Abstract

Imatinib has been considered as the gold standard for drug therapy of chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) because it offers higher cytogenetic response and better quality of life than traditional drugs. In this study we applied the standard 400 mg dose of imatinib in 37 CML Ph (+) Mexican patients, monitoring their cytogenetic response using fluorescent in situ hybridization and carrying out molecular analyses using reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction. The study included 19 male and 18 female patients with a median age of 41 years. The median follow-up time from diagnosis was 56 months. Thirty-six patients (97%) achieved complete hematologic response in a median time of 29 days. Complete cytogenetic response and complete molecular remission was observed in only five (13%) and three (8.1%) patients, respectively, less than the expected rate (50–90%) reported in other studies.

Introduction

Chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) is a clonal disease of the hematopoietic stem cell characterized by a cytogenetic abnormality called the Philadelphia (Ph) chromosome. This abnormality is generated by a reciprocal translocation between chromosomes 9 and 22.Citation1 The resulting BCR/ABL fusion encodes a protein with aberrant ABL tyrosine kinase activity, which has a key role in the pathogenesis of CML.Citation2,Citation3 BCR/ABL mediates the development and maintenance of CML through interaction with multiple downstream signaling partners resulting in altered cellular adhesion, activation of mitogenic signaling and inhibition of apoptosis, leading to the transformation of the hematopoietic stem cells.Citation4 During the 1990s, interferon (INF) alpha was the preferred treatment for patients with CML,Citation1–Citation5 achieving survival benefits for a minority of patientsCitation5–Citation8 but associated with an adverse impact on quality of life.Citation9 The introduction of imatinib mesylate in the late 1990s transformed the treatment of patients with CML,Citation10–Citation13 offering a superior cytogenetic response with better quality of life as compared with INF-alpha treatment.Citation14 Imatinib mesylate (Glivec, Novartis, Mexico) is a potent and selective tyrosine kinase inhibitor that blocks the proliferation of Ph-positive progenitors in all phases of CML, although responses are most durable in patients who are in chronic phase.Citation15 The activity of imatinib has made it the current frontline therapy in CML patients as it induces complete cytogenetic response (CCR) in 50–90% of chronic phase CML patients.Citation10,Citation16 Using imatinib in newly diagnosed chronic phase CML patients at a dosage of 400 mg/day, has shown an estimated CCR of 87% at some point within 5 years of follow-up, and an estimated major molecular response (MMR) of 37% at 12 months.Citation17 Despite the high initial response rates, approximately 10–15% of chronic phase CML will display primary or acquired cytogenetic resistance to imatinib.Citation17,Citation18 Rising BCR/ABL transcript levels could indicate loss of response, often as a consequence of developing BCR/ABL mutations.Citation19 Many mechanisms of resistance have been described, including mutations in ABL kinase domain, BCR/ABL genomic amplification and variations in plasma imatinib levels.Citation18,Citation20,Citation21 Molecular responses have prognostic significance in CML patients.Citation22 Patients who achieve early molecular responses are more likely to attain durable cytogenetic responses and less likely to experience disease progression.Citation4,Citation23 Cytogenetic assessment is the most widely used method for disease monitoring in CML patients.Citation4 Fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) is not a standardize method but can be used instead of conventional cytogenetic assessment; however, when using this method it is possible that some chromosome aberrations that may have an impact on the prognosis, besides the Philadelphia chromosome, may not be detected.Citation24,Citation25 Molecular assessment using real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) represents the most sensitive method available for monitoring disease status and residual disease.Citation22,Citation26 In this study, we included 37 CML patients who had started treatment with the standard 400 mg dose of imatinib, and we assessed their cytogenetic response using FISH and persistence of residual disease using RT-PCR in a point of their treatment.

Materials and methods

Patients diagnosed with CML between 1998 and 2008 at the Hospital Universitario ‘Dr. José Eleuterio González’ in Monterrey, Mexico, were included in this clinical trial. Eligibility criteria were adults with diagnosis of CML Ph (+) on an imatinib regimen for at least the previous 6 months. Patients who were intolerant or inconstant to imatinib were excluded. All subjects provided voluntary written informed consent before any trial procedure was performed according to institutional guidelines. Samples of peripheral blood for complete blood count and molecular analysis were obtained at one point of the imatinib treatment. FISH analyses done throughout imatinib treatment before the patients were included in the study, were analyzed retrospectively. We use FISH to monitor disease because of its low cost. All samples were processed at the Hematology Department of the Hospital Universitario.

