Abstract

The Society for Folk Life Studies was founded in 1961 and since 1963 has published its journal Folk Life. This article outlines the origins of the Society and analyses its work and membership over the past fifty years. This is followed by reminiscences and observations on the purpose and activities of the Society by a number of its long-term members. Two appendices list the senior officers of the Society and the locations of its annual conferences since 1961.

The idea to create the Society for Folk Life Studies (SFLS) was discussed at a meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science in Cardiff in 1960. An inaugural meeting in London founded the Society in September 1961, its first annual conference took place at Reading in September 1962, and the publication of the first volume of its journal, Folk Life, took place in November 1963. With the publication of the second part of volume 50 of Folk Life in the middle of 2012, it seems an apt moment to consider briefly the origins, development and achievements of the Society. As befits an organization whose main activities have centred on producing a journal and holding annual conferences for its very dedicated members, the Society’s first half-century can be usefully considered through its origins, members, publications, and the conference locations they visited.

It may be unusual to preface a celebratory article with a criticism, but in attempting to compile this brief account of the SFLS it seems that the most serious failure by its members has been their inability to maintain an archive of the Society’s business. This has meant that in particular the administrative history of the SFLS can, at present, be only sketched from other sources. In this the Society is not alone of course, as many heritage organizations ironically seem particularly reluctant to preserve the evidence of their own histories. With this caveat in mind, what follows is an account based upon information culled from the Society’s journal, newsletter, and other publications, as well as personal reminiscences and observations solicited in 2011 and early 2012 from a number of members of long standing.Citation1

The establishment in 1961 of a society in the UK and Ireland to promote folk life studies had a considerable period of gestation. Generally, in the two decades after the Second World War there developed two contrasting cultural spirits: modernism and the neo-vernacular. In many ways, the latter followed from a rejection of the former, with a growing interest in and desire to record the rural and vernacular cultures that were being subsumed quickly by industrialization, urbanism, and the modernist tone of post-war reconstruction. More specifically, the Society came into being through the determined efforts of a small group of eminent museum curators and academics in Great Britain and the Republic of Ireland that included Iorwerth Peate, Estyn Evans, G. B. Thompson, and Caoimhín Ó Danachair, Alexander Fenton, and Stewart Sanderson. The central figure in this group was Iorwerth Peate (1901–82, ), who had joined the National Museum of Wales in 1927 and was appointed the first Keeper of Folk Life in 1936. Peate popularized the idea of a Welsh Folk Museum, and when this was established at St Fagans, near Cardiff, in 1948 (now St Fagans, National History Museum) he was appointed its first Curator. During the inter-war period Peate and his associates were in close contact with a wide group of European ethnologists, especially in Scandinavia. They were also active in both the Royal Anthropological Institute and the Anthropological Section (Section ‘H’) of the British Association. Peate and his colleagues used these two organizations to help define what folk life studies meant in the context of the British Isles and to generate support to establish a society dedicated to this subject.Citation2

Figure 1. Iorwerth Peate making a presentation at the SFLS annual conference held in Northern Ireland during September 1966.

Following a symposium on the scope and methods of folk life research, which took place in Edinburgh during September 1959, it was agreed to hold a meeting during the following year’s British Association annual conference in Cardiff, where the plan to establish a society for folk life studies could be mooted. This meeting took place on 1 September 1960 and a steering committee was then established to convene the inaugural conference in 1961 in London, when the Council of the Society could be elected. This took place in September and Peate was elected the Society’s first President.Citation3

Since at least 1953 Peate had been pressing the academic community to establish a journal for UK and Irish folk life studies, and in the middle of 1956 he began publishing his own journal. Entitled Gwerin, A Half Yearly Journal of Folk Life, it was a privately-funded publication whose content and format Folk Life would later follow quite closely. The only real difference was that Peate used his editorship of the independent Gwerin to speak out strongly against an assortment of issues that he saw as threatening to Welsh folk culture including the closure of railways, afforestation, and the creation of reservoirs. Although constantly short of funds, Gwerin ran for six years, concluding with its fourteenth issue in December 1962, deliberately linking with the delayed publication of the first volume of Folk Life in the middle of 1963.Citation4

With the establishment of the SFLS annual conferences in September and the publication of Folk Life each summer, the format of the Society’s activities was set by the mid-1960s and has remained largely the same ever since. In 1973, Folk Life acquired the subtitle, ‘A Journal of Ethnological Studies’, along with a major redesign. The subtitle had been agreed at the annual conference in Glasgow in 1972 after considerable debate. It seems the more academic members (following recent European developments) had argued for abandoning the use of the term ‘folk life’ completely in favour of ‘ethnology’, but other members (including Peate) opposed this. The compromise resulted in the addition of the subtitle to the original title of the journal.Citation5 The only other change to date took place in 2010 when Folk Life began to be published in two parts each year.

The members have been extremely loyal in their support of the Society, with many remaining affiliated for several decades. After an initial surge in the early 1960s, when around 700 people and organizations had joined, the average number of members has been around 400, approximately half of which were institutions ().Citation6 Unusually for many organizations (and to its great credit), the Society has always drawn its members from all parts of the British Isles, including the Irish Republic and Northern Ireland, and the contributions to the work of the SFLS from members based throughout Ireland have been very considerable. During the last two decades, membership beyond the British Isles has increased and in 2004 the annual conference was held in mainland Europe for the first time. The recent publication of Folk Life online has broadened the profile of the Society to a global level, and it will be interesting to see if in the next decade this digital presence can also help increase further the active participation by international members and supporters at the annual conferences and other meetings.

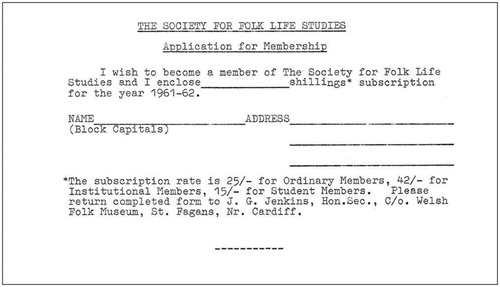

Figure 2. Original application form for membership of the Society for Folk Life Studies, which was circulated in the December 1961 issue of Gwerin.

The Society has always been strongly supported by museum curators, but it has also included members from a wide range of other professions, private collectors, and interested laypeople. Although this ‘broad church’ spirit is still very much alive within the Society today, it was during its first decade that the Society was particularly popular amongst academics, especially within the subjects of geography and anthropology, archaeology, history, and language studies. By the 1970s, however, a good number of members from these disciplines moved on to engage with more specialist groups for such things as vernacular architecture, post-mediaeval archaeology, and landscape studies.Citation7

A greater loss came in the early 1980s when the Group for Regional Studies in Museums (a group established in 1974 by members of the SFLS) transformed itself into the Social History Curators Group (SHCG). This reformed group actively sought to distance itself from the SFLS by concentrating on more contemporary, urban, and industrial heritage, and at times eschewing material cultural studies in favour of dynamic forms of community engagement as the main purpose of curatorship. This vibrant group soon attracted many of the upcoming curators in the new and revitalized history museums that were developing throughout the UK. As a result, the largest professional constituency within the SFLS lost much curatorial new blood and the opportunity to embrace further more urban and contemporary subjects. Today, the interests and concerns of both organizations are more similar, but the culture of belonging to only one of the groups still persists.Citation8

The most recent attempt to assess the occupations of the membership and their motivations to join the SFLS took place during the spring and summer of 2000 when the Society undertook a brief attitude survey of its personal members. Around forty per cent responded and endorsed the work of the Society wholeheartedly.Citation9 Members were drawn from a wide range of professions, although museum curators and academics featured large. Many also belonged to a number of related organizations in the British Isles and internationally. Research into a vast array of subjects was being actively pursued. The Society’s interdisciplinary concerns and membership were widely appreciated and the quality, range, and usefulness of the journal were universally acclaimed. The annual conference was liked for both the opportunity it presented to learn about an area and to network informally in the friendly, out-of-session gatherings.

