Abstract

In providing free access to educational resources from some of the most prestigious universities in the world, Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) have been hailed as both a revolution and threat for the ‘traditionally elite’ higher education system. Stepping away from the label of ‘traditionally elite’, this article argues that universities actually have relatively open origins and that the democratisation of higher education, as espoused by the big MOOC providers, is not entirely new. Instead, this retrospective analysis of the development of universities indicates a cyclical model of change, one in which waves of inclusivity alternate with bouts of exclusivity. In highlighting this issue, and parallel ideas about university as a ‘place’, this historical overview provides a useful backdrop to contemporary debates about MOOCs. It shows how MOOCs, as they currently appear, are neither revolutionising nor destroying higher education, they are simply part of its cyclical evolution.

Introduction

This article presents a historical overview of the development of universities, illustrating that — despite what their champions, sceptics, and doomsayers suggest — Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs), as they currently appear, are neither revolutionising nor destroying higher education, they are simply the latest point of tension in its cyclical evolution. While the idea of a ‘MOOC’ has existed since 2008, it was not until 2012 that the term entered popular discourse. This was the year in which academics from some of the most prestigious universities in the USA — and consequently the world — started offering their model of MOOCs under the banners of Udacity, Coursera, and edX; the so-called ‘Year of the MOOC’ (Pappano, Citation2012).

MOOCs, as their protracted name suggests, are a form of higher education which — according to the three above-mentioned providers — can occur anywhere, anytime, via the internet (Coursera, Citation2013; edX, Citation2013; Udacity, Citation2013). However, this alone is not enough to distinguish MOOCs from two other forms of anywhere, anytime learning: distance education and online education (also known as online learning), both of which have a much longer history in higher education than MOOCs and now use the internet as their prime means of delivery (Harasim, Citation2000; Sumner, Citation2000: 277–79). One distinction between the latter two concerns how people engage in the learning process. Generally, online education is seen as a group learning exercise, whereas distance education is regarded as much more individualistic (Bejerano, Citation2008: 409–10; Harasim, Citation2000: 49–50). Another distinction is in their ethos. Distance education providers largely present an emancipatory agenda, one which vows to remove barriers imposed by distance, social and educational background, and competing work and relational priorities (Guri-Rosenblit, Citation2005: 472). Online education, while still providing a means to overcome these obstacles, promotes convenience and global connectedness, regardless of the actual distance that exists between learner and provider (Aslanian & Clinefelter, Citation2012; Capra, Citation2011: 288). It is this combination of emphases that puts MOOCs in the online education space, shrouded in rhetoric of both the emancipation of, and convenience for, a new global network of consumers. What tends to set MOOCs apart, however, is that, unlike conventional online higher education programmes, they have:

| • | no formal requirements for entry | ||||

| • | no limit on the number of people that can take part at any given time | ||||

| • | no requirement for study in a programme beyond individual courses | ||||

| • | no resulting credentials, and | ||||

| • | for the vast majority, no fees either — except for certificates of completion in some cases (Gaebel, Citation2013). | ||||

These characteristics, MOOC providers claim, put them within the gambit of the Open Educational Resources (OER) movement, which emerged in 2002 from the idea that technology should be used to ensure higher education resources are not just available anywhere, anytime, but also are freely available to anyone (Matkin, Citation2012; Walsh, Citation2011: 19–20).

Divergent views on the promises and pitfalls of each of the five above-mentioned characteristics (accessibility, scale, modularity, credentialisation, and cost), and whether or not MOOCs truly adhere to the ‘open’ philosophy of the OER movement, indicate that MOOC commentators can be divided into three distinct groups: champions, sceptics, and doomsayers. Champions of MOOCs argue that, by offering free online access to educational resources from some of the world’s most prestigious universities, MOOCs are indeed opening up higher education and making it more inclusive than ever before (Jelley & Scanlon, Citation2013; Miller, Citation2012; Mulholland, Citation2013; Young, Citation2013). Sceptics argue that MOOCs present the opposite scenario — a shift towards greater exclusivity and inequality — with one form of short, credit-less education for the masses and another for the elite few who can afford the ‘traditional’ on-campus experience (Andrews, Citation2013; Craig, Citation2012; Jaschik, Citation2013). Doomsayers go one step further, arguing that, by giving away content from prestigious universities for free, MOOCs represent a break from the ‘knowledge gatekeeper’ role of all universities, one that diminishes the relevance of campus-based higher education and may be its ultimate demise (Barber et al., Citation2013; Harden, Citation2013; Shirky, Citation2012).

Purpose and scope of this article

To establish whether or not MOOCs represent a shift towards greater ‘inclusivity’ or ‘exclusivity’ in higher education, or a sign of their demise, first one must consider the historical development of universities — the primary higher education providers. That is the purpose of this article: not to provide an assessment of the future implications of MOOCs, but an analysis of the historical antecedents of MOOCs, including the general developments and accessibility of universities over time. The key research question, therefore, is: based on this review of universities, are MOOCs in line with the historical trajectory of higher education, as conceived as a system, or do they represent a break from this system?

As the history of universities and ideas about higher education constitute an expansive topic, it is beyond the scope of this article to address the peculiarities of all nations in detail. In favouring a more general view, this article utilises the approaches of Tight (Citation2012) and Clark (Citation1983) in its analysis of higher education as a ‘system’. Both acknowledge the term’s specificity, often taken to mean analysis of higher education providers within a particular country, on an aggregate and national level. At the same time, each proposes the necessity of a broader definition of the system, one that encompasses the conceptualisation of higher education as a whole and includes all people, organisations, and countries encompassed under such a banner (Clark, Citation1983: 4–5; Tight, Citation2012: 219–20). In this vein, the system of higher education as I am approaching it includes the various iterations of universities and developments in higher education observed throughout history. Such a broad definition, Clark (Citation1983: 50) argues, is necessary to capture the ways in which systems can ‘expand and contract, zig and zag, across time and space’. The ‘zigs and zags’ that I wish to emphasise are the key points of tension in the general development of higher education over time, i.e. the cyclical waves wherein inclusive and exclusive access have alternated according to changing social circumstances.

Although this article primarily focuses on this broadly conceived system level, there are some instances where specific Western countries are referenced. The reasoning behind this emphasis is twofold. First, MOOCs originated in Western countries. They were given life by a group of academics in Canada (at the University of Manitoba) and then later co-opted and popularised by big-name universities in the USA (Stanford, Harvard, and MIT) (Bady, Citation2013). Second, these institutions from which MOOCs have sprung are themselves based — as are universities around the world — to some degree or another, on their medieval Western European predecessors (Altbach, Citation1998: 348; Barnett, Citation1990: 18; Cobban, Citation1975: 21–22; Fehl, Citation1962: 233; Husén, Citation1991: 174; Verger, Citation1992: 35). In other words, within the global system of higher education, universities share ‘common historical roots’, partly due to the legacy of European colonisation in Asia, Africa, and South America, but also because of the adoption and adaptation of Western university models in non-colonised nations, like Japan, Thailand, and China (Altbach, Citation1996: 21–23).

Rather than seeing universities as being ‘traditionally’ elitist (Husén, Citation1991: 173; Leach, 2013: 268; Simmons, 2002), or MOOCs as the democratising innovation that will abolish the university (Brooks, 2012; Leckhart, 2012), this article argues that universities and ideas about higher education, at least from a Western perspective, actually originated with inclusivity in mind, and that the democratisation of higher education, as espoused by the big MOOC providers, is not entirely new. Instead, the historical development of universities indicates a cyclical model of change, where waves of inclusivity alternate with bouts of exclusivity. Furthermore, the idea that university education is ‘traditionally’ campus-based, and that the anywhere, anytime learning promise of MOOCs therefore presents a serious threat to the foundations of higher education, is shown to be a flawed assessment of history. Essentially, universities did not have elite origins, nor did they originate as ‘places’ (Byrd, Citation2001: 2). Instead, ideas about the importance of place and campus life appear to be linked to changing social conditions and technologies, as well as varying attitudes and policies about higher education over time. The emergence of MOOCs simply represents the latest incarnation of these ideas, albeit in an increasingly diversified context as far as university goals, structures, and operations are concerned.

