Abstract

The retrospective epidemiological study of Latin Americans with transfusional hemosiderosis is the first regional patient registry to gather data regarding the burden of transfusional hemosiderosis and patterns of care in these patients. Retrospective and cross-sectional data were collected on patients ⩾2 years with selected chronic anemias and minimum 20 transfusions. In the 960 patients analyzed, sickle-cell disease (48·3%) and thalassemias (24·0%) were the most frequent underlying diagnoses. The registry enrolled 355 pediatric patients (187 with sickle-cell disease/94 with thalassemia). Serum ferritin was the most frequent method used to detect iron overload. Complications from transfusional hemosiderosis were reported in ∼80% of patients; hepatic (65·3%), endocrine (27·5%), and cardiac (18·2%) being the most frequent. These data indicate that hemoglobinopathies and complications due to transfusional hemosiderosis are a significant clinical problem in the Latin American population with iron overload. Chelation therapy is used insufficiently and has a high rate of discontinuation.

Introduction

Long-term transfusion therapy, a routine treatment for patients with severe anemia resulting from disorders such as thalassemia, sickle-cell disease (SCD) and myelodysplasia, inevitably leads to iron overload and related complications.Citation1–Citation3 The clinical consequences of transfusional hemosiderosis include cardiomyopathy, liver damage, endocrine dysfunction, arthropathy, and skin pigmentation.Citation4 Cardiomyopathy is more prominent in patients with transfusional hemosiderosis than in those with hereditary hemochromatosis, likely due to the rapid rate of iron loading.Citation5 In thalassemia major, iron-induced cardiomyopathy is the chief cause of deathCitation6,Citation7 and has been observed in thalassemia intermedia,Citation8 SCD,Citation9 and myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS).Citation10

Iron-chelation has become an essential component of the treatment of patients with chronic, transfusion-dependent anemias and iron overload.Citation11 Deferoxamine has been the standard iron chelator for many decades, and has increased life expectancies of patients with thalassemia major.Citation12–Citation14 More recently, two oral iron chelators, deferiprone (Ferriprox®, ApoPharma) and deferasirox (Exjade®, Novartis) have been shown to be safe and effective alternatives to deferoxamine.Citation15–Citation18 Despite the effectiveness of iron-chelation, compliance with parenteral treatment is problematic and often leads to suboptimal outcomes.Citation11 Recent studies suggest that the use of an oral chelator such as deferasirox may improve patient compliance.Citation17,Citation19

The incidence of diseases associated with transfusional hemosiderosis is higher among certain ethnic groups and in defined geographic regions. Latin America is characterized by relatively free miscegenation of populations of Mediterranean and African ancestry over the past few centuries, thus facilitating the spread of hemoglobin variants that are responsible for SCD and thalassemias. In many Latin American countries, the burden of such diseases as well as their patterns of care and related consequences, such as transfusional hemosiderosis, is largely unknown. This led to the design of a Retrospective Epidemiological study of Latin American patients with Transfusional Hemosiderosis (RELATH). The objective of this registry was to gain insight about the burden of transfusional hemosiderosis and patterns of care for children and adults with transfusional iron overload in Latin America. We report on the general characteristics and features of iron overload and its complications, as well as chelation strategies in patients enrolled in RELATH.

Methods

Study design

RELATH was an international, multicenter, observational study conducted in nine Latin American countries: Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, Mexico, Panama, Peru, Trinidad & Tobago and Venezuela. The primary objective was to investigate the magnitude of the problem and patterns of iron overload in Latin America by quantifying the number of patients with transfusion-related iron overload. Eligible research sites were tertiary-care hematology centers performing at least 200 monthly consultations or located in cities with at least 1 million inhabitants. Retrospective and cross-sectional data on eligible children and adults were collected by participating physicians. There were no interventions or clinic visits required; therefore medical decisions were not influenced by this observational study. Data collection took place between September 2006 and January 2008. Data regarding complications of iron overload were categorized according to system organ class and major category. Supplementary information was collected verbatim. RELATH was conducted in accordance with international and local ethics and regulatory standards, and the protocol was approved by the institutional review boards of all participating centers. Either written informed consent from patients or an informed consent waiver was obtained from all institutional review boards.

