Abstract

Objective

The etiology and pathogenesis of hyperemesis gravidarum (HG) is still undetermined and has been suggested to involve oxidative stress. We aimed to evaluate the status of oxidative stress in HG by measuring the levels of total oxidant status (TOS), total antioxidant status (TAS), and by calculating the oxidative stress index (OSI).

Methods

In a case–control trial, fasting morning blood samples of patients with HG (n = 41) and healthy pregnant women (n = 39) were collected for analysis of serum TOS and TAS values as well as for calculation of OSI according to the formula: OSI = TOS / TAS × 100.

Results

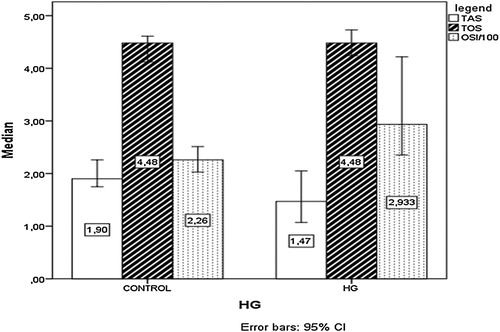

Serum TOS and TAS levels were similar in both groups. However, serum TAS levels were lower among HG patients compared to controls, which resulted in an increase in OSI (P = 0.025).

Discussion

The present study supports the role of systemic oxidative stress, reflected by an imbalance between the TOS and TAS, in patients with HG. Our findings distinguish the mechanism underlying oxidative stress to result from reduction of antioxidants rather than an increase in oxidants.

Introduction

Hyperemesis gravidarum (HG) is an uncommon disorder with intractable nausea and vomiting during the first trimester of pregnancy leading to fluid and nutritional deficiency, weight loss, electrolyte and acid–base imbalance, with an incidence of 0.3–1.5% of all pregnancies.Citation1,Citation2 This disorder may result in serious complications, including hepatic and renal impairment, Wernicke's encephalopathy, and even very rarely maternal or fetal death.Citation3–Citation7

The etiopathogenesis of HG is still unclear. To explain the etiology and pathophysiology of HG, there are hypotheses that include psychological, gastrointestinal, endocrinological, metabolic, infectious, immunological, and anatomical aspects.Citation8,Citation9

Oxidative stress can be described as an imbalance between oxidant substances (reactive oxygen species and antioxidant defenses) in living organisms. Oxidative stress has a role in various pathologic and physiologic conditions, including pregnancy and related complications.Citation10,Citation11

The relation between HG and oxidative stress has been evaluated previously but the results are conflicting.Citation12–Citation16 Previous studies reported that in the plasma of patients with pregnancy-related complications, superoxide dismutase, glutathione peroxidase, catalase activities, and non-enzymatic antioxidant levels are decreased, increased, or unchanged.Citation17–Citation20 Antioxidant activity has been shown to be statistically significantly higher in normal pregnancies compared to non-pregnant women. This augmented antioxidant activity was reported to continue to gradually increase throughout gestation.Citation21,Citation22 In normal pregnancies, an increased oxidative stress has been shown to be compensated by an increased antioxidant activity in serum.Citation23

We aimed to evaluate the status of oxidative stress in HG patients by evaluating the levels of total oxidant status (TOS), total antioxidant status (TAS), and the oxidative stress index (OSI).

Materials and methods

Forty-one consecutive pregnant women with HG and 39 healthy pregnant women as a control group who met inclusion criteria and consented to be included in the study were enrolled in this case–control study between August and December 2013. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (10# 24/07/2013). This study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki.Citation24 Inclusion criteria were: gestational age between 6 and 14 weeks, singleton pregnancy, persistent nausea and vomiting (>4 times per day), ketonuria >80 mg/dl in a random urine specimen, and electrolyte imbalance that requires intravenous replacement. Exclusion criteria were: multiple pregnancy, known thyroid disease, trophoblastic disease, eating disorders, known psychiatric disorder, smokers, women taking medication or having inflammatory disorders such as urinary infection. None of the women in the study or the control population had any kind of restrictive diet (gluten and lactose intolerance or vegetarian diet) before or during pregnancy. All patients were hospitalized for at least 24 hours for treatment. The control group consisted of uncomplicated pregnant women admitted for antenatal care at the same gestational age (6–14 weeks) who were also matched for parity with the study group. Gestational age was determined by crown rump length measurement in the first trimester of pregnancy in cases where there were more than 3 days difference between ultrasonographic measurement and the last menstrual period. Body mass index was obtained by dividing body weight in kilograms by the square of height in meters.

