Abstract

Novelty and Impact

This first study compares the survival of HCV-positive DLBCL treated with and without rituximab which showed in toxicity and the outcome.

Background

The effect of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection on prognosis and hepatic toxicity in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) in the rituximab era is unclear. The treatment and the outcome of patients with DLBCL and HCV infection are still a matter of debate.

Methods

We analyzed 137 DLBCL patients positive to HCV, treated with chemotherapy regimens include cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (CHOP) ± rituximab. Survival outcomes and hepatic toxicity were compared in DLBCL patients positive to HCV infection according to CHOP ± rituximab.

Result

Our result showed that the group of patients treated with R-CHOP has significant high incidence of hepatic toxicity grade (3–4) (28 vs. 18%, P value 0.001) and worse progression-free survival (55 vs. 80%, P value 0.002) in comparison with the group treated with CHOP, and also there is significant difference between both groups in overall survival. This first study compares the survival of HCV-positive DLBCL treated with and without rituximab which showed significant differences.

Conclusion

We conclude that HCV-positive patients with DLBCL treated with rituximab plus CHOP have high incidence in hepatic toxicity. Specific protocols evaluating antiviral therapy should be designed for these patients

Introduction

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is endemic in some countries such as Italy and Egypt. The role of HCV infection in lymphogenesis may be related to chronic antigenic stimulation of HCV.Citation1,Citation2 The causal role of HCV in lymphogenesis is also supported by the regression of indolent non-Hodgkin's lymphomas (NHLs) after eradication of the infection.Citation3,Citation4 Recent retrospective studies confirmed a high HCV seroprevalence among patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL).

Thus, studies comparing DLBCL outcomes based on HCV infection are extremely rare, and the prognostic value of HCV infection remain controversial, because of heterogeneity in the histology and the treatment strategies.Citation5,Citation6 Several series have shown good tolerance to standard chemotherapy for lymphoma patients who are infected with HCV.Citation5–Citation7 However, these studies were conducted in the pre-rituximab era.

Although the cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (CHOP) regimen have been the mainstay treatment for aggressive lymphomas for several decades, treatment outcomes have improved significantly since the introduction of rituximab in both young and elderly patients.Citation8–Citation12 Treatment and outcome of patients with DLBCL and HCV infection are still a matter of debate. In particular, the liver toxicity of aggressive and/or intensive chemotherapies in patients with HCV infection is not well known in the rituximab era.

In this report, we have analyzed the treatment-related toxicity, and the outcome of DLBCL lymphoma patients positive to HCV infection in the rituximab era in comparison with standard chemotherapy.

Patients and methods

This prospective study includes 137 patients newly diagnosed with de novo DLBCL positive to HCV infection in South Egypt Cancer Institute, Assiut University Hospital, and Health Insurance Hospital in Assiut. This study protocol was approved by the institutional review boards of each participating institute and complied with all of the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki. Patients were excluded if they were positive for hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), hepatitis B core antibody (anti-HBc), or for human immunodeficiency virus. Patients with primary central nervous system lymphoma, primary testicular lymphoma, and intravascular large-cell lymphoma were also excluded.

Treatment and response assessment

All of the DLBCL patients with HCV infection during the period received chemotherapy regimens including CHOP, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone ± rituximab. Patients with stage I and stage II bulky diseases received radiotherapy after chemotherapy. Disease stage was evaluated by using the Ann Arbor staging system. Liver and spleen involvement was diagnosed by imaging lymphoma invasion, such as nodular lesions or heterogeneous concentrations. Chemotherapy sensitivity was defined according to standard volume criteria, by using computed tomography.

Liver function tests and HCV viral markers

In all of the patients enrolled, pre-treatment levels of alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and their highest levels up to 6 months after completing chemotherapy were collected for analysis. Hepatic toxicity was defined by the National Cancer Institute of Canada criteria, and severe hepatic toxicity as an increase in transaminase levels (AST or ALT, grade 3 or 4; >5.0 X ULN). To assess impaired hepatic synthesis, serum total bilirubin (T-Bil), albumin, prothrombin time, and platelet counts were collected at the time of DLBCL diagnosis and 6 months from treatment. Serum HCV RNA load was determined by quantitative reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction

Statistical analysis

Comparisons among groups were performed with the t-test, the χ22 test, and Fisher's exact test. The tests were bilateral. The differences were considered significant at P < 0.05. Survival curves for the patients were calculated by the Kaplan–Meier method. Statistical analysis was performed with SAS software version 6.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). Progression-free survival (PFS) was calculated from the treatment initiation date to the date of documented disease progression, relapse, or the end date of the study. Non-lymphoma-related deaths were censored for PFS. Overall survival (OS) was calculated from the treatment initiation date until death from any cause or the last follow-up.

