Abstract

This article considers a monumental architectural limestone block with altar-iconography that was found during the 2012 campaign of the Danish–German North-west Quarter project. The project, which began in 2011, has mapped the highest area within the walled city, the so-called North-west Quarter, which had hitherto remained largely unexplored. The monumental block, which was in secondary use as a late antique oil press, gives new insight into the local building traditions in Gerasa. The authors suggest that this block originally came from a building with a sacred function. Through comparison with other local sanctuaries from the region, as well as from Gerasa itself where the tradition of the horned altar-motif seems to have been flourishing in the Roman period, it is shown that this block might have belonged to a sanctuary dedicated to a deity of a local character.

Introduction

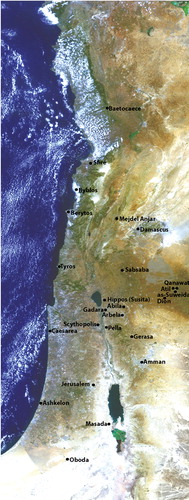

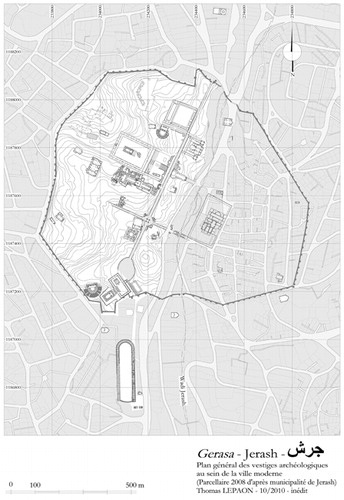

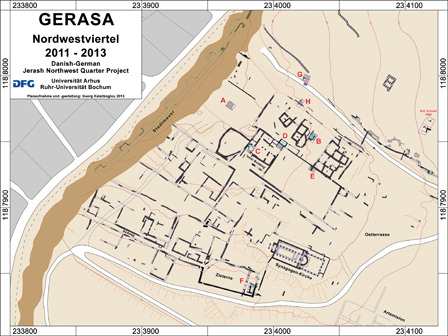

In 2011, a Danish–German archaeological project was initiated in Gerasa, a city of the Decapolis, modern Jerash in Jordan (CitationLichtenberger and Raja 2012; 2013). The project focuses on the North-west Quarter of the city. It aims to understand the settlement history of this c. 4.2 ha large area (for literature on Gerasa see most recently Andrade Citation2013, 160–69; Kennedy Citation2007; Lichtenberger Citation2003; Citation2008; March Citation2009; Raja Citation2012; Citation2013). The North-west Quarter is the highest area within the walled city and lies in the immediate vicinity of one of the monumental sanctuaries of the Roman city, namely the sanctuary of Artemis dating to the 2nd century AD () (Lichtenberger Citation2008; Parapetti Citation1980; Citation1982; Citation1989a; Citation1989b; Citation1990; Citation2002; Citation2007; Raja Citation2009). The North-west Quarter has hitherto been largely unexplored. The only excavated features were the synagogue church excavated in the 1920s and one trench on the summit, which was excavated in the 1980s (Kraeling Citation1938 for the Synagogue Church; Clark and Bowsher Citation1986 for the sounding on the summit). The Danish–German project under the direction of the authors conducted a surface survey in 2011 and documented more than 350 wall structures visible on the surface () (Lichtenberger and Raja Citation2012). In addition, geophysical prospection with geomagnetics (MAG-DRIVE) and ground penetrating radar (SIR-3000 GPR system with 270 MHz antenna) were undertaken in the entire area () (Kalaitzoglou et al. Citation2012). From this documentation, a plan was drawn in which several urban features such as building structures, streets, terraces, cisterns, caves and the physical topography are documented in detail (Lichtenberger and Raja Citation2012). Although no systematic pottery surface survey was done, it was clear that most structures visible on surface stem from the Late-Roman, Byzantine, early Islamic (c. 7th to mid-9th centuries AD) and even Middle Islamic (c. mid-9th to 15th centuries AD) periods (Lichtenberger and Raja Citation2012; Citation2014).

During the campaigns in 2012 and 2013, excavations were undertaken in eight selected areas, and further excavations are planned for 2014–16 (Kalaitzoglou et al. Citation2012; CitationLichtenberger et al. 2013 for the 2012 campaign; CitationKalaitzoglou et al. 2013; 2014 as well as CitationLichtenberger et al. 2014 for the 2013 campaign). The work is intended to clarify the settlement history of this area and its impact on the overall settlement history of Gerasa/Jerash between the Hellenistic and the Middle Islamic periods. Until now the most prominent results of the excavations are the observation that only little Hellenistic and Roman Imperial period material has come to light or was found in situ indicating that the North-west Quarter might only have been sparsely occupied during these periods. This result has a profound impact on the overall image of the development of the city in the Graeco-Roman period which, as Jacques Seigne had already postulated, might mainly have developed along the main north–south running cardo with its representative public monuments, and the space within the (later) walls might have remained largely unoccupied during the early and high imperial Roman periods (Seigne Citation1986; Citation1992). During the Hellenistic and early Roman periods, the area of the North-west Quarter was probably mainly used as a quarry site () and also seems to have had a function within the water supply system of the city, something that needs further investigation () (CitationKalaitzoglou et al. 2014; for the dating of quarry activities around Jerash, which might speak for this quarry being one of the earlier ones, see Hamarneh and Abu-Jaber Citation2013. For water supply in Jerash which is an under-researched area, see Seigne Citation2004).