Blood sample collection

Blood samples were taken after an overnight fast in the early morning. All samples were immediately stored on ice at 4°C before centrifugation within at most 2 hours after collection, as described by Verit et al.Citation16 Centrifugation of the samples was performed at 4000 rpm for 10 minutes and the supernatant serum was separated and stored at −80°C until assay.

Measurement of TAS and TOS

Serum TAS and TOS levels were determined by the spectrophotometrical methods developed by ErelCitation25,Citation26 using commercial Rel Assay diagnostic kits (TAS lot no: RL030, TOS lot no: RL033, Gaziantep, Turkey). TAS had precision values lower than 3% and results were expressed as milimol Trolox Eq/l. TOS had precision values lower than 5% and results were expressed as micromol H2O2 Eq/l. Antioxidants in the sample reduced the dark blue-green-colored ABTS radical (2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid)) to the colorless ABTS form. The difference in absorbance at 660 nm is associated with total antioxidant level. Calibration of the assay was performed with a stable antioxidant standard solution (traditional Trolox equivalent) with a vitamin E analog. Ferrous ion–chelator complex is oxidized to ferric ion by oxidants that are present in the sample. Enhancer molecules in the reaction medium prolong the oxidation reaction. In an acidic medium, the ferric ion generates a colored complex with chromogen. Measurement of the color intensity spectrophotometrically is associated with the total amount of oxidant molecules that are present in the sample. Lastly, the assay was calibrated with hydrogen peroxide and the results are denoted as micromolar hydrogen peroxide equivalent per liter (μmol H2O2 Eq/l)

Determination of OSI

OSI is a marker for the degree of oxidative stress as a combined ratio between pro-oxidants (TOS) and antioxidants (TAS). The OSI value was calculated by the formula: ‘OSI (arbitrary unit) = TOS (μmol H2O2 Eq/l)/TAS (mmol Trolox Eq/l) × 100’, as previously reported.Citation27,Citation28

Statistical analysis

Distribution of the data was analyzed with Kolmogorov–Smirnov and Shapiro–Wilk tests. The data are presented as mean with standard deviation or median with minimum and maximum values of ranges for continuous variables, and as number with percentage for categorical variables. Data with a normal distribution were analyzed using the independent samples test. The Mann–Whitney U test and median test were used to analyze non-normally distributed data. The Chi-square test was used to compare categorical variables. A two-tailed P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. SPSS 21.0 was used for statistical calculations (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

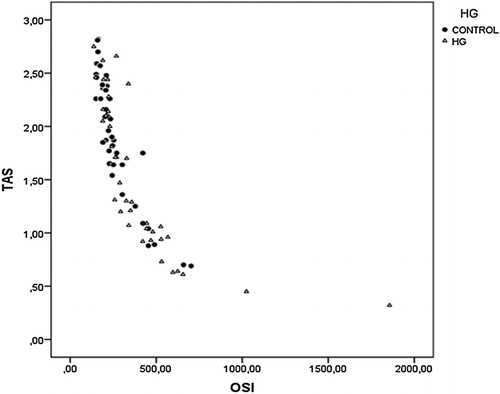

There was no significant difference in terms of age, gravidity, parity, and gestational week between the patients with HG and the controls (). There was no statistically significant difference between groups in terms of serum hemoglobin, hematocrit, white blood cells, platelet, serum glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase, serum glutamic pyruvic transaminase (SGPT), urea, creatinine, and thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) levels (). Serum TOS and TAS levels were similar in both HG and control groups. The OSI in HG patients was significantly higher compared to the control group (P = 0.025) ( and and ).

Table 1. Demographic data of the patients with HG and the control group

Table 2. Biochemical parameters of patients with HG and the control group

Table 3. Total antioxidant status, total oxidant status, and oxidative stress index of HG patients and control groups

To evaluate the potential effect of maternal-placental circulation and human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), the data were analyzed according to the gestational week. In the group of 6–10 weeks of gestational age, the TAS levels were significantly lower and OSI levels were significantly higher than the control group. But these differences were not significant in the group of 11–14 weeks of gestational age ().