Recognising change in higher education

According to Barnett (Citation1990: 23), what generally distinguishes higher education from other forms of learning is the quest for knowledge and truth by way of critical thinking, reason, and debate. In adopting these general values, universities have become the primary higher education providers with the power to legitimise knowledge production, acquisition, and dissemination, and the authority to award degrees (Frijhoff, Citation1992: 1252). Now that non-university providers increasingly are entering the higher education arena, one could argue that the power of universities in this area has diminished, or at least that the landscape of higher education has been fundamentally altered (LeBlanc, Citation2013). The paradox is that higher education providers, particularly universities, long have been criticised for their inability, or at least unwillingness, to change (Garrison & Kanuka, Citation2004: 102). The fact that many regard universities as being virtually unchanged since their inception is testament to the claim that universities see change as a threat, and that resistance to change should stand as a mark of honour and legacy (Garrison & Kanuka, Citation2004: 104). However, as Altbach (Citation1996: 22) proposes, research into the origins and development of universities and the idea of higher education begets another story: not one of fixed foundations, but of continuous evolution.

According to Pritchard (Citation1998: 71), such ‘dynamic life cycles’ tend to be overlooked since change in universities often takes place over long periods of time. Because of this apparent blindness to transformation over shorter periods, it seems that much of the discourse surrounding the emergence of MOOCs has been bookended with the ‘oldest’ and ‘newest’ elements of the story: that universities emerged in medieval Europe and are only now, through the proliferation of MOOCs, beginning to provide inclusive access to higher education (LeBlanc, Citation2013: 44; Marklein, Citation2012; Pappano, Citation2012; Weissmann, Citation2012). As Siemens (Citation2012) — one of the early Canadian pioneers of MOOCs (albeit a different model to that which has since emerged from the USA) — points out, such a narrow view of the historical roots of MOOCs ignores the role that the OER movement, as well as online education and internet communications technologies generally, had to play in their development. I go back even further than this to say that such a short-sighted depiction of the prehistory of MOOCs actually distorts the evolution of universities over centuries, if not millennia, when ideas about higher education first came to be. While Siemens & Matheos (Citation2010) previously has acknowledged the ancient roots of higher education, I emphasise the cyclical evolution that has occurred ever since. An assessment of this cyclical evolution is necessary to interrogate the historical legitimacy of claims about the impact that MOOCs are having on the nature of higher education, particularly on universities. Only by conducting a thorough review of the past can we understand how we got to where we are today. Such retrospection inevitably means accounting for social change.

In the broadest sense, social change can be thought of as structural, that is, irreversible, or cyclical (Hooker, Citation1997: 21). While significant societal changes throughout history mean that each iteration of higher education is unique, it is possible to identify reoccurring ‘rhythms’ or echoes throughout the last 2,400 years and, thus, a cyclical model of change (Papenhausen, Citation2009: 5). The rhythms here, as previously mentioned, are alternations between periods of inclusivity and exclusivity within the higher education system over time. In this sense, openness — one of the key elements associated with the rise of MOOCs — is not a new concept, nor is the contrasting notion that many universities, to some degree, have been closed off from the majority of society (Titze, Citation1987: 349).

Inclusive origins: ancient ideas about higher education

The history of higher education, and of universities, is inextricably linked to the history of thought. It is no surprise, therefore, that the origin of higher education is often traced back to Socrates, regarded as both ‘the father of Western philosophy’ (Tweed & Lehman, Citation2002, Citation2003) and ‘the ideal teacher’ (Sichel, Citation1996: 616). Socrates (469–399 bc) lived at a time plagued by external threats and internal corruption, the latter ultimately leading to his execution (Nails, Citation2006, Citation2009). Oddly, it was also a time of increasing interest in advanced, albeit relatively unsystematised, forms of education, as well as intellectual enquiry that challenged traditional beliefs (Spies, Citation2000: 20; Woodruff, Citation2011). It was here that the well-known philosophy teachers of the day (the ‘sophists’) began giving lectures to young aristocratic men, paid in advance for their instruction (Clarke, Citation1971: 1; Nails, Citation2009; Power, Citation1964: 162).

While many now regard Socrates’ own dialogues as a form of teaching, Socrates himself apparently shied away from such a moniker (Davis & Steinglass, Citation1997: 262). For him, teachers of his day, like the sophists, were not intent on sharing or inciting new knowledge so much as depositing their ‘expert’ information stocks into the passive minds of a paying audience (Pattyn, Citation2006: 194). Socrates, in contrast, employed a more dynamic and less financially-driven approach in his philosophical ‘teachings’ (Marrou, Citation1956: 58; Russell, Citation1961: 101). Rather than pandering to the paying masses, Socrates would simply meet up with inquisitive youths in public places and engage them in dialogue; probing them with repeated questions on topics such as goodness, truth, and justice with the intention of provoking intellectual curiosity and critique (Savin-Baden, Citation2000: 3; Wang, Citation2010; Zeller, Citation1876). This interactive tactic was heralded the ‘Socratic method’ of teaching, and has been widely adopted in education practices ever since (Benson, Citation2011; Wang, Citation2010). Unfortunately, the Athenian authorities at the time did not think much of Socrates’ efforts, sentencing him to death by poison on a charge of civil disobedience and corruption of Athenian youths through ungodly and hedonistic preachings (Nails, Citation2009; Russell, Citation1961: 103; Schofield, Citation2008).

Plato (429–347 bc) was one youth said to have been in Socrates’ ‘intimate circle’, and is the person to whom we owe much of our historical understanding of the earlier philosopher (Kraut, Citation2013; Schofield, Citation2008). Whereas Socrates saw internal reflection or ‘self-examination’ as the key to higher order knowledge, Plato saw such knowledge as a quest for an objective truth beyond the subjective mind of the individual, and therefore something that could be shared and taught (Martin, Citation2000: 178–79; Rowe, Citation2011). With this in mind, Plato founded a learning community which, unlike Socrates’ dialogues, had a specific name (‘the Academy’), a regular meeting place (Plato’s garden), and explicit membership — although it is said that, because there was little distinction between the garden and neighbouring public spaces, anyone could listen in on discussions (Dillon, Citation2003: 3; Martin, Citation2000: 179). Whatever subject was under scrutiny, the overarching emphasis of the Academy seemed to be on critical enquiry and debate beyond the realm of ‘ordinary knowledge’ (Barnett, Citation1990: 17–18), to undertake rigorous investigation ‘to seek to find what one does not know’ (Plato, 2002).

As a semi-formal community of scholars, Plato’s Academy is sometimes credited with being the ‘world’s first university’ (Pedersen, Citation2000: 12). Others, however, regard the Academy as more of an informal congregation of intellectuals, utterly distinct from the formal teaching at universities (Fehl, Citation1962: 32; Martin, Citation2000: 179; Power, Citation1964: 155–56). Still, what set the Academy apart from previous educational endeavours, making it an important part of the history of higher education (and prehistory of MOOCs), was that, like Socrates, it did not charge fees for tuition (Coulson, Citation1996: 7). Instead, participation was relatively inclusive and motivated by intellectual curiosity and the quest for ‘higher order’ knowledge beyond the everyday (Monoson, Citation2000: 138–39). As the years passed, and the Roman Empire expanded — thereby bringing it into closer contact with the older culture of the Greeks — these intellectual practices became embedded in Roman life (Corbeill, Citation2001). Subsequently, while the origins of Western conceptions of higher education may have been Greek, it was the mobility and colonisation of Europe by the Romans that truly dispersed Western intellectualism throughout Europe and, subsequently, the world (Clarke, Citation1971: 14; Durkheim, 1977: 19–20).

The cathedral schools: ecclesiastical restrictions on early teachings

With the extension of the Roman Empire came the expansion of the Roman Catholic Church. This provided a disjuncture with the pagan beliefs of Greek scholars and, subsequently, a view that perhaps there should be separate space for Christian teachings which need not pay homage to these traditions (Durkheim, 1977: 19–20; Highet, Citation1976: 8). For a long time, such alternative instruction was limited to cathedrals and monasteries, which became the primary education providers in Western Europe following the demise of the Roman Empire in this region from the fifth century onwards (Clarke, Citation1971: 119–40; Cobban, Citation1975: 3; Siemens & Matheos, Citation2010). Eventually, demand for education outstripped the capacity of the cathedral schools, and gradually more schools began cropping up separate to the church. Not surprisingly, education began to take on increasingly secular interests (Cobban, Citation1975: 9; Durkheim, 1977: 25, 78). This divergence in school settings was the source of much conflict between church and state, as education became increasingly seen as a tool to help serve the needs of society, not just the needs of the clergy (Cobban, Citation1975: 8; Durkheim, 1977: 83). This greater emphasis on societal need was largely to do with the fact that Western Europe was becoming more urbanised from the ninth century onwards (van Werveke, Citation1965: 3). It was here that medieval towns began to emerge as a result of fortifications erected to protect Western Europeans from threats of invasion from the east (van Werveke, Citation1965: 8). By the eleventh century, these towns had become areas of burgeoning activity; the centres of social, economic, and intellectual life (Pedersen, Citation2000: 103; Perry et al., Citation2007: xxvi).