Trench B and the monumental architectural block

During the 2012 campaign, one trench (trench B) was laid out on the north-eastern slope of the North-west Quarter (). The location was chosen because the area had suffered from a recent illicit excavation, which had brought to light parts of a large limestone block that seemed to be an altar with horns, a motif that is typical for Roman Gerasa ( and ) (Kalaitzoglou et al. Citation2012; Lichtenberger and Raja Citation2013). In this area, a well-constructed wall orientated north–south was already visible before excavation was undertaken. This wall turned out to be the back wall of a well-preserved and complete Late-Roman/Byzantine oil press, which was in use until around the beginning of the Early Islamic period () based on the ceramic finds in the trench (Kalaitzoglou et al. Citation2013; CitationLichtenberger et al. 2013). A later Mamluk phase, belonging to the period after the area fell out of use as an oil press, is also documented (Kalaitzoglou et al. Citation2013). Almost the complete press was uncovered including basins, the press bed and weights (). The press bed was framed by two ‘press towers’, both of which were monumental blocks in secondary use. The press is of a type that is attested in Gerasa (Brun Citation2004, 14 lever press type A3). The location of this agricultural installation within the settlement area of the walled city is worth mentioning, but is not unusual since oil presses were also installed elsewhere within the walled city (Fisher Citation1930: 9; Seigne Citation1986: 47). Furthermore, results from the 2013 excavations point to the conclusion that the north slope of the hill might have been used for agricultural purposes and organic material, including olive kernels, have been found here during excavation on the slope () (CitationKalaitzoglou et al. 2014).

Figure 6. Stretch of water pressure pipe excavated during the 2012 campaign in Trench E (Danish-German Jerash North-west Quarter Project).

Figure 7. Trench B in the northern part of the area of research before excavation (Danish-German Jerash North-west Quarter Project).

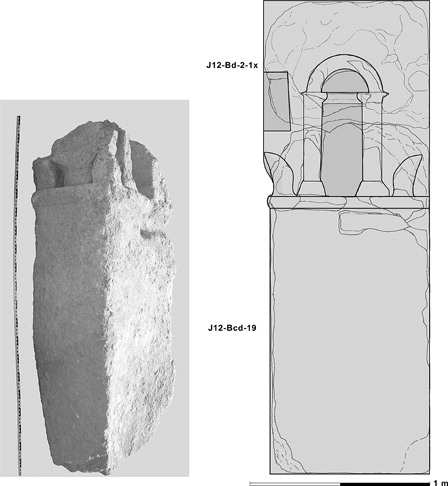

Figure 8. Photo of the monumental architectural block (Danish-German Jerash North-west Quarter Project).

Figure 11. Phase plan of Trench B with various construction phases marked in colours (Danish-German Jerash North-west Quarter Project).

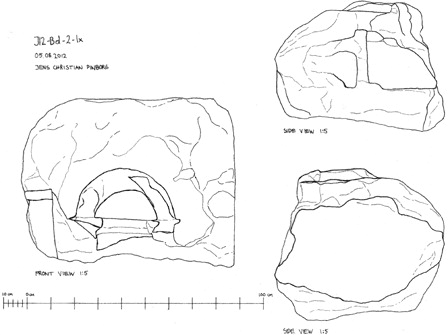

It came as a surprise that the eastern most ‘press tower’ was made from a reused monumental architectural block with altar-iconography (e.g. horns and offering bowl). The expectation had been that the block would have been a Roman period altar of a far less monumental size. A second block, which turned out to be the top part of the large block, was found during the excavation within the fill of trench B (). The total height of the architectural element would have amounted to c. 2.70 m ().

Figure 12. Close-up of organic material, pods found in Trench G (Danish-German Jerash North-west Quarter Project).

Figure 13. Drawing of the upper part of the monumental block, also found in Trench B (Danish-German Jerash North-west Quarter Project).

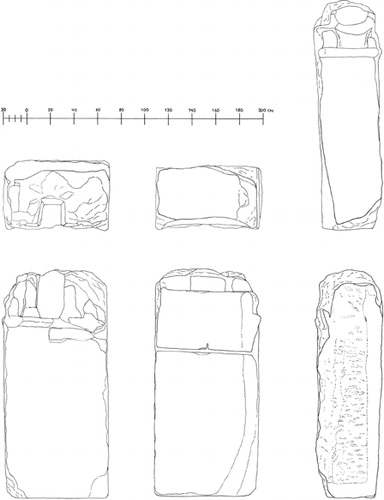

The block is a monumental, rectangular, worked block of soft whitish limestone (excavation find number: J12-Bcd-19) (). It measures 1.95 m in height, 0.89–0.90 m in width, from the lower part to the upper part, and is 0.55 m deep. The block is damaged and reworked for secondary use in the oil press in several places and the top part is broken off. Reworking for fitting the block into the oil press can be traced on the front of the block, below the pilaster columns, where a deep square hole and a depression runs horizontally from the hole to the left side of the block. The front side, up to the height of the pilasters, is curving concavely also due to the secondary use of the block as a tower in the oil press. On the rear, one-third below the top, there is a horizontal furrow, approximately 4–5 cm broad and 3 cm deep, that runs across the entire block. This has been interpreted as a late antique sawing mark. The short right side is damaged on both upper corners, and the corner horns are partly broken away.

Figure 14. Photo and reconstruction of the monumental architectural block (Danish-German Jerash North-west Quarter Project).

The block is worked on all sides. On the upper front side of the block, the lower part of two slightly off-axis columns/pilasters is preserved. The pilasters are located more to the right on the block than to the left. They are standing on a carved protruding base, which runs horizontally across the front of the entire block and continues around on the short right side of the block. Between the pilaster columns, there is a deep, narrow niche, which measures c. 23 cm (W), 41 cm (H) and 18 cm (D). Directly under the protruding basis, a centrally placed, deep, square post-hole, stemming from secondary use in the oil press, is visible. The stone curves, slightly concavely, under the protruding basis as a result of use in the oil press.

