Abstract

Archaeological filmmaking is a relatively under-examined subject in academic literature. As the technology for creating, editing, and distributing video becomes increasingly available, it is important to understand the broader context of archaeological filmmaking; from television documentaries to footage shot as an additional method of recording to the informal ‘home videos’ in archaeology. The history of filmmaking in archaeology follows innovations within archaeological practice as well as the availability and affordability of technology. While there have been extensive analyses of movies and television shows about archaeological subjects, the topic of archaeological film has been characterized by reactions to these outside perspectives, rather than examinations of footage created by archaeologists. This can be understood to fall within several filmic genres, including expository, direct testimonial, impressionistic, and phenomenological films, each with their own purpose and expressive qualities. Footage taken on site can also be perceived as a form of surveillance, and can modify behaviour as a form of panopticon. Consequently, there are considerations regarding audience, distribution, and methods for evaluation, as these films are increasingly available on social media platforms. This paper explores the broad context for archaeological filmmaking and considers potential futures for the moving image in archaeology.

Introduction

Notions of auteurshipFootnote1 have only recently come to archaeological practice; while there have been several analyses regarding archaeology’s relationship with the media, there have been relatively few explorations of media made by archaeologists, particularly that of videography (Clack & Brittain, Citation2007: 46; Piccini, Citation2009). This distinction, of ‘professional filmmakers who knew little about the process of archaeological investigation’ and ‘students trained in archaeology […] or on occasion the field directors Ruth Tringham and Mirjana Stevanovic’ (Tringham, et al., Citation2012: 39–41) producing films about archaeology is not necessarily a rigid divide (see also Earl, Citation2004; CitationPiccini, in press). The problem of professional vision (Goodwin, Citation1994), particularly the ability to ‘see’ archaeology and make evaluative judgements regarding the correct way to conduct and depict excavation, is a process that is difficult to quantify and present through videography, whether or not the person behind the camera is an archaeologist or a filmmaker.

While digital video recorders are increasingly ‘affordable and accessible’ (Van Dyke, Citation2006), specializing in digital media in archaeology arguably removes the archaeologist from excavation and from developing advanced field skills. The development of a ‘speciality’ within archaeology that is lab-based rather than excavation-based, such as palaeoethnobotany or micromorphology, requires the archaeologist to acquire skills outside of excavation. While acquiring a particular focus in addition to archaeological field skills is seen as important in post-graduate education and is vital for furthering archaeological understanding, such specialisms can be emphasized to the detriment of field skills. This seems to be more acutely felt by archaeologists who specialize in digital and visual media as their work is not perceived as ‘real archaeology’ (Perry, Citation2012). Expertise in both fieldwork and digital archaeology is exceedingly rare, though an ‘unprofessional’ video made by an archaeologist can speak to the current, low-fidelity, DIY aesthetic that is pervasive in online social media. Indeed, an unpolished video with minor editing can be seen as a more ‘authentic’ voice of a non-professional filmmaker; as Hanson and Rahtz (Citation1988: 111) state:

A professional production is not always necessary or desirable […] the Magnus Magnusson commentary for English Heritage’s film of Maiden Castle is perhaps less evocative of real archaeology than ‘punk video’ shot by an archaeologist on domestic format with a wave-about camera.

In this article I broadly address archaeological filmmaking in the United States and the United Kingdom. My focus is on footage filmed by archaeologists to better understand the practice of showing professional vision — archaeological seeing. I discuss what constitutes an ‘archaeological film’, then provide an overview of archaeology on film, from Dorothy Garrod’s excavations on Mt Carmel through the digital age. Drawing from ethnographic film methodology, I designate four genres within the medium: expository, direct testimonial, impressionistic, and phenomenological (cf. Barbash & Taylor (Citation1997), but see also Kulik (Citation2006) and Piccini (2014) for alternate approaches to typologies of film). I elaborate on these genres, identifying films within each, and discuss their relative utility in archaeological methodology. Following these genres, I consider the panopticon (Foucault, Citation1975) and film and other social media as surveillance on archaeological sites, and finally discuss the impact of social media on the creation and dissemination of archaeological film.

What is an archaeological film?

If finding a distinction between a professional and an archaeologist filmmaker can be problematic, the idea of a cohesive concept of ‘archaeological film’ is even more so. The productions that could arguably fall into the spectrum of archaeological film include excavation time lapses stitched together into movies to elaborately staged and costumed re-enactments. Content can vary immensely, from minimalist, experiential films that navigate the viewer through an ancient landscape to the intentionally didactic demonstrations of simple principles of excavation. This problem is raised in Archaeology on Film, wherein the authors state that ‘one of the main problems encountered in compiling the entries for this guide was determining what constitutes an archaeological film. Does it have to show excavation? Should it deal with prehistoric times?’ (Allen & Lazio, Citation1983: 2). In the second edition of the book, they follow much the same guidelines on what they had previously decided constituted an archaeological film — ‘explicitly archaeological, that treat excavations and archaeological methods, or that deal with the discovery, analysis, and interpretation of material culture’ (Downs, et al., Citation1993: 3).Footnote2

Previous analyses of archaeology in film evaluate popular movies (see Box Office Archaeology (Schablitsky, Citation2007), Archaeology is a Brand (Holtorf, Citation2007), A Treasure Hard to Attain (Day, Citation1997) and ‘Romancing the Stones: Archaeology in Popular Cinema’ (Hall, Citation2004)), while the relative measures of ‘truth’ and ‘reality’ may actually be greater in a cinematic feature than in a short documentary (Tringham, Citation2009), I exclude both popular movies and movies made by people who have no training in archaeology and do not consult with archaeologists from this analysis, concentrating on the more marginal films made by archaeologists. By omitting this large body of work, I hope to better discern the place of more informal videography in archaeological practice, though certainly some genres of archaeological filmmaking draw from familiar themes in popular movies. In my discussion of genres of archaeological film I move away from previous literature and intentionally exclude the popular documentaries wherein ‘archaeologists have very little control over the production and final editing’ and are used as on-location, talking-head experts by media companies (Schablitsky & Hetherington, Citation2012: 149). I also exclude works produced from ‘embedded’ artists who have no archaeological training, though the work of Janet Hodgson during her Artists in Archaeology training at Stonehenge is particularly of note, it is out of the purview of this article (Wickstead, Citation2009).

As such, I define an archaeological film as a film made by an archaeologist in order to communicate some aspect of archaeological research. These can include films that are not solely shot by archaeologists, but are edited or scripted by archaeologists. There are films made by archaeologists that could be considered professional, and are of high quality. Yet the most troublesome to categorize and the most interesting of footage shot by archaeologists is the latest iteration of archaeological film; snippets, and moments uploaded to social media websites such as YouTube, Facebook, Vimeo, and Vine. These short ‘films’ destabilize the boundaries between photographs and video, provide radical transparency through near-instantaneous updates, and provide a vibrant intervention into the archaeological record, further discussed below.

A short history of archaeology on film

The history of archaeological film and its social context deserves a much more thorough treatment than I can permit in this article; indeed, the early relics of archaeological film — grainy images, washed-out horizons, forgotten field hands — held me in such a thrall that it was difficult to stop watching old films and begin writing. Increasingly, these films have been posted online; Movietone and the British Pathe News Archive have excavation footage dating from the 1920s. A later example of footage of an archaeological excavation is documentation of Dorothy Garrod’s Mt Carmel 1931–33 seasons in the Peabody Museum film archives at Harvard University (Beale & Healy, Citation1975). A snippet of this film that was posted by the Pitt Rivers Museum to the social media video hosting service VimeoFootnote3 shows a faded, grainy, scene of indigenous workers hauling large buckets up a long ladder with impossibly unsafe working conditions; any details of the archaeology is lost to the impermanence of celluloid film.

