Abstract

Objectives

During long term follow-up of a cohort of patients with essential thrombocythemia (ET) and polycythemia vera (PV) a higher than expected incidence of myelofibrosis (MF) was noted. In order to test if the explanation could be found in the diagnostic criteria a re-evaluation of diagnosis using the 2008 WHO diagnostic criteria for ET and MF was performed.

Methods

This prospective study of 60 patients with ET and PV was set up in 1998 to evaluate the long-term efficacy and tolerability of anagrelide treatment. Bone marrow trephine biopsies were requested from study start, after 2 and 7 years of follow-up. A blinded re-evaluation of the bone marrow trephines was performed. The 2008 WHO bone marrow criteria were used for diagnosis and fibrosis grading.

Results

Of 40 patients with an initial diagnosis of ET, 21 were confirmed as ‘true ET’ whereas 17 were reclassified as primary myelofibrosis (PMF) (12 PMF-0, 3 PMF-1, 2 PMF-2) and 2 as myeloproliferative neoplasms of uncertain origin. After 7 years of follow-up, 19 of 21 patients with ‘true ET’ were alive, none had transformed to MF, leukemia, or myelodysplastic syndrome. In contrast, 4/17 patients reclassified as PMF had died, two patients transformed to myelodysplastic syndrome and 7 patients progressed to overt MF.

Discussion

We conclude that a blinded re-evaluation of bone marrow trephines from study start and after 7 years of follow-up using 2008 World Health Organization criteria was able to differentiate between true ET and PMF with a marked difference in follow-up outcome.

Introduction

In the World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines, true essential thrombocythemia (ET) is distinguished from early-stage primary myelofibrosis (PMF).Citation1 The importance of distinguishing between these entities has been indicated by recent retrospective studies, showing that early PMF more often progresses to clinically overt myelofibrosis, and that prognosis is more severe for patients with early PMF.Citation2–Citation4 The negative impact of the presence of bone marrow fibrosis on prognosis with regard to overt myelofibrosis as well as survival has been confirmed in a recent retrospective study, where the WHO classification is not used but ET patients are grouped on the basis of bone marrow fibrosis grade.Citation5 According to the revised WHO 2008 classification of myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs), the main diagnostic tool to discriminate ET from early PMF is the identification of specific bone marrow patterns;Citation6,Citation7 however, the usefulness of the new WHO classification bone marrow criteria is under debate.Citation8–Citation11

Anagrelide, a non-cytostatic drug that selectively reduces the production of platelets by inhibiting megakaryopoiesis, is registered in Europe as second-line therapy for platelet reduction in ET in resistance or toxicity of hydroxyurea (HU). Previous studies have shown that anagrelide effectively lowers platelet counts and reduces ET-associated complications.Citation12–Citation14 However, few studies have investigated the long-term efficacy and clinical toxicity of the drug.Citation15,Citation16

Since we were prospectively following up a cohort of patients in a study of anagrelide treatment, started in 1998, we saw the opportunity to investigate bone marrow status and survival in relation to a re-evaluation of diagnosis, using the new WHO diagnostic criteria. For the sake of completeness, we also report long-term efficacy and tolerability of anagrelide treatment. The median follow-up time period was 8.1 years; results after 2 years of follow-up were previously reported.

Methods

The study design for the first 2 years has been described elsewhere.Citation17 Briefly, this prospective non-comparative phase II clinical trial on anagrelide treatment included 60 patients with MPNs from 7 Swedish centers. At the time of study start 17 patients were diagnosed with polycythemia vera (PV), 42 with ET, and 1 with PMF. The diagnosis was made according to the diagnostic criteria of Kutti and WadenvikCitation18 for ET, and Pearson et al.Citation19 for PV, criteria very close to the diagnostic criteria according to the ‘Polycythemia Vera Study Group’ (PVSG). Patients with previous thromboembolic episodes or ongoing microcirculatory symptoms were accepted in the study with platelet counts >600 × 109/l (n = 25), and asymptomatic patients with platelet counts >1000 × 109/l (n = 35). Patients with clinically significant cardiac arrhythmia or cardiac failure were excluded. The analyses are based on 59 patients, 1 was lost to follow-up. The median age was 53.5 years and 58% of the patients were female.