As with any small society, the officers of the SFLS have consistently played a key role in not only maintaining good governance, but also setting the agendas and overall tone of the organization. A list of the holders of the key posts within the Society is given in Appendix 1. The range of institutions in which these people worked clearly shows that museum curators have always led the organization and that there has always been broad support for the Society throughout the British Isles. In the same vein, the office of President has moved steadily around members from Ireland, Wales, Scotland, and England. Indeed, the original constitutional rule of a Presidency lasting for five years was changed in the mid-1970s for a term of three years because it was realized that otherwise it would take too long before senior members of the Society from every country could hold this office.Citation10

From at least 1980 the Society has kept a tradition of Presidents giving an address to the annual conference that concludes their three-year term of office. These provide a useful insight into the various interests and concerns of many of the leading members of the Society and how they viewed its current state and future prospects. In 1980, Trefor Owen attempted to galvanize the Society into thinking in more depth about folk life studies as an academic discipline, while also sketching some of the recent European debates about the discipline.Citation11 In 1986 Geraint Jenkins spoke passionately in favour of the human history approach to museum interpretation and voiced concern about the rising heritage industry with its bland interpretation centres. He also was highly critical of the more arcane studies in material culture found in the pages of journals such as Folk Life!Citation12 In 1989, Alan Gailey investigated how culture was an important aspect of folk life studies, explored how and why culture migrates and looked at some of the consequences of this migration. He also provided a very useful model for the ethnological study of migrant cultures.Citation13 In 1992, Brian Loughbrough discussed folk life interpretation in museums and elegantly warned that this needed to take account of popular, political, and economic concerns while maintaining academic rigour. He provided an astute SWOT analysis of the Society that is still applicable today.Citation14 In 1995, Ross Noble pondered the meaning of ‘traditional’ in our urban, post-industrial society, integrated with European culture and with ethnically diverse communities. He urged that the Society could and should respond to these changes and in fact had an important interpretative role to play.Citation15 In 2002, Catherine Wilson argued the very convincing case for dynamic partnerships to be developed between rural life museums and private collectors and enthusiast groups to preserve, restore, and interpret agricultural hardware.Citation16 The theme of collecting and interpreting rural life was picked up again in 2008 by Roy Brigden, when he discussed how existing collections within museums can be re-interpreted in a number of ways as society and rural culture changes. He also outlined two methods of active collecting to record recent rural life. The first, by recording contemporary craftspeople as an update to earlier records of work practices. The second, by actively collecting a targeted body of artefacts that could demonstrate not only the practical, but the social and cultural aspects of change in rural society.Citation17

Many of the office-holders listed in Appendix 1 held posts of considerable responsibility in some of the leading institutions within the British Isles. Given the busy professional lives of these people, it is a testimony to their dedication to the Society that they often served as officers for a considerable number of years — decades in the case of all the Editors, and several Secretaries, Treasurers, and Conference Secretaries. The tenure of these positions has also had the less obvious impact upon the SFLS by constantly renewing the membership, as many current members reminisce that it was their director or line manager who first suggested they join the Society and then ‘encouraged’ them to take an office or assist with organizing a conference.

During the Society’s first half-century roughly four ‘professional generations’ can be identified amongst the active membership. The earliest was made up of people such as Peate, who were already well advanced in their careers when the Society was formed. Their immediate juniors and assistants (such as Jenkins and Owen) rapidly took over the running of the SFLS and very much set its tone and operational systems from the late 1960s to the late 1980s. A third generation (such as Stevens, Eveleigh, and Roberts) then started moving into senior positions within the Society. Over the past few years yet another group of younger professionals has started to become active in managing the SFLS. Sadly, over the last decade or so, increasingly restricted budgets (in museums in particular) have reduced greatly the opportunities to introduce younger members in this way, and since the current global financial crisis began this situation has become much more acute. Today the Society is still in search of other ways by which a new generation of members can be recruited.

The journal, Folk Life, has been central to the work and very existence of the SFLS and this publication has greatly benefited from the long service of each of its editors. Following the failure of the first Editor to produce a journal in the two years after the founding of the Society, the inimitable J. Geraint Jenkins took over the post and successfully produced annual volumes from 1963 to 1979, followed by his colleague at the Welsh Folk Museum, William Linnard, who oversaw the journal until 1991.Citation18 Roy Brigden of the Museum of English Rural Life then took over until 2002, when the current Editor, Linda Ballard of National Museums Northern Ireland, succeeded him.

Between 1963 and 1972 a ‘Notes and Comments’ section of Folk Life provided the members of the young society with information about upcoming meetings and brief lists of the speakers at the annual conferences. This section was omitted when the journal was redesigned in 1973. In 1986, the Secretary, Peter Brears, instituted an annual Folk Life Newsletter. This was originally produced on the photocopier at St Fagans, but since David Eveleigh’s editorship it has been printed professionally and has steadily developed into the sizeable, full-colour publication it is today. As well as providing members of the Society with information on forthcoming events and notices of publications, it provides a useful summary of the excursions and papers given at the previous year’s annual conference, including the minutes of the annual general meeting.

An online presence for the Society began in 2001 when it established a modest website, developed by Beth Thomas at St Fagans. By early 2003 the text of the newsletter was being made available on this site along with an index to Folk Life. An even greater digital development took place in 2009, when Folk Life was published online for the first time for institutional subscribers (with individuals and smaller museums receiving the journal in hard copy). From the following year two numbers of each volume were published annually. Online publication is considerably increasing the global reach and impact of the journal, and as a result in 2011 the decision was taken to digitize all the back numbers of Folk Life and make them available online from 2012. This development is bound to raise the profile of the Society further and hopefully elicit even more wide-ranging articles for publication.

Elsewhere in this edition of Folk Life, Linda Ballard has written very perceptively about the many contributors to the journal, and it is testimony both to her and the preceding three editors that the high standard of this publication has been maintained throughout the last fifty years.Citation19 At no period can the journal be said to have ‘dipped’ in quality of content or relevance, nor has the regularity of its publication faltered. Since 2002 the journal has benefited from a formalized peer-review process overseen by an international editorial board, and from 2005 Cozette Griffin-Kremer has acted as the journal’s Reviews Editor (a role previously held during the 1990s by David Eveleigh). As a result of these innovations Folk Life has expanded its international coverage and become increasingly officially recognized as a journal in which publication can be counted within the academic credit system.

Today, Folk Life continues to be a highly respected and widely read journal and this consistent quality has not been won at the expense of a dull uniformity in content. Over 420 articles and shorter notices have been published since 1963 and a brief analysis of these reveals several trends. The broad range of expertise often brought to bear within many of the journal’s articles makes an exact classification of content difficult, but this exercise has been influenced by the groupings discussed by Bill Linnard in 1980 and by some recent personal observations of Alan Gailey.Citation20 By reducing the nine subject areas Linnard identified to five groups (1 – theory, museology, and sources; 2 – agriculture; 3 – settlements, buildings, and communities; 4 – crafts, tools, costume, and textiles; 5 – belief, custom, language, and food) and adding a sixth category for the small number of miscellaneous papers published, it is possible to gain a good overview of the balance of articles both overall, and during each editorial period. Taking the 49 volumes of Folk Life as a whole, the largest portion (31 per cent) of the 425 papers analysed relate to belief, custom, language, and food, with the other four main subject categories being fairly balanced at between 15 to 18 per cent each. The miscellaneous group accounted for only four per cent of the total. However, when these categories are analysed by decade from 1963, a number of variations and trends can be seen. The percentage of articles on crafts and so on remains unchanged throughout the five decades, but during the same period there is a steady increase in the articles dealing with theory and museology (9 per cent to 23 per cent). For the other three main subject groups, the decade 1983–92 witnessed the greatest variation, with a shrinkage to seven per cent of articles on settlements, buildings, and communities, along with some expansion of the percentages for agriculture (to 25 per cent) and belief, custom, language, and food (to 36 per cent). In the following two decades, however, the number of papers on agricultural subjects fell sharply (to between 11 and 13 per cent). This seems to reflect the decline in interest in rural life museums that the Society has worked so tirelessly to change.