Result

Patients characteristics

Our study includes 137 newly diagnosed DLBCL positive to HCV compared with the second group according to treatment strategy (R-CHOP vs. CHOP). No significant difference was found between both groups in the age of the patients and sex predilection or staging at presentation. The patients who were HCV-positive at the time of DLBCL diagnosis in both groups have no significant difference also in the level of lactate dehydrogenase levels (P = 0.067), more than two extranodal sites (P = 0.75), or in the international prognostic index (P = 0.87) ().

Table 1. Patients characteristics

Hepatic toxicity

The parameters of the liver function test were evaluated in DLBCL positive to HCV infection and were compared according to treatment line (R-CHOP vs. CHOP), our result showed significant increase in serum T-Bil, ALT, and AST in DLBCL positive for HCV receiving R-CHOP than DLBCL patients who were HCV-positive treated with CHOP. Of the 68 patients who were HCV-positive treated with R-CHOP, (28of 68, 41%) had severe hepatic toxicity, compared with (13 of 69, 18%) of those who were DLBCL patients who were HCV-positive treated with CHOP (P = 0.001). Our result revealed that the addition of rituximab to the chemotherapy in DLBCL patients positive to HCV infection was a significant risk factor for severe hepatic toxicity ().

Table 2. Liver function test in DLBCL lymphoma according to treatment line

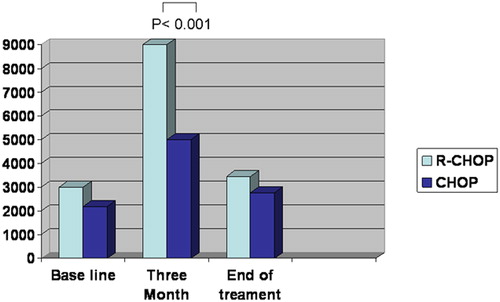

Serum HCV RNA was collected at baseline before treatment, 3 months from treatment, and at the end of treatment for both groups. Our results show significant increase in HCV serum level in the group treated by R-CHOP at 3 months in comparison with baseline which began to decline at the end of the treatment P = 0.001 ().

Survival analysis

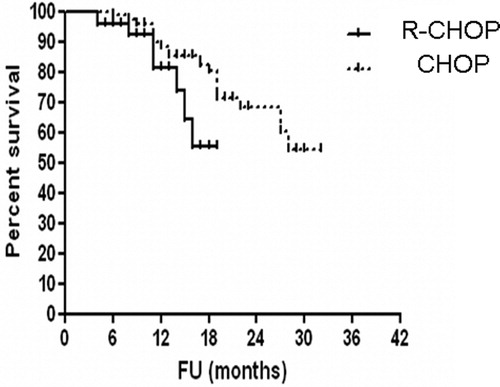

The median time of follow-up was 36 month range from (5–42 months). The PFS tended to be worse in patients who were DLBCL HCV-positive treated with R-CHOP than in those who were DLBCL HCV-positive treated with CHOP (PFS at 36 months, 55% for RCHOP vs. 80.5% for CHOP, P = 0.0021 (log-rank test), hazard ratio (HR): 2.661, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.269–5.582.) (). Complete remission rate was 69% in DLBCL HCV-positive treated with R-CHOP and 75% in DLBCL HCV-positive treated with CHOP.

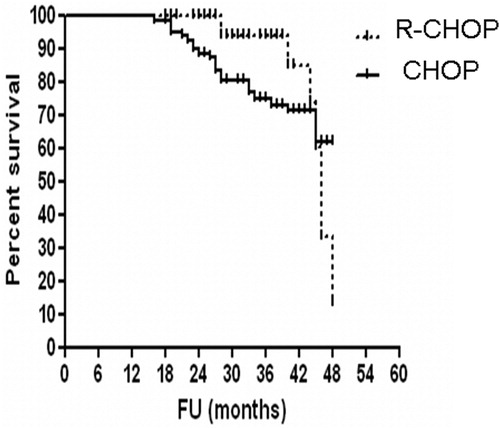

In HCV-positive DLBCL, there is a significant difference in OS between DLBCL patients treated with R-CHOP vs. patients treated with CHOP (4-year OS, 56% for R-CHOP group vs. 70.5% for CHOP, P = 0.0021 (log-rank test), HR: 2.661, 95% CI: 1.269–5.582.) ().