Table 4. Total antioxidant status, total oxidant status, and oxidative stress index of HG patients and control groups at 6–10 weeks of gestation and 11–14 weeks of gestation

Discussion

The present study provides evidence in favor of increased systemic oxidative stress among patients presenting with HG, resulting from an imbalance between the TOS and TAS. The evaluation of serum TAS, TOS, and OSI values was able to distinguish the elements separately involved in oxidative stress. So far, various oxidant and antioxidant compounds in patients with HG have been evaluated.Citation12–Citation16,Citation29 Several laboratory kits with different methodology have been developed for the evaluation of oxidant reactive species, non-enzymatic molecules, and antioxidant enzymes.Citation12–Citation16,Citation29

Overall, studies with different serum markers have identified alterations of oxidant and antioxidant status in HG, although some conflicting results have been reported.Citation12–Citation16 Serum levels of TAS and TOS were investigated in patients with nausea and vomiting in only one recent study.Citation16 The investigators demonstrated that patients with HG had significantly higher TOS and lower antioxidant levels compared to controls. Likewise, we have found lower antioxidant levels, but no statistically significant difference was found between the study population and control group TAS levels. However, OSI was significantly different between the groups. When evaluating the conditions of oxidative stress, OSI is more unbiased and valuable compared to separate measurements of TAS and TOS since OSI shows the delicate balance between TAS and TOS more clearly.Citation30 Low serum TAS levels and similar serum TOS levels in HG patients cause the pro-oxidant⁄antioxidant balance to shift toward the oxidant side and this results in oxidative stress.Citation31 We conclude that this study presents more objective results than previous studies.Citation12,Citation15,Citation16

There is limited information related to the effects of antioxidant defenses on early human development. However, as the fetus is prone to free-radical damage during the period when major organ systems are developing, antioxidant status is particularly important. Previous studies reported antioxidant activity to be significantly higher among normal pregnancies compared to non-pregnant conditions.Citation21 Production of free radicals, which requires antioxidant activity to counteract it, has been shown to occur in normal placental tissues, where the enhanced antioxidant activity is needed to maintain a balance.Citation13,Citation32 It has been recently reported that oxidative stress plays a central role in the etiopathogenesis of RPL (Recurrent Pregnancy Loss).Citation33 In the present study, although statistically insignificant, lower antioxidant activity compared to healthy pregnant women was observed among patients with HG, which is in accordance with other studies.Citation3,Citation16,Citation34–Citation36

Steroid hormones, especially hCG, secreted during early pregnancy, seem to be responsible for symptoms of HG. Patients with HG have been reported to have higher hCG levels compared to controls and HG incidence increases with higher hCG conditions such as multiple and molar pregnancies.Citation37–Citation40 In one study, Xing et al.Citation41 found that oxidative stress stimulates the synthesis of different trophoblastic proteins, such as hCG and estrogens. In the present study, among the women at 6–10 weeks of gestational age, TAS levels were significantly lower in HG compared to the control group. After 11 weeks of gestation this difference was not present. Therefore, it can be speculated that increased oxidative stress in patients with HG at an early gestational age may be the reason for elevated hCG levels. On the other hand, starvation itself can also be the cause of oxidative stress. In other words, oxidative stress may be the result rather than the cause of HG.

Several theories have been proposed to explain the reason for decreased levels of antioxidants in HG. First, the decreased dietary intake of some nutrients rich in antioxidants is observed in women with HG.Citation42 Second, expression of antioxidant enzymes is decreased in HG patients.Citation15 Familial aggregation of HG may be related to genes associated with decreased antioxidant enzyme expression in patients with HG.Citation43

In conclusion, systemic oxidative stress may have a significant role in the etiology and pathogenesis of HG. HG patients should be evaluated for other diseases associated with oxidative stress. In the present study, we found that oxidative stress in HG is associated with reduction of antioxidants rather than with an increase of oxidants. Our results emphasize the therapeutic potential of antioxidant supplementation, which is becoming an increasingly used approach in treating the symptoms of women with HG.