Cytogenetic assessment

FISH done on peripheral blood cells was used for cytogenetic assessment. It was performed on nucleated cells using differently labeled BCR and ABL probes. Two-hundred cells in interphase were scored for each sample. Cells were considered normal when two red signals (ABL gene) and two green signals (BCR gene) were displayed. The FISH pattern of Ph-positive cells consisted of one red, one green, and two yellow signals. The cut-off limit for BCR/ABL-positive analysis was 0.5%.

Molecular analysis

Molecular analysis was done using peripheral blood cells. BCR/ABL transcript levels were determined by real-time reverse transcription PCR (RT-PCR). A 20-ml peripheral blood sample was collected using an EDTA tube. Mononuclear cells were obtained by Ficoll-Hypaque density centrifugation with Histopaque®-1077 (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, USA). Total RNA was isolated by a column-based system using RNeasy (QIAGEN, USA) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. After isolation, the RNA quality and concentration were determined by measuring the optical density at 260 nm using spectrophotometry. cDNA was obtained by RT-PCR using SuperScript™ II (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), and used as a template in a multiplex RT-PCR reaction, employing three specific primers for BCR-ABL: c4a2(1082pb), c3a2(947pb), c4a3(908pb), c3a3(773pb), b3a2(407pb), b2a2(333pb), e1a2(281pb), b3a3(233pb), b2a3(159pb) and e1a3(107pb) (F-BCR-M-m5′TGCAGTCATGAAAGAGATCAAA3′,FBCRμ5′TCCCGTAGGTCATGAATTCAA3′,RABL5′AGGAGGTTCCCGTAGGTCAT3′), and 2 primers (FGAPDH5′AGTCAGCCGCATCTTCCGTCGCCTA,RGAPDH5′GAGTGCTTCCACGATAGCTGACATGGAT) for GAPDH (Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase) control.

Response definition

Complete hematological response was defined as a WBC count < 10 × 109/l, a platelet count < 450 × 109/l, no immature cells in peripheral blood, and disappearance of all signs and symptoms of leukemia. Cytogenetic response was defined as complete (0% Ph-positive cells), partial (1–34% Ph-positive cells), and minor (35–90% Ph-positive cells). Molecular response was defined as complete response when BCR/ABL transcript was not detectable, and major response when a <0.1 ratio for BCR/ABL was detectable.

Results

Thirty-seven Ph (+) CML Mexican patients, 19 male and 18 female, made up the sample group. Median age for the group was 41 years (range 16–73 years). Median follow-up from diagnosis was 56 months (range 9–131), and median follow-up from the start of imatinib was 40 months (range 8–80). Imatinib was administered to all patients, 20 of whom (54.1%) started their treatment with Hydroxyurea as they were diagnosed before imatinib was available or were unable to obtain imatinib given financial limitations. The median time between diagnosis and imatinib start up was 2 months. No one received interferon or cytarabine. The initial daily dose of imatinib used was 400 mg, but ranged from 300 to 600 mg according to hematological tolerance. Five patients (13.5%) needed dose reduction to 300 mg as they exhibited hematological toxicity. The initial imatinib dose was reestablished as soon as the patient presented hematological recovery. Additional hematological side effects (rash and edema) were observed in less than 5% of the patients. These effects had no clinical significance. Thirty-six patients were in chronic phase and one patient in blastic phase when started on imatinib treatment. When patients entered the study, 10 had been receiving imatinib for between 6 and 11 months, 10 had been receiving imatinib for between 12 and 24 months, and 17 had been receiving imatinib for more than 24 months (median 36, range 29–60 months). Thirty-six patients (97%) achieved complete hematologic response, within a median time of 29 (12–168) days. Cytogenetic responses for all patients at 12 and 18 months after starting imatinib are shown in . At last follow-up, some kind of cytogenetic response was demonstrated in all patients; CCR was observed in five patients (13.5%), three of them received imatinib during 28, 38, and 54 months, and two patients had received it during 80 months. Partial cytogenetic response was observed in 28 patients (75.7%) with a median imatinib treatment time of 44 (13–80) months. Minor cytogenetic response was observed in four patients (10.8%), who had received imatinib during 8, 18, 24, and 25 months, respectively. Complete molecular response was observed in only three patients (8%) who received imatinib 500 mg daily during 36, 48, and 60 months, respectively. MMR was not observed. Mutation T315I was negative in all 37 patients.