Patient eligibility

Eligible patients were aged 2 years or older and had to have been seen in consultation at least once since January 2004. Patients had to have any disorder requiring chronic red blood cell (RBC) transfusions, including, but not limited to, any of the following: beta-thalassemia major; beta-thalassemia intermedia; sickle-cell anemia (homozygous); MDS [in any of three circumstances: (1) if, according to World Health Organization criteria they could be classified as having refractory anemia with or without ringed sideroblasts, refractory cytopenia with multilineage dysplasia, refractory sideroblastic cytopenia with multilineage dysplasia, 5q-syndrome, or unclassified myelodisplasia; (2) if, according to the International Prognostic Scoring System they belonged to the low- or low-intermediate-risk categories; or if (3) they had MDS outside the aforementioned categories but with indication for allogeneic bone-marrow or stem cell transplantation]; aplastic anemia; Blackfan-Diamond anemia; or other transfusion-dependent disorders.Citation20Citation20,21 Additional eligibility criteria were receipt of at least 10 RBC transfusions in the past, and at least one previous value of either serum ferritin >1000 μg/l or liver iron content (LIC) >2 mg/g dry weight.Citation22 If serum ferritin and LIC results were not available, patients with any of the previously listed diagnoses were eligible if they had documented evidence of ⩾20 RBC transfusions. Patients with any type of acute leukemia were not eligible for participation.

Children were evaluated for complications of iron overload including endocrine (growth retardation, gonadal insufficiency, diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism, and hypoparathyroidism), cardiac, and hepatic complications.

Trial methodology has been described elsewhere and preliminary results have been published.Citation24 All analyses were descriptive in nature.

Statistical analysis

The a priori sample size of approximately 1000 patients was not calculated on the basis of statistical assumptions regarding endpoints. Rather, this sample size was estimated on the basis of the expected number of patients that would be feasibly accrued by the participating institutions. All patients in the database who fulfilled inclusion and exclusion criteria comprised the analysis population. The data were analyzed to define the prevalence and clinical features, as well as to identify and characterize treatment patterns in four subgroups defined by the primary diagnosis: sickle-cell anemia, thalassemia, MDS, and other. The available data were analyzed using the observed-cases dataset, i.e. there was no imputation of missing values. Although most analyses are descriptive in nature, comparisons between groups were performed in some cases. For continuous variables, Student’s t-test was used, and the chi-square test was used for categorical variables. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS software, version 9.1.3, and two-sided P values <0·05 were considered significant.

The pediatric evaluation includes the subset of pediatric patients age 2 to ⩽18 years and focuses on those with SCD or thalassemia.

Results

Patient characteristics

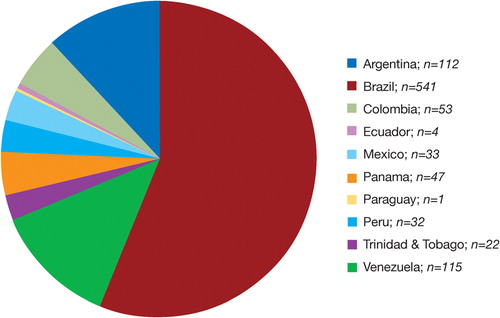

The registry population comprised 975 patients, 15 of whom were excluded from analysis (acute leukemia; n = 7, inadequate number of prior TBC transfusions; n = 6, or missing date of birth; n = 2). The highest percentage of patients were enrolled in Brazil (56·4%), Venezuela (12·1%), and Argentina (11·8%) (). Caucasian/Hispanic (56·3%) and African (37·0%) ancestries predominated (). The mean age in the total population was 28·5 years while that of patients with MDS was substantially older (62·7 years). The male/female ratio was balanced in the overall population and in each of the subgroups with the exception of other diagnosis where there were more males (59·9%) than females (40·1%).

Table 1. Demographics and patient characteristics

The most frequent underlying diagnoses were sickle-cell anemia (48·3%), thalassemia (24·0%), and MDS (7·2%) (). In the 60 patients with MDS, 18 (30·0%) were international prognostic scoring system Low risk, and 28 (46·7%) Intermediate-1 risk. In 20·5% of patients with other diagnoses, including aplastic anemia (n = 86), pure red cell aplasia (n = 16), Blackfan-Diamond anemia (n = 15) and other transfusion dependent disorders (n = 80).

