly, the NLO relates positively with the LLR. Thus, efficiency is likely to be important in the default link. With a major concentration on the institutional risk factors, we examine the relationship between default risk, GEF, PLST, CPTN, internal conflict, ACCT in combination with the determinants of default risk (human capital, the NLO, CPB and outstanding loan).

A confirmatory check is undertaken by using the two‐step generalized method of moments (GMM) (Blundell and Bond Citation1998) to account for endogeneity. The maximum instrument for the dependent variable is limited to four to avoid instrument proliferation. The post‐estimation tests are valid, as shown by the results. We present the Ordinary Least Squares estimates for each of the models in Table while Table has the GMM, fixed, and random effects models.

Table 6. Institutional Factors and Default Risk (OLS)

Table 7. Institutional Factors and Default Risk

The results in Tables and show that the CPB is significant to increase default risk (LLR) or loan delinquency (PAR) while regulation significantly lowers default risk among MFIs. PLST, ACCT, and the CPTN help to lower the risk of default in a microcredit debt obligation. Internal conflict and GEF are insignificant. Attaining self‐sufficiency will demand proper portfolio management. Arrears (late loan) and delinquent loans (written off) can express default in debt obligation of clients. A default on loan obligation can be linked to institutional factors such that a microenterprise that is willing to observe the rule of law will strive to meet its debt obligation without testing the seriousness of MFIs in collecting loan repayments. Default on loan repayment can occur on the basis that the loan is issued under favoritism. The argument is that a corrupt MFI officers can influence the write off of loans lent to his/her friends or relatives. Thus, the question of how institutional factors shape the behavior of borrowers is important.

The provision of affordable credit is expected to enhance entrepreneurial abilities and consequently improve performance. The measurement of productivity/performance of MFIs occupies a central position in evolutionary studies of MFIs. More recently, studies that relate institutional context to entrepreneurship are present. Bowen and De Clercq (Citation2007) hypothesize that the institutional environment of a particular country will influence the allocation of entrepreneurial effort and in particular, this will affect the extent to which entrepreneurs direct their efforts toward high‐growth activities.

The results show that default risk increases with the RIR and the NLO. FLM, human capital, and the FBS aid to lower default rate. The literature suggests that the targeting of women generates high repayment rates among MFIs. D'Espallier, Guérin, and Mersland (Citation2011) find that female clients in MFIs have fewer provisions, fewer write‐offs, and lower portfolio risks. In addition, enhanced repayment among women remains stronger among regulated MFIs, NGOs, and individual‐based lenders. The promotion of women empowerment through microcredit provision is a promising path in the alleviation of poverty.

A lower default risk among female borrowers is confirmed in the analysis. This helps in providing further support on the role of women in the path of poverty alleviation, poor child education, and training. This result has important gender policy implications for development agencies and microfinance providers. The targeting of women in order to avoid default on a microcredit debt obligation becomes a better strategy in achieving sustenance and continuity of MFIs. Loan extension to women becomes desirable in solving other social issues such as the reduction of gender inequality as women become reliable entrepreneurs. Their act of enterprising will help in ensuring economic and PLST through the creation of employment for unemployed youths, especially in developing countries where MFIs have numerous goals inclusive of reaching the poor.

Conclusion

A few studies do focus on the relationship between the performance of MFIs and the macroeconomy while many examine the performance of MFIs from micro‐perspectives including field experiments. This paper provides an overview of the strength of macroeconomic and microeconomic elements in influencing the default risk in MFIs. Using 1,234 microfinance firms in 106 countries, we apply the variant of EBA to systematically test if the results as proposed by theoretical and empirical scholars are robust to changes in the information set of various specifications.

By focusing on MFIs, we extend the literature of loan repayment performance by capturing outright default through LLR. In addition, we further examine loan repayment performance by using the PAR after 90 days. The relevance of institutional risk factors is further examined in addition to the EBA analysis. From the micro context, the cost of a loan, the NLO and regulation are the determinants of default risk. From the macro context, human capital and the TRB are the determinants of default on debt obligations. The signs of the variables are unchanged with the inclusion of a free variable. We conclude that while institutional factors are relevant in loan repayment performance, they are not the strong determinants of default risk.

A deeper understanding of the determinants of financial success is necessary, as this might be central in defining the capability of MFIs to maintain their reach and sustainability. It is essential for bank managers to understand the causes of loan default among their clients. As achieving social impact as well as earning a return on investment is important to MFIs, the result provides an argument in support of regulation. This has been viewed as an important factor in the protection of small depositors and the financial system as a whole (see (Christen, Lyman, and Rosenberg Citation2003; Cull, Demirgüç‐Kunt, and Morduch Citation2011). Thus, an improved regulatory mechanism goes beyond the maintenance of financial stability to ensuring adequate loan disbursement and monitoring. Thus, the study advocates for the regulation of MFIs to enhance efficiency in terms of loan monitoring and the reduction of the financial burden to the poor, which is inevitable in the case of loan default and financial instability.