A few clips of Louis Leakey’s 1931 expedition to Olduvai gorge were preserved in the 1974 film Search for Fossil Man, along with other reused footage from Chinese and Near Eastern sites. Early examples of archaeological film tended to ‘record on film a wide variety of dig life without any overall planning or purpose other than to show in a general way what life on a dig was like’ (Beale & Healy, Citation1975: 890). Aided by the development of the lightweight 35 mm Arriflex camera, archaeological news was regularly reported on early German newsreels, though these films during the 1930s and 1940s were heavily influenced by National Socialism (Stern, Citation2007: 203). The 1937 Shell Mounds in the Tennessee Valley produced by the Tennessee Valley Authority became one of the first widely distributed New World archaeological films, and the first to feature a soundtrack. Archaeological work in the Tennessee Valley was funded by the New Deal legislation passed by Theodore Roosevelt to alleviate the Great Depression (Lyon, Citation1996). Boon (Citation2008) links science documentaries and filmmaking during this time to improving national education and morale before and during the Second World War.

The complexity and variety of archaeological films continued to develop, and in 1944 the Ministry of Education commissioned Jacquetta Hawkes for an ‘unorthodox project’ — the creation of a film on British prehistory (Hawkes, Citation1946). The remarkable history of this wartime film is documented in part by Christine Finn (Citation2001), who notes the prevalence of the narrative of invasion as well as technological innovations such as the use of aerial shots. The film featured full reconstructions of structures as well as animated sequences, and in its aforementioned use of aerial photography is perhaps prescient in the current use of ‘fly-throughs’ in virtual 3D reconstructions as viewers are treated to a propulsive, forceful camera, full of movement, as the lens ‘slides down the walls of Cheddar Gorge and penetrates its caves to find the home of Palaeolithic man, it twists along a Skara Brae alley-way and ranges across one of the houses, it explores every corner of the Little Woodbury farmstead’ (Hawkes, Citation1946: 79).

Similarly, in the early 1950s in the United States, the Archaeological Institute of America set up a special unit to ‘produce a series of documentary feature length color films which will tell the story of the ancient world […] on a shoestring budget’ (Garner, Citation1954: 203). The hope was to ‘match the extremely high technical standards set by even the worst of Hollywood’s products’. Ray Garner, the filmmaker in charge of this unit, was particularly concerned with verisimilitude in battle scenes, as ‘the story of man cannot be told without battles’, and went into considerable detail describing how these films suggest battles using ‘huge thunder clouds sweeping over the mountains and plains to the north; trees and shrubbery beginning to move under a gradually increasing wind; a few boulders standing firm as the wind whips sand, twigs and pebbles unavailingly against them’ (Garner, Citation1954: 204). Yet he declares that ‘trick or “arty” effects […] should not be used for their own sake […] in order that the ancients may tell their own story, their works of art must be shown in as straightforward a manner as their condition will permit’. Finally, he states:

We believe in the motion picture. We believe that film skillfully blended with well written narration and fine music can render a great service to archaeology. The knowledge won by the patient labors of the scientist can be presented to the general public in a way which will make the ancients seem to live again. (1954: 205)

Broadly speaking, this positivism in visualization is well matched by the nascent processual mode of archaeology of the time.

Archaeologically themed broadcasting began on television in the United Kingdom in the 1950s. After the appearance of Sir Mortimer Wheeler, Stuart Piggott, and Sean O’Riordain on a television quiz show, the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) realized that ‘archaeology and archaeologists were not dull’ and produced several television series by telling ‘simple exciting stories about archaeological discoveries, processes, and problems’ (Daniel, Citation1954: 202). These early programmes were ‘popular beyond any reasonable expectation’ (1954: 203) and archaeological programmes have been featured on British television since that time. Certainly, Glyn Daniel was prescient in predicting the success of Time Team and National Geographic specials in stating that ‘the day may not be far distant when archaeologists will find their excavations and discoveries financed by commercial interests for TV programmes’ (1954: 205). In the United States this same period was marked by both an increase in the quantity of films about archaeology and by the dwindling participation of archaeologists (Vogt, Citation1955). As a result, ‘the visual portion in many of the films comes across as an impressionistic and not very informative supplement to the script, and is often poorly integrated with the script’ (Beale & Healy, Citation1975: 890). A notable exception to this is 4 Butte 1, a film highlighting processual research (Miller, Citation1972; Ruby, Citation1969). This was further remedied in the 1960s, after the Archaeological Institute of America formed a Committee on Films and Television and ‘detailed documentaries on specific excavation projects were becoming more common as field archaeologists began to work more closely with film editors and animators and even to make their own films’ (Beale & Healy, Citation1975: 890).

By the 1970s, archaeological film had become diverse enough in the United States to merit a small round of publications regarding useful titles for teaching archaeology (e.g. Beale & Healy, Citation1975; Cole, Citation1972; Floyd, Citation1970; Girouard, et al., Citation1973; Laude, Citation1970; Moulin, Citation1972). In 1983, the Archaeological Institute of America released Archaeology on Film, a book that contained reviews and details of archaeology films available in the United States (Allen & Lazio, Citation1983). In the second edition of the book, they mention a ‘significant change’ — that the dominant format of 16 mm film had changed to videocassette, making the films ‘accessible to all individuals with an interest in archaeology’ (Downs, et al., Citation1993: 1). Though the authors also identify the ‘advent of inexpensive video production and the proliferation of VCRs’ as problematic, as ‘the low cost of video production has resulted in a spate of new productions, not always of the highest quality’.

The formats available for archaeological filmmaking in 1993 are listed as 16 mm, VHS, ¾ in. U-matic, and Beta. Archaeology on television continued to develop, though was given a more prominent place on German and British airwaves (Piccini, Citation2007; Stern, Citation2007). Yet there was very little critical examination of these films; it was not until Angela Piccini’s (Citation1996) discussion of the construction of Celtic people in documentaries that questions of the ‘how and why and for whom film has been used to construct and reconstruct images (in this case) of a pan-European Celtic warrior aristocracy’ (1996: S91) were raised. The lack of engagement of academics with television has been blamed on ‘snobbery’ by Amy Ramsay, in her dissertation regarding archaeology and television (2007). She cites the television show Time Team, which ran from 1994 to 2012 on Channel Four in the United Kingdom,Footnote4 as having a ‘substantial impact on the field of archaeology in Great Britain’ (Ramsay, Citation2007: 48).

The move from analogue to digital video happened quietly in archaeology; while digital video was introduced commercially in 1986, it was not until the early 1990s that home computers had the ability to manipulate these videos. The transition to digital video has created a great deal of anxiety in both photography and cinema; while one of the central issues in photography is a loss of veritas, in film the change from analogue to digital is framed within aesthetics and sensuality (Rodowick, Citation2007). This change has not been noted at all in archaeology, besides the shift in technology making videography more accessible to archaeologists. In the early 1990s, systematic video recording was mentioned as useful in archaeological excavation as a way to have a ‘more complete, affordable visual record’ in contrast to photography (Stone, Citation1991: 41), though the format that is suggested by Stone for archival purposes, videodiscs, is already obsolete. Still, the 1990s and 2000s saw a proliferation of archaeological film; a nexus of greater availability of technology, near instantaneous distribution, and increased participation in archaeological moviemaking, have produced a wide-open field.