The upper corners of the short left side are each decorated with a horn, which curves slightly outwards. A deep relief shows a stylized basin or bowl (offering bowl) that appears artificially slender, due to the proportions (0.55 m) of this side of the block. The horns and the bowl are placed on the carved protruding baseline, which runs horizontally across the entire short side. Below the baseline the stone is worked but has no decorative features. The short right side is roughly smoothed and has an anathyrosis. On the upper part of the rear there is a roughly worked, horizontally running, step. As the step does not cut and damage the horns, it is not clear whether it relates to the original use of the block, or secondary reuse as an oil press. There is the already mentioned horizontal furrow on the rear; the rest of the rear is roughly worked. The top of the block is heavily damaged and weathered right across the surface. The bottom of the block is partly damaged, but has been worked in order to create a straight surface.

The top part of the monumental block was also found during excavation. It bears a niche and is made of the same soft whitish limestone as the bottom part (excavation find number: J12-Bd-2-1x). It measures 0.71 m (H), 0.89 m (W) and 0.69 m (D). The block is extensively damaged on all sides and the surface is badly weathered.

The upper part of the front side is damaged. In the centre, the curved part of a rounded niche is visible. The capitals of columns/pilasters flanking the niche on each side are also preserved. Inside the niche runs a protruding cornice. The left side of the block is also damaged and worn, and bears a carved rectangular niche. The right side, which is curving, is damaged and worn. The rear, which also is curving, is also damaged and worn. The top of the block is curving towards the rear, but is also damaged and worn. The bottom of the block shows clear signs of having been broken.

Due to the weathering of the two blocks, the two pieces cannot be joined at the fracture. However, there is no doubt that the two parts belonged together and that the smaller of the two was the top part of the larger one. This is made obvious by the corresponding measurements and the exact correspondence of the pilasters/columns, as well as the niche. It should be noted that the upper part of the front side of the block projects slightly further out than the lower part, but this projection is already starting at the lower block and continues on the upper.

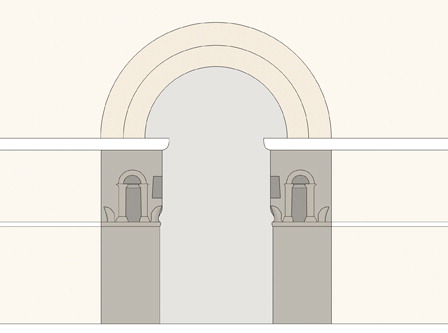

A reconstruction of the block shows that the broad front side and the short left side were meant to be seen, while the short right side (the one with the anathyrosis) was built into a wall or other structure (), as might the broad rear. At least in its present state, there is no evidence that it was meant to be seen in its original context. Integration within a wall is also a likely scenario since the whole architectural piece does not have a great depth and thus could only have constituted one face in a wall. This suggestion is supported by the fact that the left horn of the short left side, which is flat, does not project out in the manner of the right horn, which formed the corner.

Figure 15. Drawings of all sides of the monumental architectural block (Danish-German Jerash North-west Quarter Project).

The lower part of the broad front side is constructed like an altar with horns at the sides. On top of the horned altar element, however, a niche with an arched gable is positioned. Looking at the short left side, the impression of an altar is further supported, not only by the recurring horns, but also by the fire bowl/basin on top. Although this fire bowl is extremely stylized and slender, it is clear that it imitates altar-iconography as attested on the many examples of horned altars with fire bowls on top that have been found at Jerash () (Hiort Citation2013). However, on both the broad front side and the short side, the upper part of the block introduces another element, the rectangular niche, which does not belong to, or imitate, the upper part of an altar. It therefore appears that although the object looked like an altar, it was an architectural block that simply drew heavily on altar-iconography. The view that the block did not in itself function as an altar is also supported by its large dimensions and slender proportions. Nor could the fire bowl have been functional as it is cut in relief only, and simply constituted the base for the rectangular niche on top.

Figure 16. Hypothetical reconstruction of the monumental architectural block in a building (Danish-German Jerash North-west Quarter Project).

Building upon the argument that the block functioned as an architectural element that was integrated within a built structure, there are two general possibilities for its location in its original context. It could either have come from the left-hand corner of a building or an enclosure, or it could have formed the right-hand side of a framing device for a thoroughfare (doorway) or niche. Both reconstructions would have demanded at least one similar piece as pendant in order to either frame the opening or the other corner of the building.

When looking for comparanda for such an architectural element, it becomes clear that the first option – doorway or a niche – is most likely as we are not aware of instances of buildings in which such an element formed the outer corner. Thus, our suggestion is that the block belonged to an arched framing of a larger niche or a doorway (, the upper part is a hypothetical reconstruction).

Altar-iconography and niches in regional and local sacred architecture

There are two motifs, which must be considered if we seek to contextualize the architectural block. To begin with the reduction of altar-iconography to a motif of architectural decoration, we need to consider where this motif is usually found and to which kind of buildings such decoration would have been applied. Moving on to the motif of niches flanking a passageway or a larger niche, we must ask their purpose and thus consider in which kind of buildings would such decorative elements be found?

It is commonly known that in the Roman period architectural decoration sometimes took over motifs from other genres of art and decorative elements, such as decorated scrolls and friezes. Usually, the motifs, at least to some degree, correspond with the primary function of the building. In Roman art and architecture, tomb monuments, for example, sometimes apply temple or altar features with the aim of creating a sacred atmosphere (von Hesberg Citation1992: 170–201). Outside Gerasa, north of the festival theatre and pool at Birketein, the tomb of Germanus was constructed in the shape of a temple (Schumacher Citation1902: 161–65). This is an example of those temple tombs that drew upon architectural features originally belonging to other spheres, in this case sacred space. Interestingly, however, altar-iconography is absent in this grave monument as well as in other sepulchral monuments in Gerasa. Numerous funerary inscriptions were found at the site, some on altars, but the horned motif is rare on such sepulchral monuments (cf. e.g. Dalman Citation1909: 223–24, ; Jones Citation1928: 149–50, pl. XIII.8). However, such altar-iconography is well attested on other inscribed monuments in Gerasa, in the form of altar-shaped stones that have a basis and stepped profiles, and at the top are decorated with horns and a basin or bowl (Hiort Citation2013). Such monuments were often real altars, but could also sometimes have functioned as purely dedicatory monuments. In such cases, however, the dedications always referred to deities and not to people (Hiort Citation2013).