The first universities: accessible and mobile communities

From these medieval European towns came the pillar of higher education that we now know as the university. Just as one can trace contemporary universities back to these common medieval roots, so too can one garner a general image of these medieval European predecessors (Power, Citation1991). While definite founding dates are not known, since early universities tended to evolve into being without the specific intention of doing so, it is generally agreed that the world’s first two universities were the University of Bologna, which emerged some time around the end of the eleventh century, and the University of Paris, established in the early twelfth century (Pedersen, Citation2000: 155; Siemens & Matheos, Citation2010). Oxford, the first British university, emerged at the end of the twelfth century (Cobban, Citation1992: 1247).

The difficulty in isolating the precise moment when schools operating separately from the cathedral became ‘universities’ is because there are few records from this time that discuss exactly what went on within the confines of these communities (Durkheim, 1977: 88; Pedersen, Citation2000: 1; Rüegg, Citation1992: 3). Emphasis here on the word ‘community’ is important, as this is precisely what the earliest universities were. The original meaning of the Latin term universitas was ‘a corporation’; a guild-like society of students and teachers, not a place (Graves, Citation1910: 86–87; Lewis & Short, Citation1933: 1933). Without a specified location, the earliest universities were effectively ‘rootless’ communities that could come and go as they pleased (Durkheim, 1977: 89).

One of the main propositions put forward by champions of MOOCs is that they represent a new way of thinking regarding the provision of higher education — one of greater accessibility to high-quality knowledge resources for more people from more places than ever before (Lewin, Citation2012; Mulholland, Citation2013). However, various authors have argued that this theme of democratisation of higher education is nothing new (Delanty, Citation2002: 6; McCluskey & Winter, Citation2012: 33–34). As already discussed, the Ancient Greek ideas about higher education from Socrates and Plato were quite inclusive in terms of participation. Early universities appear to have been similarly accessible, the difference being that learning had become systematised and credentialised with the regulation of specified courses and the awarding of degrees (Clarke, Citation1971: 141; Frijhoff, Citation1992: 1252; Power, Citation1991: 153).

Aside from there being no entry fees, the earliest universities had no formalised academic, age, or calendar requirements for entry, nor was there a requirement for the completion of a degree (Barnett, Citation1990: 19; Pedersen, Citation2000: 213; Schwinges, Citation1992: 171). Having said that, students still had to speak Latin, as this was the common language of instruction; for the most part they had to be male; and they had to have the financial means to be able to support themselves with food and accommodation, particularly during their preparatory studies (Cobban, Citation1992: 1250; Pedersen, Citation2000: 14–15; Scott, Citation2006: 7). In some cases, they also had to prove the legitimacy of their birth if pursuing anything higher than a bachelor’s degree, but, according to Schwinges (Citation1992: 171), this was likely to have been a rare occurrence.

It is important to note that there was also no requirement for citizenship and that students from any nation could enrol at a university if they met the above-mentioned criteria (Perkin, Citation2006: 160; Rait, Citation1969: 8; Schwinges, Citation1992: 171). Because of this, and the international mobility of the overall populace during this period of urbanisation, trading, and highly porous borders, medieval European universities were inherently international and, consequently, their student body consisted of foreigners (Altbach, Citation1998: 348; Verger, Citation1992: 41).

All of this suggests that, for young men at least, it was relatively easy to access a university education in medieval Europe compared to the so-called ‘traditionally elitist’ agenda associated with many universities today (Durkheim, 1977: 67; Pedersen, Citation2000: 96). In the words of Power (Citation1991: 149), universities during this medieval scholarly period were essentially keen promoters of ‘an open educational society’ — far more so than the cathedral schools which had preceded them (Bender, Citation1988: 4).

Universities as places: sparking a trend towards exclusion

Despite claims that universities encompass both ‘the pursuit of learning’ and a ‘place of learning’, as Oakeshott (Citation2004: 24) argues, the notion of place, as previously alluded to, was not a defining characteristic of the earliest universities. Purpose-built lecture halls, libraries, and accommodation did not appear until the fifteenth century (Durkheim, 1977: 89; Gieysztor, Citation1992: 139). Prior to this, lecturers would hire out church buildings and rooms in other establishments to teach and therefore could entertain any number of intellectual curiosities in any number of co-opted spaces (Cobban, Citation1992: 1247; Gieysztor, Citation1992: 136–37). Once dedicated structures for housing academics and students had been erected, universities were no longer rootless; they had become permanent civic fixtures (Bender, Citation1988). As a result, they were much more likely to stay in one location and build up a strong resource base instead of migrating, with limited resources, to another town (Gieysztor, Citation1992: 139; Rait, Citation1969: 18).

While it is not entirely clear when universities started restricting entry by charging for tuition, it does seem as though there was a gradual trend towards exclusion after these purpose-built buildings first started being erected and, subsequently, university lifestyle began to change (Rait, Citation1969: 18). Whereas the earliest incarnations of universities promoted a very accessible and modest life among both teachers and students, from around the sixteenth century, universities took on a much more aristocratic flavour (di Simone, Citation1996: 312; Frijhoff, Citation1996: 368). True, the overall sentiment of the sixteenth century was one of great enthusiasm for intellectual pursuits, as indicated by the proliferation of universities across Europe (Spies, Citation2000: 23). However, significant changes were afoot, not just regarding the governance of Europe, but also the make-up of its universities. Religious and territorial divisions across the continent during the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries gave rise to the creation of new nation states, separated according to different monarchic, religious, and ethnic factions (Gorski, Citation1999: 148). With these new states arose new bureaucracies, established to manage state affairs (Perry et al., Citation2007: 360–63). The widespread push for a new, highly skilled, and increasingly prestigious bureaucracy meant that, by the sixteenth century, wealthy aristocrats were in the market for a university education more so than they had ever been before (Dewald, Citation1996: 143–44; Frijhoff, Citation1992: 1257; Scott, Citation2006: 11). State funding in universities also increased, staking a claim for national investment into this burgeoning public workforce (di Simone, Citation1996: 298–99; Frijhoff, Citation1996: 362; Müller, Citation1996: 326). The development of the early modern nation state, and its associated bureaucracy, thus triggered an increasing aristocratisation and nationalisation of what was a previously diverse, international, and relatively accessible educational environment (Perkin, Citation2006; Scott, Citation2006: 10–11).

The rise of meritocracy: a new criterion for inclusion/exclusion

By the eighteenth century, one could be forgiven for thinking that universities had been designed to cater primarily for the upper echelons of society, with those of more limited financial means having been all but removed from the system, unable to compete for scholarships and jobs with those who had deeper pockets and elite social connections (Perkin, Citation1984: 29–30). Not everything about universities at this time was considered top class, however, as many universities came under scrutiny by national officials for their inability to meet the training standards that state authorities required (Frijhoff, Citation1992: 1257). Because of the public investments made in universities for this exact purpose, dissatisfaction from authorities inevitably meant greater state interference in university operations, particularly with regard to entry requirements, areas of study, and practical training outcomes (Frijhoff, Citation1996: 386; Müller, Citation1996: 326). For a start, entry to university ceased to be dependent on high social standing, as had become increasingly the trend over the previous 200 years. Instead, entry became based on academic merit, ensuring that only the highest performing and most skilled graduates were working for the state (Frijhoff, Citation1992: 1257). While ostensibly more democratic than in years past, even entry based on merit was still more likely to be restricted, by and large, to those from higher social strata, not necessarily because of the rising cost of living generally, but because of increases in the cost of going to university and maintaining the extravagant lifestyle of ‘gentleman undergraduates’ which had developed over time (di Simone, Citation1996: 312; Perkin, Citation1984: 29–30).