Table 2. Iron overload complications in the overall population

There were 355 pediatric patients including 187 with SCD, 94 with thalassemia, 69 with other transfusion-dependent disorders, and 5 with MDS. Due to the small numbers of patients with MDS and individual transfusion-dependent disorders (i.e. refractory anemia with ringed sideroblasts, refractory cytopenia with multilineage dysplasia, refractory sideroblastic cytopenia with multilineage dysplasia, and refractory anemia with excess blasts), summary data are presented for SCD and thalassemia only. The mean age of the total population was 10·9 years. Patients with SCD were slightly older (mean 11·6 years) than the general population of pediatric patients and those with thalassemia were slightly younger (10·3 years) (). Centers in Brazil contributed the greatest percentage of patients (n = 182; 51·3%) followed by Argentina, Venezuela, Colombia and Panama. The majority of patients with SCD (86%) were from Brazil and Panama while the majority of those with thalassemia (87·3%) were from Brazil, Venezuela, Argentina and Trinidad & Tobago. The racial distribution among pediatric patients mirrored that of the general population.

The overall population was transfused as evidenced by the percentage of patients with a history of least 20 RBC transfusions before inclusion or had a serum ferritin level >1000 μg/l (mean level of 2607 μg/l) (). A comparison of the age distribution of patients according to the number of prior RBC transfusions showed that those with a history of ⩾20 transfusions were significantly younger (mean age 27·8 years) than those with 10 to 19 prior transfusions (mean age 33·6 years; P = 0·012). Among pediatric patients, there was a significant association between subgroups of diagnoses and the number of RBC transfusions (P<0·007). Compared with children with SCD, and with the total population of patients in the registry, pediatric patients with thalassemia had a greater transfusion history as evidenced by a higher annual average number of transfusions (13·3 versus 11·8 and 9·6, respectively), a larger percentage of the population who had received ⩾20 transfusions (93·6 versus 87·0 and 82·4%, respectively), and a lower average age among the patients who had received ⩾20 transfusions (10·4 years versus 12·2 and 11·2 years respectively).

The level of hemoglobin at which RBC transfusions were initiated was 7 g/dl or higher in 68·3% of all cases, and 6 g/dl or less in 22·8%. The hemoglobin threshold for transfusion was generally higher in patients with thalassemia (9 g/dl in 58·7% of patients) as compared to other diseases. There was no significant difference in the proportion of patients related to the number of prior RBC transfusions among the diagnostic subgroups although among patients with other diagnoses, the mean age of those with a history of ⩾20 RBC transfusions was significantly lower (31·1 years) than the patients who had received ⩾10–<20 transfusions (42·8 years; P = 0·007).

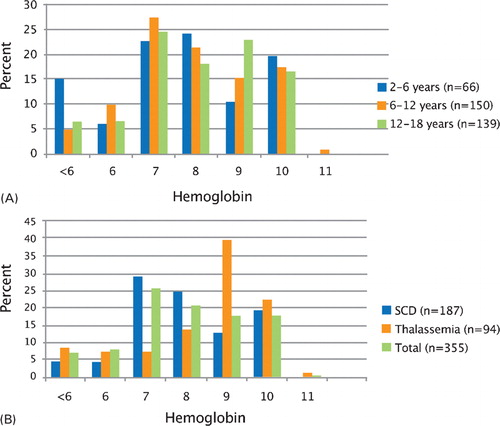

depicts the hemoglobin levels at which transfusions were initiated in the pediatric population by age (percentage of population) and disease (percentage of population). The threshold for initiation of transfusion therapy was a hemoglobin level of 7 to 10 g/dl in 81% of the total population. The threshold for initiation of transfusion therapy appeared to be lower for children 2 to 6 years (21·3% at hemoglobin ⩽6 g/dl versus 14·7 and 13% in 6 to 12 years old, and 12 to 18 years old, respectively) (). Transfusion therapy was initiated at hemoglobin ⩽9 g/dl in 78·8, 78·6, and 78·5% of children 2–6, 6–12, and 12–18 years, respectively. In patients with thalassemia, it was most common to initiate transfusions when hemoglobin levels were ⩾less than 8 g/dl (76·6%) (). In patients with SCD, the threshold for initiation of transfusions appeared to be slightly lower; 56·7 and 85·6% of patients initiated transfusion with hemoglobin levels ⩾8 g/dl and ⩾7 g/dl, respectively.

