Abstract

The h-index characterizes the publication achievement/impact of authors and is defined by the originator Jorge Hirsch as: ‘the number of papers with citation number ≥h’. The h-index has the inherent characteristic that authors with very different total citations can have the same h-index. In fact, no contributions to the h-index are made either by papers cited fewer times than h, or citations of an individual paper above h. Such citations are ‘excess’ citations not credited by the h-index. To address these deficiencies, we propose a simple, straightforward modification, the hb-index: , where h is the Hirsch h-index and e is the sum of all citations minus h2. Therefore, e is the excess citations not credited by the h-index.

Introduction

The h-index was first described by HirschCitation1 in an article entitled: ‘An index to quantify an individual's scientific research output’. The h-index was originally intended to be a measure of an individual's achievement although it commonly now is used as a bibliographic measure of impact. HirschCitation1 defined the h-index as ‘the number of papers with citation number ≥h’. The h-index has received acceptance and support,Citation2–Citation4 criticism,Citation5 corrections, complements, and a single-number alternative has been devised.Citation6. An extensive evaluation of the h index and its variants has been published.Citation7 The h-index and the related area of journal impact has recently been the subject of articles published in journals of higher education.Citation8,Citation9 The h-index has been used recently to assess impact of diseaseCitation10 and it has been scaled for different scientific fields that were shown to have significantly different average citations per paper.Citation11 The h-index can be calculated using databases such as Thompson Scientific Web of ScienceCitation12 or Google Scholar Citations.Citation13 A book and associated softwareCitation14 is useful generally for the subject of publication impact, specifically for analyzing academic citations, and for calculating the h-index.

Inherently, the h-index has the undesirable characteristic that individuals with very different numbers of citations can have the same h-index. Our goal in this report was to modify the h-index to express the differences resulting from increased total citations while maintaining the other attributes of the index that have been found useful in evaluating the publication impact of an individual including for promotion, tenure, asset allocation, and related administrative purposes.

Results

Every h-index can be generated by the minimum of hCitation2 citations when exactly h papers receive exactly h citations. The effect of hCitation2 citations justifies term in the hb-index. Also, any h-index theoretically could be generated by any total number of citations ≥h2. The greater than h2 citations are ‘excess’ citations and it appears reasonable and desirable to modify the h-index to credit these citations. This is especially important for young scientists who may have only a few papers and a comparatively low h-index. By analogy, it is desirable that a single-number index reveals the ‘ripening fruit’ whereas the h-index reveals only the ‘fully ripened’ fruit in one event as it creates a unitary increase in h on the special occasion that a citation occurs for a ‘nearly ripe’ paper.

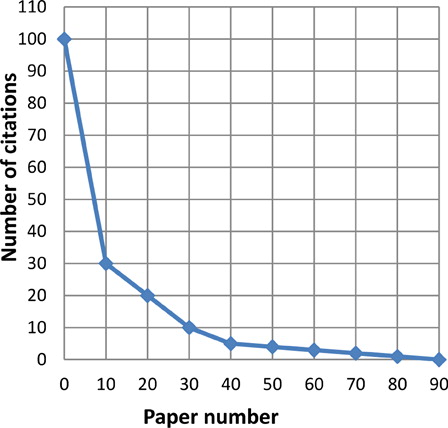

clarifies the h-index and reveals its limitation of not accounting for ‘excess’ citations. A specific publication record is shown for a hypothetical author who has published 90 papers cited 820 times. Citations are distributed as follows: 1 paper with 100; 9 papers each with 30; and groups of 10 papers each with 20, 10, 5, 4, 3, 2, 1, and 0 citations. By inspection, the h-index is 20 (number of papers with ≥h citations). However, the number of papers and their citation distributions are only one of many with the h-index of 20. Indeed, every h-index can be created from multiple distributions (except for the trivial case with one paper). also illustrates that no citations of a paper that exceed 20 make any contribution to the h-index of 20. Likewise, no citation of lowly ranked papers (those below the twentieth paper in this case) makes any contribution to the h-index (by definition, exactly 20 papers cited 20 or more times, creates the h-index). The other citations are ‘excess’ because they do not contribute to the h-index.

Figure 1. Graphic depiction for a hypothetical author with an h-index of 20 (see text for specifics).

There are other undesirable consequences of the h-index. For example, the first citation of any published paper of an individual creates an h-index of 1. However, the publication of any number of additional papers (however large the number) will not change the h-index until two papers become cited twice and (minimally) n papers must be cited n times for the h-index to become n. Thus, additional citations of ≤h for any number of papers cited h times will not raise the h-index. Also, a single paper, no matter how highly cited, cannot lead to an h-index that is larger than 1, and a body of papers, no matter how highly cited, cannot have an h-index larger than the number of papers in that body. Also, if a scientist publishes only one paper and that paper becomes cited any number of times, the h-index remains at 1. It is undesirable that an index behave in this manner.

compares the h-index and the hb-index. Publication records were created with different citation distributions to clarify the concept of ‘excess citations’ and to make the math simple enough to evaluate by inspection. However, other citation distributions contain the same defects. distributions A–F compare different authors with very different total citations but the same number of papers to isolate the effect of number of citations. For clarity, the excess citations for distributions A–H occur in papers with citations greater than h. It is obvious that publications with citations fewer than h have no effect on h.