Genres in archaeological films

There are relatively few publications regarding the creation of archaeological films by archaeologists; while several excavation reports may mention the existence of footage of the excavation, this footage is often unavailable and unedited. The initial outlay for a video camera, microphones, DV tapes, and increasingly SD cards, are obvious costs that are easily accounted for in an excavation budget, yet the subsequent time and editing equipment required to process the footage can be more difficult to calculate as skill can vary among filmmakers. The progression from analogue to digital film has brought some of the costs associated with video production down and removes the need for specialist equipment (beyond a high-powered computer and software) to edit footage on site (Tringham, et al., Citation2012). Like photography, videography on archaeological projects is a versatile tool that can be used to record formal and informal events during fieldwork. Though one of the affordances of digital videography is the ability to take much more footage, the time required to edit this footage is still substantial. The experience of wading through hours of film that were not taken with a clear purpose or that lack a clear subject to find useable footage is a valuable lesson in filming with a vision or an idea of the final project. This does not imply rigidity in subjects deemed worthy of recording, as opportunistic, extemporaneous footage can improve the evocative quality of film projects. On large excavations, a process for recording both formal and informal events develops over multiple iterations of fieldwork through feedback from the rest of the team (Brill, Citation2000; Nixon, Citation2010).

Though the initial capture of film can dictate later media outputs to a certain extent, most media can be ‘remixed’ to serve any purpose. Footage that was initially captured to illustrate the surrounding landscape of a site could be repurposed to use as part of a video-tour of the site, or as part of an exposé on the farming practices that are draining the water table and jeopardizing the archaeological remains. Archaeological work could be portrayed as serious, intensive labour, or, in the case of a time-lapse video taken at Çatalhöyük, begin with the meticulous excavation of a wall on site and end in a Benny Hill parody.

This ability to repurpose archaeological video reflects Bolter and Grusin’s concepts of Respectful and Radical Remediation (2000). Most remediation of archaeological information is respectful, ‘without apparent irony, critique, manipulation, or challenge in the mediation’ (Tringham, et al., Citation2007). Radical remediation — critical, self-referential re-uses of media that de-centres the original subject — has been relatively rare in archaeological media, but are increasing in number as archaeologists continue to experiment in film. This experimentation is encouraged by the affordances of digital film and by the increased recognition and distribution available to archaeologists through the Internet.Footnote5

There have been several efforts to classify archaeological films. An early recognition of genres in archaeological film include Casper Kraemer’s (Citation1958) analysis of the eleven films assembled by the Archaeological Institute of America, dividing them by their purpose: inspirational, educational, interpretive, documentary, and training films. Jean Laude (Citation1970) simply divided archaeological films by audience: those for professional archaeologists and those for students and general audiences. Beale and Healy (Citation1975) categorize the films by subject matter, stating that there are five types: excavation or laboratory methodology films, single-site documentaries, syntheses dealing with whole regions or civilizations, films which focus upon a single problem, and experimentalFootnote6 or ethnographic studies. In her examination of British Television, Kulik (Citation2006) finds six representational styles: backstage, detective, expository, essay, how-to, and reconstruction. Finally, while ‘genres’ is perhaps a strong word for similarities found between these films, and there are certainly videos that incorporate more than one of these themes, a new categorization that acknowledges the unstable categories of our visual grey literature as well as our more formalized films provides a more comprehensive view of film in archaeology. The genres that I discuss include the categories of expository, direct testimonial, impressionistic, and phenomenological films, which will be defined below. As such, I identify previously marginalized videography and the increasingly experimental archaeological films, as well as the utility of more traditional narrative forms.

Expository

Most of the videos used to teach archaeology or for public outreach are in the more traditional, stand-alone, didactic expository style of documentary, using ‘voice-of-god narration’ and expert interviews (see Bruzzi, Citation2000; Nichols, Citation1991), or ‘respectful remediations’ (Bolter & Grusin, Citation2000). These videos use varied footage to produce a cohesive storyline about an archaeological subject. While there are usually ‘talking head’ interviews from archaeologists, the content of these interviews is generalized commentary on the site. Both archaeologist filmmakers and non-archaeologist filmmakers produce these films that are ‘popular among television programmers because it presents its point of view clearly’ (Barbash & Taylor, Citation1997: 18–19). Though the videos produced by archaeologists do not follow the same ‘popular clichés’ that emphasize ‘exotic locations, adventurous fieldwork and spectacular discoveries’ (Ascherson, Citation2004; Holtorf, Citation2007: 33), these films often do follow narratives of discovery and feature long shots of the landscape set to genteel flute music. Ruth Van Dyke (Citation2006: 371) describes In the Shadow of the Volcano:

The film begins with vaguely exotic music, evoking the romantic and culturally distant past. Still and moving images are shown of past and present archaeological sites and landscapes. Archaeologists are depicted at work, but from an objectifying distance. Information is provided in voiceovers presented in the authority-laden tones of an unidentified, deep-voiced, male narrator.

Expository films have fallen out of favour in anthropological documentary filmmaking (Barbash & Taylor, Citation1997), but they persist in archaeology. They are incredibly useful as a way to communicate information about finds and periods being investigated through the archaeological process. In order to form a narrative regarding the archaeological process, the filmmaker must broaden their view of the site, negotiating the intense focus that is required during fieldwork while keeping the ‘storyline’ in mind. Expository films can be an entry into a broader realm of film genres; after putting together a successful visual narrative and learning the basics of capturing footage and editing video, the filmmaker can carry that confidence into more experimental forms.

Making a video enters the archaeologist into a conversation about stakeholders, potential audiences for the film, and the extent that the archaeologist wants to bring others into creating a narrative about the site. Lucia Nixon notes that the most interesting thing about making an archaeological film is that it ‘can bring out issues that were there all along’ (2010: 331). Nixon’s film about the Sphakia survey in Greece ‘raised important intellectual and ethical issues’ after she realized that she had not considered showing the film locally in Greece, but only had showing the film to her students back in Canada in mind. Expository films can be more accessible to broader audiences, and allow archaeologists to tell their own stories in contrast to clichéd popular media accounts.

As a corollary to expository films in archaeology, a few filmmakers have turned the concept of the straightforward documentary on its head by making and studying ‘mockumentaries’. These mockumentaries are a form of ‘recombinant history’, skewering concepts of truth and fiction in the archaeological record as a form of critique of both the expository style of filmmaking and the construction of dominant narratives in archaeology (Tringham, Citation2009). In studying the reception of accuracy and truth in television documentaries with segments of re-enactment, Angela Piccini cites Annette Hill’s conclusion that viewers ‘believe the drama more than the documentary’ (Citation2007: 228) while recommending a re-examination of authenticity in presenting archaeological information. Mockumentaries can be a way to signal to viewers that truth is often subjective in documentaries, providing insights into the process of knowledge construction in archaeology. Ruth Tringham identifies Jesse Lerner’s Ruins: A Fake Documentary as an example of a mockumentary about colonialism in the construction of pre-Hispanic history of Mexico (Tringham, Citation2009). She cites Steve Anderson’s analysis of Ruins as showing how ‘Lerner gradually erodes the authority of the archaeologists’ and historians’ objectivity’ (Tringham, Citation2009). The utility of mockumentaries can be summed up in Anderson’s statement:

By the end of Ruins, a senile old history has essentially been replaced with a smarter, newer one. The difference is that Ruins functions as an open rather than a closed text — a text that suggests fissures and contradictions in its own argument and ultimately stretches beyond the critique of historiography to pose an indictment of tourism, colonialism, ethnography, and documentary itself. (Citation2006: 82)

Direct testimonial

Today is August 5th, 2008, and you are in Building 49, space 335, this is feature 1651 and what we’ve done here is reveal a series of paintings on the south-facing wall of this platform.