The result shows that human capital is important to loan recovery and repayment. An earlier study by Drexler, Fischer, and Schoar (Citation2014) shows the link between financial outcomes and financial literacy. The role of human capital in economic growth, firm performance and enterprise development and management cannot be over‐emphasized. In essence, it becomes essential for microfinance providers and their supporting agencies to work towards the provision of basic training to loan borrowers and especially to the poor in developing countries. The provision of facilities and the equipment of the masses especially small business owners with the knowledge on how to manage successfully their businesses are appropriate steps in building healthy borrowers. The provision of educational support to small business owners who utilize the services of these MFIs should be the core aim of government human empowerment programs and various aid and development agencies in ensuring human capacity and knowledge building.

The TRB is a determinant of loan default or repayment. The study also lay emphasis on the reduction of the bureaucratic process required before a business is allowed to be established or better still, an urgent attention should be given to these micro‐borrowers by various authorized agencies. The paper suggests that MFIs should devise appropriate ways of reaching its customers at a lower cost.

This study is limited by employing more rigid EBA of Leamer (Citation1983). It is essential that future research may use a more flexible EBA to systematically test if more variables will be robust to changes in the information set. In this case, variables that emerge as the determinants of default risk will be relevant to policy makers. Another limitation of this study is that it focuses on a pool of countries. It may be necessary for future studies to examine the relevance of these variables across regions or smaller group of countries. Country to country analysis may also be relevant if the data are available to permit country‐level analysis. The analysis is limited by the availability of data as other important variables are not captured. It becomes relevant for qualitative and experimental studies to focus on the development of indexes to be used as inputs in quantitative analysis of the operation of MFIs.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

John Nkwoma Inekwe

John Nkwoma Inekwe is a VC Research Fellow at the Centre for Financial Risk, Macquarie University.

Notes

8. Brewer (Citation2007) presents a discussion on lending to small firms.

9. Studies on performance and sustainability can be found in Berrone et al. (Citation2014) and Pollinger, Outhwaite, and Cordero‐Guzmán (Citation2007).

10. MFI performance/failure/success can be measured in terms of financial sustainability, default rates, and loan‐size growth. We focus on the default risk in the analysis. See Ahlin, Lin, and Maio (Citation2011) on a broad representation of success or performance.

11. The definitions of the variables are taken from these datasets and these are presented in the Supporting Information Appendix. The descriptive statistic is presented in Appendix Table .

12. See Braverman and Guasch (Citation1986) for a detailed discussion.

References

- Ahlin, C., J. Lin, and M. Maio. (2011). “Where Does Microfinance Flourish? Microfinance Institution Performance in Macroeconomic Context,” Journal of Development Economics 95(2), 105–120.

- Baxter, M., and M. A. Kouparitsas. (2005). “Determinants of Business Cycle Comovement: A Robust Analysis,” Journal of Monetary Economics 52(1), 113–157.

- Berge, L. I. O., K. Bjorvatn, and B. Tungodden. (2015). “Human and Financial Capital for Microenterprise Development: Evidence from a Field and Lab Experiment,” Management Science 61(4), 707–722.

- Berrone, P., H. Gertel, R. Giuliodori, L. Bernard, and E. Meiners. (2014). “Determinants of Performance in Microenterprises: Preliminary Evidence from Argentina,” Journal of Small Business Management 52(3), 477–500.

- Blundell, R., and S. Bond. (1998). “Initial Conditions and Moment Restrictions in Dynamic Panel Data Models,” Journal of Econometrics 87(1), 115–143.

- Bowen, H. P., and D. De Clercq. (2007). “Institutional Context and the Allocation of Entrepreneurial Effort,” Journal of International Business Studies 39(4), 747–767.

- Braverman, A., and J. L. Guasch. (1986). “Rural Credit Markets and Institutions in Developing Countries: Lessons for Policy Analysis from Practice and Modern Theory,” World Development 14(10–11), 1253–1267.

- Brewer, E. (2007). “On Lending to Small Firms,” Journal of Small Business Management 45(1), 42–46.

- CGAP. (2003). Microfinance Consensus Guidelines. Definitions of Selected Financial Terms, Ratios and Adjustments for Microfinance, 3rd ed. Washington, DC: Consultative Group to Assist the Poorest.

- Chakravarty, S., and M. I. Pylypiv. (2015). “The Role of Subsidization and Organizational Status on Microfinance Borrower Repayment Rates,” World Development 66, 737–748.

- Christen, R. P., T. R. Lyman, and R. Rosenberg. (2003). Guiding Principles for Regulation and Supervision of Microfinance. Washington, DC: Consultative Group to Assist the Poor.