Managing tension: alternation between periods of inclusion and exclusion

Restrictions on university entry in the eighteenth century were partly in response to growing concerns about an excess of intellectuals required by society; in other words, the potential for civil unrest from some of the best, albeit unemployed, minds in Europe — ‘the alienated intellectuals’ (di Simone, Citation1996: 301–02; Frijhoff, Citation1992: 1258, 1996: 386). This ‘excess of supply’ argument appears to be cyclical, coinciding with fluctuations between periods of growth and decline in university admissions (Frijhoff, Citation1992: 1258; Ringer, Citation2004: 235). Rather than being something which can be measured solely in terms of market value, since arguments over excess enrolments appear to have predated industrial capitalism, it has been suggested that recurring attempts to cap university entry have been predominately aimed at maintaining social equilibrium, such as limiting competition for professional careers from the lower classes (Frijhoff, Citation1992: 1258; Schofer & Meyer, Citation2005: 901; Titze, Citation1987: 361). Restrictions on university entry, as previously mentioned, had become more in favour of people from wealthy backgrounds, as those with limited financial means were less likely to undertake study if the costs were high, or in the knowledge that they might not have a job — and thus the financial means to support themselves — in the profession of their choice once they graduated (Ringer, Citation2004: 235).

Such an ‘equilibrium’ view points to a functionalist understanding of social systems, whereby developments within a system are thought to balance each other out to produce a state of ‘normality’ or ‘order’ (Strasser & Randall, Citation1981: 80–81; Turner, Citation1978: 25–26). However, since this article has shown that higher education does not appear to have a ‘normal’ or orderly state, only fluctuations between periods of inclusive and exclusive access, perhaps a more apt description would be of higher education as a ‘tension-management system’ in which change does not restore any sense of ‘order’ to the system but is instead both the result and cause of tension production and reduction within that system (Moore, Citation1963: 10–11). ‘Tensions’, in this case, are the points of inclusivity and exclusivity that result from contextual developments. Such changes in circumstance can be seen in the shift in university admissions during the mid-nineteenth century — in Germany and France especially — when, after a long period of regarding universities as highly exclusive places to which admission was restricted, a scarcity in the number of skilled professionals gave rise to increased demand for people with a university education. This increased demand, in turn, saw access to higher education expand, right up to World War I (WWI) (Ringer, Citation2004: 235; Titze, Citation1987: 362). During this time, distance education also emerged and flourished, following the advent of correspondence courses in Britain in 1840 after the introduction of the British Postal Service (Guri-Rosenblit, Citation2005: 469; Rumble, Citation2001: 31). Here, and elsewhere soon after, we see the prospect of studying anywhere, anytime first make its way into public discourse, ensuring that campus-based and restricted delivery of university courses, once again, was not the be-all and end-all of higher education (Casey, Citation2008: 46; Rumble, Citation2001: 41; Sumner, Citation2000: 274–75).

Contraction and expansion: universities during and after the two world wars

Faced with the onslaught of both WWI and World War II (WWII), universities once again experienced a profound change in operations, as hoards of students and able staff enlisted for military service (Hammerstein, Citation2004; Willis, Citation1991: 18–20). Older staff, ineligible for combat, stayed behind to help with the war effort through research and development in areas such as explosives, chemical warfare, and cryptography (Scott, Citation2006: 28; Shils, Citation1992: 1264). In the aftermath of WWI, amidst political instability, many universities were left to rebuild their constituency from a severely diminished cohort of young people, with many having died in battle (Shils, Citation1992: 1265; Winter, Citation1977). Then, after the devastation of the subsequent war, WWII, the West experienced a new-found lease of life which subsequently spread throughout the globe. As well as the need to train a new workforce for the post-war era, a progressive mentality emerged, emphasising equality and human rights, as outlined in the then newly-established United Nation’s Universal Declaration of Human Rights (Husén, Citation1991: 173). This democratic sentiment promoted, once again, an emphasis on greater access to university education (Altbach, Citation1996: 24). Around the world, universities soon underwent significant expansion, or ‘massification’, to increase participation by broader sectors of society, especially ethnic minorities and women, as well as those from the lower classes for whom university was previously unavailable or unaffordable (Hussey & Smith, Citation2010: 1; Ringer, Citation2004: 257; Schofer & Meyer, Citation2005: 903; Siemens & Matheos, Citation2010; Teichler, Citation1998).

Not everyone was happy with the notion of increasing access to university education in the name of democracy, with conservative male alumni being the most vocal opponents (Geiger, Citation2009: 291; McCluskey & Winter, Citation2012: 48). For the vast majority, however, universities in the mid-twentieth century were in charge of dismissing previous notions of exclusivity and individualisation deemed responsible for bringing about not only two world wars, but also considerable economic turmoil through the Great Depression (Schofer & Meyer, Citation2005: 902). The impulse to widen university access in this post-WWII period, in contrast, was heavily geared towards egalitarianism, community, and social integration (Delanty, Citation2002: 44; Shils, Citation1992: 1268).

With increasingly more people subsequently attending university than ever before, the responsibilities and demands on university education and academic research grew considerably (Scott, Citation2006: 28; Shils, Citation1992: 1267). Once again, heavy public investment in universities saw a renewed state interest in university operations, but this time the emphasis was on accountability and administration (Shils, Citation1992: 1268; Zumeta, Citation2005: 6). Increases in size and bureaucratisation of universities inevitably gave them an even bigger public service function than they had held in the past, as well as other emerging responsibilities outside the realms of teaching, training, and research (Perkins, Citation1972; Shils, Citation1992: 1269).

Perhaps one of the biggest unintended consequences of the hasty expansion of access to university education in the 1960s was growing dissatisfaction among a disenchanted youth population (Boudon, Citation1982: 47–76; Husén, Citation1991: 179). Since this period of expansion was more about an ideological reaction to the horrors of war and genocide than a concerted response to specific economic need, it is no wonder that many people became frustrated with the lack of tangible benefit that university education was supposed to create (Schofer & Meyer, Citation2005: 900). For them, universities were failing to ensure that higher education would lead to greater social mobility and career prosperity (Kemp, Citation2012: 122). As a result, student protest movements began to emerge, the sentiments of which have had a lasting impact on how people view the value and relevance of university education today (Barnett, Citation1990: 25; Rochford, Citation2006: 156).

The post-WWII era was also important for another reason: the growth and legitimisation of distance education (Sumner, Citation2000: 274–75). Building on the previous correspondence era in the nineteenth century and the educational radio broadcasts from the 1920s and 1940s, television became the next technology to aid the delivery of higher education (Casey, Citation2008: 46; Rumble, Citation2001: 32). In the USA, for example, millions of people tuned in to ‘Sunrise Semester’, a televised coursework programme coordinated by New York University and the US television network, CBS, airing from 1957 to 1982 (Kim, Citation2013). As Kim (Citation2013) suggests, this is arguably one of the most obvious precursors to MOOCs: courses available to be viewed by hundreds of thousands, or even millions, of people in different locations, at the same time, where content was provided for free, and credit was provided for a fee. Taking this idea a step further was the UK’s Open University (OU), founded in 1969 with the intention of providing a new type of distance education — one that was mediated by newly emerged communication technologies, namely portable video and audio cassettes and, to some extent, the computer (Issroff & Scanlon, Citation2002; Rumble, Citation2001: 32; Sumner, Citation2000: 276). While not the first university to provide distance education, the OU was one of the most celebrated pioneers of this new technologically-mediated, open-education model; regarded by many as the first real attempt to create a formal, boundless university (Rumble, Citation2001: 36–37). Although it was met with significant initial distrust, it has since built a significant reputation and presence as Europe’s largest university (Sclater, Citation2008: 2; Open University, Citation2005).

