Abstract

Objective

Evaluate adherence to clotting factor treatment and associated outcomes for patients with hemophilia using an integrated delivery database.

Methods

This was a retrospective, observational study tracking patients between 2006 and 2011. Patients with diagnosis codes for hemophilia were identified. Bleeding and complication rates were annualized over the study period. Medication adherence was assessed using prescription claims for clotting factors by examining sequential time periods of 180 days for each patient's continuous enrollment. Adherence within the time period was calculated using the ‘days supply’ field divided by 180 days. Under the assumption that severe patients should be treated prophylactically, patients were considered adherent within the time period if the ratio of ‘days supply’ to observed days was 60% or greater.

Results

A total of 207 patients (74.9 and 25.1% hemophilia A and B, respectively) met the inclusion/exclusion criteria. There were 101 (48.8%) mild, 32 (15.5%) moderate, and 74 (35.7%) severe patients with hemophilia. The percentage of time periods where adherence to clotting factors was 60% or greater was 14% (SD = 28%) for mild disease, 21% (SD = 32%) for moderate disease, and 51% (SD = 36%) for severe disease. Among patients with severe disease, 27 (36.5%) were adherent ≤30% of time periods, 22 (29.7%) adherent 31–70% of the time periods, and 25 (33.8%) were adherent ≥71% of time periods. Joint bleeding episodes and hospitalizations were uncommon events among the three groups.

Conclusions

Among patients with severe disease, the majority (66.2%) were adherent <70% of the time.

Introduction

Hemophilia A and B are congenital bleeding disorders requiring lifelong treatment. Hemophilia A is a recessively inherited coagulation disorder due to an X-chromosome mutation carried by females and males, affecting ∼1 in 5000 males.Citation1 It is caused by mutations and/or deletions in the clotting factor 8 gene resulting in decreased Factor VIII activity.Citation1,Citation2 Hemophilia B is a deficiency in clotting factor IX and is an X-chromosome-linked bleeding disorder that affects ∼1 in 30 000 males worldwide.Citation1,Citation3 Individuals with severe hemophilia A or B experience frequent and often recurrent, spontaneous bleeding into the joints, leading to joint damage and severe disability.Citation4 This damage is progressive and can lead to severely limited mobility of joints, muscle atrophy, and chronic pain and require orthopedic surgery. Joint damage can result from only a few joint bleeds.Citation5,Citation6 The severity of the bleeding may also pose a life-threatening situation (e.g. intracranial hemorrhage, other internal bleeding) for a patient if not treated appropriately. Adult hemophilia patients often have reduced physical functioning compared to pediatric patients due to joint damage.Citation7 In a landmark study, Manco-Johnson et al.Citation8 demonstrated that prophylaxis with factor VIII in pediatric patients clearly reduced joint bleeding in young boys further demonstrating the benefits of prophylaxis when started early.

Given the low prevalence and incidence rates for hemophilia and disparate processes of care, it has been difficult to assess the quality of care and related outcomes. In the USA, patients are often referred to hemophilia treatment centers for comprehensive care provided by a multidisciplinary team. However, healthcare often becomes fragmented by different health systems, home treatment, the independence of patients to ‘choose’ between on-demand or prophylactic treatment, and patient delay in seeking hospital care with bleeding episodes. Routine commercial claims databases may be limited in integrating data across different healthcare providers. However, some patients, such as dependents of Department of Defense (DOD) employees, receive care through integrated delivery systems. Using data from these integrated systems may provide a better understanding of how hemophilia patients are managed through a health system. Furthermore, the associated outcomes and economic impact of various treatment options can inform both policy and individual treatment decisions.

The purpose of this study was to evaluate adherence to clotting factor prescriptions and associated outcomes for patients with factor VIII or factor IX deficiencies over a 5-year period within the US DOD medical database. Specifically, this study described the epidemiology (e.g. demographics and severity) and associated treatment pathways for hemophilia patients with factor VIII or factor IX deficiency who received medical care at a DOD medical facility.