Disclaimer statements

Contributors Saynur YILMAZ; corresponding author, drafting the manuscript, conception and design of study. A. Seval OZGU-ERDINC; acquisition of data, drafting the manuscript, analysis and interpretation of data. Canan DEMIRTAS; acquisition of data. Gulfer OZTURK; acquisition of data. Salim ERKAYA; final approval of the version to be published. Dilek UYGUR; article drafting and revising it critically for important intellectual content.

Funding None.

Conflicts of interest None.

Ethics approval The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (10# 24/07/2013).

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Peter Lemotte for revising the article as a native speaker.

References

- Lee NM, Saha S. Nausea and vomiting of pregnancy. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 2011;40:309–34, vii.

- Veenendaal MV, van Abeelen AF, Painter RC, van der Post JA, Roseboom TJ. Consequences of hyperemesis gravidarum for offspring: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BJOG 2011;118:1302–13.

- Chiossi G, Neri I, Cavazzuti M, Basso G, Facchinetti F. Hyperemesis gravidarum complicated by Wernicke encephalopathy: background, case report, and review of the literature. Obstet Gynecol Surv 2006;61:255–68.

- Di Gangi S, Gizzo S, Patrelli TS, Saccardi C, D'Antona D, Nardelli GB. Wernicke's encephalopathy complicating hyperemesis gravidarum: from the background to the present. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2012;25:1499–504.

- Eliakim R, Abulafia O, Sherer DM. Hyperemesis gravidarum: a current review. Am J Perinatol 2000;17:207–18.

- Latham PS. Liver diseases. In: Gleicher N GS, Sibai BM, Elkayam U, Galbraith RM, Sarto GE, (eds.) Principles and practice of medical therapy in pregnancy. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall International, Inc.; 1992. p. 960–9.

- Ismail SK, Kenny L. Review on hyperemesis gravidarum. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 2007;21:755–69.

- Verberg MF, Gillott DJ, Al-Fardan N, Grudzinskas JG. Hyperemesis gravidarum, a literature review. Hum Reprod Update 2005;11:527–39.

- Quinla JD, Hill DA. Nausea and vomiting of pregnancy. Am Fam Physician 2003;68:121–8.

- Wang YP, Walsh SW, Guo JD, Zhang JY. The imbalance between thromboxane and prostacyclin in preeclampsia is associated with an imbalance between lipid peroxides and vitamin E in maternal blood. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1991;165:1695–700.

- Biri A, Kavutcu M, Bozkurt N, Devrim E, Nurlu N, Durak I. Investigation of free radical scavenging enzyme activities and lipid peroxidation in human placental tissues with miscarriage. J Soc Gynecol Investig 2006;13:384–8.

- Onaran Y, Kafali H, Duvan CI, Keskin E, Celik H, Erel O. Relationship between oxidant and antioxidant activity in hyperemesis gravidarum. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2014 May;27(8):825–8.

- Fait V, Sela S, Ophir E, Khoury S, Nissimov J, Tkach M, et al. Hyperemesis gravidarum is associated with oxidative stress. Am J Perinatol 2002;19:93–8

- Aksoy H, Aksoy AN, Ozkan A, Polat H. Serum lipid profile, oxidative status, and paraoxonase 1 activity in hyperemesis gravidarum. J Clin Lab Anal 2009;23:105–9.

- Guney M, Oral B, Mungan T. Serum lipid peroxidation and antioxidant potential levels in hyperemesis gravidarum. Am J Perinatol 2007;24:283–9.

- Verit FF, Erel O, Sav M, Celik N, Cadirci D. Oxidative stress is associated with clinical severity of nausea and vomiting of pregnancy. Am J Perinatol 2007;24:545–8.

- Maseki M, Nishigaki I, Hagihara M, Tomoda Y, Yagi K. Lipid peroxide levels and lipids content of serum lipoprotein fractions of pregnant subjects with or without pre-eclampsia. Clin Chim Acta 1981;115:155–61.

- Walsh SW, Wang Y. Deficient glutathione peroxidase activity in preeclampsia is associated with increased placental production of thromboxane and lipid peroxides. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1993;169:1456–61.

- Agarwal A, Gupta S, Sharma RK. Role of oxidative stress in female reproduction. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 2005;3:28.

- Vidal ZE, Rufino SC, Tlaxcalteco EH, et al. Oxidative stress increased in pregnant women with iodine deficiency. Biol Trace Elem Res 2014;157:211–7.

