Abstract

We report a primary bone marrow diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in a 52-year-old post-menopausal woman that evaded definitive diagnosis initially due to deceptive clinical features, non-contributory radiological findings, and an extensive reactive lymphoid infiltrate masking the relatively few neoplastic B-cells on bone marrow biopsy. The correct diagnosis was apparent only after a repeat bone marrow procedure and review of the previous histology and immunohistochemistry. The case illustrates the pitfall of assuming mixed B- and T-cell infiltrates in the bone marrow to be invariably benign. A high index of suspicion regardless of the clinical and/or radiological absence of lymphadenopathy or organomegaly and critical examination of each individual cell population in immunohistochemically stained material are essential for correct identification of this rare entity.

Introduction

Primary bone marrow lymphomas are rare tumors that often pose a diagnostic challenge.Citation1 We report a primary large B-cell lymphoma of the bone marrow that created initial diagnostic uncertainty requiring a repeat bone marrow procedure.

Case report

A 52-year-old post-menopausal lady presented in November 2011 with anemia of 6-month duration requiring 3 units of packed red cell transfusions. She was unresponsive to prior hematinic therapy. There was no history of B-symptoms, bleeding, jaundice, edema, bone pains, or any perceived lump or mass. Dietary, drug, and gynecological histories were unrewarding. Clinical examination revealed pallor, but no lymph node enlargement or abdominal organomegaly. Clinical differential diagnoses entertained were myelodysplastic syndrome (refractory anemia), pure red cell aplasia, paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH), or an occult lymphoproliferative disorder or metastatic malignancy involving the bone marrow.

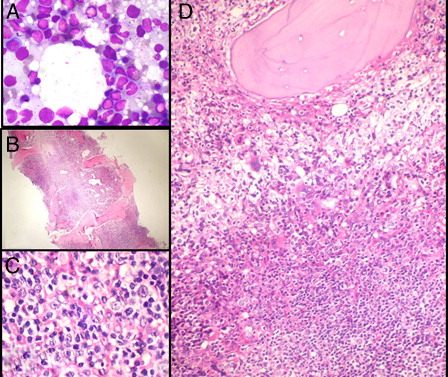

Investigations revealed hemoglobin 60 g/l, platelet count 286 × 109/l, corrected reticulocyte count 1.2%, and total leucocyte count 8.1 × 109/l with a normal differential count including 23% morphologically unremarkable lymphocytes. Bone marrow aspirate smears were particulate with adequate granulopoiesis, normal megakaryocytes, and megaloblastic erythropoiesis. Lymphocytes comprised 35% of all cells on the marrow aspirate and imprint smears. They were of normal size and morphology (A). No atypical cells or any increase in blasts were noted. Perl's stain revealed high-normal iron stores with no ring sideroblasts.

Figure 1. (A) Bone marrow imprint smears show a mild excess of small-sized lymphoid cells (MGG-Giemsa ×1000). (B) Hypercellular bone marrow biopsy shows large collections as well as an interstitial excess of lymphoid cells (H&E ×100). (C) Larger nucleolated neoplastic lymphoid cells are scattered amidst reactive lymphocytes (H&E ×1000). (D) A non-paratrabecular lymphoid aggregate comprised of predominantly small lymphoid cells. A few histiocytes and normal hemopoietic elements are also present (H&E ×200).

The trephine biopsy was hypercellular (B) with an interstitial excess as well as three to four predominantly non-paratrabecular collections of small-sized, mature-appearing lymphoid cells (D). Occasional cells were larger in size and nucleolated (C and 2, lower left). These were felt to be compatible with the megaloblasts on the aspirate. There was an increase in histiocytes; however, no eosinophilia, plasmacytosis, granulomas, or necrosis were present. A modified Gordon and Sweet's silver stain demonstrated a loose meshwork of reticulin fibers with many intersections (EUMNET grade MF-1, on a scale of 0–3). In view of the lymphoid aggregates, marrow involvement by non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) was suspected and immunohistochemistry (IHC) was ordered.