The motif depicting horns is common in the Mediterranean world (e.g. Deonna Citation1934), but it is especially well rooted in the Levant in the Late Bronze and Iron Ages (Hitchcock Citation2002; Zwickel Citation1990: 116–28, fig. 133–35). The popularity of the motif on the altars of Roman Gerasa is probably due to this tradition, which, although it cannot be proven to have been continuous, seems to have been deeply embedded in the religious culture of the region. The horn-motif seems to be a defining element of altar-iconography in this region, as can be seen in depictions of altars on coins, where the horns are prominently displayed (e.g. in the Decapolis at Abila, Spijkerman Citation1978: 54–55, no. 21 pl. 8.21 and Dion, Spijkerman Citation1978: 118–21, no. 1–3, 10 pl. 24.1–3, 10).

In the Levant, there are some architectural complexes that apply altar-iconography in their architectural decoration. However, the examples differ to some extent from the monumental architectural element found in Gerasa. Two examples are found respectively at Burj Baqirah (Steinsapir Citation2005: 50–51. 126, location not marked on ) and at close-by Khirbet el-Hatib (Kreuz Citation1999: 24–25, pl. 43–44, location not marked on ) in the north Syrian Limestone Massif (cf. also possibly an altar on the portal at Harab Sams: Tate Citation1992: 119, fig. 173). Here, small reliefs with altars frame the lintels of the entrances to the sanctuaries. In contrast to the architectural element from Gerasa, complete altars are depicted on these lintels. This is an important difference and the comparison needs to be put into further perspective, since the examples might be explained as exceptional special cases that are rooted in the local nature of the cults. At Burj Baqirah, a Zeus Bomos (Zeus Altar) was venerated. Thus, it seems self-evident that altars were depicted on the lintels as a signature of the cult. We have no information about the nature of the cult at Khirbet el-Hatib, but it might be one of a similar nature to the Zeus Bomos at Burj Baqirah, having an aniconic cult object in the form of an altar at the centre of the cult and veneration.

Another example of altar depictions framing a doorway is found at Sfire in northern Lebanon () (Steinsapir Citation2005: 70, 134–35). There, two altars, one depicted on either side of the temenos wall, frame the entrance to the sanctuary court. Within the court of the sanctuary, no temple stood, but the main focus of the cult itself was a large monumental block, a ‘monument à colonnettes’ forming the focus of the cult, which is different from typical Graeco-Roman architectural vocabulary (Kropp Citation2013: 333–34). Again in this case, as probably also in the Limestone Massif, we have a correlation between the depiction of an altar on the front, and the nature of the cult. Closer to Gerasa, in Sabsaba in the Hauran (southern Syria), a comparable doorway carrying two framing altars in relief was found (Barkay et al. Citation1974: 183, pl. 37B). The original function of the building remains unknown. In all these cases, complete altars are depicted on architectural elements. In all cases where we have some contextual information, they probably related directly to the main object of cult within the sanctuaries. Thus, they are not striking or close comparanda for the architectural block found in Gerasa. The same is true for the horned altar on the lintel relief of the en-Nusra tomb at Oboda in the Negev (Negev Citation1997: 79–88). The tomb might have belonged to priestesses (Negev Citation1997: 88) and thus the depiction of the altar and further instrumenta sacra can be explained by the social function which the deceased had in life.

Figure 18. View of the entrance to the sanctuary in Sfire with altars depicted on the entrance (after Steinsapir 2010: 134).

In some cases, altars that seem to have been used for sacrifices were integrated into door entrances. This was certainly the case for a block, used in a secondary context, and found in the Islamic baths at Hammam as-Sarakh close to Qasr Hallabat (a). The block was part of a right door jamb, at the front of which a complete altar (0.54 m (H), 0.33 m (W) and 0.31 m (D)) was protruding. This altar had horns on the top right front and left corners. The fire bowl/basin was completely functional (0.08 m (D)). This example differs from the example in Gerasa in that it functioned as an altar, however, the basic premise of altars flanking an entrance seems to be the same for the block found in Gerasa.

In the southern Hauran, small, sometimes functional, altars have been found incorporated into the entrances of houses (e.g. Butler Citation1913: ill. 193; Butler Citation1919: insc. 240 and comprehensive Dentzer-Feydy Citation2008: 202 ill. 128–132b).

There are some monuments with more ambiguous iconography and it is conceivable that they also applied iconography alluding to altar-motifs in their architectural decoration. In the temenos architecture of the citadel of Amman, the walls were decorated with monumental blocks carrying aediculae decorated with shell motifs (Northedge Citation1992: figs 30–34 for hypothetical plan of the Roman temenos and sanctuaries, as well as drawings of the niches, which interestingly are shown without the small ‘horns’ here. Compare with in order to see the ‘horns’). These aediculae were flanked by small ‘horns’ (). The blocks were once most likely part of the inner façades of the temenos wall of one of the large sanctuaries, as suggested by Northedge (Northedge Citation1992: figs 30–34), and which have not yet with certainty been ascribed to any deity (for possible attribution to Heracles, cf. Lichtenberger Citation2003: 275). In the early Islamic period, they were reused in the extensive Umayyad palace on the citadel, but have not previously been studied in greater detail in order to understand the architectural elements in their original contexts (Northedge Citation1992 treats the citadel in the Islamic periods, but also refers to the reused spolia from the Roman period monuments). There is, however, an important difference between the niche elements from the citadel in Amman and the block in Gerasa. The ‘horns’ attached to the niches incorporated into the temenos wall in Amman are the only elements, which can be related to altar-iconography. A basin or bowl is entirely missing. Thus we may also consider an alternative interpretation for the Amman elements, namely that what look like ‘horns’ might be acroteria used to give the niches the shape of proper three-dimensional aediculae with architectural decoration and not with features intentionally alluding to altar-iconography.