Discussion

In our study, we compare the patients hepatic toxicity profile and the outcome of DLBCL infected by HCV according to treatment line R-CHOP vs. CHOP. We found that HCV-positive DLBCL treated with R-CHOP have high incidence of hepatic toxicity and worse PFS survival in comparison with HCV-positive DLBCL treated with CHOP and also significance in OS. This first study compares the outcome of HCV-positive DLBCL treated with and without rituximab.

High prevalence of HCV among newly diagnosed DLBCL patients, which is supported by another report,Citation11 high prevalence of HCV in NHL from (9–32%), and also due to the high endemicity of HCV among the Egypt population.Citation1,Citation2 In accordance with the previous reports,Citation5–Citation7 HCV-positive patients in the present unmatched study had more aggressive tumor behavior at baseline and more frequent extranodal involvement. The mechanism underlying the association of HCV infection with aggressive tumor behavior is not well understood.

Our study showed that the group of patients treated with R-CHOP has significant high incidence of hepatic toxicity grade (3–4) (28 vs. 18%, P value 0.001), and that these hepatic toxicities led to the modification and the discontinuation of immunochemotherapy, resulting in lymphoma progression. Careful monitoring of the hepatic function should, thus, be recommended for HCV-positive patients, particularly those with high levels of pre-treatment liver enzyme. A recent analysis also showed an increase in hepatic toxicity in HCV-positive patients with B-cell lymphoma.Citation12 Besson et al.Citation5 found a higher incidence of hepatic toxicity deaths among HCV-positive DLBCL patients compared with HCV-negative patients, although this study was conducted on patients treated with more aggressive chemotherapy than the standard regimen. In contrast, in the pre-rituximab era, several series showed good tolerance to standard chemotherapy for HCV-infected patients with lymphoma.Citation6,Citation7,Citation13 However, these previous reports did not include the control group of HCV-negative patients, In addition, they did not exclude HBsAg-positive patients, known to be a high-risk population for severe hepatic injury. These data supported by the monitoring of the HCV viral load demonstrated a marked enhancement in HCV replication, and it is suggested that increased HCV expansion results in severe hepatic toxicity in patients receiving R-CHOP.Citation5,Citation14

We found in this study significant difference in PFS and OS in HCV-positive DLBCL treated with R-CHOP vs. patients treated with CHOP, no previous data were available probably due to the fact that increase in the incidence of hepatic toxicity led to several treatment discontinuations, dose reductions, and delays of chemotherapy and also in the present study it was found that HCV-positive patients exhibited more aggressive baseline behavior in contrast to previous reportsCitation5,Citation14–Citation16 which suggested that the combined use of rituximab and chemotherapy poses an additional risk for exacerbation of HCV infection because increased viral replication results in severe hepatic toxicity.Citation17–Citation19

In conclusion, a significant proportion of patients with HCV-positive DLBCL treated by rituximab develop liver toxicity often leading to interruption of treatment hence hepatic function should be carefully monitored in patients who are HCV-positive and receive immunochemotherapy. This is an important limit to the application of effective modern immunochemotherapy. HCV-positive lymphomas represent a distinct clinical subset of NHL that deserves specific clinical approach to limit liver toxicity and ameliorate survival. Well-designed multicentric studies will be necessary to determine whether early detection and prevention of HCV replication would provide improved disease management for HCV-infected patients receiving immunochemotherapy.

References

- Ferreri AJ, Ernberg I, Copie-Bergman C. Infectious agents and lymphoma development: molecular and clinical aspects. J Intern Med. 2009;265:421–38.

- Nieters A, Kallinowski B, Brennan P, Ott M, Maynadié M, Benavente Y, et al. Hepatitis C and risk of lymphoma: results of the European multicenter case-control study EPILYMPH. Gastroenterology 2006;131:1879–86.

