Abstract

The objective of this study was to analyze the clinical behavior and treatment policy of patients with primary testicular diffuse large B-cell lymphoma by retrospective analysis of 32 patients at our institute. All patients underwent orchidectomy. Anthracycline-based chemotherapy was administered to 27 patients (84·38%), six of whom also received rituximab; prophylactic intrathecal chemotherapy was given to seven patients (21·88%); and eight patients (25%) received prophylactic scrotal radiotherapy. Thirteen patients had relapse, among whom 12 cases were extranodal recurrences. Seven patients had central nervous system involvement, and four patients relapsed in the contralateral testis. The presence of B symptoms, poor Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status, left testicular involvement, central nervous system involvement, and first relapse within 1 year were associated with worse progression-free survival using univariate analysis. Poor Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status, left testicular involvement, and surgery alone were negative prognostic factors for overall survival.

Introduction

Primary lymphoma of the testis is a disease not frequently seen, which accounts for about 9% of testicular neoplasms and 1–2% of all non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas. However, it is the most common testicular malignancy in men over 50 years of age.Citation1–Citation4 Historically, primary testicular lymphoma has been reported to exhibit a poor prognosis with a 5-year overall survival rate of 16–50%.Citation5 The diagnosis is usually obtained after orchidectomy, and the most common histological subtype is diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), comprising 80–90% of all cases.Citation2–Citation4,Citation6 The typical clinical presentation is a unilateral painless testicular swelling that develops over a span of weeks to months, and sometimes sharp scrotal pain or hydrocele are also seen. Bilateral involvement may occur at initial presentation and has been reported in up to 35% of cases.Citation1,Citation7,Citation8

Primary testicular DLBCL shows an inclination to disseminate to the contralateral testis and the central nervous system (CNS), and involves other extranodal sites, less commonly skin, Waldeyer’s ring, lung, pleura, and soft tissues.Citation2,Citation8–Citation11 The optimal therapy remains controversial owing to the low incidence and absence of prospective studies. Early retrospective analyses have shown that, locoregional treatment only, such as orchidectomy alone or orchidectomy plus radiation therapy, even in patients with clinical stage I disease may relapse, ranging from 50 to 80%, with a third of these relapsing in the CNS or in the contralateral testis. Systemic doxorubicin-based chemotherapy can be helpful.Citation12–Citation15 Recently, treatment with orchidectomy followed by R-CHOP combination, with CNS prophylaxis, and prophylactic irradiation of the contralateral testis has been recommended as the first-line therapy for patients with limited disease; and management of patients with advanced or relapsed disease should follow the worldwide recommendations for nodal DLBCL.Citation1,Citation2,Citation8,Citation16

In the present study, we investigated the clinical features and treatment outcome of Chinese patients with primary testicular DLBCL by retrospective analysis of the cases at our institute.

Methods

From January 1985 to May 2009, 32 patients with primary testicular DLBCL diagnosed and treated in Fudan University Shanghai Cancer Center were included in the study. Patients who were initially diagnosed with DLBCL at a site outside the testis and had a late secondary testis involvement were excluded from this study. Approval for this retrospective study was obtained from the institutional review board at Fudan University Shanghai Cancer Center. Pathological specimens from all patients had been reviewed by a pathologist on the base of 2008 WHO classification system. All available clinical files were collected and data concerning age, B symptoms, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status, serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), Ann Arbor stage, presence and location of extranodal disease, initial treatment, response to treatment, site and time of failure, and status at last follow-up were recorded. Elevated LDH was >250 IU/l at our institution. Because of the retrospective nature of the study, not all variables were available for each patient.

