Abstract

Background: Several classification systems have been proposed for non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL), of which Working Formulation (WF) and the recent Revised European American Lymphoma (REAL) classification are the two most widely used. There have been only a few studies comparing the two classification systems. The present study was undertaken in view of the paucity of literature comparing the foresaid classifications.

Methods: This retrospective and prospective study included 52 cases of NHL. These cases were examined thoroughly with the routine stains and immunohistochemistry using a panel comprising CD45, CD20, CD45RO, CD5, and CD30. All the cases were classified using the WF as well as the REAL classification, taking into account the immunohistochemical results.

Results: A wide age range and a slight male predominance were noted. The majority of cases were nodal, while 17% were extranodal. Using the WF, intermediate grade was the most common (65·38%), of which malignant lymphoma, diffuse large cell type and diffuse mixed small and large cell type were the two most frequent categories. On immunohistochemistry, 76·9% of the cases were B-cell immunophenotype. Of the various B-cell lymphomas, the most common was follicle center lymphoma and most common T-cell lymphoma was peripheral T-cell lymphoma. A comparison of the two classification systems revealed that T-cell neoplasms were grouped with B-cell lymphomas in the WF.

Conclusion: Though REAL classification requires a detailed immunohistochemical panel for thorough classification of all cases, the use of a basic panel of B- and T-cell markers allows the distinction between B- and T-cell lymphomas. Hence, REAL classification should be employed for categorization of NHL even in smaller centers with limited immunohistochemical panel.

Introduction

Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL) comprises of a heterogeneous mixture of neoplasms of different lymphoid cell lineages frozen at different stages of development.Citation1 Several classifications for NHLs have been put forth, starting with the earliest classification proposed by Gall and Mallory in the early nineteenth century.Citation2 In 1982, the Working Formulation (WF) was proposed which was meant to be a translation system between various classifications prevalent at that time.Citation3 The WF divided NHLs into three histological groups: low, intermediate and high grade based on their clinical behavior. A new classification, named REAL (Revised European American Lymphoma classification), was proposed in 1994, taking into account the various shortcomings of the WF. REAL classification was based on morphology, immunophenotype and cytogenetic data in cases of lymphoma.Citation4 To date, very few studies have been undertaken comparing REAL classification and WF.Citation5–Citation7

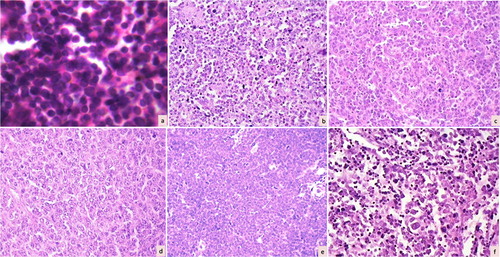

Figure 1. A panel of photomicrographs depicting various non-Hodgkin lymphomas according to the Working Formulation: (a) malignant lymphoma (ML) small lymphocytic (H&E, ×100); (b) ML follicular predominantly small cleaved cells (H&E, ×100); (c) ML follicular predominantly large cells (H&E, ×100); (d) ML diffuse large cell (H&E, ×100); (e) ML lymphoblastic (H&E, ×100); and (f) ML diffuse mixed small and large cells (H&E, ×100).

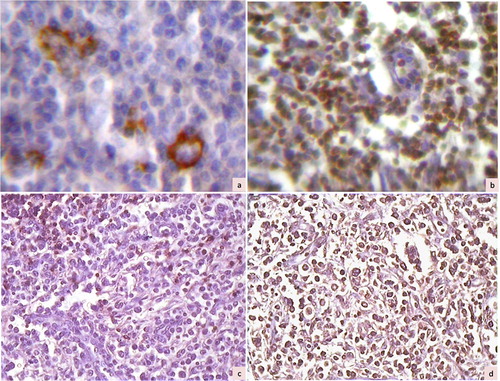

Figure 2. Immunohistochemical photomicrographs showing a case of T cell-rich B-cell lymphoma with large cells positive for CD20 (a, ×200) and small lymphocytes in the background staining for CD45RO (b, ×200). Another case of lymphoma (diffuse mixed small and large by Working Formulation) showing negative staining for CD20 (c, ×100) and diffuse positive staining for CD45RO (d, ×100), suggestive of T-cell lymphoma.

