Abstract

Objective:

The increasing population of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected elderly patients results in a higher number of comorbidities and greater incidence of polypharmacy in addition to antiretroviral therapy (ART). The aim of this study is to describe the use of concomitant medication in older HIV-infected patients and to compare it with older general population.

Methods:

The study included HIV-positive outpatients (>49 years) who received ART in 2011. Co-medication dispensed by pharmacies in that year was collected. Defined daily dose (DDD) for each drug was calculated by patient. A comparison was made between the use of co-medication among men between 50 and 64 years old in general population against the HIV-infected population.

Results:

The study was based on 118 patients (77% men), of which 82% took at least one co-medication and 58% at least five. The commonest co-medications used by HIV-positive patients were antibiotics (44%); analgesics (44%); anti-inflammatories (39%); antacids (38%); and psycholeptics (38%). The medicines used for the greatest number of days per HIV-positive patient were those related to the renin–angiotensin system; anti-diabetics; lipid modifying agents; antithrombotics; and calcium channel blockers. In comparison with the general male population, a higher proportion of HIV-infected patients used antibiotics (42 vs 30%, P = 0.018), antiepileptics (16 vs 5%, P = 0.000), psycholeptics (35 vs 17%, P = 0.000) and COPD medications (14 vs 7%, P = 0.008). The duration of antibiotics and psycholeptic use in HIV-infected patients was longer compared to the general population (P < 0.05).

Conclusions:

Older HIV-positive patients frequently take a higher number of co-medication, which increases the risk of adverse events, interactions with other medication, and may lead to poorer treatment adherence.

Introduction

The prevalence of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection among people older than 50 years is increasing, due to new diagnostics and the chronicity of the illness. It has been estimated that by 2015, in the United States, 50% of HIV-infected patients will be aged 50 or over, a figure that is thought to be similar in other countries.Citation1 Research indicates that HIV-positive patients over the age of 50, who initiated antiretroviral therapy (ART), present the same virological response as those under 50, but the restoration of their immune system, both quantitative and qualitative, is worse and slower.Citation2 Furthermore, the HIV-infected population suffers a higher number of comorbidities at a younger age than the general population.Citation3–Citation5 All these reasons explain why the term “older” is used in HIV-positive patients over the age of 50.Citation3

Increasing age commonly results in a greater number of comorbidities and as a consequence a greater use of medication.Citation6 Polypharmacy produces decrease medication adherence and increase adverse drugs events and mortality.Citation7 There have been many studies on polypharmacy in the general population, particularly among the elderly, but few researchers have considered the situation with regard to HIV-positive patients. The HIV-infected population is more susceptible to harm from polypharmacy due to decrease organ system reserve, chronic inflammation, and ongoing immune dysfunction.Citation7

Liver and renal disease of older HIV-infected patients may modify the pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of many drugs, leading to toxicity and/or lack of efficacy of their treatments.

Recent studies have focused on the older HIV-positive patient subgroup and some have looked at the additional pharmacotherapy to ART,Citation1,Citation8–Citation11 but it is still unknown if there is a difference in the use of this co-medication between older HIV-infected patients and general population.

The aim of this study is to analyze the frequency of concomitant medication (co-medication) in the older HIV-positive patients with ART and to compare results between older male HIV-infected population and general population.

Materials and Methods

The study population included HIV-infected outpatients of 50 years old or over, who were receiving ambulatory ART from the Hospital Pharmacy of a university tertiary level hospital, between January and December 2011. The Hospital Pharmacy centralizes the collection of antiretroviral medication for all HIV-positive individuals from a specific geographic area, around the hospital: a total population of 306 064. In this way, all patients included are all possible in a given geographical area, similar to another one. Spanish population is covered by the public health system, so ART is given to every patient who needs it, which is dispensed by the Hospital Pharmacy.

We excluded patients enrolled in clinical trials, post-exposure prophylaxis and those whose data were not available.

Demographic variables (age, sex, country of origin) and variables related with HIV infection and ART was collected from medical notes and pharmacy dispensing records.