In the direct testimonial, the archaeologist provides a summary of current finds and conditions on site. At Çatalhöyük these videos are sometimes called ‘phase videos’, as they are performed at the end of a building phase or during an important discovery. On some excavations, the short films are called ‘video diaries’ and are an account of a period of time on the excavation. While some of the videos are simple, linear accounts describing the archaeology, some intersperse footage into the dialogue with direct views of the particular feature the archaeologist is speaking about. In their excavations at Wharram Percy and Elginhaugh, Hanson and Rahtz (Citation1988: 111) cite the utility of ‘the visual excavation diary, with talk-over, as an aide-memoire’. Archaeological video diaries are likely to have followed the practice of site tours, during which the archaeologists would relay information about the stratigraphy and any interesting finds to the rest of the team or to visitors on site. This expository, performative narrative is a form of ekphrasis, verbally telling the visual story of the stratigraphy in a short monologue while other team members and visitors look on from the side of the trench. These ekphrasic episodes are occasionally filmed during the site tour, but many video diaries feature the excavator alone in the trench, speaking directly to the camera, with no audience other than the camera and filmmaker.

The direct testimonial is arguably the most authoritative form of archaeological video; the trench supervisor gives their interpretation to the camera and there is no discussion or alternative presentations to de-centre this interpretation. However, these videos defy easy categorization. On face value, the direct testimonial is an example of the expository documentary style, as the narrator ‘address(es) the spectators directly, through either an on-screen commentator or a voice-over track’, ‘seek(s) to inform and instruct’ and ‘leaves little room for misinterpretation’ (Barbash & Taylor, Citation1997: 17–19). Yet the narrator is not removed from the action or the scene, but is directly interacting with the materials they are describing. The ekphrasic narrative relies on the participation of the archaeologist in the landscape. While the video is an authoritative monologue of interpretation, the setting is intimate, and the filming usually occurs from an unprivileged camera height, at the level and angle that would realistically reflect the position of the filmmaker. Unprivileged camera position asserts that ‘filmmakers are human, fallible, rooted in physical space and society, governed by chance, limited in perception — and that films must be understood this way’ (MacDougall, Citation1997: 203).

In a direct testimonial, the authorship of the interpretation of the archaeology (if not the video) is transparent. The videos are not considered a legitimate final publication format and the archaeologists explaining the site stratigraphy will have to re-explain it in written form. Generally, video diaries are not a stand-alone source, but are embedded in a contextualizing website or have a description giving the broader context of the site. The direct testimonial is a unique example of a practice that articulates with the storytelling aspects of field archaeology, creating a niche genre of media within archaeology. While the power of images in archaeological photography and their non-reflexive use as a form of scientific proof has been challenged (Shanks, Citation1997), the direct testimonial requires the author of the interpretation to explain the stratigraphy as part of the visual production; the image does not retain all authority and neither does the archaeologist, but the meaning is made in concert by the performance that is captured on video, embedded in the landscape.

Impressionistic

Increasingly archaeologists have begun to experiment with impressionistic documentaries, documentaries that are ‘lyrical rather than didactic, poetic rather than argumentative’ and that ‘imply more than they inform, and evoke more than they assert’ (Barbash & Taylor, Citation1997: 20). Though a relatively small number of these films are made, they specifically investigate the interdisciplinary space between art and archaeology, emphasizing that ‘through this hybrid space, sensibilities from art and archaeology have the potential to inform each other in ways that not only broaden our range of expression but also push our practical and theoretical practice in new and exciting directions’ (Witmore, Citation2005: 57, see also Bailey, et al., Citation2009).

The lines between impressionistic and expository documentaries are not always obvious. For example, Skeuomorphs (see ), about the investigation of the knapped glass points made by Ishi that are housed in the collections of the Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology, California, is completely without diegetic sound but is otherwise a straightforward expository narrative. However, in the middle of the film, as I examine the materiality of the glass by otherwise scientific means of quantifying the length and width of Ishi’s points, the film enters an impressionistic montage of glass colours and forms. This montage emphasizes the hybridity of Ishi’s practice — what was viewed as an ‘ancient’ skill set was performed with ‘modern’ materials, and this fascinated Ishi’s audiences as he knapped at the museum, and continues to intrigue the public today, as collections of glass points can be found in museums around the world (Heizer & Kroeber, Citation1981).

Impressionistic documentaries in archaeology are more common among post-processual archaeologists, as they celebrate subjectivity and lack the authoritative voice-overs and overtly didactic structure of the expository film, yet these films are sometimes confusing and frustrating to audiences expecting tidy narratives about the past (Barbash & Taylor, Citation1997). Yet some archaeological filmmakers are able to create compelling impressionistic documentaries that capture the multiple and fragmentary nature of archaeological research. For example, In Transit, an impressionistic video about the ‘excavation’ of a 1991 Ford transit van, it was decided that ‘the screen-work would be self-analytical’ a ‘Greek chorus’ of unidentified voices would be arranged almost as if in conversation to contest a more conventional, linear, visual narrative’ with the dialectic emerging ‘only at the last creative moment’ (Bailey, et al., Citation2009: 18). While the film does follow a linear progression following the investigation of the van, the quick jump cuts between the shots, combined with the un-credited, disjointed voices create an aestheticized account of archaeological investigation. In the case of In Transit, the impressionistic format of the film reflects the progressive, contemporary stance of the archaeologists conducting the research.

Phenomenological

Phenomenological archaeological film is concerned with granting the viewer the gaze of an archaeologist. Filmed at eye-level, the video attempts to convey the sense of landscape and place. Through the camera’s lens she views the physical landscape of the archaeological site in the foreground and middle ground, the excavations in progress, the colours and textures of the soil, layers of clearly defined strata, artefacts in the sidewalls, and the buzz of conversations. She takes in the background as she moves around the site, the views of expansive, fresh-cut hayfields, the surrounding waterways, a bright blue sky, the impressive historical mansion (Ryzewski, Citation2009).

The archaeologist is using the video camera to record the sensory components of archaeological fieldwork, the sounds and sights ‘afforded by screen and microphone that cannot be conveyed or reproduced in the written narratives or archival photographs’ (Ryzewski, Citation2009: 363). This use of ‘phenomenological’ to describe this genre of film does not reflect Allan Casebier’s (Citation1991) use of the term phenomenology to describe the relationship between the film and the viewer of the film, but rather Vivian Sobchack’s emphasis on the subjective, emotional, and existential side of the film (Sobchack, Citation1991; Wahlberg, Citation2008). Still, phenomenology in film criticism is generally used to describe the relationship of the viewer of the film to the film, not the intention of the maker of the film. This understanding of phenomenological film in archaeology is within the actions of the filmmaker conveying their sense of place as directly as they understand it, to the viewer. This may be problematic in uncritically reproducing the archaeologist’s gaze. In contrast to the observational styleFootnote7 of documentary film, phenomenological archaeological films do not adopt the same film codes of fictional films; they are primarily shot from the perspective of the archaeologist, in a single, continuous shot. A particularly evocative example of a phenomenological film is Guttersnipe by Angela Piccini (Citation2009), which follows the line of a drain in Bristol, tracing the material remains and subtle changes through an expressive monologue.