These variations reflect, in part, a number of trends within the museum and heritage sector where, until very recently, there has been a steady growth in the number and complexity of history museums and a growing desire to improve standards of curatorial practice. The paucity of articles on settlements, buildings, and communities during the 1980s is probably a legacy of a number of experts in these fields becoming less involved in the SFLS in favour of other, more specialist organizations. These variations in content will also have been influenced to some degree by the contacts and interests of the four editors and, before he died in 1982, Iorweth Peate. Given J. Geraint Jenkins’ work at the Welsh Folk Museum as assistant to Peate’s deputy, Ffransis Payne, it is not surprising that virtually 60 per cent of all articles under Jenkins’ editorship were concerned with belief and custom, and settlements, buildings, and communities.Citation21

The growth of global media and e-communication from the mid-2000s can be identified as factors for the changes in geographical coverage by articles in Folk Life. During Jenkins’ time only around six per cent of all papers dealt with subjects outside the British Isles. The two succeeding editorial periods saw this percentage increase to around ten per cent, while under Linda Ballard this figure rose again to 22 per cent. Another cause of this may be due to a decline in articles from UK institutions, as in most history museums today there are few opportunities (or indeed great encouragement) for academic research and publication in material culture.

When Iorwerth Peate reached his sixty-fifth birthday in 1966 and retired as President of the Society, a festschrift was planned to mark the occasion, containing articles by a number of the leading members of the Society. It was hoped that such a volume would also begin a series of publications by the Society that could compensate for the small quantity of literature on the subject in the UK. Probably because of a shortage of funds, this book was not published until 1969 under the title Studies in Folk Life and was financed by a long list of personal and institutional subscribers.Citation22 It is an impressive collection of essays, ranging in subject from linguistics to agrarian history, and in geography from Orkney to Menorca, but, despite this, no further attempt has yet been made by the Society to publish monographs or collections of essays in addition to its journal. However, the Society has been a key mover and shaker for a number of heritage organizations that have then developed their own institutional structures and publications. The two most high profile of these have been the Group for Regional Studies in Museums and the Rural Life Museums Action Group.

As mentioned above, the Group for Regional Studies in Museums (GRSM) was established in October 1974 by two leading members of the SFLS, Geraint Jenkins and Peter Brears. Initially the Group aimed to provide in-service training for history curators, as Peter Brears recalls:

Up to this time all social history curators studying for the Museums Association Diploma had to undertake a residential curatorial course led by practicing professionals, most of whom were established members of the SFLS. As the Museums Association had decided that specialist curatorial knowledge was now unnecessary and cancelled these courses, there would now be no means of providing young curators with the required degree of expertise or contact with others working in this field. GRSM was therefore set up to fulfil these needs. There was much discussion as to its title; the ‘Regional Studies’ element being strongly proposed by the academics, as departments of regional studies were now being established in a number of universities. The decision to follow this advice was, in retrospect, counter-productive, since it did not represent the aims of the Group, which was largely museum-based. The name had to be changed to Social History Curators Group some years later.

More generally, GRSM can be seen as a response to the growth of social and local history as subjects in their own right, which were being drawn upon to help create a large number of new museums, especially in urban areas. The Group was very successful in providing a point of contact for this rising number of history curators, where they could develop and share good practice in promoting regional studies within their institutions. Soon GRSM was also seeking to establish a clear identity for history curatorship and gain for it equal status with other museum disciplines. This campaigning spirit changed the agenda for the group and by the end of 1982 members decided to re-name the organization the Social History Curators Group. By then, such had been the influx of new members with no affiliation to the SFLS that an account of the Folk Life annual conference in SHCG News of late 1982 had to be prefaced by a description of the aims and objectives of the Society. Sadly, the crossover in membership between the two societies has been small ever since, but the SFLS can pride itself on bringing into being such a dynamic curatorial organization that has had a major impact on history museums for the last quarter of a century.Citation23

The Rural Life Museum Action Group (RuLMAG) was set up in 2001 under the aegis of the SFLS with the aim of progressing the recommendations of the Museums and Galleries Commission’s report, Farming, Countryside and Museums (2000). Many members of the action group were also members of the Society, and the vast practical and academic knowledge and experience of rural life in museums present within the SFLS has proved to be of great benefit to the work of RuLMAG. The action group evolved into the Rural Museums Network (RMN) in 2005 and this is now formally constituted as a charitable trust. Over the past decade the Network has acted as an important forum for re-thinking the role of rural life museums, coordinating collection surveys, and sharing good practice in displays, learning programmes, and governance in these institutions. The relationship between the Society and the Network is still very close, with many joint members. Indeed, the Society’s annual conference of 2010 included a consultation session on the impact of the Network that fed into Hilary McGowan’s report, Rural Museums: Ten Years On (2011).Citation24

The Society’s annual conference is central to the social dynamic of the SFLS in a number of ways. Given the widespread distribution of its supporters, the opportunity to gather in one place for three or so days each year provides the only real occasion for the active members of the Society to meet one another. The informality and conviviality of the conferences is remembered by many members as a key feature of these gatherings, not just for the enjoyment they provide, but because they enable experienced and newer professionals to meet on an equal basis.

A list of the locations of all the annual conferences held between 1961 and 2011 is provided in Appendix 2. This shows how the Society’s members have visited each country and virtually every distinct area of the British Isles. Of the 51 meetings, 21 (40 per cent) have taken place in England, and eight (16 per cent) each in Ireland, Scotland, and Wales. For the remaining 12 per cent of conferences, the Isle of Man has been visited three times, and Cornwall Jersey and Brittany once each.Citation25

This peripatetic policy has not only given the members insights into the diversity of traditional cultures, but also allowed the widely-located membership closer access to the conference every few years. During the Society’s first ten or so years, the location of the conference seems to have been determined by the twin aims of visiting each country, as well as learning about the leading folk museums and academic institutions within the British Isles. Another element of variety has been provided by the informal tradition of holding the conference in a location closely associated with the President, towards the end of his or her term of office.

Although the days of the week in which the conferences take place have slightly altered, the overall format of the events has remained remarkably consistent through the last fifty years. A good number of papers are balanced by excursions around the conference location, often with opportunities to meet local craftspeople or watch demonstrations of traditional skills. Also, some form of local musical entertainment or performance is usually included. Peter Brears recalls that in the early conferences this was provided by the members themselves; ‘featuring the wonderful storytelling of Caoimhín Ó Danachair and the songs of Paddy MacMonagle, along with many other memorable performers’. The conferences have almost always been able to welcome visiting academics or curators from mainland Europe and North America, as well as provide a platform for short contributions from members about current work in progress or smaller projects, including presentations from recipients of the annually-awarded student bursary.