Table 1. Cytogenetic responses at 12 and 18 months after initiation of imatinib and last follow-up for all patients

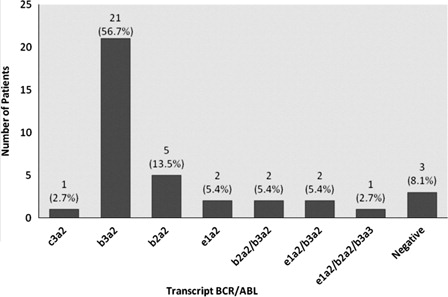

Overall survival (OS) at 5 years was 80.2%, with an OS mean of 72.5 months (SE 3.25, IC95%: 66.15–78.89). The 37 samples were analyzed for BCR-ABL transcripts in a Multiplex PCR detecting the rearrangement of oncoproteins p230BCR-ABL, p210BCR-ABL, and p190BCR-ABL. The most common transcript was (b3a2) p210BCR-ABLin 21 patients (56.76%). Five patients (13.5%) had the transcript (b2a2) p210BCR-ABL while three patients were negative for BCR-ABL transcripts because complete molecular response ().

Figure 1. Frequency of BCR/ABL transcripts. Three patients were negative for BCR-ABL transcripts because complete molecular response.

The patients were divided into two groups, those in which transcript (b3a2) p210BCR-ABL was demonstrated (group 1) and those with any other BCR-ABL transcript or negative result (group 2). Demographic characteristics for both groups are shown in . At diagnosis, patients in Group 1 showed a significantly lower hemoglobin (Hb) mean (9.1 ± 1.8 g/dl) than patients in Group 2 (11.4 ± 2 g/dl) with a significant difference of P = 0.006. Although other aspects of the WBC count were worse in patients of Group 1 compared with those in Group 2 (189.9 K/μl vs. 149.1 K/μl and neutrophils 158.2 K/μl vs. 86.9 K/μl), there was no statistically significant difference between groups (P values: 0.601 and 0.335, respectively). Moreover, there was no difference in the mean number of platelets between the two groups (437 K/μl vs. 550.9 K/μl, P = 0.455).

Table 2. Demographic characteristics of b3a2 transcript group and other transcript group

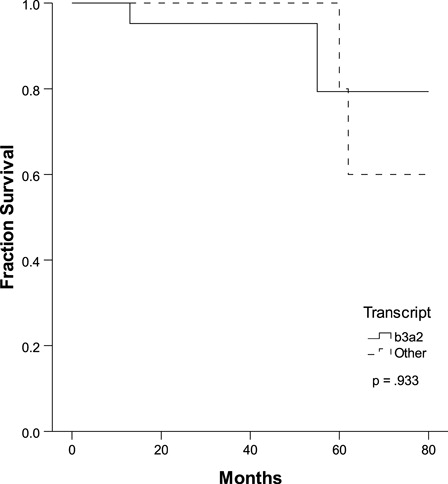

There was no significant difference in the cytogenetic responses of the two groups at the 12- and 18-month points between the initiation of imatinib and the last follow-up (). We found a 5-year OS of 80% with a mean of 72 months in both groups (P = 0.933, ); however, the OS at 80 months was different between groups: 79.4% (group 1) vs. 60% (group 2), without achieving any statistical significance.