- Cull, R., A. Demirgüç‐kunt, and J. Morduch. (2007). “Financial Performance and Outreach: A Global Analysis of Leading Microbanks,” The Economic Journal 117(517), F107–F133.

- Cull, R., A. Demirgüç‐kunt, and J. Morduch. (2009). “Microfinance Meets the Market,” Journal of Economic Perspectives 23(1), 167–192.

- Cull, R., A. Demirgüç‐kunt, and J. Morduch. (2011). “Does Regulatory Supervision Curtail Microfinance Profitability and Outreach?,” World Development 39(6), 949–965.

- D'espallier, B., I. Guérin, and R. Mersland. (2011). “Women and Repayment in Microfinance: A Global Analysis,” World Development 39(5), 758–772.

- Drexler, A., G. Fischer, and A. Schoar. (2014). “Keeping It Simple: Financial Literacy and Rules of Thumb,” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 6(2), 1–31.

- Godquin, M. (2004). “Microfinance Repayment Performance in Bangladesh: How to Improve the Allocation of Loans by MFIs,” World Development 32(11), 1909–1926.

- Hartarska, V., and D. Nadolnyak. (2007). “Do Regulated Microfinance Institutions Achieve Better Sustainability and Outreach? Cross‐Country Evidence,” Applied Economics 39(10), 1207–1222.

- Hermes, N., and A. Meesters. (2011). “The Performance of Microfinance Institutions: Do Macro Conditions Matter?,” in Handbook of Microfinance. Eds. B. A. de Aghion and M. Labie. Hackensack, NJ: World Scientific, 173–201.

- Hollis, A., and A. Sweetman. (1998). “Microcredit: What Can We Learn from the Past?,” World Development 26(10), 1875–1891.

- Kaufmann, D., A. Kraay, and M. Mastruzzi. (2011). “The Worldwide Governance Indicators: Methodology and Analytical Issues,” Hague Journal on the Rule of Law 3(02), 220–246.

- Khalily, M. A. B. (1993). “The Political Economy of Rural Loan Recovery: Evidence from Bangladesh,” Savings and Development: Quarterly Review 17(1), 23–38.

- Khandker, S. R. (2005). “Microfinance and Poverty: Evidence Using Panel Data from Bangladesh,” The World Bank Economic Review 19(2), 263–286.

- Khandker, S. R., B. Khalily, and K. Khan. (1995). “Grameen Bank: Performance and Sustainability,” Discussion Paper, The World Bank, Washington, DC.

- Leamer, E. E. (1983). “Let's Take the Con Out of Econometrics,” The American Economic Review 73(1), 31–43.

- Levine, R., and D. Renelt. (1992). “A Sensitivity Analysis of Cross‐Country Growth Regressions,” The American Economic Review 82(4), 942–963.

- Patten, R. H., J. K. Rosengard, and J. R. D. E. Johnston. (2001). “Microfinance Success Amidst Macroeconomic Failure: The Experience of Bank Rakyat Indonesia during the East Asian Crisis,” World Development 29(6), 1057–1069.

- Paxton, J. A. (1996). Determinants of Successful Group Loan Repayment: An Application to Burkina Faso. Columbus, OH: The Ohio State University.

- Pollinger, J. J., J. Outhwaite, and H. Cordero‐guzmán. (2007). “The Question of Sustainability for Microfinance Institutions,” Journal of Small Business Management 45(1), 23–41.

- Reinhart, C. M., and K. S. Rogoff. (2013). “Banking Crises: An Equal Opportunity Menace,” Journal of Banking and Finance 37(11), 4557–4573.

- van Den berg, M., R. Lensink, and R. Servin. (2015). “Loan Officers' Gender and Microfinance Repayment Rates,” The Journal of Development Studies 51(9), 1241–1254.

- van Rooyen, C., R. Stewart, and T. de Wet. (2012). “The Impact of Microfinance in Sub‐Saharan Africa: A Systematic Review of the Evidence,” World Development 40(11), 2249–2262.

- Vogelgesang, U. (2003). “Microfinance in Times of Crisis: The Effects of Competition, Rising Indebtedness, and Economic Crisis on Repayment Behavior,” World Development 31(12), 2085–2114.

- Waller, G. M., and W. Woodworth. (2001). “Microcredit as a Grass‐Roots Policy for International Development,” Policy Studies Journal 29(2), 267–282.

- Wenner, M. D. (1995). “Group Credit: A Means to Improve Information Transfer and Loan Repayment Performance,” The Journal of Development Studies 32(2), 263–281.

- Zeller, M. (1998). “Determinants of Repayment Performance in Credit Groups: The Role of Program Design, Intragroup Risk Pooling, and Social Cohesion,” Economic Development and Cultural Change 46(3), 599–620.

Appendix

Table A1 Variables, Codes, and Descriptive Statistics