The altar-iconography on the architectural block in Gerasa thus finds little comparison, and the few pieces discussed here (some of them, however, being quite different from the block in question) hint at an original use of the block in a sacred or sanctuary context. Assuming that the block was part of an entrance or framed built architecture, we must look to the other important motif on the block, namely the niche on the front.

Small niches are a very common feature in Roman architecture. They are used extensively in the architecture of Gerasa, e.g. rows of niches still stand along the cardo, incorporated into the proscaenia of the theatres and built into the outer cella walls of the temple of Zeus Olympios. The function of such niches is usually impossible to determine and they could probably have served various purposes such as holding statues, statuettes, votives or simply have been left empty serving a purely decorative purpose in themselves.

However, we may in fact be able to categorize these niches in a bit more detail by establishing where they were located in the sanctuaries (in general for the motif cf. Freyberger Citation1999: 133–34; Citation2004: 19, n. 17, ; Kader Citation1996: 161–62, fig. 77). There are various, frequent occurrences of such niches. (1) niches flanking the entrance of a temenos, (2) niches flanking the entrance to a naos, the temple building itself and (3) niches flanking the back wall of the adyton (the inner) or cella of the temple. For all categories numerous monuments can be listed, but we restrict ourselves here to a few examples only. Of course niches are a widespread feature in Roman architecture and per se not characteristic enough for a semantic interpretation. The syntax of such niches in architectural compositions, framing an entrance or the cultic focus, can however, be contextualized within sacred architecture.

(1) Niches flanking the entrance of a temenos

Often niches flank entrances and evoke a kind of baroque visual language at façades. The monumental Artemision in Gerasa is a striking and local example of the use of niches to flank a sanctuary entrance: the propylaia of the Artemision, when entering from the cardo, are framed by two large niches (). In fact, two lateral niches are often found at the entrances of sanctuaries all over the Roman Near East. These include among others Baetocaece (), (Hösn Suleiman) (Freyberger Citation2004; Krencker and Zschietzschmann Citation1938: 104, figs 1–3, pls 48–49) and Sfire in Lebanon () (Aliquot Citation2009: 237–42; Krencker and Zschietzschmann Citation1938: 20–34, pl. 12–18; Nordiguian Citation2005; Taylor Citation1986) where such features form prominent parts of the façade of the sanctuary. Niches framing an entrance to a sanctuary are thus common features in Roman period sacred architecture in the Near East.

(2) Niches flanking the entrance to a naos (the temple building itself)

Niches flanking the entrance to the naos/temple also seem to be very common. In the Hauran, for example, such examples are plentiful. We find this layout at as-Suweida (Brünnow and Domaszewski Citation1909: 95) and at Atil (Brünnow and Domaszewski Citation1909: 103) as well as at Sur al-Ledja (location not marked on ). In Upper Galilee, such niches are attested at the temple of Kedesh (Fischer et al. Citation1984: 152–53). These naoi could be standing within an architecturally visible temenos, as well as standing without any noticeable framing. This means that there does not seem to have been a pattern in whether or not niches were only incorporated into the façade of the temple, if the temple was not standing in an architecturally defined temenos.

A subtype of (2) is niches inside the entrance, facing it, as in the prostylos of Qanawat (Brünnow and Domaszewski Citation1909: 134). Exactly the same motif recurs on the monumental architectural block from Gerasa above the fire basin on the short side.

(3) Niches flanking the back wall of the adyton (the inner) or the cella of the temple

Another application of niches in sacred architecture is niches placed either, within the adyton of the temple, or on cella walls separating the adyton from the rest of the interior of the temple. Such niches are also found frequently in sanctuary architecture of the Roman period in the Near East. In Mejdel Anjar in Lebanon, niches are incorporated both on the cella walls, as well as in the adyton (Krencker and Zschietzschmann Citation1938: fig. 76). In Qanawat in the Hauran, niches flank the adyton of the prostylos (Brünnow and Domaszewski Citation1909: 134). Further east, in Palmyra, in the temple of Bel, such niches are attested in the North adyton (Browning Citation1979: 121; location not marked on ), and in the adyton and the cella of the temple of Baal-Shamin in Palmyra such niches also occur (Collart and Vicari Citation1969: 155). In the countryside of Palmyra, the temple at Khirbet Ouadi Souâné has niches in the adyton (Schlumberger Citation1951: 33–34, fig. 14; location not marked on ).

Tying these applications of niches together with other evidence from the broader region, it becomes clear that the niche motif as well as the horn-motif were both used regularly in sanctuary contexts. As niches are also well attested in other contexts, the altar-motifs are the crucial ones for interpretation. However, there is also important evidence from Kedesh in Upper Galilee, where the cultic function of two lateral niches at the front of the naos can be further determined (Fischer et al. Citation1984: 152–53). There installations for libations were found, pouring liquids from the front into the naos. Although these installations are thus far from unique, they underline the point that cultic activity took place at such niches flanking the entrance to a sanctuary. A practical ritual function is also suggested by the altar-block from Hammam as-Sarakh, which, likewise, flanked an entrance (to an unknown building) (a). Its deep fire basin indicates that it was used for offerings.

Based on the comparanda brought forward here, although these are not exhaustive, there is little doubt that the architectural monumental block found in Gerasa came from a built structure with a sacred function. It has been shown that the horned altar-motif was not closely related to grave-architecture. This supports the interpretation that the block stems from a building with a sacred function. It is presently impossible to determine whether the block framed the entrance to a temenos, the entrance to a naos itself, or a cella or adyton.