All study subjects provided oral and written informed consent before being enrolled. The study protocol was approved by the regional ethics committees and the Swedish Medical Products Agency. Comprehensive clinical information was collected prospectively including disease-related complications such as thromboses and hemorrhages as well as transformations. However, JAK2 mutational status, if available, was obtained at 7 years of follow-up. Side effects were recorded and graded I-IV according to the WHO grading scale. Both patients and doctors provided every 6th month during the 2 first years of the study and at 7 years of follow-up a global assessment of the efficacy and tolerability of the anagrelide treatment, using a 10-point visual analog scale.

Bone marrow trephines were requested at study start, after 2 years of follow-up and after 7 years of follow-up. Trephine biopsy sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin and Gordon and Sweets silver stain for reticulin. At the end of study the trephine specimens were reassessed by two experienced hematopathologists with a special interest in myeloproliferative disorders (HMK, JT). The examination was blinded, without the knowledge of time of sampling or any clinical data, except age and sex. WHO criteria were used for diagnosis and fibrosis grading (grade 0–3), where grades 0 and 1 are associated with early PMF.

Descriptive statistics were used to display the data. The χ2 of Fisher's exact test was used to compare categorical variables among groups, whereas the Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare continuous variables among groups. The statistical analysis was performed using the program PASW Statistics Version 18.

Results

Assessment of bone marrow fibrosis and re-evaluation of the diagnosis of ET

From study start there were bone marrow specimens of good quality from 40/42 patients with an initial diagnosis of ET. The concordance rate between the two pathologists when reviewing the bone marrow specimens was 95%. The blinded bone marrow analysis confirmed from the available 40 samples 21 as ‘true ET’ according to WHO criteria. Seventeen of the patients with the initial diagnosis ET were reclassified as PMF (12 PMF-0, 3 PMF-1, 2 PMF-2) and two as MPN of uncertain origin (MPN-U). The gender distribution and the median age did not differ between patients with ‘true ET’ and patients rediagnosed with early PMF (). The median time between the diagnosis of the MPN and study start was similar for ET and PMF, 5 and 7 months, respectively (P = 0.79), whereas the mean duration of ET was 2.8 years before study entrance and 2.4 years for PMF (P = 0.29). Approximately 40% in both groups had previously been treated with cytoreductive drugs. There were available JAK2V617F tests in 15/21 patients with ET, and 8 were positive (53%). In patients with PMF, JAK2V617F were available in 10/17, and only 1 was positive (10%). The difference in the JAK2 mutational status between ET and PMF was statistically significant (P = 0.04). At study start there were no significant differences between hemoglobin level or leukocyte counts in patients with ET and patients reclassified as PMF. There was a borderline statistical significant finding for a higher platelet count in PMF compared to ET and a tendency for a higher serum lactate dehydrogenase level ().

Table 1. Comparison of patient characteristics at study start in patients with ‘true ET’ versus rediagnosed early PMF

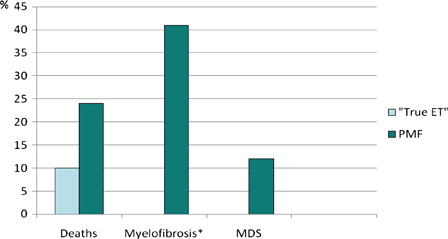

After a minimum of 7 years of follow-up, 19 of 21 patients with ‘true ET’ were alive. The two patients who died did so from non-MPN-related causes; one patient died from trauma and another from respiratory insufficiency. At follow-up 4/17 patients reclassified as PMF had died (1 stroke, 1 infection, 1 heart failure and 1 due to complications after stem cell transplantation). Two patients in the PMF group transformed to myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) during the study period and there were seven cases of reported progression into overt MF (WHO-criteria) (). None of the patients with ‘true ET’ transformed to leukemia, MDS, or MF during the study period, 0/21 vs. 9/17 in the PMF group (P = 0.002).

Figure 1. Reports of deaths and transformations to MDS and WHO-compatible myelofibrosis (%) during at least 7 years of follow-up in relation to new diagnosis after review of bone-marrow specimens. *WHO-compatible overt myelofibrosis; MDS: Myelodysplastic syndrome; ET: Essential thrombocytosis; PMF: primary myelofibrosis.

Among patients confirmed as ‘true, WHO-defined ET’, follow-up biopsies in 12 out of the 19 patients still alive were available; MF was not observed in any of those. Out of 13 patients alive reclassified as PMF, follow-up biopsies from 12 cases were available. Progression of fibrosis was commonly seen, and at study end nine biopsy specimens including seven derived from patients with early PMF showed a fibrosis grade of 2 or higher ().