Iron overload

Serum ferritin, transferrin saturation, and echocardiogram (measured in 96·3, 21·6, and 25·0% of patients, respectively), were the methods most frequently tests used to assess iron overload. Median serum ferritin levels were similar in the overall patient population and in each of the diagnosis subgroups () but were higher in pediatric patients with thalassemia than with SCD. Serum ferritin levels were >1000 ng/ml for 91·6% of patients with sickle-cell anemia, 95% of those with thalassemia, 92·8% of those with MDS, and 88·3% of those with other diagnoses. The thalassemia population had a greater percentage of children with serum ferritin levels >1000 mcg/dl (94·7%) than either the SCD (89·8%) or the total population (90·7%).

Of note, only 90 patients (9·5%) had undergone assessment of LIC of whom 36 had LIC>2 mg Fe/g dry weight (dw). Mean LIC in the 37 patients for whom quantitative data were available was 16·0±10·5 mg Fe/g dw, 15·1±9·5 mg Fe/g dw in the subset of 34 patients with thalassemia and 26·9±17·8 mg Fe/g dw in the 3 patients with other diagnoses. Liver iron content values were available in only 30 children (20 with thalassemia, 7 with SCD and 3 other diagnosis). Eighteen children had LIC<2 mg/g dw. The mean LIC in the 12 children with LIC>2 mg/g dw, all of whom had thalassemia, was 15·7±8·4 mg/g dw.

Complications related to iron overload

Overall population

Complications considered to be related to iron overload were reported in 82·1% of the overall population, ranging from a low of 68·1% of patients with MDS, 70·6% of patients with other diagnoses, 86·6% of patients with SCD to 87·1% of patients with thalassemia ().

Complications of iron overload were reported in 288 (81·1%) patients (85·6% of patients with SCD and 80·9% of patients with thalassemia). The most commonly reported complications were hepatic, identified in 223 (62·8%) patients (). The most commonly reported hepatic complication was abnormal bilirubin reported in more patients with SCD (56·7%) than with thalassemia (34·0%). Abnormal liver enzymes were reported in 40·6% of the total population, and in 41·2 and 43·6% of patients with SCD and thalassemia, respectively.

Table 3. Hepatic complications in pediatric patients with transfusional iron overload

Although endocrine abnormalities were reported in each of the subgroup, there was a greater prevalence in the 230 patients with thalassemia; growth curve <50th percentile in 21·7%, growth hormone deficiency 7·8% of patients with thalassemia, luteinizing hormone and follicle stimulating hormone deficiency in 9·1%, T4 deficiency and elevated thyroid stimulating hormone in 9·6% and hypocalcemia in 7·0%. A higher rate of hyperglycemia was reported in patients with MDS (21/69; 30·4%) which may have reflected the older patient age within this subgroup.

Cardiac abnormalities included decreased left ventricular function in 2·6% and congestive heart failure in 4·9% of the overall population. Congestive heart failure was most commonly reported in patients with sickle-cell anemia (6·7%). Complications of hepatic iron overload were among the most common abnormalities reported (). Evidence of hepatic iron overload was most prevalent in patients with MDS, with 78·3% of patients having elevated liver function enzymes and 88·4% having abnormal bilirubin. As with hyperglycemia, underlying disease, age and co-morbidities may have contributed to the incidence of hepatic abnormalities in this subgroup.

Skin pigmentation was most prevalent in the patients with thalassemia (21·7%) and other diagnoses (22·8%). Arthropathy was most common among patients with other diagnoses (4·6%).

Pediatric population

Hepatic complications were reported in all age groups including 36 (54·5%) of children 2 to 6 years, 97 (64·7%) of those age 6 to 12 years, and 90 (64·7%) of children 12 to 18 years. Abnormal liver enzymes were reported in similar proportions of patients within each age group while abnormal bilirubin and abnormal liver ultrasound were reported in lower proportions of children age 2 to 6 years. Various types of viral hepatitis were also reported: Hepatitis C in 10 patients (2·8%), Hepatitis B in 5 (1·4%) patients, and unknown type and other in 4 (1·1%) patients each.