A preliminary report communicated the suspicion of NHL to the clinical care team, who initiated work-up to exclude impalpable lymphadenopathy. Her abdominal ultrasound and computed tomographic (CT) scans of the thorax and abdomen were negative for internal lymph node enlargement or any other significant pathology. A positron emission tomographic-CT scan also did not reveal any unexpected 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (18F-FDG) uptake. Investigations for thyroid, renal, and liver functions were essentially within normal limits. Serological tests for HIV, Hepatitis B and C, and the serum lactate dehydrogenase and uric acid levels were also normal.

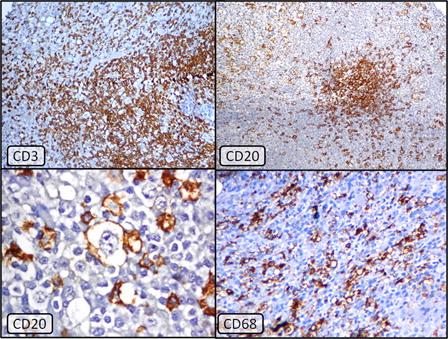

IHC on the bone marrow biopsy, in the meanwhile, revealed predominantly CD3-positive T-cell aggregates with smaller clusters (, top left) as well as scattered CD20 and CD79a positive B-cells (, top right). The T- and B-cells were present in roughly equal proportions. No significant cell population expressing CD15 or CD30 was present. In view of this mixed T- and B-cell pattern, together with the negative work-up for an extra-medullary primary lymphoma, the biopsy was finally signed out as being suspicious for lymphoma but with inconclusive IHC (i.e. a reactive lymphoid proliferation could not be definitively excluded). A close clinical and hematological follow-up with a repeat bone examination after excluding autoimmune and chronic infectious diseases was suggested.

Figure 2. Top left: CD3 immunostain showing numerous T-lymphocytes forming nodules as well as scattered interstitially (Immunoperoxidase × 40, hematoxylin counterstain). Top right: CD20 immunostain demonstrating positivity in collections as well as scattered larger lymphoma cells (Immunoperoxidase × 40, hematoxylin counterstain). Lower left: Membranous positivity of CD20 in the abnormal large lymphoma cells. These cells were best visualized under oil immersion (Immunoperoxidase ×1000, hematoxylin counterstain). Lower right: CD68 immunolabeling reveals marked increase in histiocytes in the background (Immuno-peroxidase ×1000, hematoxylin counterstain).

The patient continued to be transfusion dependent. Flow cytometry on peripheral blood granulocytes for PNH and tests for auto-immune disorders including an antinuclear antibody and antiglobulin test as well as work-up for celiac and inflammatory bowel disease were negative. Bone marrow examination was therefore repeated in January 2012. The second biopsy revealed even larger aggregates of small lymphoid cells, now with suppressed hematopoiesis. Scattered amidst these cells were many larger cells, with round to pleomorphic nuclei, prominent nucleoli, opened up chromatin, and moderate amount of cytoplasm. Diffuse pericellular reticulin fibrosis had increased from EUMNET-grade MF-1 previously to MF-2 in this biopsy. A specimen taken for flow cytometry was markedly hemodilute; however, immunophenotyping showed ∼30% lymphoid cells. Approximately 97% of these were CD3-positive with ∼11% expressing CD4 and ∼85% expressing CD8. These cells showed normal expression patterns of CD2, CD5, and CD7. CD19-positive B cells comprised 0.8% of acquired events and further analyses on this subset were not feasible.

IHC on the previous biopsy specimen was reviewed and the larger of the CD20- and CD79a-positive nucleolated cells were, in retrospect, interpreted as compatible with the minor population of scattered abnormal cells, less conspicuous on the hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections (, lower left). Further stain for CD68 revealed dense histiocytic infiltrates (, lower right). The histological differential diagnoses now were diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) (likely T-cell and histiocyte-rich large B-cell lymphoma [THRLBCL]) versus a nodular lymphocyte predominant Hodgkin lymphoma (NLPHL). Since no T-cell rosetting of the B-cells or ‘popcorn’ cells with deeply folded and convoluted nuclei were present, NLPHL was felt to be unlikely. The final diagnosis was therefore primary bone marrow large B-cell NHL with a marked T-cell and histiocytic response, compatible with THRLBCL.