Much of the ‘punk’ footage of archaeological excavations is phenomenological, though a better term for it may be ‘experiential’ or ‘incidental’. Video cameras in mobile phones provide the ability to take short films and post them online immediately, enabling archaeologists to share the on-site experience. A photograph taken of a dust plume is certainly evocative, but while excavating in Qatar, a short video was the only medium that could capture the ferocity that had blown onto site. Sometimes these phenomenological moments are inserted into longer expository or impressionistic films, but often their powerful diegetic sound is lost in voice over. Some of the on-site discussions between specialists and excavators as well as lab and excavation work were filmed at Çatalhöyük in short clips that were stored on the on-site database (Hodder, Citation1997). These moments were captured to show the interpretive process, though at the time of publication they are unavailable to the public. These short, phenomenological videos compare favourably to ‘home movies’ or ‘folklore documentary’ (Sherman, Citation1998).

A formalized form of the phenomenological film is the video walk, or what Witmore (Citation2004a) terms, ‘peripatetic video’. This form of media requires the viewer to be in the same place as the videographer, holding a device that replays the previously shot video as the viewer walks around wearing headphones. Witmore draws inspiration from media artist Janet Cardiff’s video walks that create a ‘media overlay whereby the digital media are superimposed upon the corporeal background’ (Citation2004b: 61). Witmore created his videos at four sites in Crete, incorporating surface garbage on a Peak Sanctuary and a funeral service in the Old Town of Rethymnon. Along with diegetic sound he incorporates ‘sounds evocative of past events, such as the clank of armor in battle or the roar of WWII machine guns in the distance’ and ‘contextual descriptions including […] notebook entries from excavation reports’ (2004b: 64) and discussions about other scholarship or feelings about the place. The Senses of Place project at Çatalhöyük was also inspired by Janet Cardiff’s video walks. However, instead of the viewer of the video walk being locked into a single route, CitationTringham, et al. (2009) allowed the viewer to choose their own route, ‘remixing’ their experience with the media provided.

These categories, or sub-genres of archaeological films — expository, direct testimonial, impressionistic, and phenomenological — do not comprise the entirety of the canon, and many works intermix modes of videography. Still, these assignations leave more room for experimental films that would have been uncategorizable under earlier classification schemes. It is likely that digital media will allow even greater variety in the near future, such as augmented reality films and machinima — films made entirely within virtual worlds. Even now, the file size for animated GIFs can be larger with increased Internet download speeds, effectively creating short films that defy easy categorization. Still, the aforementioned categories make the experimentation in archaeological film more visible; it is probable that the archaeologist who takes a video on her iPhone to upload to Facebook might not assign such great import to her actions. But being aware of a larger lexicon of filmmaking and of the genres of archaeological films allows us to contextualize her video and query the nature of the archaeological archive.

Archaeological video and the panopticon

Working on large archaeological projects is often like living in a fishbowl, and this was especially true at Çatalhöyük (Ashley, Citation2004). When we were not being watched by the daily site visitors, there would be specialists or guards, and sometimes artists or anthropologists would wander through. This feeling of being watched was especially true when videographers or people recording sound would come on site without warning. It was disconcerting to look up and realize that you were being filmed. Chadwick (Citation2003: 103) and his colleagues ‘found the cameras at Çatalhöyük intrusive’. The availability of inexpensive video allowed a more casual use of filming around the site, and the zoom lenses and directional microphones allowed videographers a false proximity to excavators who may not have been aware that their actions and conversations were being captured and subsequently used without their knowledge or permission. Even video that was taken with permission was rarely shared with the interviewees. After conducting one such video interview with Roddy Regan, a long-time archaeologist at Çatalhöyük, he gave me a direct look and said, ‘I’ve filmed hundreds of these [interviews] but I’ve never ever seen any of the results’.

Surveillance is deeply implicated in the lineage of new media. Lev Manovich (Citation2001) traces the history of the computer screen from photography, through radar, and then the development of tracking software by the Semi-Automatic Ground Environment (SAGE) command centre that controlled US air defences in the mid-1950s. With nearly instantaneous online publication available for videos, there is the potential for embarrassing or inappropriate content to become widespread before the subject of the film can take control of the content. This behaviour is relatively innocuous compared to the notorious, ubiquitous tracking of social media companies who use and sell data about users’ interests and interactions with friends (Boyd, Citation2011). Yet there are ‘discriminatory social implications of panopticonism’ that reveal the differential social status of those under scrutiny and those who hold the cameras (Elmer, Citation2003: 232). While this has abated somewhat in light of the growing availability of video cameras, there still remains a certain wariness of archaeologists toward filmmakers.

Film is not the only means to surveil the members of excavations; mandatory site diaries or blogs can be framed as a reflexive measure yet without reciprocity throughout the team and an explicit assurance that they will not be used against the individuals who express their opinions, the blogs quickly become dry accounts of stratigraphy. To remedy feelings of surveillance while taking photographs and videos on site there should be a relationship of trust that the filmmaker would not abuse, by videotaping while the subject was unawares, nor would they publish any media without the permission of the subject. Issues of assent and Human Subjects Review in regard to video are out of the purview for this article, yet it is relevant to note that feelings of surveillance can be mitigated by the position of the filmmaker within the team. If the person is another archaeologist or a long-trusted site media expert, there is an intimacy and trust present in the media creation process that can be absent in media made by outsiders.

The audience and social media

It is telling that Laude (Citation1970) divided archaeological films by their intended audiences, those made for professional archaeologists and those made for students and general audiences. The films that are made for other archaeologists posit a certain amount of archaeological training and background; in particular, direct testimonials address the archive writer, the director, the specialist who is interested in the particulars surrounding a phase, feature, or artefact of note. But most archaeological films are for a more general audience, though this audience is not usually articulated in terms of specific groups of stakeholders. In Tringham’s (Citation2009: 11) introduction to the Archaeological Film Database, she identifies a need to critically evaluate both the audience’s interaction with the film and the socio-cultural impact that the film may have. Reviewers of films must ‘think about how an audience at the time when the movie was made might have made sense of the movie and how this would be different from the response of current viewers’.

Still, there are very few published attempts to quantify audience response to archaeological films. One example is the work of Marilyn Beaudry and Ernestine Elster who held an archaeological film festival, during which they screened films at the University of California, Los Angeles, and the University of California, Riverside, drawing crowds of 200 and 50, respectively. They prepared a questionnaire to establish the audience profile of the film festival and published their responses. The audience had a majority of women (UCLA, 65%, UCR 73%) who were older (less than 20% under 30), educated (at least 75% had bachelor’s degrees), and relatively well off (family income exceeding $15,000 per year — adjusted to $47,600 in 2012) (Beaudry & Elster, Citation1979: 792). The demographics of who attends archaeological film festivals is valuable to understanding the potential publics being researched by archaeological outreach, but also as to who is not being drawn to such festivals. Another example is the evaluation of ‘heritage television’ audiences in the United Kingdom (Bonacchi, Citation2013; Piccini, Citation2010).

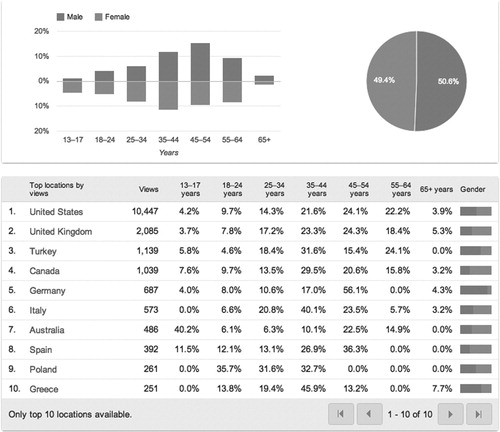

The demographics of the online audience is, to a certain extent, similar to that of the 1970s archaeology film festival audience. The tools provided by Google Analytics to assess the viewers of YouTube videos provide a fascinating comparison study to that of Beaudry and Elster’s. I uploaded my first video to YouTube on 21 January 2008. While I did not widely disseminate my video, Skeuomorphs, I did post about it on my blog — Middle Savagery — where I provided a link to the video on YouTube. Since that time, the video has been watched 1647 times, as tracked by Google Analytics in 2012. The same movie has been screened in three small film festivals, at the University of California, Berkeley, at the ‘Archaeology Indies’ at the San Francisco Presidio, and at Çatalhöyük, Turkey. Attendance at these three festivals altogether was perhaps 100 people. By putting Skeuomorphs online, I have increased the viewership of the video by nearly 17 times (see ).