Table 3. Cytogenetic responses at 12 and 18 months and last follow-up for both groups

Discussion

Imatinib remains the gold standard for drug therapy of CML because it has proven to be active at all stages of CML, although responses are most substantial in patients who are in chronic phase.Citation15 Failure to respond to imatinib may be due to several mechanisms, most frequently the presence of imatinib-resistant mutations in the Bcr-Abl gene. In this study, we analyzed the hematological, cytogenetic, and molecular effects of imatinib in 37 CML patients. We did not observe important hematological side effects, and tolerability to imatinib was good; however, some patients exhibited hematological toxicity and their daily drug dose had to be modified. Although these adverse events disappeared and the patients were able to continue their treatment, such events could impact the cytogenetic response. A complete hematologic and clinical remission was achieved in 36 patients (97%) similar to other studies,Citation10,Citation11,Citation16,Citation17 improving the quality of life of these patients. Many studies have reported complete cytogenetic remission in 50–90% of chronic phase CML patients who received daily 400 mg of imatinib; however, most of these studies included patients with a follow-up treatment of more than 5 years with imatinib.Citation16,Citation17,Citation27,Citation28 In our study, complete cytogenetic and complete molecular remission was achieved in only 5 (13.5%) and 3 (8%) patients, respectively, less than the expected rate (50–90%) reported in other studies.Citation17,Citation28 However, it must be pointed out that partial cytogenetic response was observed in 28 patients (75.7%). The lower than expected cytogenetic and molecular response could be explained by the short follow-up period for the patients or the difficulty of increasing the dose of imatinib because of side effects. Cortes et al.Citation23 showed complete molecular remission in 34% of CML patients treated with imatinib at a daily dose of 400–800 mg; they found that treatment with high-dose imatinib was the only variable independently associated with an increased probability of achieving major molecular remission. The principal obstacle to increasing the imatinib dose in our study was hematologic toxicity.

BCR/ABL b3a2 and b2a2 are the most frequent transcripts found in CML patients.Citation29–Citation31 In our study the incidence of b3a2 was 56.7%, similar to 54.2% found in other study in Mexican Mestizo patients done by Ruiz-Argüelles,Citation32 and the incidence of b2a2 was 13.3%. Some studies have shown that b2a2 may be more sensitive to imatinib,Citation33 whereas b3a2 can implicate an inferior prognosis.Citation34 In our series, patients with b3a2 transcript showed worse hematological parameters at diagnosis than those with any other transcripts, exhibiting a significant difference in the Hb value between both groups (9.1 vs. 11.4 g/dl, P = 0.006). This result is in contrast with those of other studies that found no difference in Hb or total leukocyte count.Citation29,Citation33–Citation35 Platelet count has been described as higher in patients with b3a2 transcript than those with b2a229; however, in our study, patients with the b3a2 transcript had a lower platelet count than those with any other transcript. Sharma et al.Citation34 found significant differences in cytogenetic response between patients with b2a2 and b3a2 transcripts (59% vs. 28%, P = 0.040).

In our study, despite the initial blood cell count at diagnosis, there was no difference in OS and cytogenetic responses between transcript groups, similar to the results of other studies.Citation33–Citation35 Despite these data, the prognostic value of these transcripts deserves further investigation.

In summary, patients included in this study experienced good hematologic remission although both complete cytogenetic and molecular remission incidences were lower than expected. Imatinib as a first-line therapy for CML has proven highly effective in hematologic and clinical responses, improving the prognosis and the quality of life of many patients. The second generation Bcr-Abl tyrosine kinase inhibitors (dasatinib and nilotinib) have demonstrated high response rates in patients who failed to respond to imatinib and could be used as first-line therapy for CML patients in an attempt to achieve higher cytogenetic and molecular response rates.

Another therapeutic option able to induce durable remission in CML patients is allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (SCT). Four years ago we conducted a study comparing CML treatment with a tyrosine kinase inhibitor and one with allogeneic SCT, which concluded that SCT was preferable given its low cost and similar overall survival rates.Citation36 Longer follow-up periods should determine the effectiveness of imatinib in this group of patients and further studies comparing complete molecular remission in patients who received a second generation Bcr-Abl tyrosine kinase inhibitors versus an allogeneic SCT should be done.

References

- Sawyers CL. Chronic myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(17):1330–40.

- Lugo TG, Pendergast AM, Muller AJ, Witte ON. Tyrosine kinase activity and transformation potency of bcr-abl oncogene products. Science. 1990;247(4946):1079–82.

- Daley GQ, Van Etten RA, Baltimore D. Induction of chronic myelogenous leukemia in mice by the P210bcr/abl gene of the Philadelphia chromosome. Science. 1990;247(4944):824–30.

- Jabbour E, Cortes JE, Kantarjian HM. Molecular monitoring in chronic myeloid leukemia: response to tyrosine kinase inhibitors and prognostic implications. Cancer. 2008;112(10):2112–8.