Universities today: the latest concerns regarding access, exclusivity, and place in higher education

By the 1990s, developing and industrialised countries alike were struggling to sustain or improve the quality of higher education amidst ever-increasing enrolments and declines in public funding (Altbach, Citation1998: 352; Bundy, Citation2006: 4; Johnstone, Citation1998). This progressively austere environment gave cause for the World Bank (Citation1994: 16) to claim that higher education at this time was ‘in crisis’ throughout the world. Although the proportion of public funding was greatly diminished in some cases, the drive for accountability and productivity from the state remained, or even increased (Alexander, Citation2000; Hooker, Citation1997: 23; Zumeta, Citation2005: 5). With public funding no longer a secure source of income, universities in many countries sought additional funds from alternative sources, such as private investors or tuition fees, in order to sustain the continued influx of students as well as remain responsive to, but also less reliant upon, the demands of the state (Kärkkäinen, Citation2006; OECD, 2003). Together, the culmination of circumstances has seen universities increasingly come to resemble commercial enterprises, driven, not by national interests or the public good, but by market value and the needs of paying consumers (Hayes & Wynyard, Citation2002; Readings, Citation1996; Slaughter & Rhoades, Citation2004). As a result, higher education has become known as a product to be bought and sold, rather than a valued social and intellectual experience in its own right (Bridgman & Willmott, Citation2007: 150–59; Slaughter & Rhoades, Citation2004). Universities, in turn, have become increasingly more complex places, charged with meeting greater demands under ever-more-limited means (Kezar, Citation2009: 9). Herein lies Kerr’s (2001) notion of a ‘multiversity’: an institution with multiple and often competing goals and demands for service, autonomy, profitability, and relevance (Barnett, Citation1990: 25–26; Scott, Citation2006: 29–30).

Part of the multidimensional aspect of contemporary universities are the multiple modes of delivery that they now offer. Since the 1970s, both distance and online education (an offshoot of distance education) have expanded throughout the world and overlapped considerably, as communication technologies have continued to advance, and become more accepted and available over time (Casey, Citation2008; Chau, Citation2010; Harasim, Citation2000). Nowadays, the internet is considered to be integral to both on and off-campus education (Capra, Citation2011: 288; Sumner, Citation2000: 277–78). Online education, in particular, has been proliferating at a great pace, not only enabling universities to expand their institutional reach and allowing students to overcome great geographic distances, but also lessening or eliminating the need for local students to set foot on campus altogether (Cavanagh, Citation2012: 215; Rumble, Citation2001: 32).

That students now have much more choice in how they access their education means the line between ‘internal’ (on-campus) and ‘external’ (off-campus) students is becoming increasingly blurred, if not an altogether redundant distinction (Gosper et al., Citation2010: 259). This increased flexibility, in turn, has enabled greater access to higher education among a growing body of ‘non-traditional’ students, who tend to be older, working, and have families, and thus have other priorities competing for their time (Larreamendy-Joerns & Leinhardt, Citation2006: 570–71; Pepicello, Citation2012: 133). As such, while online education technologies are still regarded by some as unconventional or even undesirable, they have helped open up the prospect of higher education to a whole new generation of learners as something that is not only more accessible, but also more relevant and customised to their lifestyles (Bejerano, Citation2008).

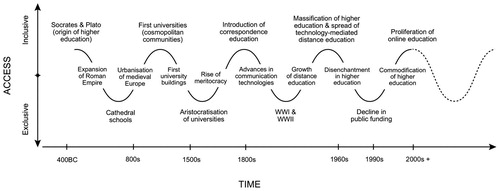

The issue of the relevance of university education, as this article has shown, is not a new one and neither are many of the contemporary debates around how universities operate (McCluskey & Winter, Citation2012: 36–37). And yet, today’s universities are still regarded as having a particularly confused mindset, with competing priorities and, therefore, no clear sense of purpose (Clark, Citation1983: 18; Cobban, Citation1992: 1245; Jongbloed et al., Citation2008: 304; McCluskey & Winter, Citation2012). Despite this confusion, contemporary universities remain part of the broadly conceived higher education system, a system that encompasses global trends and common historical roots (Altbach, Citation1996: 21–23). It is precisely because they are part of this system, which is capable of responding to tension, that universities have been able to survive over time. Key tension points within the system are illustrated in , which shows how higher education has experienced various stages of inclusive and exclusive access, increasing or decreasing alongside changes in social and technological conditions. As outlined in the purpose and scope of this article, such developments, while emerging from the West, can be conceived as part of the general global developments in the system of higher education over time. Viewed as a whole, this historical trajectory represents the prehistory of MOOCs and shows the historical antecedents of their emergence.

Figure 1. Note: Dates shown are selective and intended to provide context to the diagram; not to scale.

Historical trajectory of higher education, showing key points of tension (periods of inclusivity and exclusivity) over time.

While universities nowadays are highly diverse, both within and between countries, questions still remain as to what the future will bring, and whether this cyclical trend of tension management will continue into the future. MOOCs, as the latest tension within the higher education system, may well be conceived as part of the continuing proliferation of online education since the beginning of the new millennium; or, they may turn out to be part of the trend towards exclusion that — if previous history is anything to go by — will inevitably follow. Only time will tell their true place on the accessibility spectrum. At the very least, however, it is clear that MOOCs currently do not appear to represent a systemic break from higher education or a cause for destruction. Instead, they, and the rhetoric that surrounds them, maintain historical continuity with the cyclical evolution between inclusive and exclusive access that has occurred in the past.

Looking to the future, administrators and staff from both private and public universities around the world have begun to ask how they will respond to the continuing expansion of MOOCs, as well as the availability of new communication technologies and knowledge-sharing methods (Lakshminarayanan, Citation2012; Lawton & Katsomitros, Citation2012). A key issue is whether they will invoke a wholesale shift to the ‘boundless’ model of university education offered by fully online delivery, or whether they will re-affirm the so-called ‘traditional’ on-campus experience. Underlying this issue is the question of whether university education of the future should be ‘place-based’, that is, tied to a particular student body at a physical campus; or, ‘placeless’, with even the world's most prestigious universities accessible online anywhere, anytime, and to anyone (Holt & Challis, Citation2007; Rochford, Citation2006: 150).

Conclusion

This historical analysis has shown that there is a strong degree of familiarity in the rhetoric surrounding the uprooting and egalitarian potential of MOOCs and a sense that neither sentiment is entirely new. Current debates around the potential for MOOCs to ‘expand’ or ‘destroy’ prestigious universities, or do away with ‘traditional’ place-based higher education altogether, all ignore the fact that universities did not have elite origins, nor did they originate as ‘places’. Instead, ideas about the importance of place and campus life appear to be linked to changing social conditions and technologies, as well as varying attitudes and policies about higher education over time. Regardless of whether they are ultimately a democratising force or an instrument of elitism, MOOCs, as they currently appear, are the latest point of tension in the cyclical evolution between inclusivity and exclusivity in higher education and changing attitudes about what a university actually is or should be: an open community of scholars or an enclosed place of learning, teaching, and research. Therefore, rather than representing a break from what can be broadly conceived as the system of higher education — as the doomsayers suggest — MOOCs, at least in their current form, fit perfectly well within its historical trajectory.

Given the space constraints of this article, and the expansive nature of the history of higher education, there was a necessary degree of generality imposed on the analysis herein. A larger research project on the prehistory of MOOCs, therefore, could prove useful in interrogating and expanding on the trends discussed. Also worthwhile would be an analysis which compares and contrasts these observations with developments in non-Western countries, such as India — the second-biggest consumer of MOOCs (Mishra, Citation2013) — or China — predicted to become another prominent player in this space (Lapowsky, Citation2013; Li & Ye, Citation2013). An alternative complement to this kind of historical analysis of the heritage of MOOCs would be an examination of their future implications. Areas of emphasis in this space could include the impact of MOOCs on students (learning experience, access to higher education, etc.), on academics (teaching experience, career prospects, professional autonomy, etc.), on universities (purpose, relevance, authority over knowledge, etc.), and on the conceptualisation and configuration of higher education generally.

While this article has used MOOCs as the starting point for a historical review of inclusive and exclusive access in higher education, it is impossible to predict whether future developments will mean that MOOCs will continue to be absorbed by the system, or whether eventually they will break away or destroy it. Nonetheless, an awareness of the history of universities and parallel ideas about inclusivity and exclusivity in higher education, as outlined in this article, no doubt provides important insights for further investigation into this area and, indeed, all of the other topics proposed here. It also provides food for thought to all the MOOC champions, sceptics, and doomsayers currently dominating this space.

Notes on contributor

Emily Longstaff is a Sociology PhD candidate at the Australian National (ANU). She has a Bachelor of Arts with First Class Honours in Sociology, also from ANU, as well as a Master of Cross-disciplinary Art and Design from the University of New South Wales. It was during her master's degree, which she completed fully online while working as an education data analyst at the Australian Bureau of Statistics, that Emily garnered an interest in online education. This interest has since formed the basis for her PhD research into Massive Open Online Courses.