Figure 3. Statistics taken from Youtube.com of views of Skeuomorphs.

As of October 2012, I have had 21,700 views of my 28 videos on YouTube. The video with the most views (4100), is What Color is Çatalhöyük?, a short film showing clips of interviews with archaeologists at Çatalhöyük, each answering the title’s question. The majority of my viewers — for all 28 videos — originate from the United States (10,400), with the second most in the United Kingdom (2080), and a slightly more surprising third place in Turkey (1140). The last is likely due to the popularity of my Çatalhöyük films. Altogether, my online videos have been seen in 126 countries. The age and gender breakdown is also sorted by country and, to a certain respect, reflects the findings of Beaudry and Elster. While I know my videos are assigned in classrooms, surprisingly few views came from the 18–24 age range (9.7%), while there was a fairly even spread in the older age ranks, (35–44) 21.6%, (45–54), 24.1%, (55–64), 22.2% — these figures refer to viewers in the USA. One of the most notable outliers is Australia, where an astonishing 40.2% of the 486 views came from the 13–17 year old age bracket. Most of the views of the videos originated from within YouTube’s webpage (82.2%), while only 11.4% came from the video viewed embedded in another website, most likely at Middle Savagery, my long-term archaeological research blog.Footnote8

Similarly, the Digital Research Video Project, an initiative to help academics make their research more accessible by the public, uploaded illustrated video podcasts to social media websites and assessed the quantitative and qualitative feedback the videos received (Pilaar Birch, Citation2013). The scripts for the videos were written by archaeologists, but the illustration, editing, and voice-over was conducted by a professional science communicator. While she does not release all of the analytics gathered from Twitter and Youtube, Pilaar Birch notes that peaks in viewership aligned with the initial release of the video, and then according to reblogging of the video over time. Increased viewership corresponded with the ‘influence’ of the person tweeting the video, with this influence measured by the number of ‘followers’ the person had.

Beyond these basic metrics, YouTube also measures retention of audience throughout the duration of the video. The short videos with varied content (fast cuts between interviews) that have been assigned for college audiences have the greatest audience retention. The series David Cohen and I filmed for the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco, introducing basic concepts of the archaeological profession to a broad audience, retained viewers for an average of 70% of the total length of the video, whereas the three-part series of Personal Histories in Archaeological Theory and Method video series that I did not create but that I uploaded by request of Margaret Conkey, are much longer, 30, 40, and 50 minutes each, and they retained audiences for 19.9%, 21.8%, and 6.3% of the length, respectively. For archaeologists concerned with communicating a complete message through video, these statistics guide filmmakers to keep movies short, direct, with varied content.

YouTube exemplifies the reach, diversity, and power of online social media for video outreach. While YouTube has been typified as a community that thrives on negativity and trolling, negative remarks and ‘dislikes’ on my videos have been minimal.Footnote9 With a robust demographic analysis system such as Google Analytics backing the viewing statistics on YouTube, archaeologists can assess the efficacy of online outreach to different stakeholders, even if these stakeholders do not leave comments on the videos. It is worth mentioning that there is a clear bias in the statistics that YouTube provides. Beyond the ability (or lack thereof) for people to view videos online in regard to their Internet speed and capabilities, the reporting of age and gender for Google statistics is suspect. In particular, the bias for age is older, as teenagers and children misrepresent themselves so they do not have content restrictions online. On YouTube the viewer must be 13 years old to have an account and 18 to view all content. Still, with the ability to host unlimited content and to closely track and interact with viewers, YouTube is an extremely powerful tool for archaeological outreach. The ‘punk’ videos of archaeological filmmakers fit in well in this venue, as Michael Strangelove gleans from Patricia Zimmerman, ‘amateur film is history from below, unexplored evidence, potentially subversive in its meanings and implications, “a necessary and vital part of visual culture”’ (Strangelove, Citation2010: 24; Zimmerman, Citation2008).

Conclusion

This discussion of archaeological filmmaking comes at a time when creating, editing, and sharing video footage has become increasingly effortless in the digital age. While access to recording devices and high-speed broadband is not universal, in societies that do have access, ‘women and disempowered groups have been among those specially benefiting from the potential democratization represented by a decentralized medium’ (Joyce & Tringham, Citation2007: 331). As a potentially democratizing medium, the moving image joins a number of other forms of recording and interpretation in archaeology. The availability of multiple kinds of digital publication formats and the move toward increased multivocality in archaeological interpretation combine as an invitation to use and experiment with digital video in archaeology (Morgan & Eve, Citation2012). As the number of archaeological films and filmmakers increase, so should our awareness of the potential for alternative representations of the past and our ability to provide more engaging stories about our profession.

In their collaboratively written book, archaeologist Joseph W. Zarzynski and documentarian Peter Pepe provide instructions regarding how to make an archaeological documentary, but ultimately implore the archaeologist to ‘find the funds to hire professional documentarians’ and posit that high quality video production raises the status of both the particular project and social science in general (Citation2012: 180). To this end, several archaeological projects have turned to crowd-funding initiatives to pay professional documentarians to help produce their films. Collaborations of this kind are common. As previously mentioned, the Digital Research Video Project employed a science communicator to produce the ultimate output for the project. Still, a directly participatory role for archaeologists in the creation of interpretations in these collaborations is required to avoid misrepresentation of the past on film. Additionally, the ability to create interpretations that are compelling and accessible, or that challenge perceptions of the past is a vital skill for archaeologists as public intellectuals and producers of culture (Hamilakis, Citation1999; Morgan & Eve, Citation2012).

Archaeological film is an exciting and increasingly porous medium; new formats, remixes, virtual worlds, reconstructions, animations, augmentations, and remediations constantly shift and change the way we can present our interpretations of the past. Cinemagraphs, animated GIFs that subtly move a single part of an otherwise still image, blend present and past in a repeating visual loop. Vine videos shot on cellphones are only seven seconds in length, cut between brief glimpses of activity; the square test pit is set up, excavation commences, the test pit is closed. Viewing interfaces allow a choose-your-own adventure style jump between salient plot points. Old photographs are blended into modern landscapes, dead relatives are photoshopped back into the living room using methods found on a short YouTube video. The future for the moving image in archaeology is bright, but currently amounts to so much digital ephemera without an increased attention to archival strategies. Without further examination of this rapidly increasing medium and consideration toward digital preservation strategies, this extraordinary archaeological record will be forgotten. There must be more work done in this field. With this article, I hope to raise awareness of archaeological film, and call for more scholarship regarding our rapidly deteriorating archaeological film archives and that we become more self-aware of our current media creation, distribution, and curation.