In addition to the annual conference, the Society aims to hold at least one study day each year. Often, these have taken the form either of visits to significant collections or archives or joint meetings organized by other organizations. The Society’s widely distributed membership has tended to consider these meetings difficult to support in large numbers, but the consequentially small gatherings are often more memorable because of the in-depth discussions that arise and are possible in these situations.Citation26

Looking back over the first half-century of the Society, it is clear that it has achieved much. Through its journal and its annual conferences, the SFLS has both stimulated and advanced the study of folk life within and beyond the British Isles. Furthermore, the Society has remained very consistent in its approach to ethnology, welcoming a wide range of specialist knowledge and fostering interdisciplinary studies wherever possible. For much of its existence Folk Life has been regarded as the leading journal for this area of study. Unlike many learned organizations, the membership of the SFLS has not been prone to disputes over ideology or new trends in thinking. Indeed, the great sociability of its gatherings has been frequently cited as one of the most attractive features of the Society. However, perhaps this easy-going, all-encompassing spirit of the Society can also be considered as a weakness, as it has sometimes fostered a perceived lack of subjective focus and intellectual thrust amongst those outside the organization. It is clear that the Society is held in high regard and great affection by its supporters and that personal endorsement (particularly through work colleagues) has been the strongest incentive to join. Although the journal is acknowledged as the key intellectual driver in the Society, for many people the opportunities for professional development and networking provided by the annual conferences are acknowledged as the most enduring aspect of membership.

It seems very fitting for a society so focused on human interaction and agency, that the thoughts of its members should underpin this short discussion of the first fifty years of the SFLS. During the 2011 conference I chaired a group discussion with delegates on the progress, successes, and future of the Society.Citation27 The positive, personal views expressed during this session not only helped frame the structure of this article but also suggested that it would be useful to record the reminiscences and observations of some of the long-term members of the Society. Following this conference, a number of these members were approached for their thoughts on why they joined the SFLS, what they considered were its greatest achievements, and what they felt about the current state and future prospects of the Society. Extracts from their replies are reproduced here, grouped under five headings. Looking to the future, these stalwarts remain positive and optimistically inventive despite the changing culture within the museum and heritage profession that now seems to threaten the usual methods of the Society’s succession planning. It is very heartening that the SFLS can face the uncertainties of the next half-century with such high morale.

Joining the Society

I joined SFLS when it was set up because I already then had developed an interest in folk life as a subject. […] I was appointed to the newly created Ulster Folk Museum in late 1960, so it followed almost as a matter of course that I joined SFLS. Although I joined in 1962, it was only in 1964 that I was able to attend an annual conference. AG

As I recall it, I joined the SFLS at an early stage. When I moved to Lincoln after some six years at Reading, I needed a link to what I regarded as my geographical and social/economic history background. The society provided it, and when later the GRSM left the path of regional studies to concentrate on social history I was glad that SFLS remained true to its origins and continued to regard the whole of northwest Europe as appropriate territory and continued its peripatetic conferences. BL

It was Bríd Mahon of what became the Department of Irish Folklore in University College Dublin, who introduced me to Folk Life Society conferences. I really had no idea of what to expect but just imagine my mixture of awe and delight when, as a raw postgraduate who had just submitted her MA, I found myself, next to Venetia Newall whose work I so much admired, mutually appreciating a cooper at work in Ennis, County Clare (1978). Bríd really enjoyed meeting colleagues at those conferences and appreciated the value of contacts in her world of costume and food research and kindly made sure to introduce me. FCW

Best recruiter for Folk Life — probably — was Eileen Fellowes, who was Geraint’s [Jenkins] secretary back in the ’70s. She was a member of longstanding and had been a regular attender at conference in the early days (and at British Association meetings, from which Folk Life grew). No one spent any time at St Fagans without being given a Folk Life membership leaflet by Eileen. This is how I came to join in 1974/5, and I was also given (as an incentive, I guess) some early back numbers by the then editor, JGJ [Geraint Jenkins] himself. CS

At the time [that I joined just after starting St Fagans in 1973], SFLS was THE central society in that side of museum work and it was a very broad field because it included a lot of subjects like vernacular architecture, crafts, farming, folklore, etc., etc. […], synoptic, shall we say? A lot of the people there were specialists in their individual disciplines, and I’m thinking particularly of vernacular architecture, but they still saw it as part of a greater whole. And it is to all our detriments that groups like that have gone their separate ways and become inward looking and don’t see the relevance and the linkages between their subject with everybody else’s subject. JWD

I joined the Society in 1980 about two years after taking up post at the Museum of English Rural Life at the University of Reading. It was at the time, I recollect, part of a conscious effort to widen my network of my contacts although it was a few years before I became actively involved in Society affairs, attending my first conference at Sheffield in 1987. Through attending several conferences over the years I have met many people some of whom have become good friends. For me the wide range of people the Society has brought together has been one of its great strengths. The Society has always been more than a club of museum curators and the knowledge and enthusiasm of members from outside the profession has been one of its great strengths — people like Paddy MacMonagle and the late Kate Mason, to name just two. DE

My first conference was at Wrexham in 1980 where I met many great characters — and was conned, and not for the first time, into doing a job on Council — being what was then called Assistant Treasurer (later Membership Secretary); Rosie Allan was finding it too much work with so much going on at Beamish at the time, and I was approached by the usual cabal which included Geraint Jenkins and Brian Loughbrough. I was much too young and innocent to realize I was being press-ganged, and was very flattered and agreed. Rosie passed on the old card index, which still exists, and many of the cards are still written in her hand. CS

I first encountered SFLS when I joined J. Geraint Jenkins for my first job working at the Welsh Folk Museum. Here I found a larger-than-life President of the Society (and Editor of its journal) and a team of young researchers all of whom made folk life studies relevant to my explorations into the potential of tourism in rural areas. TS

I can’t remember exactly when I joined the Society in my own right — as opposed to being part of a member institution — but it must have been the late 1970s/early ’80s. The reason I became an active member of the Society and started attending the annual conference was because it was the prime means of meeting and spending off-duty time with senior representatives from the principal museums of traditional culture across the UK and Ireland. They would all be there every year, like the gathering of an exclusive little club, and there was no other comparable forum. At the same time, one of the most enjoyable and refreshing aspects of the Society has always been that it is not exclusively about museums and museum people but rather draws together a range of individuals from a variety of backgrounds, walks of life and enthusiasms. That’s what has given the Society so much colour and vibrancy over the years, particularly at the annual conferences. RB

I was told that I should become a member of the Society for Folk Life Studies by my line manager, J. Geraint Jenkins. That meant there was no escape! I had, though, become aware of the Society and its work when I took up my first post at St Fagans in late 1980. On moving, within a year or so, to the National Slate Museum at Llanberis, with Geraint in overall charge, other societies initially seemed to be more relevant, particularly those with a focus on the history of industry and industrial communities. I had enjoyed being a member of Llafur (the Welsh Labour History Society) at that time, participating in conferences and day schools — and my perception of the Society for Folk Life Studies was that it might have comparatively little appeal. DR

As I recall, my own involvement as a personal member of the Society, and thereafter as a reasonably active one, dates only from the late 1990s with my emergence from twenty-eight years’ local government service into a freelance life, and thereby a much greater involvement in collections around the whole of the UK. As representative of an institutional member before that, my preoccupations were not dissimilar but focused principally on the Northleach collection and its development. Membership of the Society gave me that wonderful range of contacts which I think we all regard as a core value of SFLS. It also provided understanding about how others in the membership had trodden this same path before me with their own collection responsibilities. Even with the much-welcomed development of special interest groups (encouraged by the Special Subject Network initiative nationally) these links remain valuable. DV

I have been a member of the Society for Folk Life Studies for over ten years now, since the meeting in Jersey in 2000 and have reaped countless benefits from membership, not least of them the pleasure of working as Reviews Editor with Linda Ballard, Editor of Folk Life. My background is in Celtic Studies, mainly calendar studies, and the history of techniques, especially agriculture and food production, so it might be only ‘natural’ that I would gravitate toward the SFLS, as I had used articles from Folk Life in preparing my doctorate and French DEA (pre-doctorate in the low-tech studies). As part of the work on pre-industrial dairy production for the DEA here at Centre d’Histoire des Techniques at the Conservatoire National des Arts et Métiers, I was happily packed off in 1992 for an internship at Sain Ffagan, where I worked directly under Minwel Tibbott, whose work I had read, of course. She — and her husband, Delwyn — made me feel welcome at work and outside and was, to my mind, an epitome of the authors who contributed, in all their diversity, to Folk Life over the years, with her rather eclectic interests, relaxed way of working hard, and easy-going efficiency in interviewing people. Of course, I met John Williams-Davies at the same time and T. Alun Davies, as well as other people who mentioned, in passing, their connection with the Society. The actual impetus to come to the Jersey meeting arose from my role in the international relations of the AFMA (Federation of Agricultural and Rural Life Museums in France) and I have tried to keep up the links, if at times tenuous, since then. At present, SFLS member Duncan Dornan is hosting a meeting to help relaunch the AIMA (International Association of Agricultural Museums), so the work of joining others fruitfully carries on. CGK

