Abstract

Background

The aim of this study was to evaluate the efficacy and safety of deferasirox in patients from Iran.

Methods

This was a retrospective, observational study in regularly transfused, iron-overloaded patients who received deferasirox 20–38 mg/kg/day for up to 12 months. Changes in serum ferritin were assessed as follows: from baseline to 3 months with deferasirox doses of 20–24 mg/kg/day; from 3 to 6 months with doses of 25–29 mg/kg/day; and from 6 to 12 months with doses of 30–38 mg/kg/day. The safety of deferasirox was evaluated monthly. Patients’ satisfaction with treatment was assessed after 9 months.

Results

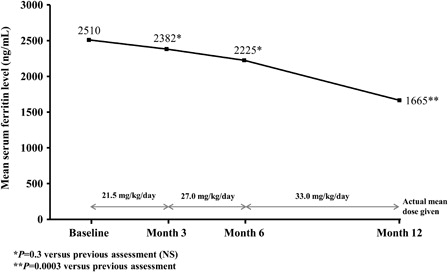

One hundred and nineteen patients were included. Overall mean serum ferritin levels were significantly decreased from baseline after 12 months of deferasirox therapy (2510 ± 1210 to 1665 ± 1240 ng/ml; P < 0.002). A significant decrease was observed once doses were increased to ≥30 mg/kg/day (P = 0.0003). Most adverse events were mild and observed at the dose of 20–24 mg/kg. Only one patient discontinued treatment. Around 90% of patients were satisfied with therapy.

Conclusion

This is the first study evaluating deferasirox in heavily iron-overloaded patients from Iran and confirms that deferasirox is effective and well tolerated; however, dose increases to ≥30 mg/kg/day should be considered if efficacy is insufficient.

Introduction

Blood transfusions are a routine treatment for patients with chronic anemia such as betathalassemia. However, cumulative iron overload is an inevitable consequence of regular transfusions and, if untreated, can lead to organ failure.Citation1 Supportive care with iron chelation therapy is therefore a mainstay of treatment in these patients, while hematopoietic stem cell transplantation is the only curative option.Citation2,Citation3 Deferoxamine (Desferal®; Novartis Pharmaceuticals, East Hanover, NJ, USA), which was developed more than 40 years ago, remains the standard chelation therapy for iron-overloaded patients with thalassemia in many countries worldwide. However, the use of deferoxamine is limited by its short half-life, which necessitates slow, continuous subcutaneous infusions 5–7 days every week. Deferiprone (Ferriprox®; ApoPharma, Toronto, ON, Canada) was the first oral iron chelation therapy to become available and is approved in Europe and other countries, including Iran. However, deferiprone is only indicated for patients with thalassemia when deferoxamine is contraindicated or inadequate and its use is further limited by a lack of well-controlled efficacy data and the occurrence of adverse events such as gastrointestinal symptoms, cytopenia, and arthropathy.Citation4,Citation5 Deferiprone is primarily administered in combination with deferoxamine,Citation6–Citation8 particularly in patients with cardiac iron overload.

Deferasirox (Exjade®, Novartis Pharmaceuticals) is a novel, once-daily oral iron chelator that was first approved in 2005 and is now available in more than 100 countries worldwide. Deferasirox is a tridentate ligand that binds iron (as Fe3+) with high affinity in a 2:1 ratio and has a half-life of 12–16 hours.Citation9,Citation10 The efficacy of deferasirox 20–40 mg/kg/day for the management of iron overload has been well documented in a number of clinical studies.Citation11–Citation16

The prevalence of thalassemia in Iran is high. Deferoxamine is the primary method for treating iron overload in Iran, and it is initiated when serum ferritin levels exceed 1000 ng/ml or when the patient has received 10–15 blood transfusions. Oral deferiprone has been available formally in Iran since 2003 and can be administered as monotherapy or combined with deferoxamine.Citation6,Citation17 Deferasirox has been available in Iran since November 2009. As poor compliance with deferoxamine remains one of the greatest limitations of iron chelation therapy, switching to an oral chelator is vital to ensure optimal management and improved quality of life for iron-overloaded patients with thalassemia. Deferoxamine and deferiprone are both available free of charge in Iran.

This is the first report of the efficacy and safety of deferasirox in transfusion-dependent patients with thalassemia from Iran.