The clinical stage was performed according to the Ann Arbor criteria on the basis of medical history, physical examination, laboratory investigation of blood routine, liver and renal function tests, computed tomography or positron emission tomography/computed tomography, and bone marrow biopsy. Patients with mono or bilateral involvement of the testes were defined as stage I, and patients with mono or bilateral testicular involvement associated with concomitant involvement of locoregional (retroperitoneal and/or iliac) lymph nodes were defined as stage II. Stages III–IV were defined by mono or bilateral testicular involvement with involvement of distant lymph nodes and/or extranodal sites. B symptoms were defined as a recurrent fever of >38°C, night sweats, and weight loss of >10% within 6 months prior to diagnosis. Complete remission (CR) was defined as the disappearance of all detectable clinical and radiographic evidence of disease and disappearance of all disease-related symptoms present before therapy; partial remission (PR) was defined as a ⩾50% reduction in the tumor bulk; stable disease (SD) was defined as less than a PR but not progressive disease (PD); PD was defined as a ⩾50% increase in the sum product of the greatest diameters of any previously identified tumor bulk or any new signs of disease during or at the end of therapy. Patients treated only by surgery were considered as being in CR if no signs of disease were noted 1 month after orchidectomy. All early deaths or incompletion of the planned treatment caused by treatment-related toxicity or any cause not related to lymphoma were not considered for response evaluation but only for progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS). PFS was measured from time of diagnosis to the time of primary treatment failure, relapse/progression, or death from lymphoma. OS was calculated from time of diagnosis to the time of either death from any cause or of last follow-up. Estimates of PFS and OS were made by the Kaplan–Meier method and differences between curves were analyzed using the log-rank test. The chi-square test was used to detect statistically significant differences for categorical variables. Statistical analysis was conducted using the SPSS 16·0 software package (Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Clinical features

A summary of the main clinical features in all patients is presented in . The median age at presentation was 57 years. In our patients, the first symptom was painless testicular swelling. Twenty-three patients presented with disease localized to the testis. The left testicle was involved in 13 (40·625%) patients, the right testicle in 19(59·375%) patients, and none had synchronous bilateral testicular involvement at diagnosis. The Ann Arbor stage classification was as follows: stage I in 23 (71·875%) patients, stage II in 7 (21·875%) patients, stage III in 2 (6·25%) patients, and stage IV in 0 patient. B symptoms were documented in 3 patients, 2 at stage I and 1 at stage II. Serum LDH level was elevated in 6 patients (18·75%), normal in 17 patients, and unknown in 9 patients. Twenty-one patients were International Prognostic Index (IPI) 0 or 1, 9 were IPI 2 or more, and 2 were unknown.

Table 1. Clinical characteristics

Initial treatments and outcome

All patients underwent orchidectomy as first therapeutic and diagnostic intervention. An overview of the treatment modalities and outcomes is presented in . In five patients, no further treatment was delivered. Twenty-seven patients (84·38%) received anthracycline-based chemotherapy (CHOP-like regimen), six of whom along with rituximab. The CHOP-like regimen contains cyclophosphamide, anthracycline (doxorubicin, epirubicin, or pirarubicin), vincristine (or vindesin), and prednisone. Twenty patients had ⩾4 cycles CHOP-like regimen (4–8 cycles); whereas two patients received only <4 cycles due to chemotherapy-related toxicity. The six patients having rituximab were treated with ⩾4 cycles R-CHOP-like.

Table 2. Patient characteristics and treatment modalities and outcomes

Prophylactic radiation to the contralateral testis was given to eight patients, and one patient had additional radiation to the involved inguinal lymph node areas. Seven patients (21·88%) received intrathecal methotrexate as CNS prophylaxis. The treatment response was able to be evaluated in 30 of the 32 patients, owing to treatment-related toxicity (two patients). A CR was achieved in 27 patients (90%) and a PR was observed in one patient (3·33%). An SD was observed in one patient (3·33%). The disease progressed in one patient (3·33%).

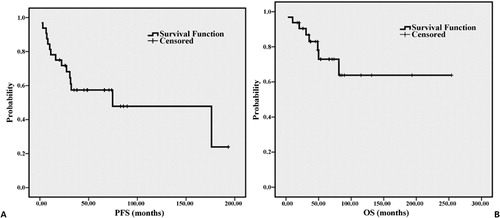

shows the survival analysis of the patients. The 5- and 10-year PFS rates were 57·4 and 47·8%, respectively, with a median PFS of 74·67 months (). The 5- and 10-year OS rates were 72·9 and 63·8%, respectively (). Estimation of median OS for the whole group is limited because the largest survival time is censored. Eight patients (25%) have died from lymphoma or lymphoma-related therapy, and five of them (62·5%) are within 3 years from diagnosis.

Pattern of relapse and analysis of prognostic factors

Presence of B symptoms, poor ECOG performance status, left testicular involvement, CNS involvement, and first relapse within 1 year were associated with worse PFS at univariate analysis. Poor ECOG performance status, left testicular involvement, and surgery alone were negative prognostic factors for OS at univariate analysis (). In five patients, orchidectomy was the sole treatment, and four of them were stage I disease who achieved a surgical CR after surgery. Their OS was significantly shorter than those of patients receiving additional therapy (P = 0·026); PFS was also shorter, but the difference did not reach statistical significance (P = 0·34). At a median follow-up of 48·9 months, 11 out of 27 patients (40·74%) in CR had disease relapse, six of whom died, amounting 75% of deaths in whole group. The duration of survival after relapse was poor. Five patients relapsed in 1 year from the time of diagnosis, three of whom died although having received second-line therapy.