The present study was undertaken with an aim to compare the two classifications (WF and REAL) and to detect lacunae in the WF that led to the emergence of REAL classification. Our center being a secondary care center, we also aimed to evaluate the utility of a basic panel of immunohistochemistry in usage of the REAL classification.

Materials and Methods

This was a retrospective and prospective study over a period of 7 years (2000–2007) at a secondary care center. A total of 52 cases diagnosed as NHL were included in the study. The clinical details noted in these cases included: age, gender, site of involvement, presenting clinical features and the presence of extranodal involvement.

All the tissues were formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded. Routine stains, including hematoxylin and eosin and reticulin, were performed in all cases. Immunohistochemistry was performed using the streptavidin–biotin complex method with diamino benzidine as the chromogen. The monoclonal antibodies included: CD45 (leukocyte common antigen; Dako, Carpinteria, CA, USA), CD45RO (T-cell marker; Dako), CD20 (B-cell marker; Dako), CD5 (Biogenex, San Ramon, CA, USA), and CD30 (Biogenex).

All the cases were classified as per the WF using the routine stains. REAL classification was applied after consideration of the immunohistochemical staining results. A comparison was made between the two classifications and the mismatched cases were noted. These cases were reviewed for the possible reasons of mismatch.

Results

A wide age range of 10–95 years (mean: 40·8±18·01 years) was noted, with maximum number of patients in the second to fourth decades (55·7%). There was a slight male preponderance (male/female 2·1∶1). The site of involvement was nodal in 43 patients (82·7%) and extranodal in nine (17·3%) patients. Of the nodal cases, 25 patients (58·1%) presented with localized involvement of single group of lymph nodes, while the rest 18 patients (41·8%) had generalized lymphadenopathy. The most common nodal site of involvement was cervical lymph nodes (20 cases, 46·5%). Of the extranodal cases, five showed involvement of gastrointestinal tract (ileum in all five) and four in the tonsil.

WF

Using the WF, 13 cases (25%) were low grade, 34 (65·3%) were intermediate grade, and five (9·6%) were high grade. The two most common NHL according to WF were malignant lymphoma, diffuse large cell (13 cases, 25%), and diffuse mixed small and large cell (11 cases, 21·1%). The results of WF are summarized in and depicted in .

Table 1. Classification of NHL cases based on Working Formulation

REAL classification

The results of categorization according to the REAL classification are depicted in and . On immunohistochemical characterization, 40 cases (76·9%) were B-cell immunophenotype while 12 cases (23·1%) were of T-cell type. None of the cases showed dual positivity or negativity for both B- and T-cell markers. Of the B-cell NHLs, the two most common entities were follicle center lymphoma (17 cases, 32·7%) and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (13 cases, 25%). The most common T-cell neoplasm was peripheral T-cell lymphoma NOS (five cases, 9·6%) followed by precursor T-lymphoblastic lymphoma (four cases, 7·7%).

Table 2. Classification of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma cases based on REAL classification

Comparison of WF and REAL classifications

A comparison of categorization of our cases by both WF and REAL is shown in . As can be seen, categorization by WF combines B- and T-cell neoplasms together on morphological grounds alone. Of the seven cases of ML, small lymphocytic using the WF, one case was positive for T-cell markers, thus was classified as T-cell small lymphocytic lymphoma by REAL classification. Seven cases were diagnosed as ML, diffuse small cleaved cell by WF. Of these, four cases were B-cell follicle center lymphoma (three Grade 1 and one Grade 3), while two cases were diagnosed as marginal zone lymphoma and one as mantle cell lymphoma. Similarly, peripheral T-cell lymphoma (five cases) and anaplastic large cell lymphoma (one case) were grouped with B-cell lymphomas into ML, diffuse mixed small and large and diffuse categories in the WF. Of the five cases diagnosed as ML, lymphoblastic with WF, four were immunopositive for T-cell marker, thus being classified as T-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma using the REAL classification.