Cardiac complications were reported in 28 (8·0%) pediatric patients with the most commonly reported abnormality being symptomatic congestive heart failure in 7 (3 with SCD, 3 with thalassemia and 1 with other transfusion-dependent disorder). Symptomatic congestive heart failure was reported in small numbers of patients in each age group (2 patients’ age 2 to 6 years, 3 patients’ age 6 to 12 years, and 2 patients’ age 12 to 18 years).

Endocrine complications, comprised of growth retardation, gonadal insufficiency, diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism, and hypoparathyroidism, were reported in 12·3% of pediatric patients with SCD and 38·3% of patients with thalassemia. The most commonly reported complication related to growth was growth <50th percentile in 72 patients overall (20·3%); 19 (10·2%) patients with SCD and 26 (27·7%) with thalassemia. Hypogonadism was reported in 11 patients (3·1%) including 8 patients (8·5%) with thalassemia. Complications of diabetes mellitus (most commonly hyperglycemia), hypothyroidism (T4 deficiency/TSH elevation), and hypoparathyroidism (hypocalcemia) were each reported in <5% of patients. Hyperpigmentation was reported as a complication in 3 patients (1·6%) of patients with SCD and 17 patients (18·1%) of patients with thalassemia.

Iron chelation

Iron chelation was used in only 46·3% (n = 954) of patients. Serum ferritin was the preferred marker for initiation of chelation therapy (85·3%), and at the time of the data collection, only deferoxamine was widely available in the participating countries. Only a few patients were treated with deferasirox (13·6%). The rate of chelation therapy discontinuation was 20% (n = 441), primarily attributed to poor compliance and drug availability. On average, 58% of patients who received chelation therapy were treated >150 days per year.

Discussion

It has been estimated that approximately 1·5 million people in the United States are affected by iron overload.Citation23 The corresponding figure for Latin America, a world region with slightly over 500 million inhabitants, is currently unknown. Latin America is comprised of countries with medium to low income which have seen improvement in the provision of health care including recognition of the morbidity and mortality associate with birth defects and genetic disorders. Reliable data regarding the epidemiology of hematologic diseases associated with transfusional hemosiderosis in Latin America are lacking. It has been noted that delay in diagnosis of these hematologic disease and iron overload are a significant problem in Latin America which may be compounded by the lack of genetic screening.Citation24,Citation25 This is the first registry to describe the extent of the clinical problem in children with thalassemia and SCD across multiple countries in Latin America.

Latin America is unique in that the population is comprised of multiple comingled races and ethnicities (indigenous Amerindians, Europeans and Africans).Citation26–Citation29 The distribution of thalassemia and SCD in the registry population followed known genetic and population patterns with thalassemia predominating in countries with greater European influence (e.g. Argentina) and SCD identified more commonly in countries with a higher concentration of indigenous populations and African migrants (Brazil, Panama).

The main limitation of this registry was its retrospective nature, which precludes the accurate determination of the incidence of several important indicators of iron overload and its clinical consequences. However, the large sample size, especially with regard to the two most frequent diagnostic groups (SCD and thalassemias), provides important information of the prevalence of iron overload and its complications, in the Latin American countries contributing with higher numbers of patients.

Treatment recommendations for the management of thalassemia are to maintain hemoglobin levels at 9–10 g/dl with transfusions administered every 2 to 5 weeks.Citation1,Citation2 While transfusions are utilized in SCD, the extent of their use is dependent on symptomatology and requirements are lower than in thalassemia.Citation24 Therefore, it is not unexpected to find that children with thalassemia had received greater numbers of transfusions than those with SCD. The lower threshold for initiation of transfusion therapy in the very young patients (2–6 years) may be attributed to a greater ability to tolerate lower hemoglobin levels.