Materials and methods

Study design and patient population

This was a retrospective, observational study evaluating deferasirox treatment in patients with transfusional iron overload; deferasirox was supplied by Novartis Pharma AG (Basel, Switzerland). Data were collected from patients at two major referral centers in Tehran (center of Iran) and Shiraz (south of Iran) from November 2009 to March 2011. All enrolled patients had serum ferritin levels ≥2000 ng/ml, including those diagnosed with beta-thalassemia major, beta-thalassemia intermedia, and sickle cell disease. Patients with betathalassemia intermedia were diagnosed after the age of 2 and received their first blood transfusion between 2 and 7 years of age. Patients with a history of non-compliance with treatment or the protocol (e.g. patients who were considered potentially unreliable and/or not cooperative), patients with positive viral hepatitis, systemic diseases including cardiovascular, renal, and hepatic disease, uncontrolled hypertension, mean alanine aminotransferase levels >300 U/l, history of ocular toxicity related to iron chelation, and pregnant or breastfeeding women were excluded from the study. The study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences and written consent was obtained from all patients.

Dosing and assessments

All patients received deferasirox doses of 20–38 mg/kg/day for up to 12 months. The treatment protocol was modified based on the achievement of ‘acceptable’ decreases in serum ferritin levels, which was measured in a fasting state using Enzyme Linked Fluorescent Assay (ELFA) technology (miniVIDAS® Automated Immunoassay Analyzer, bioMerieux, Marcy L'Etoile, France); ‘acceptable’ was defined as a decrease in mean serum ferritin of ≥500 ng/ml. Changes in serum ferritin were assessed at the end of each 3-month treatment period: from baseline to 3 months with deferasirox doses of 20–24 mg/kg/day; from 3 to 6 months with doses of 25–29 mg/kg/day; and from 6 to 9 months with doses of 30–38 mg/kg/day. Doses at the end of 9 months were continued until 12 months of treatment were complete. No patients had a fever, infection, or inflammation at the time of serum ferritin assessment. The frequency and severity of adverse events and biochemical parameters (including blood urea nitrogen (BUN), creatinine, liver enzymes, and urine protein/creatinine ratio) were evaluated monthly in all patients throughout the study. Patient satisfaction with therapy was assessed after 9 months of treatment by a valid and reliable questionnaire based on the cost of therapy, occurrence/severity of adverse events, and changes in serum ferritin level within an acceptable timeframe.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS 15 statistical software package (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± SD. Paired t -test was used to compare quantitative variables before and after different doses of deferasirox among patients. A P value of <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

In total, 119 patients (59 males and 60 females) were included; mean patient age was 19 years (range 2–35) and mean weight was 44.7 kg. One hundred patients had a diagnosis of beta-thalassemia major, 18 of transfusion-dependent betathalassemia intermedia, and one of sickle cell disease. All patients received blood transfusions every 2–4 weeks.

Efficacy of deferasirox

Overall mean serum ferritin level decreased significantly from 2510 ± 1210 ng/ml (median 2490; range 2120–13 000) at baseline to 1665 ± 1240 ng/ml (median 1560; range 1350–5100) after 12 months of deferasirox therapy (P < 0.002). Serum ferritin levels were relatively stable at doses of 20–24 and 25–29 mg/kg/day, but decreased significantly following escalation to 30–38 mg/kg/day (P = 0.0003; ). The efficacy response was similar in patients with thalassemia major and intermedia, as well as in the patient with sickle cell disease.

Safety of deferasirox

One hundred and eighteen patients (99%) completed 12 months of deferasirox therapy. One patient was excluded from the study at the end of initial 3-month treatment period due to a severe skin reaction (generalized maculopapular rash that was unresponsive to medical treatment or a decrease in dose). Thirty-four patients (29%) reported at least one adverse event during deferasirox treatment, although most were mild. Skin reactions (maculopapular rash) were reported in seven patients (5.8%), and one patient (0.84%) had a severe skin reaction that led to discontinuation when the patient was on dose of 20–24 mg/kg. Gastrointestinal adverse events (abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting) were reported in 14 patients (11.8%). Mild increases in liver enzyme levels were noted in eight patients (6.7%), although these were not considered to be clinically significant. Renal adverse events were reported in 10 patients (8.4%). Serum creatinine levels increased by <33% and urine protein/creatinine ratio increased by <0.6 from baseline in eight of these patients; these increases lasted for 3 months but resolved spontaneously without the need for treatment. Deferasirox therapy was interrupted for 1 month in one patient because of a urine protein/creatinine ratio >0.6, although treatment was restarted at a lower dose with no new renal adverse effects. Transient leukopenia was observed in one patient (0.84%).

There were no significant changes in BUN, creatinine, aspartate aminotransferase, and alanine aminotransferase levels after 12 months of deferasirox treatment ().

Table 1. Biochemical parameters before and after 12 months’ treatment with deferasirox

presents frequency of adverse effects based on different dosage of deferasirox. Most of adverse effects were seen at the dose of 20–24 mg/kg.