Table 3. Diagnosis of NHL before and after Immunohistochemistry

Discussion

NHL is a heterogeneous group of neoplastic proliferation of lymphoid cells. Over centuries, several classifications have been proposed for NHLs. The earliest of these was based on clinical and histopathological features as proposed by Gall and Mallory.Citation2 In 1970, Sheehan and Rappaport subdivided NHLs on the basis of growth pattern into nodular and diffuse and further cytological subtypes.Citation8 This was followed by Lukes and Collins’ classification based on the immunology into B- and T-cell lymphomas.Citation9 In 1975, Lennert et al developed the Kiel classification, which was based on the postulated relationship of neoplastic lymphoid cells to their normal counterparts in the immune system.Citation10Citation10,11 This classification was widely used in Europe. An extensive study sponsored by the National Cancer Institute led to the proposal of WF based primarily on clinical correlation especially survival curves.Citation3 However, WF was a histopathological classification without the use of immunological methods. In WF, NHLs were grouped into low, intermediate and high grade and a category of miscellaneous entities. Low-grade lymphomas have been considered indolent, while high-grade lymphomas were found to be highly aggressive and resistant to treatment. Intermediate-grade NHLs have been considered potentially curable with combination chemotherapy.Citation12 The WF was widely used due to the relative simplicity and ease of understanding. However, certain drawbacks that came to light included: (1) WF was intended to be a method of translation between the then existing classification; (2) WF categories were defined by survival data using the chemotherapy protocols used in 1970, which would lose relevance with new therapies; (3) no immunological data were included in WF; and (4) several entities like mantle cell lymphoma, marginal cell lymphoma, and low-grade lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue were not categorized.Citation4

Keeping in view these drawbacks, a new classification was put forth in 1994 termed as the Revised European American Classification of Lymphoid Neoplasms (REAL classification).Citation4 The REAL classification encompasses clinical, morphology, immunophenotype, and genetic factors. This classification recognized two major categories of NHL — B cell and T/NK (natural killer) cell neoplasms.Citation4 B- and T-cell lymphomas are further subdivided into precursor and peripheral lymphoid neoplasms. For pathologists to use REAL classification, immunophenotyping with a panel of antibodies is mandatory, especially for diagnosis of T-cell lymphoma and anaplastic large cell lymphomas.

Since the publication of the REAL classification, there have been only a few studies evaluating its usefulness by comparison with WF.Citation5–Citation7 These studies have shown that use of REAL classification provides additional information to the clinician due to identification of entities like mantle cell lymphoma.Citation5 A study from south-east Turkey compared WF and REAL classifications. The authors reported the intermediate grade as the largest group according to WF, while diffuse large B-cell lymphoma was the commonest lymphoma using the REAL classification.Citation13

The present study also compared the classification of NHL using the WF and REAL classification systems. With the WF, intermediate grade was the largest group (65·38%), of which ML, diffuse large cell type, was the commonest (25% of the cases). Similar results have been earlier reported from South-east Asian countries, including India.Citation14Citation14,15 This is in variance with the Western data, where malignant lymphoma, follicular type, was the most common type.Citation3

Immunohistochemistry on our cases showed B-cell lymphomas (76·9%) to be commoner than T-cell lymphoma (23·1%). This is similar to the previously reported frequency of B-cell lymphoma at 79·1% and 15·2% T-cell lymphoma.Citation6 Of the B-cell neoplasms, follicular lymphoma formed the largest category (32·69%) closely followed by diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (25%). This is slightly in variance with the earlier reported data, where DLBCL formed the commonest B-cell lymphoma followed by follicular lymphoma. This might be attributed to the difference in the distribution of patients due to the secondary care nature of the center where this study was conducted. B-cell small lymphocytic lymphoma formed 11·5% of the total number of cases, compared to the 5·7% reported in an earlier study by Naresh et al.Citation6 Among the subsets of T/NK-cell lymphoma, peripheral T-cell lymphoma was the most frequent (9·6%), followed by precursor T-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma (7·7%). This is similar to the incidence reported by Naresh et al.Citation6

In the present study, cases of peripheral T-cell lymphoma, intestinal T-cell lymphoma and anaplastic large cell lymphoma were classified along with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in the WF. It was difficult to differentiate between B- and T-cell neoplasms on the basis of morphological grounds alone. Similar views have been expressed by earlier studies.Citation4 Hence, immunophenotyping is mandatory for accurate classification of lymphoid neoplasms, which cannot be achieved using the WF.