With regard to concomitant medication, we included all drugs dispensed by pharmacies with official medical prescription issued by the Aragonese Health Service and registered in the Aragonese Consumption of Pharmaceuticals Information System (the Farmasalud® database).

Ethical Committee for Clinical Research of Aragón issued a positive evaluation to this study, involved in the project “Antiretroviral Therapy used in HIV naive patients and used of concomitant medicines in older HIV-infected patients,” according to applicable law - RD223/2004 and Decree 26/2003 of Aragón Government, modified by Decree 292/2005.

In addition to the Ethical Committee approval, we received permission to access the Farmasalud database in an anonymized way.

We obtained details on co-medications issued to HIV-positive patients and the general population between January and December 2011. An individual was considered as having used a medicine when the database indicated that they had been issued with at least one medical prescription in the year of the study.

Medication was grouped according to the World Health Organization's Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification (ATC), to the second level of the therapeutic subgroup.Citation12 The defined daily dose (DDD) for each medication taken by each patient for the year was calculated. The DDD is the assumed average maintenance dose per day for a drug used for its main indication in adults. Defined daily doses are technical units of measurement created for use along with the ATC and are assigned to each chemical substance. The purpose of the ATC/DDD system is to serve as a tool for drug utilization research in order to improve quality of drug use. One component of this is the presentation and comparison of drug consumption statistics at international and other levels.

This study focused on DDD medications as defined by the WHO. Therefore, medicines without a DDD, such as creams, balms and nose or eye drops, were not included in the analysis.

The study population was classified by the number of different co-medications they had received during the year. Individuals that had been prescribed five or more co-medicines were classified as polymedicated patients. It is generally accepted that five different medications is the threshold associated with negative health outcomes.Citation7,Citation13–Citation15

The proportion of patients that were polymedicated and the proportion of patients who received each group of medication were calculated. Based on the DDD analysis, the median number of days of treatment with each medication was also calculated.

A comparative analysis was made of the use of co-medication by the male HIV-infected population and the general male population of 50–64 years old. The selection of the 50–64 age group was in line with other studiesCitation1 and also due to the small numbers of HIV-positive patients over 64 in our study population. The comparison was confined to men due to distribution differences between men and women with regard to the general population and the HIV-infected population, and differences between male and female use of medications that have been described in published literature.Citation8,Citation16,Citation17 The comparative analyses were carried out on the proportion of patients that had received each group of medication and the median days of treatment with each group of medication.

The statistical analysis

Data were expressed in frequencies and percentages of the qualitative variables and as a mean and range of the quantitative variables. The frequencies of the qualitative variables were compared using the Chi-squared test, and the comparison of means in quantitative variables that did not follow a normalized distribution was checked with the Mann–Whitney U test. The SPSS 15.0 licensed to the University of Zaragoza was used to analyze the data.

Results

A total of 130 HIV-positive individuals over 50 years of age received ART from the Pharmacy Service in 2011, representing 19.8% of all the HIV-infected patients who used the service. Data from 12 HIV-infected patients were not available, so these patients were excluded from the study. Finally, there were included 118 HIV-infected patients. The main characteristics of the study HIV-infected population are shown in ; 77% were men and 28% were co-infected with HCV.

Table 1. Characteristics of HIV-infected population ≥ 50 years old.

Older HIV-infected population

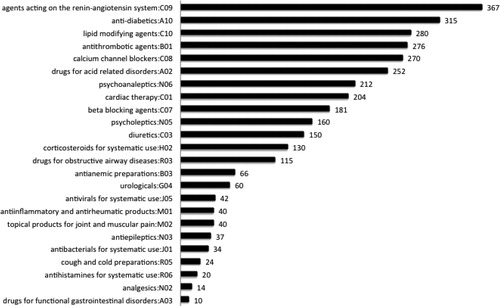

At least one concomitant medication to ART was received in 82.2% of HIV-infected patients and 57.6% had taken at least five co-medications, with a median of five (range of 0–24) ().

Figure 1. Number of concomitant medications taken by human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-positive patients ≥ 50 years old.