The date of the block

The comparanda for the motifs of the block indicate that it has to be dated to the Hellenistic–Roman period. As it is not inscribed, there is no evidence, which allows us to date the block more precisely. Stylistically, the block does not allow for firmer dating. Its overall eclectic and exceptional composition makes it impossible to classify it chronologically. Furthermore, the single architectural motifs (niches, horns, basin) are in their typological development too unspecific in order to be dated precisely.

From its raw material, the characteristic soft whitish limestone, one could argue that the block did not stem from the Trajanic-Hadrianic building programme of Gerasa, which was mainly executed in harder, reddish limestone (see below). However, this observation does not help to narrow the date range, since this kind of limestone was used in periods both before and after. Nor does the date of the construction of the oil press provide us with conclusive evidence for the dating of the block. The oil press was probably constructed in the 3rd/4th century AD. If the block belonged to the first phase of the press, it can be assumed that the original context of the block had been dismantled by that point. This, however, still prevents a precise dating of the block.

The origin of the architectural element in Gerasa

The architectural block was found in secondary use in an oil press. Thus, its original location and the location of the presumed sanctuary are hard to establish. In principle, the block could have come from anywhere in the city. However, there are some observations that must be taken into account and that might be put forward in order to strengthen the thesis that the block originally came from the North-west Quarter. The monumental dimensions of the stone might suggest that it was not brought from afar to be used within the oil press. It would not have been convenient to move it from far away to what was the highest area within the walled city lying on a steeply sloping hill. This argument, however, is not conclusive, since large stones may, of course, have been moved over larger distances.

The material of the block provides us with further circumstantial evidence for the question of the origin of the architecture in which the block had primarily been used. The major urban expansion that took place in Gerasa from the times of Trajan and Hadrian onwards, and which mainly clustered along the cardo, included many representative public buildings and monuments. For most of them, a harder reddish limestone was preferred (cf. Seigne and Morin Citation1995: 179). Thus, it is probable that the block did not belong to this 2nd/3rd century AD building programme that took place in the city centre, but rather stemmed from either an earlier building and/or from a building on the periphery of the settlement.

From the syntax of the block, it is clear that it employed Graeco-Roman architectural features, but that in its eclecticism it does not belong to canonical Graeco-Roman architecture. Moreover, from the comparanda discussed here, which used altar-iconography in architectural decoration, it is clear that we are dealing with sanctuaries with strong links to traditions. Thus, it can be argued that the block belonged to the sanctuary of a cult that in its architectural expression drew on local features.

From an abundance of inscriptions and other sources, we know of many deities in Gerasa (Lichtenberger Citation2003: 191–243; Riedl Citation2005: 147–225). The evidence comes from across the city and important centres are the temple of Zeus Olympios in the south and the temple of Artemis in the central northern part of the city. In the area south of the Artemision, a cluster of cults and sanctuaries can be traced, none of which seem to be Graeco-Roman at their core and which might, therefore, have used architecture such as the monumental block presented here. In this area, local deities were worshipped. These were to some extent Hellenized but kept strong local characteristics. The so-called Temple C is such a sanctuary, with architectural features hinting at concepts of Syrian and Mesopotamian architecture (Fisher and Kraeling Citation1938; Lichtenberger Citation2003: 238–41). Inscriptions tell us about the cult of a local deity Pakeidas/Theos Arabikos (Welles Citation1938: 383–86, nos 17–22) who might have been worshipped in the temple under the cathedral (Lichtenberger Citation2003: 221–25). Last but not least, Artemis herself has to be mentioned. It is plausible that she was a Hellenized local female deity that by means of an interpretatio Graeca became an Artemis. Thus, in this area adjacent to the North-west Quarter of Gerasa, several sanctuaries were located, which were strongly rooted within the local religious culture and it is plausible that the block from the North-west Quarter belonged to such a sanctuary.

There is not enough substantive evidence to go further and attribute the block to one specific sanctuary. It is tempting to consider whether it came from an earlier temple of Artemis. When the large temple of Artemis was built during the reign of the emperor Hadrian, massive terracing took place and covered all possible earlier structures. From coins and inscriptions, we know, however, that there must have been a temple of Artemis at least from the 1st century AD (Spijkerman Citation1978: 158–59, no. 3; Welles Citation1938: 388–90, nos 27–29). It is a matter of dispute whether it stood in the same location as the later Artemis sanctuary or somewhere else. If it was in the area of the later Artemision, such a building could be a possible candidate for the origin of the architectural block from the North-west Quarter. However, as there were many other deities venerated in Gerasa, this conclusion has to remain hypothetical.

Conclusion

An architectural element, which was found in secondary use in an oil press in the North-west Quarter of Gerasa, provides us with important insight into the architecture of sanctuaries in Gerasa. It is evidence for architectural expressions going beyond the large 2nd- and 3rd-century AD Graeco-Roman buildings along the cardo, since it in its eclecticism displays features that adopted Graeco-Roman architectural expressions, combined them and turned them into something new, yet un-canonical. The architectural block is further evidence for the degree of architectural variation and innovation within the urban fabric of Roman Gerasa, an important city in the Graeco-Roman Near East.

References

- Aliquot, J. 2009. La Vie Religieuse au Liban sous l'Empire Romain. Beirut: Institut français du Proche-Orient.

- Andrade, N. J. 2013. Syrian Identity in the Graeco-Roman World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Barkay, G., Ilan, Z., Kloner, A., Mazar, A. and Urman, D. 1974. Archaeological survey in the Northern Bashan (preliminary report). Israel Exploration Journal 24: 173–84.

- Browning, I. 1979. Palmyra. London: Chatto and Windus.

- Brünnow, R. E. and von Domaszewski, A. 1909. Die Provincia Arabia. Auf Grund zweier in den Jahren 1897 und 1898 unternommenen Reisen und der Berichte früherer Reisender, III. Straßburg: Trübner.