- Hubel CA, Roberts JM, Taylor RN, Musci TJ, Rogers GM, McLaughlin MK. Lipid peroxidation in pregnancy: new perspectives on preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1989;161:1025–34.

- Fait V, Sela S, Ophir E, et al. Peripheral polymorphonuclear leukocyte priming contributes to oxidative stress in early pregnancy. J Soc Gynecol Investig 2005;12:46–9.

- Davidge ST, Hubel CA, Brayden RD, Capeless EC, McLaughlin MK. Sera antioxidant activity in uncomplicated and preeclamptic pregnancies. Obstet Gynecol 1992;79:897–901.

- World Medical Association declaration of Helsinki. Recommendations guiding physicians in biomedical research involving human subjects. JAMA 1997;277:925–6.

- Erel O. A novel automated method to measure total antioxidant response against potent free radical reactions. Clin Biochem 2004;37:112–9.

- Erel O. A new automated colorimetric method for measuring total oxidant status. Clin Biochem 2005;38:1103–11.

- Alp R, Selek S, Alp SI, Taskin A, Kocyigit A. Oxidative and antioxidative balance in patients of migraine. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2010;14:877–82.

- Karkucak M, Capkin E, Alver A, et al. The effect of anti-TNF agent on oxidation status in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Clin Rheumatol 2010;29:303–7.

- Verit FF, Erel O, Celik H. Paraoxonase-1 activity in patients with hyperemesis gravidarum. Redox Rep 2008;13:134–8.

- Esen C, Alkan BA, Kirnap M, Akgul O, Isikoglu S, Erel O. The effects of chronic periodontitis and rheumatoid arthritis on serum and gingival crevicular fluid total antioxidant/oxidant status and oxidative stress index. J Periodontol 2012;83:773–9.

- Yesilova Y, Ucmak D, Selek S, et al. Oxidative stress index may play a key role in patients with pemphigus vulgaris. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2013;27:465–7.

- Perkins AV. Endogenous anti-oxidants in pregnancy and preeclampsia. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2006;46:77–83.

- Yiyenoglu OB, Ugur MG, Ozcan HC, et al. Assessment of oxidative stress markers in recurrent pregnancy loss: a prospective study. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2014;289:1337–40.

- van Stuijvenberg ME, Schabort I, Labadarios D, Nel JT. The nutritional status and treatment of patients with hyperemesis gravidarum. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1995;172:1585–91.

- Welsh A. Hyperemesis, gastrointestinal and liver disorders in pregnancy. Curr Obstet Gynaecol 2005;15:123–31.

- Robinson JN, Banerjee R, Thiet MP. Coagulopathy secondary to vitamin K deficiency in hyperemesis gravidarum. Obstet Gynecol 1998;92:673–5.

- Fell DB, Dodds L, Joseph KS, Allen VM, Butler B. Risk factors for hyperemesis gravidarum requiring hospital admission during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 2006;107:277–84.

- Felemban AA, Bakri YN, Alkharif HA, Altuwaijri SM, Shalhoub J, Berkowitz RS. Complete molar pregnancy. Clinical trends at King Fahad Hospital, Riyadh, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. J Reprod Med 1998;43:11–3.

- Leylek OA, Toyaksi M, Erselcan T, Dokmetas S. Immunologic and biochemical factors in hyperemesis gravidarum with or without hyperthyroxinemia. Gynecol Obstet Invest 1999;47:229–34.

- Goodwin TM, Montoro M, Mestman JH, Pekary AE, Hershman JM. The role of chorionic gonadotropin in transient hyperthyroidism of hyperemesis gravidarum. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1992;75:1333–7.

- Xing Y, Williams C, Campbell RK, et al. Threading of a glycosylated protein loop through a protein hole: implications for combination of human chorionic gonadotropin subunits. Protein Sci 2001;10:226–35.

- Celik F, Guzel AI, Kuyumcuoglu U, Celik Y. Dietary antioxidant levels in hyperemesis gravidarum: a case control study. Ginekol Pol 2011;82:840–4.

- Zhang Y, Cantor RM, MacGibbon K, et al. Familial aggregation of hyperemesis gravidarum. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2011;204:230 e1–7.