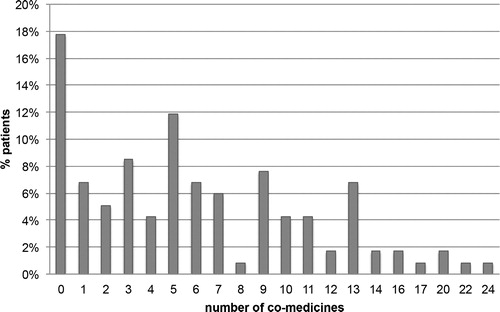

The medications used by a higher percentage of older HIV-positive patients, classified into therapeutic subgroups (ATC), were as follows: antibacterial for systematic use (J01) – taken by 44% of the patients; analgesics (N02) – 44%; anti-inflammatory and anti-rheumatic products (M01) – 39%; drugs for acid-related disorders (A02) – 38%; psycholeptics (N05) – 38%; cough and cold preparations (R05) – 30%; lipid modifying agents (C10) – 26%; agents acting on the renin–angiotensin system (C09) – 22%; antihistamines for systematic use (R06) – 20%; antiepileptics (N03) – 18%; and, drugs for obstructive airway diseases (R03) – 17%.

Medications that were most used in terms of the number of days per patient, based on the median DDD, are shown in . As might be expected, they are drugs for treatment of chronic pathologies: agents acting on the renin–angiotensin system (C09), 367 median days of treatment; anti-diabetics (A10), 315; lipid modifying agents (C10), 280; antithrombotic agents (B01), 276, and calcium channel blockers (C08), 270.

Comparison between HIV-positive and general population

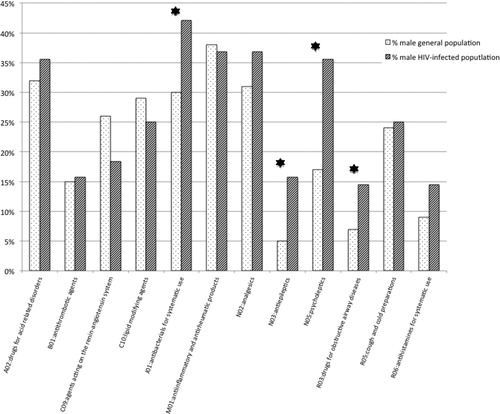

A comparison was made between the male HIV-infected population of 50–64 years old and the general male population of the same age range. There was a similar percentage that received at least one medication (79% general population, 80% HIV-infected population). A statistically significant higher percentage of HIV-positive patients used the following therapeutic subgroups comparing to general population: J01-antibacterials for systematic use (42.1 vs 29.7%, P = 0.018), N03 – antiepileptics (15.8 vs 5.0%, P = 0.000), N05 – psycholeptics (35.5 vs 16.6%, P = 0.000) and R03 – for obstructive airway diseases (14.5 vs 6.8%, P = 0.008) (). There were also higher numbers of estimated treatment days in the HIV-infected population, using the median DDD, with statistically significant differences, in the following groups: J01 – antibacterials for systematic use (25 vs 20, P = 0.01) and N05 – psycholeptics (180 vs 60, P = 0.0000). On the establishment of two groups based on duration of treatment of up to 90 days and more than 90 days, statistically significant differences were also observed between the HIV-infected group and the general population: 63.0% of HIV-positive patients taking psycholeptics were using the medication for more than 90 days compared with 41.8% of general population (P = 0.031) and 9.4% of the HIV-positive patients took antibacterials for more than 90 days, compared to 2.5% of the general population (P = 0.046).

Discussion

Using a definition of a medical treatment as the collection of a medical prescription from a pharmacy at least once in the year of the study, 82% of the older HIV-positive patients had received medication, in addition to their ART, in 2011. This figure is similar to Swiss cohort study of the same age rangeCitation9 and Shah's work, which was based on patients of over 55 years old.Citation18

With regard to polymedication, it should be noted that the published literature offers different definitions and cutoff points, although five medications is the generally accepted criterion.Citation10,Citation13–Citation15 In this study, 58% of the older HIV-infected patients were polymedicated, that is, taking five or more medications in addition to their ART. This result was coherent with the studies of Holtzman (54%) and Edelman (55%). Tseng et al. set the figure for polymedication as 4, and in that study 68.5% of the patients were polymedicated. When we tested our population at four medications, the result was 61.9%.Citation7,Citation10,Citation11