- Brun, J.-P. 2004. Archéologie du Vin et de l'Huile de la Préhistoire à l’Époque Hellénistique. Paris: Éd. Errance.

- Butler, H. C. 1913. Publications of the Princeton University Archaeological Expeditions to Syria in 1904–1905 and 1909. Division II Section A3. Architecture in Syria, Southern Syria, Umm idj-Djimal. Leiden: Brill.

- Butler, H. C. 1919. Publications of the Princeton University Archaeological Expeditions to Syria in 1904–1905 and 1909. Division II Section A. Architecture. Southern Syria. Leyden: Brill.

- Clark, V. A. and Bowsher, J. 1986. A note on soundings in the Northwestern Quarter of Jerash. In, Zayadine, F. (ed.), Jerash Archaeological Project 1981–1983, I: 343–49. Amman: Department of Antiquities of Jordan.

- Collart, P. and Vicari, J. 1969. Le Sanctuaire de Baalshamin a Palmyre, I. Topographie et Architecture. Neuchatel: Institut Suisse de Rome.

- Dalman, G. 1909. Einige Inschriften aus Dscherasch. Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins 32: 222–25.

- Dentzer-Feydy, J. 2008. Le décor architectural des maisons de Batanée. In, Clauss-Balty, P. (ed.), Hauran, 3. L'habitat dans les campagnes de Syrie di Sud aux époques classique et médievale: 183–231. Beirut: Institut français du Proche-Orient.

- Deonna, W. 1934. Mobilier délien. Bulletin de Correspondance Hellenique 58: 381–447.

- Fischer, M., Ovadiah, A. and Roll, I. 1984. The Roman Temple at Kedesh, Upper Galilee: a preliminary study. Tel Aviv 11: 146–72.

- Fisher, C. S. 1930. Yale University–Jerusalem School Expedition at Jerash: first campaign. Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 40: 2–11.

- Fisher, C. S. and Kraeling, C. H. 1938. Temple C. In, Kraeling, C. H. (ed.), Gerasa. City of the Decapolis: 139–48. New Haven: American Schools of Oriental Research.

- Freyberger, K. S. 1999. Das kaiserzeitliche Damaskus: schauplatz lokaler tradition und auswärtiger einflüsse. Damaszener Mitteilungen 11: 123–38.

- Freyberger, K. S. 2004. Das Heiligtum in Hössn Soleiman (Baitokaike): religion und handel im syrischen küstengebiet in hellenistischer und römischer zeit. Damaszener Mitteilungen 14: 13–40.

- Hamarneh, C. and Abu-Jaber, N. 2013. Documentation and protection of the Quarries of Gerasa. Levant 45(1): 57–68.

- Hiort, D. M. D. 2013. The Roman Horned Altar: An Analysis, Discussion and Contextualisation of the Material from Jerash. MA: Aarhus University.

- Hitchcock, L. A. 2002. Levantine horned altars: an Aegean perspective on the transformation of socio-religious reproduction. In, Gunn, D. M. and McNutt, P. M. (eds), ‘Imagining’ Biblical Worlds. Studies in Spatial, Social and Historical Constructs in Honor of James W. Flanagan: 233–49. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press.

- Jones, A. H. M. 1928. Inscriptions from Jerash. Journal of Roman Studies 18: 144–78.

- Kader, J. 1996. Propylon und Bogentor. Damaszener Forschungen 7. Mainz: Zabern.

- Kalaitzoglou, G., Knieß, R., Lichtenberger, A., Pilz, D. and Raja, R. 2012. Report on the geophysical prospection of the Northwest Quarter of Gerasa/Jerash 2011. Annual of the Department of Antiquities of Jordan 56: 79–90.

- Kalaitzoglou, G., Lichtenberger, A. and Raja, R. 2013. Preliminary report of the second season of the Danish–German Jerash Northwest Quarter project 2012. Annual of the Department of Antiquities of Jordan 57: in press.

- Kalaitzoglou, G., Lichtenberger, A. and Raja, R. 2014. Preliminary report of the third season of the Danish–German Jerash Northwest Quarter project 2013. Annual of the Department of Antiquities of Jordan 58: in press.

- Kennedy, D. 2007. Gerasa and the Decapolis. A ‘Virtual Island’ in Northwest Jordan. London: Duckworth.

- Kraeling, C. H. (ed.) 1938. Gerasa. City of the Decapolis. New Haven: American Schools of Oriental Research.

- Krencker, D. and Zschietzschmann, W. 1938. Römische Tempel in Syrien. Berlin: de Gruyter.

- Kreuz, P.-A. 1999. Kaiserzeitliche Heiligtümer im nordsyrischen Kalksteinmassiv. MA: University of Cologne.

- Kropp, A. J. M. 2013. Images and Monuments of Near Eastern Dynasts, 100 BC–AD 100. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Lichtenberger, A. 2003. Kulte und Kultur der Dekapolis: Untersuchungen zu Numismatischen, Archäologischen und Epigraphischen Zeugnissen. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

- Lichtenberger, A. 2008. Artemis and Zeus Olympios in Roman Gerasa and Seleucid religious policy. In, Kaizer, T. (ed.), The Variety of Local Religious Life in the Near East in the Hellenistic and Roman Periods: 133–53. Leiden: Brill.

- Lichtenberger, A. and Raja, R. 2012. Preliminary report of the first season of the Danish–German Jerash Northwest Quarter project 2011. Annual of the Department of Antiquities of Jordan 56: 231–39.

- Lichtenberger, A. and Raja, R. 2013. Schicht für Schicht in die Vergangenheit. Welt und Umwelt der Bibel. Archäologie, Kunst, Geschichte, 18: 62–63.

- Lichtenberger, A. and Raja, R. 2014. Towards an understanding of the Dark Ages of Islamic Jerash. Connecting the evidence through texts and archaeology. Comparative Islamic Studies (in press).