Table 2. Grade of bone marrow fibrosis in 35 available bone marrow biopsies after at least 7 years of observation

In the group of patients reclassified as ‘true ET’ and with available follow-up biopsies 7/12 were still treated with anagrelide. Five patients had stopped treatment due to side effects and/or insufficient response. Treatment with anagrelide was maintained in 6/12 patients reclassified as PMF and available follow-up biopsies. The reasons for withdrawal were side effects in two cases and transformation to MF in four.

Frequency and type of cytoreductive treatment before study start did not differ between patients reclassified as PMF and ‘true ET’. Cytoreductive drugs were previously used in 41% and 38% of the patients in each group, respectively. HU was the most commonly used drug, and two patients from each group had received interferon. If combination therapy was initiated during the study period, anagrelide treatment was always combined with HU. Patterns of treatments chosen after withdrawal of anagrelide were similar in patients with ‘true ET’ compared to patients reclassified as PMF (with the exception of patients who had transformed to overt MF). Most patients started treatment with HU; occasional patients were treated with interferon, thalidomide, busulfan, or thioguanine.

In patients with PV there were biopsies of good quality from 15 out of 16 from study start. Three patients had a fibrosis grade of 1, the rest had no signs of fibrosis. Among the 14 patients still alive at study end 10 biopsies were available, and at that point 3 had grade 2 fibrosis and 2 had grade 1, while 5 patients had no fibrosis (). However, none had a WHO-compatible diagnosis of myelofibrosis. Four of the patients were still on anagrelide treatment after 7 years. None of these patients had any sign of fibrosis at study start but follow-up biopsies, available in three patients, showed progression of fibrosis in all three (grade 2 fibrosis in two and grade 1 in one patient).

Feasibility and hematological response after long-term anagrelide treatment

As previously reported, 30 patients had stopped treatment with anagrelide after 2 years of follow-up.Citation17 Most of the drop-outs occurred during the first 6 months of therapy. The most common causes of withdrawal were side effects or insufficient effect at tolerable doses. During the next/following 7 years another eight patients stopped treatment; however, in four of these patients anagrelide was restarted either alone or in combination with other cytoreductive drugs. Hence, at 7-year follow-up 22 patients with ET and 4 patients with PV were treated with anagrelide. Four of these patients had combination therapy with another cytoreductive drug. Nineteen of the 26 patients remaining on anagrelide had concomitant treatment with acetylsalicylic acid (ASA) at study end. The reason for withdrawal of anagrelide during years 3–7 in the study was side effects or insufficient effect in three patients and transformation to acute myeloid leukemia, MDS, or MF in five patients. More serious adverse reactions were reported in nine patients during the study period and included heart failure, pulmonary hypertension, cardiac arrhythmias and kidney failure. In all patients with reported adverse heart and kidney reactions, anagrelide treatment was stopped.

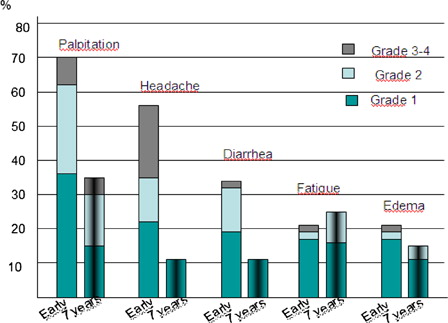

The median daily dose used of anagrelide at study end (7 years) was 1.5 mg (range 0.5–3.5). Complete response, defined as a platelet count <400 × 109/l or <600 × 109/l in symptomatic and asymptomatic patients, respectively, was observed in 81% of the patients still on anagrelide; however, four of these patients had combination therapy with other cytoreductive drugs. During the first years of the study, side effects were common and often resulted in withdrawal of anagrelide.Citation17 Seventeen out of the 26 patients who remained on angrelide at study end still experienced side effects; however, the frequency and severity of side effects was now less pronounced. The most common reported side effects were palpitations and fatigue (). Despite side effects, patients still on anagrelide at study end rated the feasibility of the treatment on a 10-grade scale as high with a mean value of 9.1 (data not shown).