Methods

This study was a retrospective, observational study utilizing electronic medical records and administrative encounters/claims data to determine the demographic characteristics (e.g. age, sex) and treatment patterns of factor VIII and factor IX products in patients with hemophilia. The observational period was up to 5 years from 1 October 1 2006 through 30 September 2011. Persons were eligible for inclusion if they had two healthcare encounters with a diagnosis of hemophilia (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth revision (ICD-9) code 286.0 for hemophilia A (factor VIII deficiency) and 286.1 for hemophilia B (factor IX deficiency)). For eligible subjects, all medical and pharmacy encounters/claims were obtained over the 5-year period of the study. Research data were derived from an approved Naval Medical Center, Portsmouth, VA Institutional Review Board (IRB NMCP.2012.0016) protocol.

To determine the severity of disease, a review of the electronic medical records was conducted by a trained nurse using a standardized data collection instrument. Severity was determined by factor level from documented lab reports. Severity was classified into mild (5–50% normal clotting activity), moderate (1–5% normal clotting activity), or severe (<1% normal clotting activity). Once the data were collected, administrative and record review data were stripped of patient identifiers and integrated into an analytical dataset.

Further eligibility required at least two medical or pharmacy encounters/claims for either factor VIII (Advate, Helixate FS, Kogenate FS, Recombinate, ReFacto, Xyntha, Hemofil M, Monoclate-P, or Corifact) or factor IX (AlphaNine, MonoNine, Immunine, or BeneFIX) replacement factors within the study period. Two prescriptions were required to prevent misclassification and also for adherence calculations. Finally, persons must have had at least 6 months of continuous enrollment in the DOD healthcare system.

Persons were ineligible for inclusion if their medical records indicated a diagnosis and/or treatment of von Willebrand disease. These persons were defined as the following: (1) one or more prescriptions/claims for Humate-P or Wilate; (2) young persons (<50 years of age) receiving Alphanate or Koate; (3) one or more healthcare encounters with a diagnosis code specific to von Willebrand disease; or (4) older persons (age >50) receiving desmopressin therapy.

Persons with hemophilia A or B that were also receiving factor VIII inhibitor bypassing activity (FEIBA) and recombinant factor VIIa (rFVIIa, Novoseven) were excluded from the analysis as they have unique clinical and treatment characteristics.Citation9

Descriptive analyses were conducted to examine distributions of age and gender. Bleeding events were identified by ICD-9 codes. Bleeding-related hospitalizations were identified using the inpatient DOD database. In assessing bleeding complications, these events were annualized to determine the number of events over a 12-month period.

The primary outcome of interest in this study was adherence to clotting factor therapies. Medication adherence was assessed using prescription claims for clotting factors by examining sequential time periods of 180 days within each patient's continuous enrollment. Adherence was calculated using the ‘days supply’ field for all pharmacy claims divided by the180-day time period. All persons were required to have at least one observation period of 180 days. For each patient, up to 10 observational windows were evaluated. The vast majority (N = 171, 82.6%) of persons had 10 observation periods. Individuals were considered adherent if the percentage of ‘days supply’ of product to the observed 180-day time period was 60% or greater. Overall, patient adherence was determined by analyzing the proportion of time periods during which the patient met 60% adherence criteria.

Statistical analyses were conducted using Stata 12.1. Chi-square tests were used to compare dichotomous variables and independent t-tests were used to compare continuous variables. Analysis of variance and Kruskal–Wallis tests were used to compare continuous variables with more than two groups. A Sidak post hoc test was used to determine where statistical differences in dependent variables were found. Multivariate regression analyses were used to control for other independent variables. An α level of 0.05 was used to determine statistical significance.