- Chronic Myeloid Leukemia Trialists’ Collaborative Group. Interferon alfa versus chemotherapy for chronic myeloid leukemia: a meta-analysis of seven randomized trials. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1997;89(21):1616–20

- Kantarjian HM, Smith TL, O'Brien S, Beran M, Pierce S, Talpaz M. Prolonged survival in chronic myelogenous leukemia after cytogenetic response to interferon-alpha therapy. The Leukemia Service. Ann Intern Med. 1995;122(4):254–61.

- The Italian Cooperative Study Group on Chronic Myeloid Leukemia. Long-term follow-up of the Italian trial of interferon-alpha versus conventional chemotherapy in chronic myeloid leukemia. Blood. 1998;92(5):1541–8.

- Faderl S, Talpaz M, Estrov Z, Kantarjian HM. Chronic myelogenous leukemia: biology and therapy. Ann Intern Med. 1999;131(3):207–19.

- Homewood J, Watson M, Richards SM, Halsey J, Shepherd PC. Treatment of CML using IFN-alpha: impact on quality of life. Hematol J. 2003;4(4):253–62.

- Druker BJ, Talpaz M, Resta DJ, Peng B, Buchdunger E, Ford JM, et al. Efficacy and safety of a specific inhibitor of the BCR-ABL tyrosine kinase in chronic myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(14):1031–7.

- Kantarjian H, Sawyers C, Hochhaus A, Guilhot F, Schiffer C, Gambacorti-Passerini C, et al. Hematologic and cytogenetic responses to imatinib mesylate in chronic myelogenous leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(9):645–52.

- Peggs K, Mackinnon S. Imatinib mesylate–the new gold standard for treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(11):1048–50.

- Alimena G, Breccia M, Luciano L, Quarantelli F, Diverio D, Izzo B, et al. Imatinib mesylate therapy in chronic myeloid leukemia patients in stable complete cytogenic response after interferon-alpha results in a very high complete molecular response rate. Leuk Res. 2008;32(2):255–61.

- Hahn EA, Glendenning GA, Sorensen MV, Hudgens SA, Druker BJ, Guilhot F, et al. Quality of life in patients with newly diagnosed chronic phase chronic myeloid leukemia on imatinib versus interferon alfa plus low-dose cytarabine: results from the IRIS Study. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(11):2138–46.

- Hughes TP, Kaeda J, Branford S, Rudzki Z, Hochhaus A, Hensley ML, et al. Frequency of major molecular responses to imatinib or interferon alfa plus cytarabine in newly diagnosed chronic myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(15):1423–32.

- Kantarjian HM, Cortes JE, O'Brien S, Luthra R, Giles F, Verstovsek S, et al. Long-term survival benefit and improved complete cytogenetic and molecular response rates with imatinib mesylate in Philadelphia chromosome-positive chronic-phase chronic myeloid leukemia after failure of interferon-alpha. Blood. 2004;104(7):1979–88.

- Druker BJ, Guilhot F, O'Brien SG, Gathmann I, Kantarjian H, Gattermann N, et al. Five-year follow-up of patients receiving imatinib for chronic myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(23):2408–17.

- Hochhaus A, La Rosee P. Imatinib therapy in chronic myelogenous leukemia: strategies to avoid and overcome resistance. Leukemia. 2004;18(8):1321–31.

- Shah NP, Sawyers CL. Mechanisms of resistance to STI571 in Philadelphia chromosome-associated leukemias. Oncogene. 2003;22(47):7389–95.

- Peng B, Hayes M, Resta D, Racine-Poon A, Druker BJ, Talpaz M, et al. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of imatinib in a phase I trial with chronic myeloid leukemia patients. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(5):935–42.

- Picard S, Titier K, Etienne G, Teilhet E, Ducint D, Bernard MA, et al. Trough imatinib plasma levels are associated with both cytogenetic and molecular responses to standard-dose imatinib in chronic myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2007;109(8):3496–9.

- Baccarani M, Saglio G, Goldman J, Hochhaus A, Simonsson B, Appelbaum F, et al. Evolving concepts in the management of chronic myeloid leukemia: recommendations from an expert panel on behalf of the European LeukemiaNet. Blood. 2006;108(6):1809–20.