Table 1. Corrective effects of the hb-index

Discussion

It is apparent () that many citation distributions can have the same h-index and number of publications but have unique hb-indices. The first row in has the fewest citations (hCitation2) for an h-index of 10 and it has zero ‘excess’ (e) citations. All citations contribute and the h-index and the hb-index are identical (the hb-index is ). The second row in also has an h-index of 10. However, the hb-index is

. Thus, the hb-index is increased, relative to h, by the contribution of the 90 citations that otherwise do not contribute. also shows that six authors, each with identical h-indices of 10 and exactly 10 papers but unique distributions of citations (A–F), have hb-indices that range from 10 to 31.21. Fundamentally, the h-index can never be larger than the total number of publications, but it can range downward to zero. The h-index precisely equals the total number of papers that are cited ≥h times. More specifically, as shown by citation distributions A–G (), once each paper has been cited a minimum of 10 times, the h-index becomes 10. Regardless of additional citations, the h-index remains at 10 until another paper is published and each of the now eleven papers is cited a least 11 times. These additional ‘excess’ citations are revealed and credited by the hb-index as the function

where e is the value of the ‘excess’ citations. Incorporating

provides a smooth increase in the hb-index.

To further compare the h-index with the hb-index, consider an additional case (not in ) with citations distributed identically to distribution B () except that all 90 excess citations are distributed among papers cited fewer times than the h index (10 in this case). This necessarily raises the total number of papers beyond 10 but these citations contribute nothing to the h-index. To evaluate the effects on the hb-index for this case, citations must be specifically assigned. Assume 10 papers with 10 citations each (to generate h = 10) and one paper each with the following number of citations: 9, 8, 7, 6, 5, 4, 3, 2, and 1. Now there are 19 papers with 145 total citations. The h-index remains 10 but the hb-index is now which equals 16.71 and credits the 9 papers that received a total of 45 citations. As a further example, if there had been 10 papers each cited 10 times and one paper cited an ‘excess’ 9 times, the h-index would, of course, be 10 but the hb-index would be

. Likewise, for 1 ‘excess’ citation, the hb-index would be

. The consequences for other cases are easily calculated.

It can be argued that the failure of the h-index to credit papers with citations below h is of low concern. However, researchers early in their careers are more likely to have such excess citations from papers not yet highly cited. Indeed, the hb-index recognizes this and gives appropriate credit based on the comparatively low (but significant for discriminating among authors) contribution of by lowly cited papers. However, when there are papers that receive many citations in excess of h ( distributions B–H; see footnote for specifics), these papers are appropriately highly credited by the hb-index which rises to comparatively large values because

is comparatively large.

Conclusion

The h-index is improved by calculating the hb-index which is the h-index plus a value with e defined as the excess citations (the citations in excess of the minimum total number (hCitation2) that can define the h-index). The hb-index credits citations that otherwise have no weight, differentiates among authors who have the same h-index, and is especially useful for distinguishing among publication records of young researchers with modest h-indices but significant papers that are ‘ripening’ but not yet highly cited.

References

- Hirsch J. An index to quantify an individual's scientific research output. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2005;102(46):16569–72.

- Spearman C, Quigley MJ, Quigley MR, Wilberger J. Survey of the h-index for all of academic neurosurgery: another power-law phenomenon? J Neurosurg 2010;113(5):929–33.

- Holden C. Random samples: data point-impact factor. Science 2005;309(8):1181c.

- Ball P. Index aims for fair ranking of scientists. Nature 2004;365:900–1.

- Kelly C, Jennings M. The h index and career assessment by numbers. Trends Ecol Evol 2006;21(4):167–70. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/1016/j.tree.2006.01.005 [accessed 14 April 2012].

- Bornmann L, Daniel H-D. What do we know about the h index? J Am Soc Infor Sci Tech 2007;58(7):1381–85.

- Bornmann L, Mutz R, Daniel H-D. Are there better indices for evaluation purposes than the h index? A comparison of nine different variants of the h index using data from biomedicine. J Am Soc Infor Sci Tech 2008;59(5):830–7.

- Budd J, Magnuson L. Higher education literature revisited: citation patterns examined. Res Higher Educ 2010;51(3):294–304.

- Bray N, Major C. Status of journals in the field of higher education. J Higher Educ 2011;82(4):479–503.

- McIntyre K, Hawkes I, Waret-Szkuta A, Morand S, Baylis M. The h-index as a quantitative indicator of the relative impact of human diseases. PLoS One [Electronic Resource] 2011;6(5):e19558.

- Iglesias J, Pecharroman C. Scaling the h-index for different ISI fields. Scientimetrics 2007;73(2):303–20.

- Thompson Scientific Web of Science. Available from: http://isiknowledge.com [accessed 14 April 2012].

- Google Scholar Citations [Internet]. Available from: http://scholar.google.com/citations?user=WOv4-EEAAAAJ&hl=en [accessed 14 April 2012].

- Hartzing A. [Internet]. The Publish or Perish Book. Melbourne, Australia: Tarman Software Research Pty Ltd; 2010, Available from: http://www.harzing.com/pop.htm [accessed 14 April 2012].