Iron overload is the most serious complication from the chronic administration of potentially life-saving RBC transfusions. Identification of patients at risk for iron overload has thus become an essential component of care for all those individuals with transfusion-dependent anemias. In those patients, rapid iron loading results from repeated RBC transfusions. Since one unit of RBCs contains between 200 and 250 mg of iron, a patient (30 kg, not adult) with chronic anemia receiving one or two RBC units per month may receive a daily iron excess of up to 0·5 mg/kg, which translates into 3–6 g within 1 year.Citation3 Thus, patients may become iron-overloaded with as few as 10 to 20 transfusions of RBCs.

In children with SCD, RBC transfusions have been increasingly used to prevent strokes, one of the chief causes of morbidity in this population.Citation30,Citation31 In addition, the majority of adult patients with SCD require RBC transfusions on a chronic basis. Some studies suggest that mortality among patients with SCD is significantly higher among those with concomitant iron overload.Citation32 In the present study, SCD was the most frequent underlying diagnosis, and 86·6% of such patients had complications from iron overload. The most frequent involved the liver and heart, whereas endocrine complications were reported in only 11·6% of patients with SCD. In the thalassemia patient group, half of the patients were reported to have at least one endocrine complication. This higher frequency of endocrine complications in patients with thalassemias, in comparison with patients with SCD is consistent with previous reports.Citation33–Citation35 Among patients with thalassemias, hypogonadism was the most prevalent endocrinopathy, followed by growth failure, whereas the latter was the most prevalent endocrinopathy among patients with SCD undergoing chronic transfusion.Citation35

In the pediatric population, complications of iron overload, most commonly hepatic abnormalities and growth retardation, were observed in a significant percentage of the pediatric population evaluated in RELATH. The hepatic and cardiac complications observed are of particular concern, due to high rates of associated morbidity and cost of care. Cardiac iron overload has been documented in younger children, particularly those without access to or with irregular use of chelation therapy.Citation36 Decreased growth velocity and delay in onset of puberty are a known outcome of thalassemia which has, in part, been attributed to iron overload and suboptimal chelation in pediatric patients in developing countries.Citation37–Citation39

Although not discussed here, preliminary evidence from the RELATH registry indicated that approximately 40% of enrolled patients were receiving chelation therapy.Citation24 Increased use of chelation therapy may lead to improvements in morbidity in this population. Management with chelation therapy can improve survival of patients with thalassemia major and has been associated with decreased incidence of cardiac iron overload in children with transfusions dependent anemias.Citation14,Citation36,Citation40–Citation42

Serum ferritin levels were the most widely used assessment of iron load. Serum ferritin is an indirect measurement of iron burden that fluctuates in response to a range of physiologic abnormalities; however, it is the easiest test to perform and least expensive method available.Citation3 Although results are conflicting, serum ferritin has been shown to correlate with other measures of iron load such as LIC and liver function tests.Citation43 While MRI equipment can be found in many hospitals in the region, ready access to MRI for assessment of LIC is limited by lack of trained personnel and cost. Interestingly, in our study as in a prior report almost all patients in whom LIC was assessed in the current study had thalassemias versus SCD.Citation35 The reasons for such findings remain unknown and may be worthy of further investigation.

Conclusion

The current study presents a cross-sectional view of the prevalence of transfusional hemosiderosis in Latin America, suggesting that most patients receiving chronic RBC transfusion for anemias undergo insufficient evaluation for the presence of iron overload. In this population, less than half were receiving iron-chelation therapy. A significant proportion of these patients discontinue iron chelation mainly because of poor patient compliance and interruption in drug availability. As a result, most develop some of the expected preventable complications of untreated iron overload. Finally, the study suggests that a disease registry is feasible in Latin America, providing valuable ‘real life’ information on disorders that contribute to morbidity and mortality in this world region.

References

- Cazzola M, De Stefano P, Ponchio L, Locatelli F, Beguin Y, Dessi C, et al.. Relationship between transfusion regimen and suppression of erythropoiesis in betathalassaemia major. Br J Haematol 1995;89:473–8.

- Cazzola M, Borgna-Pignatti C, Locatelli F, Ponchio L, Beguin Y, De Stefano P. A moderate transfusion regimen may reduce iron loading in beta-thalassemia major without producing excessive expansion of erythropoiesis. Transfusion 1997;37:135–40.

- Porter JB. Practical management of iron overload. Br J Haematol 2001;115:239–52.