Correspondence to: Emily Longstaff, School of Sociology, College of Arts and Social Sciences, Australian National University, Canberra ACT 0200, Australia. Email: [email protected]

References

- Alexander FK. 2000. The Changing Face of Accountability: Monitoring and Assessing Institutional Performance in Higher Education. The Journal of Higher Education, 71(4): 411–31.

- Altbach PG. 1996. Patterns in Higher Education Development: Towards the Year 2000. In: Z. Morsy & P.G. Altbach, eds. Higher Education in an International Perspective: Critical Issues. New York & London: Garland, pp. 21–35.

- Altbach PG. 1998. Comparative Perspectives on Higher Education for the Twenty-First Century. Higher Education Policy, 11(4): 347–56.

- Andrews M. 2013. Unbundling … and Reinforcing the Hierarchy? Inside Higher Ed., 27 March [accessed 2 April 2013]. Available at: <http://www.insidehighered.com/blogs/stratedgy/unbundling-and-reinforcing-hierarchy>.

- Aslanian CB & Clinefelter DL. 2012. Online College Students 2012: Comprehensive Data on Demands and Preferences. Louisville, KY: Learning House & Aslanian Market Research.

- Bady A. 2013. The MOOC Moment and the End of Reform. The New Inquiry, 15 May [accessed 16 May 2013]. Available at: <http://thenewinquiry.com/blogs/zunguzungu/the-mooc-moment-and-the-end-of-reform>.

- Barber M, Donnelly K & Rizvi S. 2013. An Avalanche is Coming: Higher Education and the Revolution Ahead. London: Institute for Public Policy Research.

- Barnett R. 1990. The Idea of Higher Education. Buckingham: Society for Research into Higher Education & Open University Press.

- Bejerano AR. 2008. The Genesis and Evolution of Online Degree Programs: Who Are They For and What Have We Lost along the Way? Communication Education, 57(3): 408–14.

- Bender T. 1988. Introduction. In: T. Bender, ed. The University and the City: From Medieval Origins to the Present. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 3–10.

- Benson HH. 2011. Socratic Method. In: D.R. Morrison, ed. The Cambridge Companion to Socrates. Cambridge & New York: Cambridge University Press, pp. 179–200.

- Boudon R. 1982. The Unintended Consequences of Social Action. New York: St Martin’s Press.

- Brooks, D. 2012, 3 May. The Campus Tsunami. The New York Times. Retrieved 7 March 2013 from http://www.nytimes.com/2012/05/04/opinion/brooks-the-campus-tsunami.html.

- Bridgman T & Willmott H. 2007. Academics in the ‘Knowledge Economy’: From Expert to Intellectual? In: A. Harding, A. Scott, S. Laske & C. Burtscher, eds. Bright Satanic Mills: Universities, Regional Development and the Knowledge Economy. Hampshire & Burlington: Ashgate, pp. 149–60.

- Bundy C. 2006. Global Patterns, Local Options? Changes in Higher Education Internationally and Some Implications for South Africa Kagisano: Ten Years of Higher Education under Democracy. Pretoria: Council on Higher Education, pp. 1–20.

- Byrd MD. 2001. Back to the Future for Higher Education: Medieval Universities. Internet and Higher Education, 4(1): 1–7.

- Capra T. 2011. Online Education: Promise and Problems. MERLOT Journal of Online Learning and Teaching, 7(2): 288–93.

- Casey DM. 2008. A Journey to Legitimacy: The Historical Development of Distance Education through Technology. TechTrends, 52(2): 45–51.

- Cavanagh TB. 2012. The Postmodality Era: How ‘Online Learning’ is Becoming ‘Learning’. In: D.G. Oblinger, ed. Game Changers: Education and Information Technologies. Boulder, CO: Educause, pp. 215–28.

- Chau P. 2010. Online Higher Education Commodity. Journal of Computing in Higher Education, 22(3): 177–91.

- Clark BR. 1983. The Higher Education System: Academic Organization in Cross-National Perspective. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Clarke ML. 1971. Higher Education in the Ancient World. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Cobban AB. 1975. The Medieval Universities: Their Development and Organization. London: Methuen & Co.

- Cobban AB. 1992. Universities: 1100–1500. In: B.R. Clark & G.R. Neave, eds. The Encyclopedia of Higher Education, Vol. II. Oxford & New York: Pergamon Press, pp. 1245–51.

- Corbeill A. 2001. Educating the Roman Republic: Creating Traditions. Leiden: Brill.

- Coulson A. 1996. Markets versus Monopolies in Education: The Historical Evidence. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 4(9): 1–28.

- Coursera. 2013. About Coursera [accessed 20 October 2013]. Available at: <https://www.coursera.org/about>.

- Craig R. 2012. Elitism, Equality and MOOCs: Massive Open Courses Aren’t Answer to Reducing Higher Ed Inequality. Inside Higher Ed., 31 August [accessed 6 March 2013]. Available at: <http://www.insidehighered.com/views/2012/08/31/massive-open-courses-arent-answer-reducing-higher-ed-inequality-essay>.

- Davis PC & Steinglass EE. 1997. A Dialogue about Socratic Teaching. N.Y.U. Review of Law & Social Change, 23(2): 249–79.

- Delanty G. 2002. Challenging Knowledge: The University in the Knowledge Society. Buckingham: Society for Research into Higher Education & Open University Press.

- Dewald J. 1996. The European Nobility, 1400–1800. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Dillon J. 2003. The Heirs of Plato: A Study of the Old Academy (347–274 bc). Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- di Simone MR. 1996. Admission. In: H. de Ridder-Symoens, ed. A History of the University in Europe, Vol. II: Universities in Early Modern Europe (1500–1800). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 285–325.

- Durkheim E. 1977 [1904–05]. The Evolution of Educational Thought, trans. by P. Collins. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- edX. 2013. How It Works [accessed 20 October 2013]. Available at: <https://www.edx.org/how-it-works>.

- Fehl NE. 1962. The Idea of a University in East and West. Hong Kong: Chung Chi College.

- Frijhoff W. 1992. Universities: 1500–1900. In: B.R. Clark & G.R. Neave, eds. The Encyclopedia of Higher Education, Vol. II. Oxford & New York: Pergamon Press, pp. 1251–59.

- Frijhoff W. 1996. Graduation and Careers. In: H. de Ridder-Symoens, ed. A History of the University in Europe, Vol. II: Universities in Early Modern Europe (1500–1800). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 355–415.

- Gaebel M. 2013. EUA Occasional Papers: MOOCs — Massive Open Online Courses. Brussels: European University Association.

- Garrison DR & Kanuka H. 2004. Blended Learning: Uncovering its Transformative Potential in Higher Education. Internet and Higher Education, 7(2): 95–105.

- Geiger RL. 2009. The Ivy League. In: D. Palfreyman & T. Tapper, eds. Structuring Mass Higher Education: The Role of Elite Institutions. New York & London: Routledge, pp. 281–301.

- Gieysztor A. 1992. Management and Resources. In: H. de Ridder-Symoens, ed. A History of the University in Europe, Vol. I: Universities in the Middle Ages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 108–43.

- Gorski PS. 1999. Calvinism and State-Formation in Early Modern Europe. In: G. Steinmetz, ed. State/Culture: State-Formation after the Cultural Turn. New York: Cornwell University, pp. 147–81.

- Gosper M, McNeill M, Phillips R, Preston G, Woo K & Green D. 2010. Web-Based Lecture Technologies and Learning and Teaching: A Study of Change in Four Australian Universities. Journal of Research in Learning and Technology, 18(3): 251–63.

- Graves FP. 1910. A History of Education, Vol. II: During the Middle Ages and the Transition to Modern Times. New York: Macmillan.

- Guri-Rosenblit S. 2005. ‘Distance Education’ and ‘E-Learning’: Not the Same Thing. Higher Education, 49(4): 467–93.

- Hammerstein N. 2004. Universities and War in the Twentieth Century. In: W. Rüegg, ed. A History of the University in Europe, Vol. III: Universities in the Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries (1800–1945). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 637–672.

- Harasim L. 2000. Shift Happens: Online Education as a New Paradigm in Learning. Internet and Higher Education, 3(1–2): 41–61.

- Harden N. 2013. The End of the University as We Know It. The American Interest [accessed 6 March 2013]. Available at: <http://www.the-american-interest.com/article.cfm?piece = 1352>.