Table 2. Frequency of adverse effects of deferasirox on different dosage

Patient satisfaction with deferasirox

Seventy-nine patients (89.8%) stated that they were satisfied with deferasirox therapy and only nine (10.2%) were dissatisfied. Cost and delayed/inadequate reduction in serum ferritin levels (associated with the short treatment duration and insufficient dose for the extent of iron overload) were the most common reasons for patients’ dissatisfaction. Patients who had initially reported that they were not satisfied were re-evaluated once they had experienced a reasonable decrease in serum ferritin levels. The only remaining cause for dissatisfaction at this time was the cost of the drug.

Discussion

Deferasirox is a once-daily, oral iron chelator that is approved for the treatment of iron overload in transfusion-dependent patients. The clinical efficacy of deferasirox has been well documented in patients with various chronic anemias, including beta-thalassemia, sickle cell disease, myelodysplastic syndromes, and other disorders.Citation11–Citation16 The ESCALATOR study, which was conducted in patients from the Middle East, was one of the first large studies to demonstrate the efficacy and safety of deferasirox in patients with thalassemia who were unsuccessfully chelated with prior chelation therapy.Citation13,Citation18 Although deferasirox has been available in Iran for 2 years, this is a first report to specifically evaluate the efficacy and safety of this oral chelator in Iranian patients. In order to evaluate the most effective treatment doses for these regularly transfused and heavily iron-overloaded patients (baseline serum ferritin was >2000 ng/ml in all patients), the deferasirox dose was adjusted based on serum ferritin levels. After 3 and 6 months of treatment, there was no significant reduction in serum ferritin at doses of 20–24 or 25–29 mg/kg/day, respectively. Once the deferasirox dose was increased to 30–38 mg/kg/day, a significant decrease in serum ferritin was observed. These results suggest that patients with serum ferritin levels >2000 ng/ml (at least during the short time period evaluated in our study) have better responses with a deferasirox dose of ≥30 mg/kg/day. This is in agreement with previous studies that showed that doses of 25–30 mg/kg/day or higher are required to decrease serum ferritin levels and liver iron concentration in regularly transfused, iron-overloaded patients.Citation11–Citation16

Deferasirox treatment was well tolerated without any significant adverse events, with the exception of one patient who discontinued due to severe maculopapular rash. Transient gastrointestinal and renal adverse effects were most commonly observed in this patient population, which is in line with previous findings.Citation11–Citation16 The other important thing was in relation with different dosage as most of the adverse effects were observed at the dose of 20–24 mg/kg. The complications decreased with increase in dosage. It seems that tolerability of intake will be much better during time and adverse effects do not increase by dosage.

As observed previously,Citation19,Citation20 most patients in the present study (90%) were satisfied with the deferasirox therapy. However, some patients expected to see a rapid decrease in serum ferritin, which led to dissatisfaction when it did not occur.

As this is a confirmatory study of larger studies,Citation13,Citation16 the enrolled population is comparatively small. In addition, we acknowledge that serum ferritin may underestimate iron load in patients with thalassemia intermedia and that liver iron concentration is a more reliable measure in these patients.Citation21,Citation22 Nevertheless, we believe that these factors do not impact on the overall conclusions that we have made.

In conclusion, this is the first study evaluating deferasirox in iron-overloaded patients from Iran. The findings confirm those of previous studies regarding the efficacy and safety profile of deferasirox, and demonstrate the importance of optimal dosing strategies. Further detailed studies with lower serum ferritin levels and longer durations of treatment are warranted.

Authorship contributions

Mehran Karimi drafted the manuscript. Mehran Karimi, Azita Azarkeivan, Soheila Zareifar, Nader Cohan, Mohammad Reza Bordbar, and Sezaneh Haghpanah served as investigators on the trial, enrolling patients. They also contributed to data interpretation and reviewed and provided their comments on the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

Financial support for medical editorial assistance was provided by Novartis Pharmaceuticals. We thank Andrew Jones for medical editorial assistance with this manuscript. Also, we would like to thank Shiraz University of Medical Sciences for approving and supporting this study.

References

- Porter JB. Practical management of iron overload. Br J Haematol. 2001;115:239–52.

- Ramzi M, Nourani H, Zakernia M, Hamidian Jahromi AR. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for beta-thalassemia major: experience in south of Iran. Transplant Proc. 2004;36:2509–10.

- Ramzi M, Nourani H, Zakernia M, Dehghani M, Vodjani R, Haghshenas M. Results of hematopoietic stem cell transplant in Shiraz: 15 years experience in Southern Iran. Exp Clin Transplant. 2010;8:61–5.

- Cohen AR, Galanello R, Piga A, De Sanctis V, Tricta F. Safety and effectiveness of long-term therapy with the oral iron chelatordeferiprone. Blood. 2003;102:1583–7.