- Lichtenberger, A., Raja, R. and Sørensen, A. H. 2013. Preliminary registration report of the second season of the Danish–German Jerash Northwest Quarter project 2012. Annual of the Department of Antiquities of Jordan 57 (in press).

- Lichtenberger, A., Raja, R. and Sørensen, A. H. 2014. Preliminary registration report of the third season of the Danish–German Jerash Northwest Quarter project 2013. Annual of the Department of Antiquities of Jordan 58 (in press).

- March, C. 2009. Spatial and Religious Transformations in the Late Antique Polis. A Multidisciplinary Analysis with a Case-study of the City of Gerasa. Oxford: Archaeopress.

- Negev, A. 1997. The Architecture of Oboda. Final Report. Qedem 36. Jerusalem: Institute of Archaeology.

- Nordiguian, L. 2005. Temples de l’Époque Romaine au Liban. Beirut: Presses de l'Universite Saint-Joseph.

- Northedge, A. 1992. Studies on Roman and Islamic ‘Amman. Volume 1: History, Site and Architecture. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Parapetti, R. 1980. The Sanctuary of Artemis at Jerash. Annual of the Department of Antiquities of Jordan 24: 145–50.

- Parapetti, R. 1982. The architectural significance of the sanctuary of Artemis at Gerasa. Studies in the History and Archaeology of Jordan I: 255–66.

- Parapetti, R. 1989a. Scavi e restauri Italiani nel Santuario di Artemide 1984–1987. Syria 66: 1–39.

- Parapetti, R. 1989b. Jerash – The Sanctuary of Artemis. In, Homès-Fredericq, I. D. and Hennessy, J. B. (eds), Archaeology of Jordan II. Field Reports, vol. I, Field Reports, Surveys and Sites (A–K) (Akkadica Supplementum VII): 323–29. Leuven: Peeters.

- Parapetti, R. 1990. La Sanctuaire d'Artemis rival du Temple de Zeus. Le Monde de Bible 62: 28–30.

- Parapetti, R. 2002. Gerasa und das Artemis-Heiligtum. In, Hoffmann, A. and Kerner, S. (eds), Gadara — Gerasa und die Dekapolis: 23–35. Mainz: Zabern.

- Parapetti, R. 2007. Il santuario di Artemide a Jerash. Osservazioni topografiche. In, Di Vita, A., Faccenna, D., Giuliano, A. and Invernizzi, A. (eds), Giornata lincea in ricordo di Giorgio Gullini: 71–80. Rome: Bardi.

- Raja, R. 2009. The Sanctuary of Artemis in Gerasa. In, Fischer-Hansen, T. and Poulsen, B. (eds), From Artemis to Diana. The Goddess of Man and Beast, Acta Hyperborea 12: 383–401. Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press.

- Raja, R. 2012. Urban Development and Regional Identity in the Eastern Roman Provinces, 50 BC–AD 250: Aphrodisias, Ephesos, Athens, Gerasa. Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press.

- Raja, R. 2013. Changing spaces and shifting attitudes. Revisiting the sanctuary of Zeus in Gerasa. In, Kaizer, T., Leone, A. and Thomas, E. (eds), Cities and Gods. Religious Space in Transition: 31–43. Leuven: Peeters.

- Riedl, N. 2005. Gottheiten und Kulte in der Dekapolis. PhD. Freie University Berlin <http://www.diss.fu-berlin.de/diss/receive/FUDISS_thesis_000000001712>.

- Schlumberger, D. 1951. La Palmyrène du Nord-ouest. Villages et Lieux de Culte de l’Époque Impériale. Recherches Archéologiques sur la mise en valeur d'une Région du Désert par les Palmyréniens. Paris: Geuthner.

- Schumacher, G. 1902. Dscherasch. Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins 25: 109–77.

- Seigne, J. 1986. Recherches sur le sanctuaire de Zeus a Jérash (Octobre 1982–Décembre 1983), rapport préliminaire. In, Zayadine, F. (ed.), Jerash Archaeological Project 1981–1983, I: 29–59. Amman: Department of Antiquities of Jordan.

- Seigne, J. 1992. Jérash romaine et byzantine: développement urbain d'une ville provinciale orientale. Studies in the History and Archaeology of Jordan IV: 331–56.

- Seigne, J. 2004. Remarques préliminaires à une etude de l'eau dans la Gerasa antique. In, Bienert, H. D. and Häser, J. (eds), Men of Dikes and Canals. The Archaeology of Water in the Middle East: 173–85. Rahden: Marie Leidorf.

- Seigne, J. and Morin, T. 1995. Preliminary report on a mausoleum at the turn of the BC/AD century at Jarash. Annual of the Department of Antiquities of Jordan 39: 175–91.

- Spijkerman, A. 1978. The Coins of the Decapolis and Provincia Arabia. Jerusalem: Studium Biblicum Franciscanum.

- Steinsapir, A. I. 2005. Rural Sanctuaries in Roman Syria: The Creation of a Sacred Landscape. BAR International Series 1431. Oxford: Hedges.

- Tate, G. 1992. Les Campagnes de la Syrie du Nord du IIe au VIIe Siècle. Paris: Geuthner.

- Taylor, G. 1986. The Roman Temples of Lebanon. A Pictorial Guide. Beirut: Dar el-Machreq Publishers.

- von Hesberg, H. 1992. Römische Grabbauten. Munich: Beck.

- Welles, C. B. 1938. The inscriptions. In, Kraeling, C. H. (ed.), Gerasa. City of the Decapolis: 355–494. New Haven: American Schools of Oriental Research.

- Zwickel, W. 1990. Räucherkult und Räuchergeräte. Exegetische und Archäologische Studien zum Räucheropfer im Alten Testament. Freiburg: Universitätsverlag.