Discussion

Lymphoid infiltrates in the marrow in a symptomatic middle-aged patient without a known primary lymphoproliferative disorder and sans lymphadenopathy or organomegaly on examination, imaging, and other staging procedures may be reactive, age-related, or may rarely indicate a primary bone marrow lymphoma. Reactive causes of lymphoid aggregates are numerous and include infections, inflammatory states, hemolysis, myeloproliferative neoplasms, autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, congenital immunodeficiency, angioimmunoblastic lymphadenopathy, following bone marrow transplantation and even thymomas.Citation2,Citation3

Confident exclusion of benign lymphoid collections before considering rare primary marrow lymphomas can be challenging on morphology alone.Citation2 Finding abnormal-appearing lymphoid cells, monoclonality on genetic studies, or immunological surrogates of monoclonality such as surface light chain restriction in B-cells, or aberrant expression/loss of antigens in T-cells favor malignancy.Citation1–Citation3 Conversely, the presence of mixed B- and T-cell infiltrates on immunophenotyping, whether by flow cytometry or IHC has been considered suggestive of a reactive process; however, with important caveats.Citation2–Citation4

Primary bone marrow lymphomas are rare neoplasms with only a few case reports and small series in the literature.Citation1,Citation5,Citation6 In possibly the largest study of 21 cases from 12 institutions across 7 countries,Citation1 DLBCL comprised 15 cases (71.4%), followed by follicular lymphoma and peripheral T-cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified, respectively. As in our case, 3 of these 15 DLBCL revealed extensive coexisting reactive lymphocytic infiltrates.Citation1

The reported incidence of bone marrow involvement in THRLBCL ranges widely from <1 to 67% with most larger series revealing higher incidences.Citation7–Citation9 Paratrabecular and diffuse patterns of infiltration are predominant, but nodular and interstitial infiltrates, as in our case, have also been described.Citation9 Skinnider et al.Citation9 found the pale eosinophilic low-power appearance of the infiltrates (due to their histiocyte-rich nature as well as relative hypocellularity compared to the surrounding marrow) to be a helpful diagnostic feature. A marrow reticulin stain can also highlight subtle nodules. Thiele et al.Citation2 reported that reticulin fibrosis was more likely to be moderate to advanced in malignant lymphoid infiltrates (except in cases of chronic lymphocytic leukemia) and borderline to minimal in benign ones (with the exception of HIV myelopathy).

Despite the above clues, in our patient, the initial diagnostic problem was one of how much importance to ascribe to the few scattered large lymphoid cells in an otherwise predominantly small cell infiltrate that was mixed CD3 and CD20 positive (although extensive). The diagnostic delay necessitating a second bone marrow examination and probably unnecessary work-up were, in retrospect, felt to be due to over-importance accorded to this mixed B- and T-cell population compounded by the unusual presentation of the patient (refractory anemia without any lymphadenopathy or organomegaly leading to a low clinical index of suspicion for NHL) and the unrewarding biochemical and radiological work-up. More than one experienced hematopathologist reviewing the initial bone marrow felt that to label the patient as NHL based only on 20–30 CD20-positive large cells might result in an overcall with problems of reproducibility of the diagnosis. The subsequent availability of another bone marrow specimen, with nearly identical findings, and a careful review of the IHC establishing that most of the CD20-positive cells were large in size and abnormal in morphology led to the correct conclusion.

Although IHC was the clinching investigation in our case, the experience of other groups has varied. While Thiele et al.Citation2 and Bluth et al.Citation3 found immunostaining (CD20 and CD45RO) to be a useful adjunct to morphology in the evaluation of marrow lymphoid aggregates, another group concluded that reactive and neoplastic lymphomatous infiltrates generally could not be differentiated on the basis of immunohistological findings alone.Citation4 In the latter study, in both reactive follicles and in neoplastic (lymphomatous) infiltrates, T-cells regularly occurred in higher numbers than B cells, and focally assembled lymphoid cells were mainly B lymphocytes with many intermingled T cells.