- Hermine O, Lefrère F, Bronowicki JP, Mariette X, Jondeau K, Eclache-Saudreau V, et al. Regression of splenic lymphoma with villous lymphocytes after treatment of hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:89–94.

- Vallisa D, Bernuzzi P, Arcaini L, Sacchi S, Callea V, Marasca R, et al. Role of anti-hepatitis C virus (HCV) treatment in HCV-related, low-grade, B-cell, non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: a multicenter Italian experience. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:468–73.

- Besson C, Canioni D, Lepage E, Pol S, Morel P, Lederlin P, et al. Characteristics and outcome of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in hepatitis C virus-positive patients in LNH 93 and LNH 98 Groupe d'Etude des Lymphomes de l'Adulte programs. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:953–60.

- Visco C, Arcaini L, Brusamolino A, Merli M, et al. Distinctive natural history in hepatitis C virus positive diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: analysis of 156 patients from northern Italy. Ann Oncol. 2006;17:1434–40.

- Kawatani T, Suou T, Tajima F, Ishiga K, Omura H, Endo A, et al. Incidence of hepatitis virus infection and severe liver dysfunction in patients receiving chemotherapy for hematologic malignancies. Eur J Haematol. 2001;67(1):45–50.

- Coiffier B, Lepage E, Briere J, Herbrecht R, Tilly H, Bouabdallah R, et al. CHOP chemotherapy plus rituximab compared with CHOP alone in elderly patients with diffuse large-B-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(4):235–42.

- Pfreundschuh M, Kuhnt E, Trümper L, Osterborg A, Trneny M, Shepherd L, et al. CHOP-like chemotherapy with or without rituximab in young patients with good-prognosis diffuse large-B-cell lymphoma: 6-year results of an open-label randomised study of the MabThera International Trial (MInT) Group. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12(11):1013–22.

- Nishimori H, Matsuo K, Maeda Y, Nawa Y, Sunami K, Togitani K, et al. The effect of adding rituximab to CHOP-based therapy on clinical outcomes for Japanese patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: a propensity score matching analysis. Int J Hematol. 2009;89(3):326–31.

- Zuckermann L, Yashikawa G. Hepatitis C infection and B cell NHL. Cancer 1997;83:1224–30.

- Arcaini L, Merli M, Passamonti F, Bruno R, Brusamolino E, Sacchi P, et al. Impact of treatment-related liver toxicity on the outcome of HCV-positive non-Hodgkin's lymphomas. Am J Hematol. 2010;85(1):46–50.

- Zuckerman E, Zuckerman T, Douer D, Qian D, Levine AM. Liver dysfunction in patients infected with hepatitis C virus undergoing chemotherapy for hematologic malignancies. Cancer 1998;83(6):1224–30.

- Ennishi D, Maeda Y, Niitsu N, Kojima M, Izutsu K, Takizawa J, et al. Hepatic toxicity and prognosis in hepatitis C virus-infected patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with rituximab-containing chemotherapy regimens: a Japanese multicenter analysis. Blood 2010;116(24):5119–25.

- Besson C, Canioni D, Lepage E, Pol S, Morel P, Lederlin P, et al. Characteristics and outcome of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in hepatitis C virus-positive patients in LNH 93 and LNH 98 Groupe d'Etude des Lymphomes de l'Adulte programs. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(6):953–60.

- Luca A, Michele M, Francesco P, Raffaele B, Ercole B, Paolo S, et al. Impact of treatment-related liver toxicity on the outcome HCV-positive non-Hodgkin's lymphomas. Am J Hematol. 2010;85:46–50

- Lake-Bakaar G, Dustin L, McKeating J, Newton K, Freeman V, Frost SD. Hepatitis C virus and alanine aminotransferase kinetics following B-lymphocyte depletion with rituximab: evidence for a significant role of humoral immunity in the control of viremia in chronic HCV liver disease. Blood 2007;109(2):845–6.

- Hsieh CY, Huang HH, Lin CY, Chung LW, Liao YM, Bai LY, et al. Rituximab-induced hepatitis C virus reactivation after spontaneous remission in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(15):2584–6.

- Aksoy S, Abali H, Kilickap S, Erman M, Kars A. Accelerated hepatitis C virus replication with rituximab treatment in a non-Hodgkin's lymphoma patient. Clin Lab Haematol. 2006;28(3):211–4.