Extranodal lymphomas, i.e. lymphomas occurring at sites other than lymph nodes, account for approximately 45% of all lymphomas.Citation13 Extranodal lymphomas may involve any site, including gastrointestinal tract, central nervous system, ear, nose, throat, thyroid, lung, salivary glands, thymus, gonads, orbit, and pleural or peritoneal cavities. In the present study, 17·3% of the cases involved extranodal sites, of which gastrointestinal tract (ileum) was the most frequent followed by tonsil. This is similar to those reported in an earlier study.Citation13 The histopathological subtype of NHL in extranodal sites, in the present study, included DLBCL, marginal zone lymphoma, and intestinal T-cell lymphoma using the REAL classification.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrates the utility of the REAL classification even at centers with only the basic immunophenotyping available. Use of the B- and T-cell markers allows the distinction between these two main groups of lymphomas. Hence, WF should be abandoned now in favor of the REAL classification. This would allow better and more uniform lymphoma reporting with the facility of possible comparison between various centers.

References

- Rosenberg SA. Classification of lymphoid neoplasms. Blood 1994;84:1359–60.

- Gall EA, Mallory TB. Malignant lymphoma. A clinico-pathological survey of 618 cases. Am J Pathol 1942;18:381–429.

- Rosenberg SA, Berard CW, Brown BW, Dorfmann RF, Glastein E, Hoppe RT, et al.. National Cancer Institute sponsored study of classification of non Hodgkin’s lymphoma: summary and description of Working Formulation for clinical usage. The non Hodgkin’s lymphoma classification project. Cancer 1982;49:2112–35.

- Harris NL, Jaffes ES, Stein H, Banks PM, Chan JK, Cleary ML, et al.. A revised European American classification of lymphoid neoplasms: a proposal from the International Lymphoma Study Group. Blood 1994;84:1361–92.

- Pittaluga S, Bijnens L, Teodorovic I, Hagenbeek A, Meerwaldt JH, Somer R, et al.. Clinical analysis of 670 cases in two trials of the European Organisation for the Research and Treatment of Cancer Lymphoma Cooperative Group subtyped according to the Revised European American Classification of Lymphoid Neoplasms: a comparison with Working Formulation. Blood 1996;87:4358–67.

- Naresh KN, Sriniwas V, Soman CS. Distribution of various subtypes of non Hodgkin’s lymphoma in India: a study of 2773 lymphoma using REAL and WHO classification. Ann Oncol 2000;11:63–7.

- Sweetenham JW, Smartt PF, Wilkins BS, Pellatt JC, Smith JL, Ramsay A, et al.. The clinical utility of the Revised European-American Lymphoma (R.E.A.L.) Classification: preliminary results of a prospective study in patients with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma from a single centre. Ann Oncol 1999;10:1121–4.

- Sheehan WW, Rappaport H. Morphological criteria in the classification of the malignant lymphomas. Proc Natl Cancer Conf 1970;6:59–71.

- Lukes RJ, Collins RD. Immunological characterization of human malignant lymphomas. Cancer 1974;34:1488–503.

- Lennert K, Mohri N, Stein H, Kaiserling E. The histopathology of malignant lymphoma. Br J Haematol (Suppl) 1975;31:193–203.

- Lennert K. Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: principles and application of the Kiel’s classification. Verh Dtsch Ges Pathol 1992;76:1–13.

- Portlock CS, Rosenberg SA. No initial therapy for stage III and IV non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma of favourable histologic types. Ann Intern Med 1979;90:10–3.

- Iskidogan A, Ayyildiz O, Buyukcelik A, Arslan A, Tiftik N, Buyukbayram H, et al.. Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma in east Turkey: clinico-pathologic features of 490 cases. Ann Haematol 2004;83:265–9.

- Intragumtornchai T, Wannakrairoj P, Chaimongkol B, Bhoopat L, Lekhakula A, Thamprasit T, et al.. Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma in Thailand: a retrospective pathologic and clinical analysis of 391 cases. Cancer 1996;78:1813–9.

- Kalyan K, Basu D, Soundararaghavan J. Immunohistochemical typing of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma-comparing working formulation and WHO classification. Indian J Pathol Microbiol 2006;49:203–7.