The medications used by the older HIV-infected population can be divided into two groups:

| (i) | Medicines taken for temporal, specific reasons, for limited time periods, such as analgesics, anti-inflammatories, cough and cold treatments, antibiotics, that are used by a high percentage of patients (44, 39, 30, and 44%, respectively) with low median estimated numbers of treatment days (14, 40, 24, and 34 days, respectively). | ||||

| (ii) | Medicines for chronic illnesses, such as lipid lowering agents and antihypertensive. These were used by a high percentage of patients and for longer durations. The use of this type of medication is linked to the fact that increased age augments the probability of comorbidities that include dyslipidemia, hypertension, cardiovascular disease (CVD), and diabetes.Citation1,Citation4,Citation10,Citation19–Citation21 | ||||

In our study of older HIV-positive patients, there were a much higher proportion of men than women (82%), similar to other studies on the older HIV-infected population (Marzolini – 80%, Onen – 83%, Holtzman – 83%). Furthermore, the literature has described sex differences with regard to pharmacotherapeutic profiles.Citation8,Citation14 For these reasons, we confined our comparison of HIV-positive patients and the general population to men between the ages of 50 and 64.

The fact that the antibiotic use differs between both populations may be a reflection of the nature of the HIV condition, which weakens the immune system and therefore requires more use of antibiotics, whether as acute treatment or as prophylaxis use. However, this population was not very immunocompromised, so this higher use could be due to an earlier use in order to avoid future complications. It is known that in some countries in Southern Europe, the use of antibiotics is quite common compared to Northern Europe, but in this study we are analyzing population of the same geographic area, so this item should not be affected.Citation16

The greater use of psycholeptics, such as alprazolam, sulpiride, and risperidone by the HIV-positive patients, compared with the general population, might be explained by a higher prevalence of psychiatric diseases, drug abuse, or dependence in this population.Citation19,Citation22

Given that CVD is one of the most frequent comorbidities among HIV-positive patients,Citation4,Citation20 we might have expected to observe differences with regard to the general population. However, this was not the case. A possible explanation could be that HIV-infected patients may have undertreated CVDs. Many characteristics of the two study groups are not known, so there are many other possible explanations such as a high level of primary chemoprophylaxis cardiovascular among the general male population of the same age range (50+), different rates of CVD or CVD risk factors such as smoking and dyslipidaemia.

One of the main differences between this study on the use of medications by HIV-positive patients and other similar works is the methodology employed for the collection of medication data. Most studies use data from patients’ clinical notes and/or interviews in which the individual lists the medications taken.Citation1,Citation8–Citation10 This could lead to bias or misinformation due to problems of memory;Citation23 data collection is cross-sectional. These methods have limitations and there is no clear evidence on the most adequate technique for reviewing patient treatments,Citation6,Citation7 differences that depend on the methodology employed have been noted.Citation17,Citation24 In our analysis, we took data from the pharmacies that had dispensed the medications in accordance with medical prescription. The data, therefore, reflect medication taken for both temporal and chronic conditions in addition to providing information on the collection of medication, which does not always coincide with the issuing of the prescription (due to adherence failure).

When comparing our study with others, consideration must be given to the different sources of information on medication, the criterion for polymedication, and the question of a transversal or longitudinal approach.

Another common limitation of studies that use the consumption of drugs dispensed by pharmacies as a source is that they only include data on medications of official medical prescriptions; they do not include private health system treatments or alternative medicines. However, this is not seen as a very significant limitation in our case; given the universal coverage of the public health system in Spain, with a small number using alternative sources for their medications.

The analysis of DDD consumption does not take into account the use of creams, ointments, or eye drops, but these products are much less relevant with regard to risk of pharmacological interaction.