Publications: appreciating the journal Folk Life

A good journal was essential in the early days, and I remember the meticulous care that the late Margaret Fuller gave to the cover of the new Folk Life. Early success came from attracting contributors with established reputations. I think of Anne Buck’s piece, ‘Dress as a Social Record’, for example. BL

An early decision for me was to acquire a complete set of journals (which Roy Brigden kindly facilitated) and this has remained a source of guidance and inspiration on my shelves ever since. With my own particular research interests in traditional farm wagons and carts across the UK (and the voluntary and continuing compilation of a National Register), I have found very useful, informative and stimulating some of the articles in early issues of Folk Life, especially those by the late Geraint Jenkins, author of The English Farm Wagon (1961) and doyen of wagon studies, not only in England but across the UK as well. Such material culture studies, essentially object-related, remain the bread and butter of what Folk Life — and therefore SLFS — for me is all about, and I hope my own modest contributions have added something useful into the mix. DV

The various editors [of Folk Life] down the years have done a wonderful job of getting material for the journals […] getting balanced content. You could argue that the Society’s greatest contribution has been the journal, because it has resulted in extremely important articles being published, subjects seeing the light of day that would not otherwise have been [published]. Because in the early years the specialist journals that would have published those articles […] just did not exist. To publish a run of journals of that consistent quality for fifty years is remarkable. And to do that for a society that does not have a ‘captive audience’ (it is not like a dentists’ journal for dentists, it’s a generalists’ journal for generalists in a way) makes it even more a remarkable achievement. JWD

I was continually amazed, during my time as editor of the journal, at the quality and breadth of the articles offered. They might be meticulous object- and document-based studies — one on skillets comes to mind — or more sociological and contemporary essays such as one I recall on the late twentieth-century phenomenon of the car-boot fair. Archaeology, folklore, food history, linguistics, social history, local history, industrial history, costume history: the journal is nothing if not eclectic. In truth, this is a weakness as much as a strength because the difficulties of satisfactorily defining the boundaries of folklife or ethnology in the British context have left it struggling for an identity. It can almost be said that the Society is not subject-based, but rather a coming together of individuals who rejoice in their rich diversity of expertise and interests. RB

Places and people: the annual conferences

Although I did not become a member immediately upon joining MERL, I helped to organize what I believe was the first residential conference based in Reading with accommodation provided at Wantage Hall. I recall Andrew Jewell seeking to mollify a rather grumpy Iowerth Peate, who was unhappy with the quarters assigned to him and his wife in one of the hall houses. Being in charge of the bar provided at Wantage Hall was an introduction to the prodigious capacity of members attending the annual conference, where they were inclined to help themselves (the net profit of 6d. was regarded as satisfactory). BL

Certainly it was considered a huge honour to be invited to attend the Folk Life conference. You really had arrived when you were given admission to the ‘inner circle’. JWD

Joining the Society for Folk Life Studies was a rite of passage, and so too those early conferences in Douglas (1969), Dublin (1970), Glasgow (1972), Cardiff (1974), and elsewhere. Steeped in the spirit of the Scandinavian pioneers, this was the era of the early folklife ‘greats’ and their slightly younger colleagues: Iowerth Peate, Trevor Owen, and Geraint Jenkins; Tony Lucas, Caoimhín Ó Danachair, George Thompson, and Alan Gailey; Frank Atkinson, Anne Buck, and Venetia Newall; Stewart [Sanderson], Sandy [Fenton], and the Megaws — Basil and Eleanor. Also the likes of Brendan Adams; Kate Mason (a remarkable storehouse of Yorkshire farming tradition delivered with a strong dose of straight talking); Geoffrey Dent (egg-collecting at Bempton, Folk Life, 18); the Killarney cohort; and such younger contemporaries as Tim O’Neill and Rosie Allan. Not all were academics or curators; some younger participants moved off into other careers; others hung on (not least the indefatigable Brian Loughbrough and quietly-spoken Alan Pearsall); and many were simply fascinated by the subject-matter. This too was the time of liberally-laced late-night discussions in someone’s conference room. JB

The first SFLS conference held in Leeds in 1963 was organized by Stuart Sanderson. Due to the popularity of the TV programme ‘The Good Old Days’, Sanderson organized a conference visit to the programme’s location, the Leeds City Varieties theatre. Outside of TV broadcasts this was a notorious strip show venue, and the delegates sat through such a show. Peate was there with his wife and made no comment, but the quantity of smoke coming from his pipe increased during the performance! PB

I believe my first conference was in Liverpool in 1971. From the first I was amazed by the wide-ranging backgrounds, interests, and depths of knowledge of the people who had gathered there. These were scholars who had studied ethnology in European universities or who already had a lifetime of fieldwork and publications behind them. There was no dry, pedantic scholarship here, however, just enormous experience and wisdom deceptively masked beneath heavy layers of good-natured enthusiasm, story-telling and often alcohol (though never to excess). One was immediately put at ease, rapidly developing combinations of real friendship and real respect, which have lasted for decades. In every way the SFLS has successfully performed its primary role in bringing together all manner of people interested in its diverse subjects to their mutual benefit. PB

The conferences always attract the stalwarts, but also the local archivists and activists in whatever location the conference finds itself. We all have, I’m sure, highlights that we like to recall: mine include Brian Loughborough’s pioneering exhibition of the artefacts of people from various places who had made their home in Nottingham (Nottingham, 1992), the fascinating sound of that Bible reading in Lake District dialect (Ambleside, 1988), the magical walk through the lantern-lit wood to the bonfire for a singsong with the Copper family at the Museum of Rural Life Sussex (Chichester, 1994), the gleaming silver in Cutlers’ Hall (Sheffield, 1978), and the wonderful display of maps and documents spread out for us by the archivist in the record office (Bangor, 1986). We went on that evening to visit a vessel moored in the harbour. Unfortunately it was low tide, making it a very long descent down a vertical ladder to the deck. I am happy to recall that, to his wife Anne and everyone else’s relief, Kevin ‘Nothing Daunted’ Danaher [Caoimhín Ó Danachair] successfully managed the manoeuvre. Throughout his declining years Anne bravely managed to shepherd Kevin to conferences and we continued to benefit from his knowledge. Even then little escaped his notice: I clearly recall his query at Bunratty Folk Park, ‘What’s a Clare chair doing in a Limerick house?’ FCW

Thinking of the variety of locations reminds me of the crofts at Trotternish on Skye and our former Editor, Bill Linnard, disappearing into a ferocious rainstorm below the Cuillins. BL

Conferences have loosened us from our specializations and offered us privileged glimpses into hidden worlds through visits to preserved workplaces like coal mines and slate mountains (Bangor 1986) and talks such as Tom Sheedy’s on river poaching or Geoffrey Dent’s on gamekeepers’ calling instruments. A noteworthy feature of conferences in the past was to include a speaker from outside of England, Ireland, Scotland, or Wales. I particularly recall a Swedish colleague speaking on place-names at sea in a fishing community and a Polish colleague on the many uses of birch. Valuable and memorable, too, have been the short members’ papers, whether ranging beyond these shores like Sandy Fenton on Hungarian bread ovens, or Philla Davis on straw work or, like Peter Brears on food, Bruce Walker on vernacular architecture (accompanied by his bold, distinctive sketches), and Sheila Cass on needlework, sticking closer to home. And remember all the armchair travelling that we did with Alan Pearsall? Long may the Society’s conferences continue to bring people together. FCW