Table 3. Univariate analysis of prognostic factors for PFS and OS

Sites of relapse

In the 32 patients, 13 (40·63%) had relapse, with a median time to relapse of 16·23 months (range: 1·97–176·10 months). Extranodal recurrence, with or without nodal disease, was reported in 12 (92·31%) of the 13 cases, and the site of the remaining one was unknown. In the 12 cases, only one patient was along with nodal site. The extranodal sites were as follows: CNS (7), contralateral testis (4), nasopharynx (2), vertebrae (1), skin of chest (1), lung (1), and soft tissue (1). In seven patients treated with intrathecal chemotherapy, one (14·29%) relapsed in the CNS; while in those not treated with intrathecal chemotherapy, six (24%) had a CNS relapse (P = 0·934), and one patient was unknown. In eight patients treated with prophylactic scrotal radiotherapy, two (25%) relapsed in the contralateral testis, and one patient was unknown; while in those not receiving prophylactic scrotal radiotherapy, two (8·33%) relapsed in contralateral testis (P = 0·444).

Discussion

Our study confirms the previously reported high rate of extranodal recurrence in patients with primary testicular DLBCL and the frequent involvement of unusual sites, which is less seen in DLBCL arising outside the testis. The reason for the observed high rate of extranodal relapses remains unknown.Citation17 The interpretations have been as follows: (1) the particular pattern of expression of adhesion molecules in testicular DLBCL results in poor adhesion of lymphoma cells to the extracellular matrix;Citation2,Citation18 (2) up to 60% of testicular DLBCLs lack expression of major histocompatibility type II antigens, thus malignant cells can escape from immune response through their inability to express tumor-associated antigens;Citation8,Citation19 and (3) chemotherapy may reduce efficacy in both testis and CNS, due to the blood–testis barrier and blood–brain barrier.Citation2

In 1877, testicular lymphoma was first reported by Malassez, and subsequently was defined as a clinical entity by Curling in 1878.Citation20 There is universal agreement that orchidectomy is the diagnostic and first therapeutic procedure of testicular lymphoma. The choice of further treatment is still a matter of debate. In the early 1980s, orchidectomy followed by adjuvant chemotherapy and retroperitoneal irradiation was introduced, because of a high rate of distant relapses in patients with localized disease treated by surgery alone or surgery plus locoregional radiotherapy.

In 1995, the recommendation had changed to a combined modality treatment, consisting of systemic doxorubicin-based chemotherapy, prophylactic intrathecal chemotherapy, and scrotal radiotherapy, because of the high rate of CNS and contralateral testis recurrence.Citation21 The best strategy to prevent CNS relapse still remains to be determined. Effect of intrathecal methotrexate on the CNS recurrences was not statistically significant in earlier published reports.Citation2,Citation8,Citation9 Therefore, other strategies to prevent CNS relapse need further exploring, such as whole brain irradiation, or a systemic chemotherapy that can penetrate into CNS.Citation22,Citation23 Since whole brain irradiation has significant neurotoxicity in elderly patients and testicular lymphoma is more often seen in the elderly population,Citation21 the effectiveness of systemic chemotherapy with CNS penetrating agents in high dose, such as methotrexate or cytarabine, can be considered.

Our present study was also not able to demonstrate a significantly reduced CNS relapse rate in patients treated with prophylactic intrathecal methotrexate. However, two reasons may contribute to this result. The first one was that prophylactic intrathecal methotrexate definitely could not reduce CNS relapse rate. The second one was that our sample was too small to acquire statistically significant result. The need for more effective CNS prophylaxis should be emphasized.Citation8

The efficacy of prophylactic radiation to the contralateral testis to reduce the risk of relapse at this site has been convincingly demonstrated in a number of studies.Citation2,Citation11 Almost all patients with testicular lymphoma are relatively elderly, and so, the need to preserve testicular function may not be so vital. Prophylactic radiation to the contralateral testis should be considered an essential part of the treatment. In our study, a significantly reduced contralateral testis recurrence rate in patients treated with irradiation of the contralateral testis was not shown, maybe because this was a small number of patients.