Thrombosis, bleeding, and death

Nineteen of 59 evaluable patients experienced 18 thromboembolic events and six events of bleeding (), equivalent to an incidence rate of 3, 8 and 1, 3 per 100 patient-years, respectively. Venous thromboembolism was only seen in 2 cases, arterial in 16. The incidence rate of thrombosis and bleeding in the patients who had been treated only with anagrelide was similar, 3.7 and 1.4 events per 100 patient-years, respectively. None of the reported thromboses in this group of patients was venous. The most common type of arterial vascular event was stroke/transient ischemic attack, and two patients died from stroke. Among patients with bleeding complications three had a major hemorrhage (one intracranial and two gastrointestinal). All six events of bleeding were observed in patients with PV and all had ongoing treatment with ASA. None of the patients with a major bleeding were still treated with anagrelide when the bleeding occurred. In the ET group there were no hemorrhagic events in spite of aspirin treatment in 64% of the patients. The incidence of thromboembolic events was re-analyzed in relation to established diagnosis after the blinded bone marrow examination. There were seven and five events of thrombosis in patients with ‘true ET’ and PMF, respectively (data not shown). The numbers of thromboembolic events are too few to allow a statistical comparison between the two groups.

Table 3. Thrombotic and hemorrhagic events during study period in patients with an initial diagnosis of ET and PV

Discussion

The 2008, WHO criteria for diagnosis of ET and PMFCitation6 have given rise to controversy and intense discussion. The feasibility of the morphologic criteria for differentiating between ET and prefibrotic PMFCitation20 consistent with fiber grading 0 and 121 has gained support in a number of studies,Citation2,Citation22–Citation24 but has also been challengedCitation8,Citation9,Citation11 and the existence of the entity prefibrotic PMF has been questioned. Some prefer the view that there is a continuous development from ET to MF.Citation25 However, both sides in this discussion agree that the presence of bone marrow fibrosis at diagnosis indicates a worse prognosis.Citation3,Citation5 The paper from the UK-PT1 group indicated that transformation to clinically overt MF was more common and the incidence of thrombosis higher in patients with fibrosisCitation5 even though these authors prefer to define these patients as ‘ET with fibrosis’.

In the present study, a higher than expected incidence of overt MF among the patients with the initial diagnosis of ET was noted at the 7-year follow-up. Therefore, a re-evaluation of the bone marrow morphology was initiated in all samples available from study start, and as many follow-up bone marrow biopsies as possible were obtained. The new bone marrow examination was performed blindly by two pathologists with extensive experience of the WHO classification criteria, who only had access to age and sex of the patients. As many as 17 of the 40 patients with an initial ET diagnosis (with available biopsy material) were re-evaluated as PMF and 2 as MPN-U. In the ‘true ET’ group no patient died from MPN-related causes, 19/21 were alive, and there was no patient with transformation to MF, MDS, or acute leukemia. Furthermore, in the 12 available follow-up bone marrow biopsies there was none with fibrosis.

In contrast, the PMF group showed two transformations to MDS during the study period, progression of MF (at least 1 grade) in 10 early prefibrotic PMF and there were seven cases of advanced (classical) WHO compatible PMF, a statistically significant difference even in this limited material. Four patients were dead, at least three of them from disease-related causes.

The study is small, but nevertheless our results support the importance of a strict adherence to the new WHO classification criteria in order to discriminate ET from early prefibrotic myelofibrosis since the prognosis appears to differ substantially. Our findings are in line with a recent large retrospective study on 1104 patients initially diagnosed as ET.Citation2 After a review of the bone marrow specimens according to the WHO morphological criteria it was found that patients with a revised diagnosis from ET to early prefibrotic PMF during a 15-year period had a significantly higher risk of developing overt myelofibrosis and leukemia compared to ET patients. The overall 15-year survival in this study was 80% in ET vs. 59% in early prefibrotic PMF.

In previous studies it has been reported that risk factors for transformation to overt myelofibrosis and leukemia include, e.g. anemia, increased serum lactate dehydrogenase, and extreme thrombocytosis.Citation2,Citation26–Citation28 However, it has also been suggested that such ‘risk factors’ instead are markers of early PMF.Citation2 In our study the hemoglobin level and leukocyte count were similar in patients with ‘true ET’ and in patients with PMF. There was a borderline statistical significant difference for a higher platelet count in PMF (P = 0.05) and a tendency for a higher serum lactate dehydrogenase, although not statistically significant. However, laboratory results might have been influenced by the fact that a substantial part of the patients at study start were not incident cases, and approximately 40% of patients in each group had been treated previously with other cytoreductive treatments.

Previous studies have found that anagrelide does not hinder progression of fibrosis in ETCitation5,Citation29 and the present study is in line with these results. In the PT-1 study it was concluded that the incidence of transformation to myelofibrosis was higher in the anagrelide group compared to the HU group.Citation12 Since our study was not designed to investigate whether anagrelide may enhance progression to MF, this question cannot be answered by the present study.