Note on contributor

Colleen Morgan is the EUROTAST Marie Curie Fellow at the University of York. She received her PhD in Anthropology at the University of California, Berkeley in 2012. Since that time, she has worked both as a professional and academic archaeologist on three continents, excavating sites 100 years old and 10,000 years old, and anything in-between. Her current research is based on building archaeological narratives with digital media, using photography, video, virtual reality, and mobile and locative devices. Through archaeological making she explores past lifeways and our current understanding of heritage, especially regarding issues of authority, authenticity, and identity.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank the EUROTAST research network for support for this publication. This work owes a substantial debt to Ruth Tringham for her extensive instruction in archaeological film theory and techniques as well as her colleagues at Çatalhöyük for allowing her to stick a camera into their faces. Thank you to Dan Machold and Katherine Strickland for assistance with references. The author would also like to thank the two anonymous peer reviewers for their comments and the helpful editing by the editors at Public Archaeology. This research was partially funded by a Stahl grant from the Archaeological Research Facility at the University of California, Berkeley.

Notes

1. While archaeologists have recorded their own footage in the past, putting this footage together into a narrative film with a specific vision for the production has become more common as digital video and editing tools have become more available. These technological affordances allow the filmmaking archaeologist to have control over all elements of production.

2. It also should be noted that I use the words ‘film’, ‘movie’, and ‘video’ somewhat interchangeably, perhaps revealing my position as a scholar born in the late 1970s with only passing recollections of 8 mm projectors, slides, and transparencies being used in the classroom.

3. Footage of Dorothy Garrod’s Mt Carmel excavations can be found online at: <https://vimeo.com/26801350>.

4. A more recent Time Team America has aired on the Public Broadcasting System in the United States since 2009.

5. The Internet has increased the quantity and visibility of archaeological movies that were once relegated to expensive documentary film distribution schemes or restricted use in libraries. The Archaeology Channel, a website established in 2005 by the Archaeology Legacy Institute, hosts over 175 videos curated for quality by committee. Equally, this medium hosts the ‘punk videos’ of archaeology are found on YouTube, Vine, Vimeo, and Facebook, and project websites, usually posted by the archaeologist who made the film. These videos vary in quality and content and are difficult to quantify in a meaningful way.

6. Beale and Healy use the term ‘experimental’ in this case to indicate the films made about experimental archaeology, that is, people in the present replicating past practices.

7. Observational video, an ethnographic film genre that attempts to edit films in a way that is closer to classic fiction films (Barbash & Taylor, Citation1997) are not quantified in this article, as it is a rare practice in archaeological filmmaking.

8. Blog available at <http://middlesavagery.wordpress.com>.

9. In Watching YouTube, Michael Strangelove casts the negativity of YouTube as a larger problem with Internet communities and anonymity (2010: 118–20).

Bibliography

- Allen, P. & Lazio, C. 1983. Archaeology on Film: A Comprehensive Guide to Audio-Visual Materials. Boston: Archaeological Institute of America.

- Anderson, S. 2006. The Past in Ruins: Postmodern Politics and the Fake History Film. In: A. Juhasz and J. Lerner, eds. F is for Phony: Fake Documentary in Theory and Practice. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, pp. 76–90.

- Ascherson, N. 2004. Archaeology and the British Media. In: N. Merriman, ed. Public Archaeology. London: Routledge, pp. 145–58.

- Ashley, M. 2004. An Archaeology of Vision: Seeing Past and Present at Çatalhöyük, Turkey. Unpublished PhD thesis, University of California, Berkeley.

- Bailey, G., Newland, C., Nilsson, A., Schofield, J., Davis, S., & Myers, A. 2009. Transit, Transition: Excavating J641 VUJ. Cambridge Archaeological Journal, 19(1): 1–28.

- Barbash, I. & Taylor, L. 1997. Cross-Cultural Filmmaking: A Handbook for Making Documentary and Ethnographic Films and Videos. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Beale, T. W. & Healy, P. F. 1975. Archaeological Films: The Past as Present. American Anthropologist, 77(4): 889–97.

- Beaudry, M. & Elster, E. 1979. The Archaeology Film Festival: Making New Friends for Archaeology in the Screening Hall. American Antiquity, 44(4): 791–94.

- Bolter, J. D. & Grusin, R. 2000. Remediation: Understanding New Media. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Bonacchi, C. 2013. Audiences and Experiential Values of Archaeological Television: The Case Study of Time Team. Public Archaeology, 12(2): 117–31.

- Boon, T. 2008. Films of Fact: A History of Science in Documentary Films and Television. London: Wallflower Press.

- Boyd, D. 2011. Facebook and ‘radical transparency’ (a Rant) on Apophenia [accessed 1 October 2012]. Available at: <http://www.zephoria.org/thoughts/archives/2010/05/14/facebook-and-radical-transparency-a-rant.html>.

- Brill, D. 2000. Video-Recording as Part of the Critical Archaeological Process. In: I. Hodder, ed. Towards Reflexive Methods in Archaeology: The Example at Çatalhöyük. Cambridge: McDonald Institute of Archaeological Research, pp. 229–34.

- Bruzzi, S. 2000. New Documentary: A Critical Introduction. London: Routledge.

- Casebier, A. 1991. Film and Phenomenology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Chadwick, A. 2003. Post-Processualism, Professionalisation and Archaeological Methodologies. Towards Reflective and Radical Practice. Archaeological Dialogues, 10(1): 97–117.

- Clack, T. & Brittain, M. 2007. Archaeology and the Media. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press.

- Cole, J. R. 1972. Motion Pictures as an Archaeological Data Source. Program in Ethnographic Film Newsletter, 4(1): 12–13.

- Daniel, G. 1954. Archaeology and Television. Antiquity, 28: 201–05.

- Day, D. H. 1997. A Treasure Hard to Attain: Images of Archaeology in Popular Film, with a Filmography. London: Scarecrow Press.

- Downs, M., Allen, P. S., Meister, M. J., & Lazio, C. 1993. Archaeology on Film. Dubuque, IA: Archaeological Institute of America Kendall/Hunt Publishing Company.

- Earl, G. P. 2004. Video Killed Engaging VR? Computer Visualizations on the TV Screen. In: S. Smiles and S. Moser, eds. Envisioning the Past: Archaeology and the Image. Malden, US and Oxford, UK: Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 204–22.

- Elmer, G. 2003. A Diagram of Panoptic Surveillance. New Media Society, 5(2): 231–47.

- Finn, C. 2001. Mixed Messages: Archaeology and the Media. Public Archaeology, 1(4): 261–68.

- Floyd, D. P. 1970. Index of Movies on Archaeology. Stones and Bones Newsletter, (March): 9.

- Foucault, M. 1975. Discipline and Punish: the Birth of the Prison. New York: Random House.

- Garner, R. 1954. The Ancient World on Film. Archaeology, 7(4): 202–05.

- Girouard, L., Boivin, R., & Laberge, M. 1973. Communication Audio-Visuelle en Archéologie. Recherches Amérindiennes au Québec, 3(5): 7–58.

- Goodwin, C. 1994. Professional Vision. American Anthropologist, 96(3): 606–33.

- Hall, M. A. 2004. Romancing the Stones: Archaeology in Popular Cinema. European Journal of Archaeology, 7(2): 159–6.

- Hamilakis, Y. 1999. La trahison des archéologues? Archaeological Practice as Intellectual Activity in Postmodernity. Journal of Mediterranean Archaeology, 12(1): 60–79.

- Hanson, W. S. & Rahtz, P. A. 1988. Video Recording on Excavations. Antiquity, 62: 106–11.

- Hawkes, J. 1946. The Beginning of History: A Film. Antiquity, 20: 78–82.

- Heizer, R. F. & Kroeber, T. 1981. Ishi, the Last Yahi: A Documentary History. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Hodder, I. 1997. Always Momentary, Fluid and Flexible: Towards a Reflexive Excavation Methodology. Antiquity, 71: 691–700.

- Holtorf, C. 2007. Archaeology is a Brand! The Meaning of Archaeology in Contemporary Popular Culture. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press.