- Hayes D & Wynyard R, eds. 2002. The McDonaldization of Higher Education. Westport, CT: Bergin and Garvey.

- Highet G. 1976. The Classical Tradition: Greek and Roman Influences on Western Literature. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Holt D & Challis D. 2007. From Policy to Practice: One University’s Experience of Implementing Strategic Change through Wholly Online Teaching and Learning. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 23(1) [accessed 19 February 2013]. Available at: <http://www.ascilite.org.au/ajet/ajet23/holt.html>.

- Hooker M. 1997. The Transformation of Higher Education. In: D.G. Oblinger & S.C. Rush, eds. The Learning Revolution. Bolton: Anker Publishing, pp. 20–34.

- Husén T. 1991. The Idea of the University: Changing Roles, Current Crisis and Future Challenges. Prospects, XXI(2): 171–88.

- Hussey T & Smith P. 2010. The Trouble with Higher Education: A Critical Examination of Our Universities. New York: Routledge.

- Issroff K & Scanlon E. 2002. Educational Technology: The Influence of Theory. Journal of Interactive Media in Education, 6: 1–13.

- Jaschik S. 2013. MOOC Skeptic Proposes an Anti-MOOC MOOC. Inside Higher Ed., 20 May [accessed 22 May 2013]. Available at: <http://www.insidehighered.com/quicktakes/2013/05/20/mooc-skeptic-proposes-anti-mooc-mooc>.

- Jelley R & Scanlon C. 2013. Giving it Away for Free: Sharing Really is Caring in the Open Education Movement. The Conversation, 7 June [accessed 12 June 2013]. Available at: <http://theconversation.com/giving-it-away-for-free-sharing-really-is-caring-in-the-open-education-movement-14885>.

- Johnstone DB. 1998. The Financing and Management of Higher Education: A Status Report on Worldwide Reforms. Paper presented at the UNESCO World Conference on Higher Education, Paris [accessed 18 October 2013]. Available at: <http://www2.uca.es/HEURESIS/documentos/BMinforme.pdf>.

- Jongbloed B, Enders J & Salerno C. 2008. Higher Education and its Communities: Interconnections, Interdependencies and a Research Agenda. Higher Education, 56(3): 303–24.

- Kärkkäinen K. 2006. Emergence of Private Higher Education Funding within the OECD Area, September. OECD Centre for Educational Research and Innovation [accessed 18 October 2013]. Available at: <http://www.oecd.org/edu/skills-beyond-school/38621229.pdf>.

- Kemp P. 2012. The Idea of University in a Cosmopolitan Perspective. Ethics and Global Politics, 5(2): 119–28.

- Kerr C. 2001 [1963]. The Uses of the University, 5th edn. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Kezar A. 2009. Synthesis of Scholarship on Change in Higher Education. In: Mobilizing STEM Education for a Sustainable Future [accessed 3 February 2013]. Available at: <http://mobilizingstem.wceruw.org/documents/Synthesis%20of%20Scholarship%20on%20Change%20in%20HE.pdf>.

- Kim J. 2013. MOOC Pre-History. Inside Higher Ed., 4 June [accessed 12 June 2013]. Available at: <http://www.insidehighered.com/blogs/technology-and-learning/mooc-pre-history>.

- Kraut R. 2013. Plato. In: E.N. Zalta, ed. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Fall edn [accessed 16 August 2013]. Available at: <http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2013/entries/plato>.

- Lakshminarayanan S. 2012. Ruminating about MOOCs. Journal of the NUS Teaching Academy, 2(4): 223–27.

- Lapowsky I. 2013. MOOCs Try to Break the Language Barrier. Inc., 10 October [accessed 22 October 2013]. Available at: <http://www.inc.com/issie-lapowsky/mooc-providers-break-language-barrier.html>.

- Larreamendy-Joerns J & Leinhardt G. 2006. Going the Distance with Online Education. Review of Educational Research, 76(4): 567–605.

- Lawton W & Katsomitros A. 2012. MOOCs and Disruptive Innovation: The Challenge to HE Business Models. London: Observatory on Borderless Higher Education.

- Leach, L. 2013. Participation and equity in higher education: are we going back to the future? Oxford Review of Education, 39(2): 267–286.

- LeBlanc PJ. 2013. Thinking About Accreditation in a Rapidly Changing World. Educause Review, March/April: 48(2): 42–52.

- Leckhart, S. 2012, 20 March. The Stanford Education Experiment Could Change Higher Learning Forever. Wired. Retrieved 14 February 2013 from http://www.wired.com/wiredscience/2012/03/ff_aiclass/all/1.

- Lewin T. 2012. Instruction for Masses Knocks Down Campus Walls. New York Times, 4 March [accessed 7 March 2013]. Available at: <http://www.nytimes.com/2012/03/05/education/moocs-large-courses-open-to-all-topple-campus-walls.html?pagewanted = all>.

- Lewis CT & Short C. 1933. A Latin Dictionary. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Li X & Ye X. 2013. Massive Free Online Teaching the Next Big Thing in China. Shanghai Daily, 8 April [accessed 8 April 2013]. Available at: <http://english.peopledaily.com.cn/8198109.html>.

- Marklein MB. 2012. College May Never Be the Same. USA Today, 12 September [accessed 7 March 2013]. Available at: <http://usatoday30.usatoday.com/news/nation/story/2012/09/12/college-may-never-be-the-same/57752972/1>.

- Marrou HI. 1956. A History of Education in Antiquity. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

- Martin TR. 2000. Ancient Greece: From Prehistoric to Hellenistic Times. Yale Nota Bene. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Matkin GW. 2012. The Opening of Higher Education. Change, May/June [accessed 18 July 2013]. Available at: <http://www.changemag.org/Archives/Back%2020Issues/2012/May-June%202012/Higher%202020Ed.full.html>.

- McCluskey FB & Winter ML. 2012. The Idea of the Digital University: Ancient Traditions, Disruptive Technologies and the Battle for the Soul of Higher Education. Washington, DC: Westphalia Press.

- Miller T. 2012. MOOCs Break Down Barriers to Knowledge. The Australian, 12 December [accessed 27 March 2013]. Available at: <http://www.theaustralian.com.au/higher-education/opinion/moocs-break-down-barriers-to-knowledge/story-e6frgcko-1226534770043>.

- Mishra A. 2013. Students Flock to MOOCs to Complement Studies. University World News, 8 June [accessed 12 June 2013]. Available at: <http://www.universityworldnews.com/article.php?story = 20130607104833762>.

- Monoson SS. 2000. Plato’s Democratic Entanglements: Athenian Politics and the Practice of Philosophy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Moore WE. 1963. Social Change. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

- Mulholland J. 2013. A Promise of Education for All. The Globe and Mail, 2 October [accessed 4 October 2013]. Available at: <http://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/national/education/when-will-the-world-learn-online/article14637561>.

- Müller RA. 1996. Student Education, Student Life. In: H. de Ridder-Symoens, ed. A History of the University in Europe, Vol. II: Universities in Early Modern Europe (1500–1800). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 326–54.

- Nails D. 2006. The Trial and Death of Socrates. In: S. Ahbel-Rappe & R. Kamtekar, eds. A Companion to Socrates. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 5–20.

- Nails D. 2009. Socrates. In: E.N. Zalta, ed. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Spring 2010 edn [accessed 29 June 2013]. Available at: <http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2010/entries/socrates>.

- Oakeshott M. 2004. The Idea of a University. Academic Questions, 17(1): 23–30.

- Open University. 2005. History of The Open University [accessed 30 May 2013]. Available at: <http://www.mcs.open.ac.uk/80256EE9006B7FB0/%28httpAssets%29/F4D49088F191D0BF80256F870042AB9D/$file/History+of+the+Open+University.pdf>.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2003). Education Policy Analysis. Paris: OECD Publishing.

- Papenhausen C. 2009. A Cyclical Model of Institutional Change. Foresight, 11(3): 4–13.

- Pappano L. 2012. The Year of the MOOC. New York Times, 11 November [accessed 28 February 2013]. Available at: <http://www.nytimes.com/2012/11/04/education/edlife/massive-open-online-courses-are-multiplying-at-a-rapid-pace.html?pagewanted = all&_r = 0>.

- Pattyn B. 2006. Knowledge in the Past Tense: On the History of the Moral Status of Academic Knowledge. Ethical Perspectives, 13(2): 191–219.