I cannot remember the exact year in which I joined the Society for Folk Life Studies. However, I know that my main interest would have been in the articles on folk drama in our journal, this being my principal area of work in folklore. I am much clearer when it comes to remembering my first conference, that was Cardiff in 1998. I had never been a great conference goer; I had attended a handful of the Folklore Society conferences in the thirty years I had been a member and I cannot recollect having attended any meeting of the English Folk Dance and Song Society despite my long membership. But Cardiff attracted me for a number of reasons. First, I had spent eight years as a coalminer and a folk conference with coal mining as one of its themes appealed to me. Secondly, the keynote speaker was Dr Bill Jones; he and I had corresponded about an article I had published in Llafur on the English language poems of Robert Jones Derfel, a Welsh bard who had lived in Manchester. As I set off for the conference, I couldn’t help wondering to what extent I would really enjoy the weekend, after all, I didn’t expect to know anybody. I discovered however that as soon as I approached the registration table I was warmly welcomed by Christine Stevens and Mared Sutherland, as she was then. Before the first evening in the bar was over I found that I knew Dafydd [Roberts], Catherine [Wilson], and Paddy [MacMonagle], all of whom I was to learn were important figures in the society, but none the less, ready to welcome a newcomer. My wife was similarly affected as she attended later conferences in Jersey and Brittany. Hence when Seb [Littlewood] was looking for new members at Killarney, Sheila was an easy catch: ‘They are all such nice people’, she told me. EC

The member’s paper I gave — almost by accident —was in Scotland [Kittochside, 2001]. I remember looking at the booking form and thinking that the old method of picking cider apples ceased to exist on my farm the previous autumn. It should not, I felt, like so much of agriculture, disappear when those who remember die — or should it? After giving a member’s paper on this (a frightening experience!) my scribble grew into a little book, which finally saw the light of day about five years ago, with a mention of the Society in the back. Without the persuasion and help of a number of members, several no longer with us, my paper would not have been enlarged into a booklet. GB

Perhaps the most memorable of conferences came early in my career when I was invited to accompany Geraint Jenkins as President to the conference in Kingussie in the Highlands of Scotland (1985). We took what was then the oil workers’ flight to Inverness. Booze flowed on the flight and arriving at Inverness Airport JGJ asked why there was a red carpet, a brass band, and the Mayor waiting. They were there to greet a famous President! Geraint was given a royal welcome to the Highlands. That was the status and stature of the SFLS thirty years ago. Would the same happen today? TS

My first experience of SFLS and its members was at the Truro (1984) conference. As it happened, this conference did in fact enable me to indulge my interest in industrial history, during an excursion to see some former copper mining sites. Geraint Jenkins was President at the time and, at some point over the weekend, shared with me the news that I would be responsible for organizing the Bangor (1986) conference. There was truly no escaping now. Looking back over almost thirty years, it appears to me that I’m still not very much wiser as to what the Society’s aims and objectives really are. The programme which I assembled for the 1986 Conference, under Geraint’s semi-detached tutelage, would have sufficed for a historical society which had a wide range of people-related interests. DR

I joined the Society in 1985 or 1986. The first conference which I attended was the 1988 Ambleside one. Two things which I remember from this event are a lengthy recitation of local dialect poems, most of which I failed to understand, and, more positively, a journey to the Stott Park Bobbin Mill. After squeezing down narrow roads we enjoyed being shown around by men who had worked at the mill before it had been taken over and preserved by English Heritage. In 1999 we visited London, when I organized a conference based at Imperial College. Dafydd Roberts, our long-serving Conference Secretary, and I had previously visited a University of Westminster campus, and thought we had booked there, but they decided they couldn’t accommodate us on the dates we wanted. Then I thought I’d found accommodation in Southwark, but that also fell through, so eventually we ended up at Imperial College. Unfortunately the conference did not attract as many participants as we’d hoped, one group decided to use a local hotel rather than student accommodation, and some people stayed with friends and relations in London, so we were unable to fill all the rooms we had booked, and, although I think the conference was enjoyed, it almost bankrupted the Society. The next conference I attended was the Norwich one in 1996. I remember this mainly for the outstanding introduction to the Norfolk Broads on the first evening. We have usually been provided with excellent introductions to the areas in which we met, but, for me, the overview we received in Norwich was the best of the lot. Various people who are no longer with us are remembered from these conferences. For me, perhaps the most notable was Anne Buck, always elegant and young-at-heart, approachable, and usually surrounded by a number of much younger female acolytes, most of whom went on to occupy important positions within the Society. RV

I have no detailed recollection of joining the Society, but it seemed a natural thing to do when I was appointed to the Welsh Folk Museum in 1971, and I guess it was expected. Iorwerth Peate had only retired a year previously, and Geraint Jenkins was Editor. It was certainly expected that one attended conference regularly and presented papers, and certainly Geraint was always keen to maintain a proper Welsh representation in the journal. Up to half-a-dozen from WFM would attend in those days. As the years passed and funding became tighter, one could only attend meetings if one was a committee member or presenting a paper, or otherwise involved. EW

Virtually all the curatorial staff [of St Fagans] […] had attended the conference at some time or another. They all knew the other people in their field from other organizations, so it was a very strong network. I suppose the number of people working in the field was fewer then. JWD

The annual conference has always been at the core of the Society and I have enjoyed many. They have introduced me to the warmth and hospitality to be found across these islands and shown me the meaning and the value of local culture. The conferences are like the Society itself — a little bit eccentric, learned, quirky, prim and drunken all at once. In the memory, they are always bathed in the warm glow of late summer, apart from that time we battled with horizontal rain to make our way round some of the historic sites on Skye. Two instances I won’t forget: Paddy [MacMonagle] with his erudite and hilarious talk on Irish poteen backed up with copious samples to taste, and standing in the spectacular hillside setting of Llanbryn-Mair churchyard listening to the story of Iorwerth Peate, whose village this was, and glimpsing his inspiration for a museum of the Welsh people. RB

In common with many traditional academic societies SFLS has had to learn the benefits of the internet and live with the bridge from older style publications to the new. Contributions have become more immediate and there is scope for work in progress. BL

The Society’s impact

[The greatest achievement of the SFLS has been to provide] an outlet for scholarly research in the field of folk life studies, in the absence of any other society that was directly concerned with the same subject. The problem of the Society all along [has been] that it has a base largely in museums and similar bodies, but its need is really in the academic field; to establish scholarly work in that field. […] There always is the necessity to have a base within the university where the subject is passed on […] to a new generation. That’s one thing that I think the museum isn’t so well placed to do. TO

It is clear that SFLS’ initial achievement, and I believe its greatest, lay in providing a forum for folk life as a subject, not just as an interdisciplinary meeting place. The early membership was drawn from a variety of backgrounds: academia — geography and anthropology, archaeology, history, languages, and place names; museum staff, who were a minority in the membership; and unattached, knowledgeable, and committed individuals. It needs to be recalled that local history did not yet exist, and social history barely existed in universities in the early 1960s. AG

[Iorwerth Peate viewed the theoretical aspects of folk life studies] as an adjunct to museums […] He wasn’t so keen on the university aspects of it. St Fagans was his world, in a way, and university work was outside that world. He made a good contribution [to knowledge] of course, a useful contribution, but for him the museum was the be-all and end-all. TO

When [Iorwerth Peate] saw something he went at it to study and do it, and when he wrote a review or an article he had no problem getting pen on paper. I think his problem might have been looking again at what he had written and revising it or even preparing it in an unfinished version for completion later on. […] [If] he saw something he had the vision […] and then that vision was put on paper or acted on [but] he never went beyond that. I don’t think he thought again about some of the points that he made. It wasn’t part of his mental make-up. He moved on. TO