The problem of minor neoplastic cell populations in a reactive polymorphous background may also be encountered in Hodgkin lymphoma.Citation10 In our case, CD20-expressing neoplastic cells negative for CD15 and CD30 excluded classical Hodgkin lymphoma. NLPHL remains a possibility. However, it only rarely involves the marrow (<1% cases) as opposed to 43–62% cases of THRLBCL.Citation8–Citation10 A primary diagnosis of NLPHL is therefore recommended not to be made on bone marrow biopsy.Citation11 In addition, if a patient with a tissue diagnosis of NLPHL shows marrow involvement, it has been suggested that the primary diagnosis should be reviewed and THRLBCL considered.Citation11 Biological similarities exist between NLPHL and THRLBCLCitation12 and cases of one transforming to the other have been described.Citation13 It has been postulated that the natural history of these overlapping disorders may involve progressive transformation of germinal centers to NLPHL and onwards to THRLBCL.Citation13

Conclusion

Our case of a primary bone marrow lymphoma highlights the diagnostic challenges posed by these rare neoplasms. It illustrates the pitfall of assuming mixed B- and T-cell infiltrates in the bone marrow to be invariably benign and the importance of critically examining each individual cell population in immunohistochemically stained material. Awareness of subtle patterns of marrow involvement and a high index of suspicion for these neoplasms, clinical/radiological data notwithstanding, on the part of the reporting hematopathologist may help avoid diagnostic delay in such cases.

References

- Martinez A, Ponzoni M, Agostinelli C, Hebeda KM, Matutes E, Peccatori J, et al. Primary bone marrow lymphoma: an uncommon extranodal presentation of aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36:296–304.

- Thiele J, Zirbes TK, Kvasnicka HM, Fischer R. Focal lymphoid aggregates (nodules) in bone marrow biopsies: differentiation between benign hyperplasia and malignant lymphoma – a practical guideline. J Clin Pathol. 1999;52:294–300.

- Bluth RF, Casey TT, McCurley TL. Differentiation of reactive from neoplastic small-cell lymphoid aggregates in paraffin-embedded marrow particle preparations using L-26 (CD20) and UCHL-1 (CD45RO) monoclonal antibodies. Am J Clin Pathol. 1993;l99:150–6.

- Horny HP, Engst U, Walz RS, Kaiserling E. In situ immunophenotyping of lymphocytes in human bone marrow: an immunohistochemical study. Br J Haematol. 1989;71:313–21.

- Strauchen JA. Primary bone marrow B-cell lymphoma: report of four cases. Mt Sinai J Med. 2003;70:133–8.

- Chang H, Hung YS, Lin TL, Wang PN, Kuo MC, Tang TC, et al. Primary bone marrow diffuse large B cell lymphoma: a case series and review. Ann Hematol. 2011;90:791–6.

- Krishnan J, Wallberg K, Frizzera G. T-cell-rich large B-cell lymphoma. A study of 30 cases, supporting its histologic heterogeneity and lack of clinical distinctiveness. Am J Surg Pathol. 1994;18:455–65.

- Achten R, Verhoef G, Vanuytsel L, De Wolf-Peeters C. T-cell/histiocyte-rich large B-cell lymphoma: a distinct clinicopathologic entity. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:1269–77.

- Skinnider BF, Connors JM, Gascoyne RD. Bone marrow involvement in T-cell-rich B-cell lymphoma. Am J Clin Pathol. 1997;108:570–8.

- Munker R, Harenclever D, Brosteanu O, Hiller E, Diehl V. Bone marrow involvement in Hodgkin's disease: an analysis of 135 consecutive cases. German Hodgkin's lymphoma study group. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:682–3.

- Herrick J, Dogan A. Lymphoma. In: , Erber WN, (ed.). Diagnostic techniques in hematological malignancies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2010. p. 206–43.

- Pittaluga S, Jaffe ES. T-cell/histiocyte-rich large B-cell lymphoma. Haematologica. 2010;95:352–6.

- Zhao FX. Nodular lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin lymphoma or T-cell/histiocyte rich large B-cell lymphoma: the problem in “grey zone” lymphomas. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2008;1:300–5.