Recent studies have examined medication interactions in the HIV-infected population and have demonstrated that there is a higher risk of interaction when a number of specific factors are present: protease inhibitor treatment, non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor treatment, recreational use of drugs, HCV coinfection, and the use of at least two medications in addition to ART, anxiety, dyslipidemia, and advanced age.Citation9–Citation11 The co-medications that the aforementioned authors found most implicated in interactions were treatments for CVDs and the central nervous system.Citation9,Citation11

It is very important to have a complete and accurate drug history prior to starting additional medications. When prescribing a new medication, healthcare providers should be careful to choose the most appropriate drug, paying attention to avoid combinations, which can lead to synergistic toxic effects, agreeing on a schedule of medications administration, reducing pill burden, and careful titration of medications.

The polymedicated population over 65 years old have a higher rate of hospital admission caused by adverse reactions to medicationsCitation15 and have a higher rate of mortality.Citation13,Citation14 It is important to increase our knowledge of polymedication among the increasing older HIV-infected population in order to be able to develop prevention strategies for the problems inherent in old age and multiple treatments.

An HIV specialist, although knowledgeable in the nuances of ART, may be less comfortable managing multiple age-related illnesses, so increasingly, they must be trained in geriatric issues.

There are some projects like HIV and Aging Consensus Project, which recommends treatment strategies for clinicians who manage HIV-infected older adults.Citation3 This work group recommends that individuals use either only one pharmacy or a pharmacy with an integrated computer network, and where possible, use a HIV-specialty pharmacy. Having a clinical pharmacist assist with prescriptions can help to reduce inappropriate prescribing and thereby decrease the rate of drug-related problems.

Conclusions

More than half the older HIV-positive patients in this study received five or more different medications, in addition to ART, in the 12-month study period. At least one-third had taken antibiotics, analgesics, anti-inflammatories, antacids, and/or psycholeptics. Medications for cardiovascular conditions and diabetes were most consumed in terms of the number of days per patient.

There are a higher number of estimated treatment days among the male HIV-infected population in comparison with the general male population with regard to the use of antibiotics and psycholeptics. In the other pharmacological groups, no statistically significant differences between the two populations were found.

The higher use of medications among the older HIV-infected population may reduce treatment adherence and consequently, effectiveness. It may also increase the risk of interactions and adverse events. This study has aimed to make a contribution to the body of knowledge on polypharmacy among the increasing numbers of older HIV-positive patients. We hope that this knowledge will help clinicians to evaluate the need for medication and to develop measures directed at reducing toxicity and improving treatment efficacy.

Acknowledgements

We thank Elena Rivero for final English revision.

Disclaimer Statements

Contributors

The corresponding author has designed the study, obtained ethics approval, collected the data, analyzed the data, interpreted the data, and written the article. The rest of the authors have contributed to design the study, collected the data, interpreted the data, and revised the article.

Funding

None.

Conflicts of interest

There is no conflict of interest.

Ethics approval

Ethical Committee for Clinical Research of Aragón has issued a positive evaluation to this study, involved in the project “Antiretroviral Therapy use of HIV naive patients and use of concomitant medicines in older HIV-infected patients”, according to applicable law – RD223/2004 and Decree 26/2003 of Aragón Government, modified by Decree 292/2005.

References

- Hasse B, Ledergerber B, Furrer H, Battegay M, Hirschel B, Cavassini M, et al. Morbidity and aging in HIV-infected persons: the swiss HIV cohort study. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53:1130–1139.

- Blanco JR, Jarrín I, Vallejo M, Berenguer J, Solera C, Rubio R, et al. Definition of advance age in HIV infection: looking for an age cut-off. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2012;28:1000–1006.

- Work Group for the HIV and Aging Consensus Project. Summary report from the human immunodeficiency virus and aging consensus project: treatment strategies for clinicians managing older individuals with the human immunodeficiency virus. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60:974–979.

- Guaraldi G, Orlando G, Zona S, Menozzi M, Carli F, Garlassi E, et al. Premature age-related comorbidities among HIV-infected persons compared with the general population. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53:1120–1126.

- Justice AC. HIV and aging: time for new paradigm. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2010;7:69–76.

- Gleason LJ, Luque AE, Shah K. Polypharmacy in the HIV-infected older adult population. Clin Interv Aging. 2013;8:749–763.