Results

There were 214 persons that met eligibility criteria and for whom medical record data were available to classify the severity of disease. Seven persons were excluded from the analysis because there was FEIBA or rFVIIa use (indicating they likely had inhibitors), leaving 207 patients eligible for analysis. summarizes the descriptive information for the study sample. Overall, the median age was 7.0 years, range <1–61. There were 101 (48.8%) persons with mild disease, 32 (15.5%) with moderate disease, and 74 (35.7%) with severe disease. A total of 155 (74.9%) persons had hemophilia A (factor VIII deficiency) and 52 (25.1%) persons had hemophilia B (factor IX deficiency). The vast majority (N = 202, 97.6%) were male. Persons with severe hemophilia were significantly younger (median 4.0, range <1–43) compared to patients with mild disease (median 9.0, range <1–61, P = 0.011). There were no differences between mild and moderate or moderate and severe persons with hemophilia with respect to age.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics

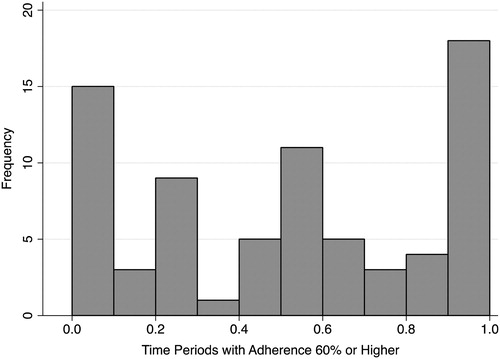

The percentage of time periods where adherence to clotting factors was 60% or greater was 14% (SD = 28%) for persons with mild disease, 21% (SD = 32%) for moderate disease, and 51% (SD = 36%) for severe disease. Adherence for mild and moderate were both significantly lower than severe patients (). Among persons with severe disease (n = 74), there were multiple peaks across the distribution, with 27 (36.5%) persons adherent for ≤30% of the time periods, 22 (29.7%) adherent 31–70% of the time periods, and 25 (33.8%) persons were adherent >70% of the time (). Multivariate analysis found that age (P = 0.337) and hemophilia type (A or B, P = 0.928) were not significant in identifying differences in the 60% or greater adherent time periods.

Table 2. Time periods at least 60% adherence to factor therapy by hemophilia severity

summarizes the annualized total bleeding episodes, joint bleeding episodes, and total hospitalization episodes by hemophilia severity. Overall, these were uncommon events documented in the medical database. For both total bleeding episodes and joint bleeding episodes, there were no significant differences between hemophilia severity categories (P = 0.388 and P = 0.200, respectively). In addition, there was no difference in hospitalization episodes by severity (P = 0.920). Similarly, when the data were stratified by age groups, there was no difference in the recorded number of total bleeding (P = 0.206) or joint bleeding episodes (P = 0.904). However, when the hospitalization rate was stratified by age group, patients in the 31–40 age group had significantly more documented hospitalizations (1.9 ± 3.2) than persons 0– < 12 years of age (0.26 ± 0.54) or 12–18 years of age (0.12 ± 0.20) (P = 0.001, P < 0.001, respectively). Overall, catheter port infections were uncommon within the medical database, as there were only 0.03 ± 0.20 episodes captured per year.

Table 3. Annual bleeding episodes by hemophilia severity

Discussion

Adherence to clotting factor treatment is extremely variable, with the vast majority of persons with severe disease having low rates of adherence as documented in this database analysis. In contrast to randomized controlled trials where adherence is enforced and monitored closely, this study is an effectiveness analysis that describes factor consumption in actual practice settings. The wide dispersion shown in clearly demonstrates that most patients with severe hemophilia are not adherent to a continuous regimen despite receiving the benefits of a comprehensive healthcare network established by the US DOD. In addition, their young age (median = 4.0 years (range <1–43)) would lead to the assumption that parental involvement would result in better compliance. The adherence findings in this study are important to note given the evidence documenting that prophylactic factor regimens have been shown to reduce joint damage especially in young children.Citation8,Citation10 Prophylactic factor regimens have been shown to prevent bleeding and that when prophylaxis is discontinued, bleeding episodes increase.Citation8,Citation11–Citation14 Since 2003, there has been an international focus to emphasize the role of prophylactic therapy in severe hemophilia.Citation15 Prevention of bleeding into joints is important as one to two bleeding episodes can trigger irreversible joint damage and a decrement in health-related quality of life.Citation6,Citation16 The Medical and Scientific Advisory Council of the National Hemophilia Foundation recommends prophylaxis as optimal therapy for patients with severe hemophilia.Citation17