Peate was very dismissive of the new title of [Folk Life] as a journal of ethnological studies […] oh he didn’t approve of that at all […] Peate’s view of folk life was very popular and populist. I don’t think he approved of it becoming an academic discipline in the formal sense that way that [the title] Ethnology would suggest. He saw it as free to roam across any number of disciplines. JWD

The Society has helped to publicize a number of splendid newer museums within the Britannic Isles, among whose number we should remember, the country museum at Muckross House, Killarney, the National Museum of Rural Life, at Kittochside, the Ulster Folk and Transport Museum, the museums of the Isle of Man, and the National Museum of Wales. These museums have also pioneered the preservation and interpretation of rural dwellings and even landscapes. BL

One of the successes of the Society has been the international dimension: both with the attendance at conferences of colleagues from the rest of Europe and beyond, and also publication of their articles. BL

I am by nature a creature of the city and so extensive collections of tractors and combine harvesters leave me unmoved. I have, however, always enjoyed our visits to such collections and the farms on which they were used. There is always something to arouse my interest. Despite my urban bias, I was impressed when Catherine Wilson led a Steering Group which produced an important report, Farming, Countryside and Museums, for the then Museums & Galleries Commission. The Steering Group later morphed into the Rural Life Museums Action Group. This whole activity seemed to me to be a recognition of the role the Society could play in helping to frame the future of a group of museums. It was, in my view, a highlight in the recent history of the society. EC

An abiding memory of my times at Folk Life conferences and reading the journal is just how relevant the areas and topics of study were to all that was happening in developing interpretation and tourism. It was also a group of like-minded characters who brought their own style to the various meetings. TS

As a novice member of a large and well-established National Museum, which had its own ways of doing things, the Society enabled me to meet with and listen to a wide range of experts. Their perspectives, their expertise, and their passion for their subject area, was readily shared with people like me. This tradition continues: the Society and its members are remarkably ‘unstuffy’. I’ve felt able to ask questions that I couldn’t have asked elsewhere, and I’ve heard things said which have impelled me to look again at my practice. I’ve got to know other parts of neighbouring countries quite well. The 2004 Conference, in Mellac, is particularly memorable in this respect and indicates a way ahead for the Society. We’ve been fortunate to have attracted members and delegates from Europe and beyond; surely our focus should now be on this wider horizon, as we bid farewell to what Professor David Marquand has described as ‘the decaying hulk known as the British state’. DR

SLFS is to be congratulated for effectively sponsoring into existence the Rural Museums Network over the past decade or more. It follows that my interests are primarily focused on material culture evidence, its preservation where of value and its interpretation, and for me the other great achievement of SFLS has been the publication of its journal, Folk Life. This is a thorough and systematic achievement over half a century and much to be admired. DV

One way or another, the Society for Folk Life Studies has exercised a remarkable influence on my life and interests […] Following the Glasgow lecture (Folk Life, 12), George Thomson, the then Director of the Ulster Folk Museum, had suggested a fowling fieldtrip to Rathlin. But this was not to be. Some years later I received a polite letter from a young Linda-May Ballard about to undertake fieldwork on Scotland’s mislaid island. Hopefully the reply was helpful; and some of Linda’s material appeared in Folk Life, 39. This was the same Linda-May Ballard who in Melrose (2005) invited what was to become a series of articles for Folk Life (47, 48:2, 49:1, 50:1, and forthcoming). Part 5 does indeed focus on Rathlin, albeit mainly consolidating material gathered by others — hardly surprising, given most islanders with first-hand experience of harvesting seabird eggs (never mind the birds themselves) have long since passed away. A real regret, therefore, that I had been unable to take up GBT’s invitation to meet with them some thirty-five or so years ago and record more of Rathlin’s fowling heritage. JB

The success of a scholarly society also lies in the quality of its journal and here for fifty years the Society has excelled, producing every year a journal of a consistently high standard. For the 1973 volume, when Geraint Jenkins was Editor, the journal adopted a distinctive type face for the words ‘folk life’ which has, in effect become the Society logo. Many members have contributed articles over the years. […] I have my own favourites which inevitably reflect my own interests: ‘The Denby Dale Pies: An Illustrated Narrative History’ by David Bostwick was published in volume 26 following an entertaining lecture at the Sheffield Conference. Then there is John Burrison’s article on ‘The Living Tradition of English Country Pottery’; and in his article on the Story of Burbage Wharf in volume 31, my former colleague, Roy Brigden, describes his quiet excitement at finding a virtually complete family and commercial archive lying untouched recording the operation of a business in wharfage and farming in Wiltshire stretching back almost 120 years. DE

Among the Society’s great strengths is that it publishes a highly regarded journal. This helps to focus the mind and gives members, as well as friends, a ‘map’ to read both the Society’s and the contributors’ lines of development over the years, covering a field broader than the strict definitions of anthropology. Other strengths include its ability to effectively recruit new officers over its lifespan, its generosity and perspicacity in offering a ‘student’ place at conferences, since recruiting new members, whatever their age, seems to me to be very high on the list of priorities. Perhaps it goes without saying, that an impressive spirit of conviviality characterizes Society meetings. CGK

An aspect of the Society which impressed me was the extent to which it had become representative of its target membership in the museums that concentrated their interests in aspects of material culture, whilst welcoming anyone from outside with similar interests. It is this wide-ranging membership which has enriched our annual conferences. It will be a pity if the struggling finances of museums brings about a reduction in the staff who can attend these events. One thing I regret, however, is the lack of a significant overlap of membership with other societies in similar fields. I am thinking in particular of the Folklore Society. I am hoping to try and rectify this situation over the next few years. EC

The Society, for me, is among many highly fruitful nodes in a whole network, often invisible (except when you are using it), that crosses over from one web to another, depending on the help or information you need or the project you are working on […] I would compare the Society, on a very human scale, to the British Library. Its regular members and occasional visitors love using it, the way your hands enjoy doing something they hardly need think about. However, a lot of thought has gone into this easiness and it is among the most attractive, if rather inimitable, of the Society’s qualities. CGK

The thing that struck me at the first [Folk Life] conference I went to (I had been previously to a conference of British Geographers which was very cut-throat and dog-eat-dog) was how nice everybody was. These were people who were leaders in their field but they would never see it as part of their role […] to run people down as I was used to in the cut-throat world of academe. It was a spirit of help and cooperation that struck me more than anything. JWD

SFLS maintains links with what I hold most dear: people, friendships, languages, places, and landscapes. BL

The future of the Society

A valuable feature of the Society has been the succession planning and the transfer of responsibilities to younger members with the right kind of support. We need to think outside the museum box and encourage membership by others who can contribute to our field of enquiry. BL

As to the future, I feel that not the least of the Society’s challenges and best endeavours probably lie in a closer linkage with other related (and probably special-interest) groups, such as the Rural Museums Network, and I imagine that this will be a feature of the next few years as all such groups face the challenge of sustaining, let alone increasing, their respective membership levels. DV

Like others in the Society, I have always hoped that it might do more to reach out to include studies of traditions and material culture relating to industrial and urban Britain. This, I believe could help strengthen the Society — attract new members — and ensure that it continues to have a strong future for the next fifty years! DE