The complete response rate in patients still treated with anagrelide at study end was relatively high (81%, although four patients had combination therapies). Similar efficacy of anagrelide is reported from previous long-term follow-up studies.Citation15,Citation16 In concert with another study,Citation15 we found that withdrawal from anagrelide during the initial months of treatment was common due to a high rate of side effects . However, after 2 years few patients stopped treatment for this reason and patients still treated with anagrelide at study end reported high satisfaction with the drug.

The incidence rate of thrombosis in the present study was slightly higher than that has been reported in other studies with cytoreductive treatment. In a recent published study of 891 patients with WHO-defined ET, the incidence rate of thrombotic events was lower (1.9 per 100 patient-years). However, contrary to our study, half of the patients had low-risk ET.Citation30 In our study the occurrence of bleeding and thrombosis was similar in patients treated only with anagrelide and patients who had switched between therapies. Notably only two venous thromboses occurred, compared to 16 arterial events. From our study no venous thrombosis was observed in patients treated solely with anagrelide during the entire study.

Conclusion

From this prospective study we can conclude that a blinded re-evaluation of bone marrow trephines from study start and after at least 7 years of follow-up revealed that 2008 WHO criteria applied in a blinded setting were able to differentiate between true ET and PMF with a marked difference in follow-up outcome; patients re-diagnosed with PMF, 40% of the original ‘ET’ cohort, had a higher rate of deaths and transformations to overt myelofibrosis. A clinically observed incidence of this transformation in ET patients diagnosed by older criteria should call for a new bone marrow evaluation of the diagnostic bone marrow biopsy according to the WHO criteria. Our results are in line with previous findings that anagrelide treatment does not prevent fibrosis progression.

References

- Jaffe ES, Harris N, Stein H, Vardiman JW, editors. World Health Organization classification of Tumours of Hematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2001.

- Barbui T, Thiele J, Passamonti F, Rumi E, Boveri E, Ruggeri M, et al. Survival and disease progression in essential thrombocythemia are significantly influenced by accurate morphologic diagnosis: an international study. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:3179–84.

- Kvasnicka HM, Thiele J. The impact of clinicopathological studies on staging and survival in essential thrombocythemia, chronic idiopathic myelofibrosis, and polycythemia rubra vera. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2006;32:362–71.

- Thiele J, Kvasnicka HM. Chronic myeloproliferative disorders with thrombocythemia: a comparative study of two classification systems (PVSG, WHO) on 839 patients. Ann Hematol. 2003;82:148–52.

- Campbell PJ, Bareford D, Erber WN, Wilkins BS, Wright P, Buck G, et al. Reticulin accumulation in essential thrombocythemia: prognostic significance and relationship to therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2991–9.

- Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris N, Jaffe ES, Pileri SA, et al., editors. WHO classification of tumours of haematopoietic and lymhoid tissues. Lyon, France: IARC press; 2008.

- Thiele J, Kvasnicka HM, Mullauer L, Buxhofer-Ausch V, Gisslinger B, Gisslinger H. Essential thrombocythemia versus early primary myelofibrosis: a multicenter study to validate the WHO classification. Blood. 2011;117:5710–8.

- Brousseau M, Parot-Schinkel E, Moles MP, Boyer F, Hunault M, Rousselet MC. Practical application and clinical impact of the WHO histopathological criteria on bone marrow biopsy for the diagnosis of essential thrombocythemia versus prefibrotic primary myelofibrosis. Histopathology. 2010;56:758–67.

- Buhr T, Hebeda K, Kaloutsi V, Porwit A, Van der Walt J, Kreipe H. European Bone Marrow Working Group trial on reproducibility of World Health Organization criteria to discriminate essential thrombocythemia from prefibrotic primary myelofibrosis. Haematologica. 2012;97(3):360–5; Reply, Haematologica. 2012;97:e7–8.

- Thiele J, Orazi A, Kvasnicka HM, Franco V, Boveri E, Gianelli U, et al. European Bone Marrow Working Group trial on reproducibility of World Health Organization criteria to discriminate essential thrombocythemia from prefibrotic primary myelofibrosis. Haematologica. 2012;97(3):360–5; Comment, Haematologica. 2012;97:e5–6.

- Wilkins BS, Erber WN, Bareford D, Buck G, Wheatley K, East CL, et al. Bone marrow pathology in essential thrombocythemia: interobserver reliability and utility for identifying disease subtypes. Blood. 2008;111:60–70.