This analysis in the DOD identified 207 patients with up to 5 years of healthcare data. The documented hemophilia population was largely children, male, and 74.9% of the population had hemophilia A. Patients in the 31–40 years age group had significantly more documented bleeding-related hospitalizations than noted in the 0–11 or 12–18 age group. This may be due to clinical complications from hemophilia or reasons unrelated to the condition. It is unknown why the adult group had a higher hospitalization rate than children; however, it is possible that adults with longer standing chronic arthropathy are more prone to bleeding, and may have encountered more bleeding complications than younger patients.

However, despite the documented benefits of factor prophylaxis in severe hemophilia, the literature has shown marked variation in patient adherence. Because of the difficulties in specifying treatment regimen, the majority of studies to date evaluate adherence through patient surveys. Duncan et al.Citation18 used a multidimensional validated questionnaire with patients with severe hemophilia and estimated that patients administered 86.7% of recommended factor infusions. De Moerloose et al.Citation19 distributed a questionnaire to patients with severe hemophilia in six European countries and estimated that 80–87% of patients were adherent with their prescribed factor regimen. A US study by Duncan et al.Citation20 found that pediatric patients had better adherence than adults and that children <12 years of age had higher adherence than patients with 12–18 years of age. The authors found that pediatric patients infused by family members had higher adherence than pediatric self-infusers. Epstein et al.Citation21 noted that factor VIII prophylaxis use decreased with increasing patient age and that factor VIII use was higher with patients with severe hemophilia. In addition, DuTreil et al.Citation16 found that patients who were adherent to high intensity therapy had lower bodily pain scores compared to patients with low adherence to these regimens.

In contrast, not all studies have shown high adherence rates with factor products. Lindvall et al.Citation22 found that 41% of severe and moderate hemophilia patients receiving care at hemophilia treatment centers had decided to not follow the prophylactic factor therapy. The authors found that the mean age when a patient had the responsibility for his disease and treatment was 14.1 years. The patients indicated that the most difficult aspects of their disease were to remember to administer the factor, perform the venipuncture, having restrictions regarding physical activities, and having to tell others about their disease. Similarly, Hacker et al.Citation23 noted that 41% of patients did not rate their adherence as excellent. ThornburgCitation24 conducted a study with physicians working in pediatric hemophilia treatment centers and noted that only 57% of prescribers who prescribed prophylaxis factor regimens thought that >75% of patients infused at least 80% of their prescribed prophylaxis regimen.

Although prophylactic factor regimens have been shown to be important in preventing chronic joint damage for patients with severe hemophilia, effective implementation can be impaired by poor adherence with prescribed infusions.Citation25 Consideration should be given to methods to improve education and adherence with factor regimens for patients and their families. Additional prospective studies are needed to identify ways to improve adherence to prophylactic regimens for patients with severe disease. In addition, since adherence with current factor regimens is suboptimal, new, novel, long-acting factor products may lead to improved patient adherence, which in turn may prevent chronic joint damage.

Also, some bleeding-related hospitalizations may have been prevented if break-through bleeding episodes were managed with home treatment and did not require medical attention. The rate of hospitalization and bleeding events observed in this study were relatively low, and may be attributable to good clinical care and easy access to healthcare services. In addition, the lack of events might be attributable to the very young cohort that was studied.