- Edelman EJ, Gordon KS, Glover J, McNicholl IR, Fiellin DA, Justice AC. The next therapeutic challenge in HIV: polypharmacy. Drugs Aging. 2013;30:613–628.

- Marzolini C, Elzi L, Gibbons S, Weber R, Fux C, Furrer H, et al. Prevalence of comedications and effect of potential drug-drug interactions in the Swiss HIV Cohort Study. Antivir Ther. 2010;15:413–423.

- Marzolini C, Back D, Weber R, Furrer H, Cavassini M, Calmy A, et al. Ageing with HIV: medication use and risk for potencial drug-drug interactions. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66:2107–2111.

- Holtzman C, Armon C, Tedaldi E, Chmiel JS, Buchacz K, Wood K, et al. Polypharmacy and risk of antiretroviral drug interactions among the aging HIV-infected population. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;10:1302–1310.

- Tseng A, Szadkowski L, Walmsley S, Salit I, Raboud J. Association of age with polypharmacy and risk of drug interactions with antiretroviral medications in HIV-positive patients. Ann Pharmacother. 2013;47:1429–1439.

- WHOCC. WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology, ATC classification index with DDDs. Oslo www.whocc.no/atc_ddd_index/. Accessed June, 2012 2012.

- Gnjidic D, Hilmer SN, Blyth FM, Naganathan V, Waite L, Seibel MJ, et al. Polypharmacy cutoff and outcomes: five or more medicines were used to identify community-dwelling older men at risk of different adverse outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol. 2012;65:989–995.

- Richardson K, Ananou A, Lafortune L, Brayne C, Matthews FE. Variation over time in the association between polypharmacy and mortality in the older population. Drugs Aging. 2011;28:547–560.

- Marcum ZA, Amuan ME, Hanlon JT, Aspinall SL, Handler SM, Ruby CM, et al. Prevalence of unplanned hospitalizations caused by adverse drug reactions among older veterans. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60:34–41.

- Malo-Fumanal S, Rabanaque-Fernández MJ, Feja-Solana C, Lallana-Alvarez MJ, Armesto-Gómez J, Bjerrum L. [Differences in outpatient antibiotic use between a Spanish region and Nordic country]. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2014;32:412–417.

- Aguilar-Palacio I, Carrera-Lasfuentes P, Poblador-Plou B, Prados-Torres A, Rabanaque-Hernández MJ. [Morbidity and drug consumption. Comparison of results between the National Health Survey and electronic medical records]. Gac Sanit. 2014;28:41–47.

- Shah SS, McGowan JP, Smith C, Blum S, Klein RS. Comorbid conditions, treatment, and health maintenance in older persons with human immunodeficiency virus infection in New York City. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;35:1238–1243.

- Goulet JL, Fultz SL, Rimland D, Butt A, Gibert C, Rodriguez-Barradas M, et al. Do patterns of comorbidity vary by HIV status, age, and HIV severity? Clin Infect Dis. 2007;15:1593–1601.

- Onen NF, Overton ET, Seyfried W, Stumm ER, Snell M, Mondy K, et al. Aging and HIV infection: a comparison between older HIV-infected persons and the general population. HIV Clin Trials. 2010;11:100–109.

- Blanco JR, Caro AM, Pérez-Cachafeiro S, Gutiérrez F, Iribarren JA, González-García J, et al. HIV infection and aging. AIDS Rev. 2010;12:218–230.

- Justice AC, McGinnis KA, Atkinson JH, Heaton RK, Young C, Sadek J, et al. Psychiatric and neurocognitive disorders among HIV-positive and negative veterans in care: Veterans Aging Cohort Five-Site Study. AIDS. 2004;1:S49–S59.

- Schmiemann G, Bahr M, Gurjanov A, Hummers-Pradier E. Differences between patient medication records held by general practitioners and the drugs actually consumed by the patients. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2012;50:614–617.

- Furler MD, Einarson TR, Walmsley S, Millson M, Bendayan R. Polypharmacy in HIV: impact of data source and gender on reported drug utilization. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2004;18:568–586.