Potential benefit of the addition of rituximab to CHOP regimen remains to be better understood. As in nodal DLBCL, CHOP regimen plus rituximab has been shown to improve outcome in DLBCL of the testis;Citation8,Citation24,Citation25 however, when comparing R-CHOP versus CHOP regimen with regard to the CNS relapse rate, there was no statistical difference.Citation26 In spite of data suggesting the capacity of rituximab to cross the blood–brain barrier, there are several doubts. The role of rituximab in conferring an additional survival benefit and reduced CNS recurrence rate over CHOP alone should be addressed in a prospective randomized trial. There were few patients using rituximab and a small sample in our present study, and the outcome was difficult to assess.

Several variables associated with better OS and PFS have been reported:Citation2,Citation8,Citation27 good performance status, limited stage, low/low–intermediate IPI, absence of B symptoms, normal serum LDH and beta-2 microglobulin, absence of a bulky mass, absence of additional extranodal involvement, and right testicular involvement. We found that the presence of B symptoms, poor ECOG performance status, left testicular involvement, CNS involvement, and first relapse within 1 year were associated with worse PFS at univariate analysis. Poor ECOG performance status, left testicular involvement, and surgery alone were negative prognostic factors for OS at univariate analysis. Multivariate analysis would not be appropriate with 32 patients with so many different grouping in our study. Our results cannot confirm all the findings of other investigators on account of a small number of patients and not all variables available for each patient. Interestingly, we also found that left testicular involvement was associated with worse PFS and OS at univariate analysis, consisting with other investigators.Citation27 The right and left testicular veins drain into the inferior vena cava and the left renal vein, respectively. In theory, a potentially worse outcome would be associated with right testicular involvement because it drains to a vein of lesser pressure and that is in direct connection with the heart. Consequently, the chance of systemic spread is higher.Citation27 However, we found the opposite and we do not have a good explanation for this.

In conclusion, at the current time, modality treatment with orchidectomy followed by R-CHOP combination, with CNS prophylaxis, and prophylactic irradiation of the contralateral testis seems most promising.Citation1,Citation8,Citation23 Since primary testicular DLBCL is characterized by a particularly high risk of extranodal relapse even in cases with localized disease at diagnosis, and the duration of survival after relapse seems to be poor. Therefore, prophylactic intervention is significant, especially for CNS and contralateral testis. There are several novel agents emerging in the treatment of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma — Bendamustine (hybrid of purine analog and alkylator) and Bortezomib (proteasome inhibitor). These agents seem promising but have not been used in the treatment of primary testicular lymphoma. Improved understanding of the genetic and molecular characteristics of testicular lymphoma may help identify future patients at risk of CNS failure and tailor the treatment to the individual patient.Citation22

References

- Vitolo U, Ferreri AJM, Zucca E. Primary testicular lymphoma. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2008;65:183–9.

- Zucca E, Conconi A, Mughal TI, Sarris AH, Seymour JF, Vitolo U, et al.. Patterns of outcome and prognostic factors in primary large-cell lymphoma of the testis in a survey by the International Extranodal Lymphoma Study Group. J Clin Oncol 2003;21:20–7.

- Lagrange JL, Ramaioli A, Theodore CH, Terrier-Lacombe MJ, Beckendorf V, Biron P, et al.. Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma of the testis: a retrospective study of 84 patients treated in the French anticancer centres. Ann Oncol 2001;12:1313–9.

- Seymour JF, Solomon B, Wolf MM, Janusczewicz EH, Wirth A, Prince HM. Primary large-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma of the testis: a retrospective analysis of patterns of failure and prognostic factors. Clin Lymphoma 2001;2:109–15.

- Zucca E. Extranodal lymphoma: a reappraisal. Ann Oncol 2008;19(Suppl 4):77–80.

- Ahmad M, Khan AH, Mansoor A, Jamal S, Mushtaq S, Khan MA, et al.. Non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas with primary manifestation in gonads — a clinicopathological study. J Pak Med Assoc 1994;44:86–8.

- Al-Abbadi MA, Hattab EM, Tarawneh MS, Amr SS, Orazi A, Ulbright TM. Primary testicular diffuse large B-cell lymphoma belongs to the nongerminal center B-cell-like subgroup: a study of 18 cases. Mod Pathol 2006;19:1521–7.