- Schafer AI, Cheron RG, Dluhy R, Cooper B, Gleason RE, Soeldner JS, et al.. Clinical consequences of acquired transfusional iron overload in adults. N Engl J Med 1981;304:319–24.

- Andrews NC. Disorders of iron metabolism. N Engl J Med 1999;341:1986–95.

- Borgna-Pignatti C, Rugolotto S, De Stefano P, Piga A, Di Gregorio F, Gamberini MR, et al.. Survival and disease complications in thalassemia major. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1998;850:227–31.

- Zurlo MG, De Stefano P, Borgna-Pignatti C, Di Palma A, Piga A, Melevendi C, et al.. Survival and causes of death in thalassaemia major. Lancet 1989;2:27–30.

- Aessopos A, Farmakis D, Karagiorga M, Voskaridou E, Loutradi A, Hatziliami A, et al.. Cardiac involvement in thalassemia intermedia: a multicenter study. Blood 2001;97:3411–6.

- Batra AS, Acherman RJ, Wong WY, Wood JC, Chan LS, Ramicone E, et al.. Cardiac abnormalities in children with sickle cell anemia. Am J Hematol 2002;70:306–12.

- Greenberg PL. Myelodysplastic syndromes: iron overload consequences and current chelating therapies. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2006;4:91–6.

- Beutler E, Hoffbrand AV, Cook JD. Iron deficiency and overload. Hematology (Am Soc Hematol Educ Program) 2003:40–61.

- Brittenham GM, Griffith PM, Nienhuis AW, McLaren CE, Young NS, Tucker EE, et al.. Efficacy of deferoxamine in preventing complications of iron overload in patients with thalassemia major. N Engl J Med 1994;331:567–73.

- Modell B, Khan M, Darlison M. Survival in beta-thalassaemia major in the UK: data from the UK Thalassaemia Register. Lancet 2000;355:2051–2.

- Olivieri NF, Nathan DG, MacMillan JH, Wayne AS, Liu PP, McGee A, et al.. Survival in medically treated patients with homozygous beta-thalassemia. N Engl J Med 1994;331:574–8.

- Olivieri NF, Brittenham GM, McLaren CE, Templeton DM, Cameron RG, McClelland RA, et al.. Long-term safety and effectiveness of iron-chelation therapy with deferiprone for thalassemia major. N Engl J Med 1998;339:417–23.

- Nisbet-Brown E, Olivieri NF, Giardina PJ, Grady RW, Neufeld EJ, Sechaud R, et al.. Effectiveness and safety of ICL670 in iron-loaded patients with thalassaemia: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-escalation trial. Lancet 2003;361:1597–602.

- Cappellini MD, Cohen A, Piga A, Bejaoui M, Perrotta S, Agaoglu L, et al.. A phase 3 study of deferasirox (ICL670), a once-daily oral iron chelator, in patients with beta-thalassemia. Blood 2006;107:3455–62.

- Vichinsky E, Onyekwere O, Porter J, Swerdlow P, Eckman J, Lane P, et al.. A randomised comparison of deferasirox versus deferoxamine for the treatment of transfusional iron overload in sickle cell disease. Br J Haematol 2007;136:501–8.

- Taher A, El-Beshlawy A, Elalfy MS, Al Zir K, Daar S, Damanhouri G, et al.. Efficacy and safety of deferasirox, an oral iron chelator, in heavily iron-overloaded patients with beta-thalassaemia: the ESCALATOR study. Eur J Haematol 2009;82:458–65.

- Bennett JM, Catovsky D, Daniel MT, Flandrin G, Galton DA, Gralnick HR, et al.. Proposals for the classification of the myelodysplastic syndromes. Br J Haematol 1982;51:189–99.

- Greenberg P, Cox C, LeBeau MM, Fenaux P, Morel P, Sanz G, et al.. International scoring system for evaluating prognosis in myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood 1997;89:2079–88.

- Angelucci E, Brittenham GM, McLaren CE, Ripalti M, Baronciani D, Giardini C, et al.. Hepatic iron concentration and total body iron stores in thalassemia major. N Engl J Med 2000;343:327–31.

- Iron overload disorders among Hispanics–San Diego, CA, USA, 1995. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 1996;45:991–3.