- Pedersen O. 2000. The First Universities: Studium Generale and the Origins of University Education in Europe, trans. by R. North. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Pepicello W. 2012. University of Phoenix. In: D.G. Oblinger, ed. Game Changers: Education and Information Technologies. Boulder, CO: Educause, pp. 133–44.

- Perkin H. 1984. The Historical Perspective. In: B.R. Clark, ed. Perspectives on Higher Education: Eight Disciplinary and Comparative Views. Berkeley & Los Angeles: University of California Press, pp. 17–55.

- Perkin H. 2006. History of Universities. In: J.J.F. Forest & P.G. Altbach, eds. International Handbook of Higher Education, Vol. 18. Dordrecht: Springer, pp. 159–205.

- Perkins JA. 1972. Organization and Functions of the University. The Journal of Higher Education, 43(9): 679–91.

- Perry M, Chase M, Jacob JR, Jacob MC & von Laue TH. 2007. Western Civilisation: Ideas, Politics & Society, 8th edn, Vol. III. Boston & New York: Houghton Mifflin.

- Plato. 2002 [380 bc]. Meno, trans. by J. Holbo & B. Waring [accessed 4 June 2013]. Available at: <http://www.ma.utexas.edu/users/rgrizzard/M316L_SP12/meno.pdf>.

- Power EJ. 1964. Plato’s Academy: A Halting Step Toward Higher Learning. History of Education Quarterly, 4(3): 155–66.

- Power EJ. 1991. A Legacy of Learning: A History of Western Education. Albany: State University of New York Press.

- Pritchard R. 1998. Institutional Lifecycles in British Higher Education. Tertiary Education and Management, 4(1): 71–80.

- Rait RS. 1969. Life in the Medieval University. London: Cambridge University Press.

- Readings B. 1996. The University in Ruins. Harvard, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Ringer F. 2004. Admission. In: W. Rüegg, ed. A History of the University in Europe, Vol. III: Universities in the Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries (1800–1945). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 233–67.

- Rochford F. 2006. Is there Any Clear Idea of a University? Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 28(2): 147–58.

- Rowe C. 2011. Self-Examination. In: D.R. Morrison, ed. The Cambridge Companion to Socrates. Cambridge & New York: Cambridge University Press, pp. 201–14.

- Rüegg W. 1992. Themes. In: H. de Ridder-Symoens, ed. A History of the University in Europe, Vol. I: Universities in the Middle Ages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 3–34.

- Rumble G. 2001. Re-Inventing Distance Education, 1971–2001. International Journal of Lifelong Education, 20(1/2): 31–43.

- Russell B. 1961. History of Western Philosophy. London: Unwin University Books.

- Savin-Baden M. 2000. Problem-Based Learning in Higher Education: Untold Stories. Buckingham: Open University Press.

- Schofer E & Meyer JW. 2005. The Worldwide Expansion of Higher Education in the Twentieth Century. American Sociological Review, 70(6): 898–920.

- Schofield M. 2008. Plato in His Time and Place. In: G. Fine, ed. The Oxford Handbook of Plato. Oxford & New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 36–62.

- Schwinges RC. 1992. Admission. In: H. de Ridder-Symoens, ed. A History of the University in Europe, Vol. I: Universities in the Middle Ages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 171–94.

- Sclater N. 2008. Large-Scale Open Source E-Learning Systems at the Open University UK Educause Center for Applied Research. Research Bulletin, 2008(12): 1–13.

- Scott JC. 2006. The Mission of the University: Medieval to Postmodern Transformations. The Journal of Higher Education, 77(1): 1–39.

- Shils E. 1992. Universities: Since 1900. In: B.R. Clark & G.R. Neave, eds. The Encyclopedia of Higher Education, Vol. II. Oxford & New York: Pergamon Press, pp. 1259–75.

- Shirky C. 2012. Napster, Udacity, and the Academy. Shirky.com, 12 November [accessed 26 February 2013]. Available at: <http://www.shirky.com/weblog/2012/11/napster-udacity-and-the-academy>.

- Sichel BA. 1996. Socrates. In: J.J. Chambliss, ed. Philosophy of Education: An Encyclopedia. New York: Garland Publishing, pp. 615–16.

- Siemens G. 2012. Adjacent Possible: MOOCs, Udacity, edX, Coursera. In: xED Book, 4 November [accessed 7 March 2013]. Available at: <http://www.xedbook.com/?p = 81>.

- Siemens G & Matheos K. 2010. Systemic Changes in Higher Education. In Education, 16(1) [accessed 30 May 2013]. Available at: <http://ineducation.ca/article/systemic-changes-higher-education>.

- Simmons, R. 2002. Reinventing Education: From the Elite to the Unlimited. The Presidency, 5(2): 16–22.

- Slaughter S & Rhoades G. 2004. Academic Capitalism and the New Economy. Baltimore, MA: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Spies P. 2000. University Traditions and the Challenge of Global Transformation. In: S. Inayatullah & J. Gidley, eds. The University in Transformation: Global Perspectives on the Futures of the University. Westport, Connecticut: Bergin & Garvey, pp. 19–29.

- Strasser H & Randall S, eds. 1981. An Introduction to Theories of Social Change. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Sumner J. 2000. Serving the System: A Critical History of Distance Education. Open Learning, 15(3): 267–85.

- Teichler U. 1998. Massification: A Challenge for Institutions of Higher Education. Tertiary Education and Management, 4(1): 17–27.

- Tight M. 2012. Researching Higher Education, 2nd edn. Berkshire: Society for Research into Higher Education & Open University Press.

- Titze H. 1987. The Cyclical Overproduction of Graduates in Germany in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries. International Sociology, 2(4): 349–71.

- Turner JH. 1978. The Structure of Sociological Theory. Homewood, IL: Dorsey Press.

- Tweed RG & Lehman DR. 2002. Learning Considered within a Cultural Context: Confucian and Socratic Approaches. American Psychologist, 57(2): 88–99.

- Tweed RG & Lehman DR. 2003. Confucian and Socratic Learning. American Psychologist, 58(2): 148–49.

- Udacity. 2013. How It Works [accessed 20 October 2013]. Available at: <https://www.udacity.com/how-it-works>.

- van Werveke H. 1965. The Rise of the Towns. In: M.M. Postan, E.E. Rich & E. Miller, eds. The Cambridge Economic History of Europe from the Decline of the Roman Empire: Economic Organisation and Policies in the Middle Ages, Vol. III. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 1–41.

- Verger J. 1992. Patterns. In: H. de Ridder-Symoens, ed. A History of the University in Europe, Vol. I: Universities in the Middle Ages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 35–74.

- Walsh T. 2011. Unlocking the Gates: How and Why Leading Universities are Opening Up Access to Their Courses. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Wang H. 2010. The Influence of the Socratic Tradition on Cambridge Practice and Its Implication on Chinese Higher Education. Journal of Cambridge Studies, 5(1): 1–18.

- Weissmann J. 2012. The Single Most Important Experiment in Higher Education. The Atlantic, 18 July [accessed 26 February 2013]. Available at: <http://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2012/07/the-single-most-important-experiment-in-higher-education/259953/#.UAazxPuOSuc.email>.

- Willis R. 1991. Total War and Twentieth Century Higher Learning: Universities of the Western World in the First and Second World Wars. Cranbury, NJ: Associated University Press.

- Winter JM. 1977. Britain’s ‘Lost Generation’ of the First World War. Population Studies: A Journal of Demography, 31(3): 449–66.

- Woodruff P. 2011. Socrates and the New Learning. In: D.R. Morrison, ed. The Cambridge Companion to Socrates. Cambridge & New York: Cambridge University Press, pp. 91–110.

- World Bank. 1994. Higher Education: The Lessons of Experience. Washington, DC: International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/World Bank.

- Young S. 2013. Massive Open Online Courses Creating a ‘True Democratization of Education’. Argus Leader, 11 May [accessed 13 May 2013]. Available at: <http://www.argusleader.com/article/20130510/UPDATES/130510024/Massive-open-online-courses-creating-true-democratization-education-?nclick_check = 1>.

- Zeller E. 1876. Plato and the Older Academy, trans. by S.F. Alleyne & A. Goodwin. London: Longmans, Green & Co.

- Zumeta W. 2005. Public University Accountability to the State in the Late Twentieth Century: Time for a Rethinking? Review of Policy Research, 15(4): 5–22.