- Mazloom A, Fowler N, Medeiros LJ, Iyengar P, Horace P, Dabaja BS. Outcome of patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the testis by era of treatment: the M. D. Anderson Cancer Center experience. Leuk Lymphoma 2010;51:1217–24.

- Fonseca R, Habermann TM, Colgan JP, O’Neill BP, White WL, Witzig TE, et al.. Testicular lymphoma is associated with a high incidence of extranodal recurrence. Cancer 2000;88:154–61.

- Vural F, Cagirgan S, Saydam G, Hekimgil M, Soyer NA, Tombuloglu M. Primary testicular lymphoma. J Natl Med Assoc 2007;99:1277–82.

- Pectasides D, Economopoulos T, Kouvatseas G, Antoniou A, Zoumbos Z, Aravantinos G, et al.. Anthracycline-based chemotherapy of primary non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma of the testis: the Hellenic Cooperative Oncology Group experience. Oncology 2000;58:286–92.

- Buskirk SJ, Evans RG, Banks PM, O’Connell MJ, Earle JD. Primary lymphoma of the testis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1982;8:1699–703.

- Duncan PR, Checa F, Gowing NF, McElwain TJ, Peckham MJ. Extranodal non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma presenting in the testicle: a clinical and pathologic study of 24 cases. Cancer 1980;45:1578–84.

- Sasai K, Yamabe H, Tsutsui K, Dodo Y, Ishigaki T, Shibamoto Y, et al.. Primary testicular non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: a clinical study and review of the literature. Am J Clin Oncol 1997;20:59–62.

- Møller MB, d’Amore F, Christensen BE. Testicular lymphoma: a population-based study of incidence, clinicopathological correlations and prognosis. The Danish Lymphoma Study Group, LYFO. Eur J Cancer 1994;30A:1760–4.

- Hasselblom S, Ridell B, Wedel H, Norrby K, Baum SenderM, Ekman T. Testicular lymphoma-a retrospective, population-based, clinical and immunohistochemical study. Acta Oncol 2004;43:758–65.

- Visco C, Medeiros LJ, Mesina OM, Rodriguez MA, Hagemeister FB, McLaughlin P, et al.. Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma affecting the testis: is it curable with doxorubicin-based therapy? Clin Lymphoma 2001;2:40–6.

- Drillenburg P, Pals ST. Cell adhesion receptors in lymphoma dissemination. Blood 2000;95:1900–10.

- Riemersma SA, Jordanova ES, Schop RF, Philippo K, Looijenga LH, Schuuring E, et al.. Extensive genetic alterations of the HLA region, including homozygous deletions of HLA class II genes in B-cell lymphomas arising in immune-privileged sites. Blood 2000;96:3569–77.

- Zicherman JM, Weissman D, Gribbin C, Epstein R. Best cases from the AFIP: primary diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the epididymis and testis. Radiographics 2005;25:243–8.

- Kristjansen PE, Hansen HH. Prophylactic cranial irradiation in small cell lung cancer — an update. Lung Cancer 1995;12(Suppl 3):S23–40.

- Verma N, Lazarchick J, Gudena V, Turner J, Chaudhary UB. Testicular lymphoma: an update for clinicians. Am J Med Sci 2008;336:336–41.

- Park BB, Kim JG, Sohn SK, Kang HJ, Lee SS, Eom HS, et al.. Consideration of aggressive therapeutic strategies for primary testicular lymphoma. Am J Hematol 2007;82:840–5.

- Vitolo U, Zucca E, Martelli M, Chiappella A, Baldi I, Balzarotti M, et al.. Primary diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the testis (PTL): a prospective study of rituximab (R)-CHOP with CNS and contralateral testis prophylaxis. Results of the IELSG 10 study. Blood 2006;108:65a–6a.

- Avilés A, Nambo MJ, Cleto S, Neri N, Huerta-Guzmán J. Rituximab and dose-dense chemotherapy in primary testicular lymphoma. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma 2009;9:386–9.

- Feugier P, Virion JM, Tilly H, Haioun C, Marit G, Macro M, et al.. Incidence and risk factors for central nervous system occurrence in elderly patients with diffuse large-B-cell lymphoma: influence of rituximab. Ann Oncol 2004;15:129–33.

- Gundrum JD, Mathiason MA, Moore DB, Go RS. Primary testicular diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: a population-based study on the incidence, natural history, and survival comparison with primary nodal counterpart before and after the introduction of rituximab. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:5227–32.