But whither ethnology, now that the twentieth-century harvest is largely gathered in? The glory days maybe over, and economic pressures, competing disciplines, increasing specialization and compartmentalization are diverting ever-scarce resources away from nineteenth and twentieth century material culture and oral heritage. Today, of course, is always past and the stuff of ethnology ever-present, but rarely in the British Isles has it acquired more than a toe-hold in academia. It is not sociology, anthropology, or archaeology, and maybe its strengths do indeed lie more in recording, collecting, comparing, and contrasting commonplace activities, artefacts, and their associated traditions than in social theory, modelling, and creative conjecture? And museums may well be more of a natural home? But increasingly (and not altogether unreasonably), museums are required to operate as a community focus, an educational resource and visitor experience, and an economic driver for tourism. Other than in mainly national museums, detailed research has all-too-often become a ‘leisure-time’ and ‘retirement’ activity. So without the dedication and commitment of the Society for Folk Life Studies and its members, past and present, our knowledge and understanding of the stuff of ordinary workaday cultures and the impact of cross-cultural influences would be much the poorer. JB

After half a century of existence, is it not time that the Society’s raison d’être should be re-evaluated? How should the core subject matter be defined, and which theoretical and methodological approaches should be encouraged? Should the present professed concentration on British Isles’ material persist, or should the journal become more ‘international’ in its scope? In which case I believe a fundamental change would be required in its constitution. AG

Now, here is the reason I hope the SFLS will go on for another fifty years — not because I am a partisan of continuity at all costs (quite absurd!), but because I think it is within the scope of essentially cultural (that is, humanistic) groups and institutions that people are willing to look back and think ahead. As important as the present is in all our actions and thinking, we need the Society and its journal to escape from the burdens of ‘presentness’. There is also the fundamental question of tradition and transmission in the realm of collections and especially that tricky domain, intangible heritage. Here, the Society has often marshalled the human wherewithal to help museum folk navigate through these perilous times, but it has also empowered other people who have much to say about material culture with a human face and the hands skilled in making it. An asset we seem best to notice when it has escaped us. CGK

Contributors

GB: Gillian Bulmer; JB: John Baldwin; PB: Peter Brears; RB: Roy Brigden; EC: Eddie Cass; FCW: Fionnuala Carson-Williams; DE: David Eveleigh; AG: Alan Gailey; CGK: Cozette Griffin-Kremer; BL: Brian Loughbrough; TO: Trefor Owen; DR: Dafydd Roberts; CS: Christine Stevens; TS: Terry Stevens; DV: David Viner; RV: Roy Vickery; EW: Eurwyn Wiliam; JWD: John Williams-Davies.

yfol_a_11663783_sm0001.doc

Download MS Word (172.5 KB)Additional information

Notes on contributors

Steph Mastoris

Steph Mastoris joined the staff of Amgueddfa Cymru-National Museum Wales in 2004 as the first Head of the National Waterfront Museum in Swansea. Before this, he had worked in the museum services of the county of Leicestershire, and the city of Nottingham since 1978. Steph joined the Society for Folk Life Studies in 1993 and has served on its Council for a number of years. He has also held the post of Secretary (1999–2003) and is currently Conference Secretary (since 2006).

Correspondence to: Steph Mastoris, National Waterfront Museum, Maritime Quarter, Oystermouth Road, Swansea sa1 3rd, Wales, UK. Email: steph.mastoris@ museumwales.ac.uk

Notes

An index to Folk Life volumes 41–50 is available as an online supplement to the present issue. Please go to Supplementary Material 1 http://dx.doi.org/10·1179/0430877812Z.0000000007.S1

Notes

- Since this paper was researched, an archive for the Society has been established at St Fagans, National History Museum, near Cardiff (a part of Amgueddfa Cymru-National Museum Wales). Members of the SFLS past and present are therefore urged to contact the Society’s Secretary if they wish to offer for preservation any papers, photographs, or sound recordings they may have relating to the work of the Society.

- On Peate, see Trefor Owen, ‘Iorwerth Cyfeiliog Peate, 1901–1982’, Folk Life, 21 (1982–83), 5–11; Catrin Stevens, Iorwerth C. Peate (1986); H. J. Fleure, ‘Introduction’, in Geraint Jenkins (ed.), Studies in Folk Life: Essays in Honour of Iorwerth C Peate (1969). Many of Peate’s closest professional contacts contributed to Studies in Folk Life.

- Gwerin, ii.2 (December 1958), 50; ii.4 (December 1959), 143; iii.1 (June 1960), 1–2; iii.3 (June 1961), 113; iii.4 (December 1961), 163; iii.5 (June 1962), 225; and iii.6 (December 1962), 271–72; Iorwerth Peate, ‘The Society for Folk Life Studies’, Folk Life, 1 (1963), 3–4.

- Gwerin, iii.4 (December 1961), 163; and iii.6 (December 1962), 271–73. For examples of Peate’s forthright editorials, see Gwerin, i.2 (December 1956), 51–52; i.4 (December 1957), 146; and iii.5 (June 1962), 225–26. Gwerin iii.4, 163 encouraged readers to join the SFLS and included a membership application form.

- Alexander Fenton, ‘The Scope of Regional Ethnology’, Folk Life, 11 (1973), 9. Sadly, no other documentation is available that records this debate in any detail.

- Annual membership figures are available from the AGM reports that are reproduced in the Folk Life Newsletter from the late 1980s. Some earlier figures are cited in the ‘Notes and Comments’ sections in the first ten volumes of Folk Life, 1 to 10 (1963–72), passim.

- I am grateful to Alan Gailey and John Williams Davies for these observations. This fall-off of support by non-museum specialists can be seen in the changing membership of the ordinary committee members of the SFLS Council, published in each edition of Folk Life.

- For an account of the origins and development of the SHCG, see Steph Mastoris, ‘From GRSM to www.shcg.org.uk: Some Thoughts on the First 35 Years of the Social History Curators Group’, Social History in Museums, 34 (2010), 11–18. For an insight into the differing attitudes by members of the SHCG and SFLS, see May Redfern, ‘Social History Museums and Urban Unrest’, Social History in Museums, 34 (2010), 19–25, and David Fleming, ‘Social History in Museums: 35 Years of Progress?’, Social History in Museums, 34 (2010), 39–40.

- Steph Mastoris, ‘The Society’s Membership Survey’,Folk Life Newsletter, 16 (2001), 6.

- I am grateful to Alan Gailey for this information. Peter Brears served as President for only one year because a number of personal and professional circumstances combined to prevent him giving his full attention to the office for the rest of the three-year term (Peter Brears, pers. comm.).

- Trefor Owen, ‘Folk Life Studies: Some Problems and Perspectives’, Folk Life, 19 (1981), 5–16.

- Geraint Jenkins, ‘Interpreting the Heritage of Wales’, Folk Life, 25 (1986/7), 5–17.

- Alan Gailey, ‘Migrant Culture’, Folk Life, 28 (1989/90), 5–18.

- Brian Loughbrough, ‘Experiences of Places and People’, Folk Life, 31 (1992/3), 7–16.

- Ross Noble, ‘Presidential Address 1995 [Meeting the Challenge: Some Thoughts on the Future of Ethnology]’, Folk Life, 34 (1995/6), 7–13.

- Catherine Wilson, ‘‘I’ve got a brand new combine harvester … but who should have the key?’ Some thoughts on Rural Life Museums and Agricultural Preservation in Eastern England’, Folk Life, 41 (2002/3), 7–23.

- Roy Brigden, ‘Recording Change’, Folk Life, 48·1 (2010), 3–12.

- ‘Notes and Comments’, Folk Life, 1 (1963), 112.

- Linda-May Ballard, ‘Fifty Years of Folk Life’, Folk Life, 50·1 (2012), 1–6.

- ‘Editorial’, Folk Life, 18 (1980), 5–6; Alan Gailey, pers. comm.

- However, Eurwyn Wiliam comments that, ‘Geraint himself couldn’t stand anything to do with beliefs and customs, but as an editor he welcomed anything that would give a balance as well as fill a volume’.

- Geraint Jenkins (ed.), Studies in Folk Life: Essays in Honour of Iorwerth C Peate (1969), 335–338.

- Mastoris, ‘From GRSM to www.shcg.org.uk’, 11–18; Peter Brears, pers. comm.