- Araújo A, Drelichman G, Cançdo RD, Watman N, Magalhães SM, Duhalde M, et al.. Management of transfusional iron overload in Latin America: current outlook and expert panel recommendations. Hematology 2009;14:22–32.

- Penchaszadeh VB. Community genetics in Latin America: challenges and perspectives. Community Genet 2000;3:124–7.

- Penchaszadeh VB, Beiguelman B. Medical genetic services in Latin America: report of a meeting of experts. Rev Panam Salud Publica [document on the internet]. 1998, vol. 3, no. 6 [cited 2009 Oct 22]. p. 409–420. Available from: http://www.scielosp.org/scielo.php?script = sci_arttext&pid = S1020-49891998000600013&lng = en&nrm = iso

- Roldan A, Gutierrez M, Cygler A, Bonduel M, Sciuccati G, Torres AF. Molecular characterization of β-thalassemia genes in an Argentine population. Am J Hematol 1997;54:179–82.

- Loureiro MM, Rozenfeld S, Carvalho MS, Portugal RD. Factors associated with hospital readmission in sickle cell disease. BMC Blood Disord 2009;9:2.

- Cuéllar-Ambrosi F, Mondragón MC, Gigueroa M, Préhu C, Galactéros F, Ruiz-Linares A. Sickle cell anemia and β-globin gene cluster haplotypes in Colombia. Hemoglobin 2000;24:221–5.

- Adams RJ, McKie VC, Hsu L, Files B, Vichinsky E, Pegelow C, et al.. Prevention of a first stroke by transfusions in children with sickle cell anemia and abnormal results on transcranial Doppler ultrasonography. N Engl J Med 1998;339:5–11.

- Adams RJ, Brambilla D. Discontinuing prophylactic transfusions used to prevent stroke in sickle cell disease. N Engl J Med 2005;353:2769–78.

- Ballas SK. Iron overload is a determinant of morbidity and mortality in adult patients with sickle cell disease. Semin Hematol 2001;38:30–6.

- Vichinsky E, Butensky E, Fung E, Hudes M, Theil E, Ferrell L, et al.. Comparison of organ dysfunction in transfused patients with SCD or β Thalssemia. Am J Hematol 2005;80:70–4.

- Fung EB, Harmatz PR, Lee PD, Milet M, Bellevue R, Jeng MR, et al.. Increased prevalence of iron-overload associated endocrinopathy in thalassaemia versus sickle-cell disease. Br J Haematol 2006;135:574–82.

- Fung EB, Harmatz PR, Milet M, Balasa V, Ballas SK, Casella JF, et al.. Disparity in the management of iron overload between patients with sickle cell disease and thalassemia who received transfusions. Transfusion 2008;48:1971–80.

- Fernandes JL, Fabron A, Verissimo M. Early cardiac iron overload in children with transfusion-dependent anemias. Haematologica 2009;94:1776–7.

- Low LC. Growth, puberty and endocrine function in beta-thalassemia major. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metabl 1997;10:175–84.

- Gulati R, Bhatia V, Argarwal SS. Early onset of endocrine abnormalities in beta-thalssemia major in a developing country. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab 2000;13:651–6.

- Soliman AT, el-Zalabany M, Amer M, Ansari BM. Growth and pubertal development in transfusion-dependent children and adolescents with thalassemia major and sickle cell disease: a comparative study. J Trop Pediatr 1999;4591:23–30.

- Borgna-Pignatti C, Rugolotto S, De Stefano P, Zhao H, Cappellini MD, Del Vecchio GC, et al.. Survival and complications in patients with thalassemia major treated with transfusion and deferoxamine. Haematologica 2004;89:1187–93.

- Davis BA, Porter JB. Long-term outcome of continuous 24-hour deferoxamine infusion via indwelling intravenous catheters in high risk beta-thalassemia. Blood 2000;95:1229–36.

- Gabutti V, Piga A. Results of long-term iron-chelating therapy. Acta Haematol 1996;95:26–36.

- Adamkiewicz TV, Abboud MR, Paley C, Olivieri N, Kirby-Allen M, Vichinsky E, et al.. Serum ferritin level changes in children with sickle cell disease on chronic blood transfusions are non-linear, and are associated with iron load and liver injury. Blood 2009;114:4632–8.