Although infusion records of factor therapy designating treatment regimens over the 5-year study period were not available, we utilized the claims data to measure adherence in severe hemophilia patients. A ratio was calculated based on the amount of factor dispensed to patients versus the recorded ‘days supply’ to indicate the expected duration. This methodology is the best way to utilize claims data to estimate treatment adherence. This approach was validated using severity of hemophilia as a proxy. The results demonstrated that severe patients had an average coverage ratio of 51% (SD = 36%) versus those with moderate 21% (SD = 32%) and mild 14% (SD = 28%) hemophilia which mirrors the clinical treatment where severe hemophilia patients receive more continuous treatment versus those with milder forms. Consequently, the ‘days supply’ field in the pharmacy claims has become a more reliable measure, especially with expensive, chronic medications. Insurance and pharmacy benefit managers routinely use this information when making coverage decisions.

There are several limitations with this study. Frequency of factor administration was not available from the medical charts, so adherence was estimated using the ‘days supply’ provided on the billing record. ‘Days supply’ values were entered by pharmacy per standard US billing practices for pharmaceutical products. Another limitation was that patients may have had inhibitors that could not be identified with the bypassing agents. In addition, there may have been some patients in the sample that received plasma-derived products (e.g. possible patients with inhibitors) that were used as a surrogate to exclude patients with von Willebrand disease. An additional limitation is that it was not possible to distinguish between prophylaxis or on-demand therapy. During the 5 years of data collection, a specific patient may have received some therapy as prophylaxis and other therapy as on-demand. In addition, as previously noted, break-through bleeding episodes managed at home and not requiring medical attention would not be detected in this analysis.

Conclusion

Adherence to administration of clotting factors varies widely across hemophilia patients. With the current clinical guidelines promoting prophylactic factor regimens, it would be expected that most patients with severe disease would be on prophylactic regimens. This analysis suggests that many young patients are not adherent with prophylactic therapy. Among persons with severe disease, adherence to clotting factors was variable, with the majority of persons (66.2%) being adherent <70% of the time. Future research is needed to examine interventions that would enhance adherence with prophylactic factor regimens.

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Navy, DOD, or the United States Government.

Disclaimer statements

Contributors EPA and DCM designed the project and conducted the statistical analysis. EPA, DCM, SK and MJW were involved with writing and editing the manuscript.

Funding This project was funded by Biogen Idec. No products manufactured by Biogen Idec were included in the analysis.

Conflicts of interest EPA and DCM were consultants to Biogen Idec through Strategic Therapeutics, LLC for this project. SK is an employee and shareholder of Biogen Idec. MJW has no interests which might be perceived as posing a conflict or bias.

Ethics approval Research data were derived from an approved Naval Medical Center, Portsmouth, VA Institutional Review Board (IRB NMCP.2012.0016) protocol.

Acknowledgments

Maj Jacob Wessler is a military service member. This work was prepared as part of his official duties.

References

- Mannucci PM, Tuddenham EG. The hemophilias – from royal genes to gene therapy. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(23):1773–9.

- Bolton-Maggs PH, Pasi KJ. Haemophilias A and B. Lancet 2003;361(9371):1801–9.

- Evatt BL. Demographics of hemophilia in developing countries. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2005;31(5):489–94.

- Rodriguez-Merchan EC. Management of musculoskeletal complications of hemophilia. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2003;29(1):87–96.

- Valentino LA. Secondary prophylaxis therapy: what are the benefits, limitations and unknowns? Haemophilia 2004;10(2):147–57.

- Kilcoyne RF, Nuss R. Radiological assessment of haemophilic arthropathy with emphasis on MRI findings. Haemophilia 2003;9( Suppl 1):57–64.

- Zhou ZY, Wu J, Baker J, Curtis R, Forsberg A, Huszti H, et al. Haemophilia utilization group study – Part Va (HUGS Va): design, methods and baseline data. Haemophilia 2011;17(5):729–36.