- Joyce, R. & Tringham, R. E. 2007. Feminist Adventures in Hypertext. Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory, 14: 328–58.

- Kraemer, C. J. Jr. 1958. The Archaeological Film. Archaeology, 11: 262–66.

- Kulik, K. 2006. Archaeology and British Television. Public Archaeology, 5(2): 75–90.

- Laude, J. 1970. Cinéma et Archéologie. Films d’Intérêt Archéologique, Ethnographique ou Historique. Paris: UNESCO, pp. 11–35.

- Lyon, E. A. 1996. A New Deal for Southeastern Archaeology. Tuscaloosa, AL: University of Alabama Press.

- MacDougall, D. 1997. The Visual in Anthropology. In: M. Banks and H. Morphy, eds. Rethinking Visual Anthropology. New Haven, CT and London: Yale University Press.

- Manovich, L. 2001. Modern Surveillance Machines: Perspective, Radar, 3-d Computer Graphics and Computer Vision. Rhetorics of Surveillance: From Bentham to Big Brother. Karlsruhe: ZKM/Zentrum für Kunst und Medientechnologie and Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Miller, D. 1972. Archaeology and Film: A Conflict of Reality? Programme in Ethnographic Film Newsletter, 4(1): 7–8.

- Morgan, C. & Eve, S. 2012. DIY and Digital Archaeology: What Are You Doing to Participate? World Archaeology, 44(4): 521–37.

- Moulin, M. D. 1972. Films as an Aid to Archaeological Teaching. New York: Archaeological Institute of America.

- Nichols, B. 1991. Representing Reality: Issues and Concepts in Documentary. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

- Nixon, L. 2010. Seeing Voices and Changing Relationships: Film, Archaeological Reporting, and the Landscape of People in Sphakia. In: A. Stroulia and S. B. Sutton, eds. Archaeology in Situ: Sites, Archaeology, and Communities in Greece. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

- Pepe, P. & Zarzynski, J. W. 2012. Documentary Filmmaking for Archaeologists. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press.

- Perry, S. 2012. Who Exactly is a Real Archaeologist? [accessed 10 October 2012]. Available at: <http://saraperry.wordpress.com/2012/09/20/who-exactly-is-a-real-archaeologist/>.

- Piccini, A. 1996. Filming Through the Mists of Time: Celtic Constructions and the Documentary. Current Anthropology, 37(1): 87–111.

- Piccini, A. 2007. Faking It: Why the Truth is so Important for TV Archaeology. In: T. Clack and M. Brittain, eds. Archaeology and the Media. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press, pp. 221–36.

- Piccini, A. 2009. Guttersnipe: A Micro Road Movie. In: C. Holtorf and A. Piccini, eds. Contemporary Archaeologies: Excavating Now. New York: Peter Lang, pp. 183–200.

- Piccini, A. 2010. The Stuff of Dreams: Archaeology, Audience and Becoming Material. In: S. Koerner and I. Russell, eds. Unquiet Pasts: Risk Society, Lived Cultural Heritage, Re-designing Reflexivity. Farnham: Ashgate, pp. 305–26.

- Piccini, A. (in press). Theory in the Public Eye: Archaeology and the Moving Image. In: A. Gardner, M. Lake, and U. Sommer, eds. The Oxford Handbook of Archaeological Theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Pilaar Birch, S. 2013. Using Social Media for Research Dissemination: The Digital Research Video Project. Internet Archaeology, 35. Council for British Archaeology.

- Ramsay, A. E. 2007. Excavating Television: Examining the Use of Mass Media to Foster Public Engagement with Archaeology at the Presidio of San Francisco. Unpublished PhD thesis, University of California, Berkeley.

- Rodowick, D. N. 2007. The Virtual Life of Film. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Ruby, J. 1969. 4 — Butte — 1: A Lesson in Archaeology. Produced by Peter Schnitzler. American Anthropologist, 71: 380.

- Ryzewski, K. 2009. Seven Interventions with the Flatlands: Archaeology and its Modes of Engagement. Contributions from the WAC-6 Session, ‘Experience, Modes of Engagement, Archaeology’. Archaeologies, 5(3): 361–88.

- Schablitsky, J. M. 2007. Box Office Archaeology. Refining Hollywood’s Portrayals of the Past. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press.

- Schablitsky, J. M. & Hetherington, N. 2012. Archaeology on the Screen. In: M. Rockman and J. Flatman, eds. Archaeology in Society: Its Relevance in the Modern World. New York: Springer, pp. 139–52.

- Shanks, M. 1997. Photography and Archaeology. In: B. Molyneaux, ed. The Cultural Life of Images: Visual Representation in Archaeology. New York: Routledge, pp. 73–107.

- Sherman, S. R. 1998. Documenting Ourselves: Film, Video, and Culture. Knoxville, KY: University Press of Kentucky.

- Sobchack, V. 1991. The Address of the Eye: A Phenomenology of Film Experience. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Stern, T. 2007. ‘Worldwonders’ and ‘Wonderworlds’: A Festival of Archaeological Film. In: T. Clack & M. Brittain, eds. Archaeology and the Media. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press, pp. 201–20.

- Stone, J. 1991. Computer Applications in Archaeology: Graphics, Database, and Image Processing in a Multimedia Field-to-Publication Data Management System. Social Science Computer Review, 9(1): 39–61.

- Strangelove, M. 2010. Watching YouTube: Extraordinary Videos by Ordinary People. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Tringham, R. 2009. Making the Most of the Medium of Film to Create Alternative Narratives about the Past and its Investigation. Paper presented at the conference Archéologie et Médias Quelles Représentations, Quels Enjeux? Brussels, Belgium.

- Tringham, R., Ashley, M., & Mills, S. 2007. Senses of Places: Remediations from Text to Digital Performance [accessed 3 March 2012]. Available at: <http://chimeraspider.wordpress.com/2007/09/19/remediated-placesfinal-draft>.

- Tringham, R., Ashley, M., & Quinlan, J. 2012. Creating and Archiving the Media Database and Documentation of the Excavation. In: R. Tringham and M. Stevanović, eds. House Lives: Building, Inhabiting, Excavating a House at Çatalhöyük, Turkey: Reports from the BACH Area, Çatalhöyük, 1997–2003. Los Angeles, CA: Cotsen Institute of Archaeology, pp. 31–48.

- Van Dyke, R. M. 2006. Seeing the Past: Visual Media in Archaeology. American Anthropologist, 108(2): 370–75.

- Vogt, E. Z. 1955. Anthropology in the Public Consciousness. Yearbook of Anthropology, 357–74.

- Wahlberg, M. 2008. Documentary Time: Film and Phenomenology. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

- Wickstead, H. 2009. The Uber Archaeologist: Art, GIS and the Male Gaze Revisited. Journal of Social Archaeology, 12: 245–63.

- Witmore, C. 2004a. On Multiple Fields. Between the Material World and Media: Two Cases from the Peloponnesus, Greece. Archaeological Dialogues, 11(2): 133–64.

- Witmore, C. 2004b. Four Archaeological Engagements with Place: Mediating Bodily Experience through Peripatetic Video. Visual Anthropology Review, 20(2): 57–72.

- Witmore, C. 2005. Multiple Field Approaches in the Mediterranean: Revisiting the Argolid Exploration Project. Stanford, CA: Metamedia.

- Zimmerman, P. R. 2008. Morphing History into Histories: From Amateur Film to the Archive of the Future. In: K. L. Ishizuka and P. R. Zimmermann, eds. Mining the Home Movie: Excavations in Histories and Memories. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.