- Harrison CN, Campbell PJ, Buck G, Wheatley K, East CL, Bareford D, et al. Hydroxyurea compared with anagrelide in high-risk essential thrombocythemia. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:33–45.

- Petrides PE, Beykirch MK, Trapp OM. Anagrelide, a novel platelet lowering option in essential thrombocythaemia: treatment experience in 48 patients in Germany. Eur J Haematol. 1998;61:71–6.

- Steurer M, Gastl G, Jedrzejczak WW, Pytlik R, Lin W, Schlögl E, et al. Anagrelide for thrombocytosis in myeloproliferative disorders: a prospective study to assess efficacy and adverse event profile. Cancer. 2004;101:2239–46.

- Mazzucconi MG, Redi R, Bernasconi S, Bizzoni L, Dragoni F, Latagliata R, et al. A long-term study of young patients with essential thrombocythemia treated with anagrelide. Haematologica. 2004;89:1306–13.

- Storen EC, Tefferi A. Long-term use of anagrelide in young patients with essential thrombocythemia. Blood. 2001;97:863–6.

- Birgegard G, Bjorkholm M, Kutti J, Larfars G, Lofvenberg E, Markevarn B, et al. Adverse effects and benefits of two years of anagrelide treatment for thrombocythemia in chronic myeloproliferative disorders. Haematologica. 2004;89:520–7.

- Kutti J, Wadenvik H. Diagnostic and differential criteria of essential thrombocythemia and reactive thrombocytosis. Leuk Lymphoma. 1996;22 (Suppl. 1):41–5.

- Pearson TC, Messinezy M, Westwood N, Green AR, Bench AJ, Green AR, et al. A polycythemia vera updated: diagnosis, pathobiology, and treatment. Hematol Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2000;1:51–68.

- Thiele J, Kvasnicka HM. Diagnostic differentiation of essential thrombocythaemia from thrombocythaemias associated with chronic idiopathic myelofibrosis by discriminate analysis of bone marrow features–a clinicopathological study on 272 patients. Histol Histopathol. 2003;18:93–102.

- Thiele J, Kvasnicka HM, Facchetti F, Franco V, van der Walt J, Orazi A, et al. European consensus on grading bone marrow fibrosis and assessment of cellularity. Haematologica. 2005;90:1128–32.

- Florena AM, Tripodo C, Iannitto E, Iannitto E, Porcasi R, Ingrao S, et al. Value of bone marrow biopsy in the diagnosis of essential thrombocythemia. Haematologica. 2004;89:911–9.

- Gianelli U, Vener C, Raviele PR, Moro A, Savi F, Annaloro C, et al. Essential thrombocythemia or chronic idiopathic myelofibrosis? A single-center study based on hematopoietic bone marrow histology. Leuk Lymphoma. 2006;47:1774–81.

- Kreft A, Buche G, Ghalibafian M, Buhr T, Fischer T, Kirkpatrick CJ. The incidence of myelofibrosis in essential thrombocythaemia, polycythaemia vera and chronic idiopathic myelofibrosis: a retrospective evaluation of sequential bone marrow biopsies. Acta Haematol. 2005;113:137–43.

- Campbell PJ, Green AR. The myeloproliferative disorders. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2452–66.

- Alvarez-Larran A, Cervantes F, Bellosillo B, Giralt M, Julia A, Hernandez-Boluda JC, et al. Essential thrombocythemia in young individuals: frequency and risk factors for vascular events and evolution to myelofibrosis in 126 patients. Leukemia. 2007;21:1218–23.

- Gangat N, Wolanskyj AP, McClure RF, Li CY, Schwager S, Wu W, et al. Risk stratification for survival and leukemic transformation in essential thrombocythemia: a single institutional study of 605 patients. Leukemia. 2007;21:270–6.

- Passamonti F, Rumi E, Arcaini L, Boveri E, Elena C, Pietra D, et al. Prognostic factors for thrombosis, myelofibrosis, and leukemia in essential thrombocythemia: a study of 605 patients. Haematologica. 2008;93:1645–51.

- Hultdin M, Sundstrom G, Wahlin A, Lundstrom B, Samuelsson J, Birgegard G, et al. Progression of bone marrow fibrosis in patients with essential thrombocythemia and polycythemia vera during anagrelide treatment. Med Oncol. 2007;24:63–70.

- Carobbio A, Thiele J, Passamonti F, Rumi E, Ruggeri M, Rodeghiero F, et al. Risk factors for arterial and venous thrombosis in WHO-defined essential thrombocythemia: an international study of 891 patients. Blood. 2011;117:5857–9.