- Manco-Johnson MJ, Abshire TC, Shapiro AD, Riske B, Hacker MR, Kilcoyne R, et al. Prophylaxis versus episodic treatment to prevent joint disease in boys with severe hemophilia. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(6):535–44.

- Valentino LA, Pipe SW, Tarantino MD, Ye X, Xiong Y, Luo MP. Healthcare resource utilization among haemophilia A patients in the United States. Haemophilia 2012;18(3):332–8.

- Blanchette VS. Prophylaxis in the haemophilia population. Haemophilia 2010;16( Suppl 5):181–8.

- Walsh CE, Valentino LA. Factor VIII prophylaxis for adult patients with severe haemophilia A: results of a US survey of attitudes and practices. Haemophilia 2009;15(5):1014–21.

- Tagliaferri A, Franchini M, Coppola A, Rivolta GF, Santoro C, Rossetti G, et al. Effects of secondary prophylaxis started in adolescent and adult haemophiliacs. Haemophilia 2008;14(5):945–51.

- Iorio A, Marchesini E, Marcucci M, Stobart K, Chan AK. Clotting factor concentrates given to prevent bleeding and bleeding-related complications in people with hemophilia A or B. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(9):CD003429.

- Shapiro A, Gruppo R, Pabinger I, Collins PW, Hay CR, Schroth P, et al. Integrated analysis of safety and efficacy of a plasma- and albumin-free recombinant factor VIII (rAHF-PFM) from six clinical studies in patients with hemophilia A. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2009;9(3):273–83.

- Berntorp E, Astermark J, Bjorkman S, Blanchette VS, Fischer K, Giangrande PL, et al. Consensus perspectives on prophylactic therapy for haemophilia: summary statement. Haemophilia 2003;9( Suppl 1):1–4.

- du Treil S, Rice J, Leissinger CA. Quantifying adherence to treatment and its relationship to quality of life in a well-characterized haemophilia population. Haemophilia 2007;13(5):493–501.

- Council MaSA. MASAC recommendation concerning prophylaxis (regular administration of clotting factor concentrate to prevent bleeding): National Hemophilia Foundation. 2007 [2013 Jan 3]. MASAC document #179. Available from: http://www.hemophilia.org/NHFWeb/MainPgs/MainNHF. aspx?menuid=57&contentid=1007.

- Duncan N, Kronenberger W, Roberson C, Shapiro A. VERITAS-Pro: a new measure of adherence to prophylactic regimens in haemophilia. Haemophilia 2010;16(2):247–55.

- De Moerloose P, Urbancik W, Van Den Berg HM, Richards M. A survey of adherence to haemophilia therapy in six European countries: results and recommendations. Haemophilia 2008;14(5):931–8.

- Duncan N, Shapiro A, Ye X, Epstein J, Luo MP. Treatment patterns, health-related quality of life and adherence to prophylaxis among haemophilia A patients in the United States. Haemophilia 2012;18(5):760–5.

- Epstein J, Xiong Y, Woo P, Li-McLeod J, Spotts G. Retrospective analysis of differences in annual factor VIII utilization among haemophilia A patients. Haemophilia 2012;18(2):187–92.

- Lindvall K, Colstrup L, Wollter IM, Klemenz G, Loogna K, Gronhaug S, et al. Compliance with treatment and understanding of own disease in patients with severe and moderate haemophilia. Haemophilia 2006;12(1):47–51.

- Hacker MR, Geraghty S, Manco-Johnson M. Barriers to compliance with prophylaxis therapy in haemophilia. Haemophilia 2001;7(4):392–6.

- Thornburg CD. Physicians' perceptions of adherence to prophylactic clotting factor infusions. Haemophilia 2008;14(1):25–9.

- Thornburg CD. Prophylactic factor infusions for patients with hemophilia: challenges with treatment adherence. J Coagul Disord. 2010;2(1):9–14.