- Ceci A, Baiardi P, Felisi M, Cappellini MD, Carnelli V, De Sanctis V, et al. The safety and effectiveness of deferiprone in a large-scale, 3-year study in Italian patients. Br J Haematol. 2002;118:330–6.

- Zareifar S, Jabberi A, Cohan N, Haghpanah S. Efficacy of combined desferrioxamine and deferiprone versus single desferrioxamine therapy in patients with major thalassemia. Arch Iran Med. 2009;12:488–91.

- Galanello R, Campus S. Deferiprone chelation therapy for thalassemia major. Acta Haematol. 2009;122:155–64.

- Galanello R, Agus A, Campus S, Danjou F, Giardina PJ, Grady RW. Combined iron chelation therapy. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2010;1202:79–86.

- Nick H, Acklin P, Lattmann R, Buehlmayer P, Hauffe S, Schupp J, et al. Development of tridentate iron chelators: from desferrithiocin to ICL670. Curr Med Chem. 2003;10:1065–76.

- Piga A, Galanello R, Forni GL, Cappellini MD, Origa R, Zappu A, et al. Randomized phase II trial of deferasirox (Exjade®, ICL670), a once-daily, orally-administered iron chelator, in comparison to deferoxamine in thalassemia patients with transfusional iron overload. Haematologica. 2006;91:873–80.

- Galanello R, Piga A, Forni GL, Bertrand Y, Foschini ML, Bordone E, et al. Phase II clinical evaluation of deferasirox, a once-daily oral chelating agent, in pediatric patients with beta thalassemia major. Haematologica. 2006;91:1343–51.

- Porter J, Galanello R, Saglio G, Neufeld EJ, Vichinsky E, Cappellini MD, et al. Relative response of patients with myelodysplastic syndromes and other transfusion dependent anaemias to deferasirox (ICL670): a 1-yr prospective study. Eur J Haematol. 2008;80:168–76.

- Taher A, Elalfy MS, Al Zir K, Daar S, Al Jefri A, Habr D, et al. Importance of optimal dosing ≥30 mg/kg/day during deferasirox treatment: 2.7-year follow-up from the ESCALATOR study in patients with β-thalassaemia. Eur J Haematol. 2011;87:355–65.

- Cappellini MD, Bejaoui M, Agaoglu L, Canatan D, Capra M, Cohen A, et al. Iron chelation with deferasirox in adult and pediatric patients with thalassemia major: efficacy and safety during 5 years’ follow-up. Blood. 2011;118:884–93.

- Vichinsky E, Bernaudin F, Forni GL, Gardner R, Hassell K, Heeney MM, et al. Long-term safety and efficacy of deferasirox (Exjade®) for up to 5 years in transfusional iron-overloaded patients with sickle cell disease. Br J Haematol. 2011;154:387–97.

- Cappellini MD, Porter J, El-Beshlawy A, Li CK, Seymour JF, Elalfy M, et al. On behalf of the EPIC study investigators: tailoring iron chelation by iron intake and serum ferritin: the prospective EPIC study of deferasirox in 1744 patients with transfusion-dependent anemias. Haematologica. 2010;95:557–66.

- Karimi M, Johari SH, Cohan N. Attitude toward prenatal diagnosis for β-thalassemia major and medical abortion in southern Iran. Hemoglobin. 2010;34:49–54.

- Taher A, El-Beshlawy A, Elalfy MS, Al Zir K, Daar S, Habr D, et al. Efficacy and safety of deferasirox, an oral iron chelator, in heavily iron-overloaded patients with β-thalassaemia: the ESCALATOR study. Eur J Haematol. 2009;82:458–65.

- Cappellini MD, Bejaoui M, Agaoglu L, Porter J, Coates T, Jeng M, et al. Prospective evaluation of patient-reported outcomes during treatment with deferasirox or deferoxamine for iron overload in patients with beta-thalassemia. Clin Ther. 2007;29:909–17.

- Vichinsky E, Pakbaz Z, Onyekwere O, Porter J, Swerdlow P, Coates T, et al. Patient-reported outcomes of deferasirox (Exjade, ICL670) versus deferoxamine in sickle cell disease patients with transfusional hemosiderosis. Substudy of a randomized open-label phase II trial. Acta Haematol. 2008;119:133–41.

- Pakbaz Z, Fischer R, Fung E, Nielsen P, Harmatz P, Vichinsky E. Serum ferritin underestimates liver iron concentration in transfusion independent thalassemia patients as compared to regularly transfused thalassemia and sickle cell patients. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;49:329–32.

- Taher A, El Rassi F, Isma'eel H, Koussa S, Inati A, Cappellini MD. Correlation of liver iron concentration determined by R2 magnetic resonance imaging with serum ferritin in patients with thalassemia intermedia. Haematologica. 2008;93:1584–6.