- Cortes J, Talpaz M, O'Brien S, Jones D, Luthra R, Shan J, et al. Molecular responses in patients with chronic myelogenous leukemia in chronic phase treated with imatinib mesylate. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11(9):3425–32.

- Lesser ML, Dewald GW, Sison CP, Silver RT. Correlation of three methods of measuring cytogenetic response in chronic myelocytic leukemia. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2002;137(2):79–84.

- Schoch C, Schnittger S, Bursch S, Gerstner D, Hochhaus A, Berger U, et al. Comparison of chromosome banding analysis, interphase- and hypermetaphase-FISH, qualitative and quantitative PCR for diagnosis and for follow-up in chronic myeloid leukemia: a study on 350 cases. Leukemia. 2002;16(1):53–9.

- Hughes T, Deininger M, Hochhaus A, Branford S, Radich J, Kaeda J, et al. Monitoring CML patients responding to treatment with tyrosine kinase inhibitors: review and recommendations for harmonizing current methodology for detecting BCR-ABL transcripts and kinase domain mutations and for expressing results. Blood. 2006;108(1):28–37.

- Kantarjian HM, Cortes JE, O'Brien S, Giles F, Garcia-Manero G, Faderl S, et al. Imatinib mesylate therapy in newly diagnosed patients with Philadelphia chromosome-positive chronic myelogenous leukemia: high incidence of early complete and major cytogenetic responses. Blood. 2003;101(1):97–100.

- O'Brien SG, Guilhot F, Larson RA, Gathmann I, Baccarani M, Cervantes F, et al. Imatinib compared with interferon and low-dose cytarabine for newly diagnosed chronic-phase chronic myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(11):994–1004.

- Adler R, Viehmann S, Kuhlisch E, Martiniak Y, Rottgers S, Harbott J, et al. Correlation of BCR/ABL transcript variants with patients' characteristics in childhood chronic myeloid leukaemia. Eur J Haematol. 2009;82(2):112–8.

- Rosas-Cabral A, Martinez-Mancilla M, Ayala-Sanchez M, Vela-Ojeda J, Bahena-Resendiz P, Vadillo-Buenfil M, et al. Analisis del tipo de transcripto bcr-abl y su relación con la cuenta plaquetaria en pacientes mexicanos con leucemia mieloide crónica. Gac Med Mex. 2003;139(6):553–9.

- Yaghmaie M, Ghaffari SH, Ghavamzadeh A, Alimoghaddam K, Jahani M, Mousavi SA, et al. Frequency of BCR-ABL fusion transcripts in Iranian patients with chronic myeloid leukemia. Arch Iran Med. 2008;11(3):247–51.

- Ruiz-Argüelles GJ, Garces-Eisele J, Reyes-Núnez V, Ruiz-Delgado G. Frequencies of the breackpoint cluster region types of the BCR/ABL fusion gene in Mexican Mestizo patients ith chronic myelogenous leukemia. Rev Invest Clin Mex. 2004;56(5):605–8.

- de Lemos JA, de Oliveira CM, Scerni AC, Bentes AQ, Beltrao AC, Bentes IR, et al. Differential molecular response of the transcripts B2A2 and B3A2 to imatinib mesylate in chronic myeloid leukemia. Genet Mol Res. 2005;4(4):803–11.

- Sharma P, Kumar L, Mohanty S, Kochupillai V. Response to Imatinib mesylate in chronic myeloid leukemia patients with variant BCR-ABL fusion transcripts. Ann Hematol. 2010;89(3):241–7.

- Polampalli S, Choughule A, Negi N, Shinde S, Baisane C, Amre P, et al. Analysis and comparison of clinicohematological parameters and molecular and cytogenetic response of two Bcr/Abl fusion transcripts. Genet Mol Res. 2008;7(4):1138–49.

- Ruiz-Arguelles GJ, Tarin-Arzaga LC, Gonzalez-Carrillo ML, Gutierrez-Riveroll KI, Rangel-Malo R, Gutierrez-Aguirre CH, et al. Therapeutic choices in patients with Ph-positive CML living in Mexico in the tyrosine kinase inhibitor era: SCT or TKIs? Bone Marrow Transplant. 2008;42(1):23–8.