Abstract

Objectives

This study evaluated the role of an automated anemia notification system that alerted providers about anemic pre-operative patients.

Methods

After scheduling surgery, the alert program continuously searched the patient's laboratory data for hemoglobin value(s) in the medical record. When an anemic patient according to the World Health Oganization's criteria was identified, an email was sent to the patient's surgeon, and/or assistant, and/or patient's primary care physician suggesting that the anemia be managed before surgery.

Results

Thirteen surgeons participated in this pilot study. In 11 months, there were 70 pre-surgery anemia alerts generated on 69 patients. The surgeries were 60 orthopedic, 7 thoracic, 2 general surgery, and 1 urological. The alerts were sent 15±10 days before surgery. No pre-operative anemia treatment could be found in 37 of 69 (54%) patients. Some form of anemia management was found in 32 of 69 (46%) patients. Of the 23 patients who received iron, only 3 of 23 (13%) of these patients started iron shortly after the alert was generated. The alert likely resulted in the postponement of one surgery for anemia correction.

Discussion

Although anemia diagnosis and management can be complex, it was hoped that receipt of the alert would lead to the management of all anemic patients. Alerts are only effective if they are received and read by a healthcare provider empowered to treat the patient or to make an appropriate referral.

Conclusions

Automated preoperative alerts alone are not likely to alter surgeons' anemia management practices. These alerts need to be part of a comprehensive anemia management strategy.

Introduction

Anemia is a common condition that affects a significant proportion of patients undergoing a variety of surgical procedures.Citation1–Citation6 It is an important risk factor for many medical conditions such as myocardial ischemia.Citation7 Pre-operative anemia is also a risk factor for requiring a peri-operative allogeneic transfusion, requiring readmission after surgery and for longer lengths of hospital stay.Citation8 Thus, anemic patients should be identified and their anemia corrected before surgery. It is a common practice for patients to have pre-operative laboratory testing, including measuring their hemoglobin (Hb) concentration, drawn around the time that their surgery is scheduled. However, if the results of this testing are not investigated before the day of surgery, then there are very few options for anemia correction other than allogeneic red blood cell (RBC) transfusion at that time. While RBC transfusion is generally a safe procedure, several adverse events can occur, so the timely identification and management of pre-operative anemia is important in transfusion avoidance.

Patient blood management (PBM) is a new concept that is becoming widely adopted at transfusion services and hospitals around the world. It uses a multidisciplinary approach to optimize patients before procedures so that transfusions can be avoided, and using pharmaceuticals instead of blood products to correct anemia and coagulopathies.Citation9 PBM has applications in both medical and surgical patients, and evidence from large randomized controlled trials serves as the underpinning for transfusion thresholds in these patients.Citation10–Citation14 One component of a PBM program can be the implementation of processes and procedures to identify pre-operative patients who are anemic, diagnose the etiology of the anemia and correct it. One such initiative of the PBM committee at a multihospital regional healthcare system was to implement an automated alert that notified surgeons and primary care physicians (PCP) when an anemic patient has been scheduled for surgery. The intention of the alert was to identify the anemic patients so referrals could be made to specialists who would address the anemia, or the surgeon or PCP could manage the anemia themselves before the date of surgery. This report details the initial experience with automated pre-operative anemia alerts in a regional healthcare system.

Materials and methods

The computerized script that detects anemic pre-operative patients was developed locally by the healthcare system's information technology department. In this healthcare system, all surgeries were scheduled using the Surginet surgical scheduling software (Cerner Corp., Kansas City, MO, USA). The script was automatically activated at the time that a patient was scheduled for surgery. Upon activation, the script searched through the patient's laboratory data in Sunquest (Sunquest Information Systems, Phoenix, AZ, USA) and Quest laboratory information systems (Quest Diagnostics, Madison, NJ, USA) starting 45 days before the surgery and continuing daily until the day of surgery. The 45-day pre-operative length of time was chosen in light of the Joint Commission's initiative to ensure that all of the patient's pre-operative laboratory testing had been ordered between 14 and 45 days before surgery, and also to permit sufficient time to correct the anemia.

Anemia was defined using the World Health Oganization's criteria of a Hb value less than 12 g/dl for women and less than 13 g/dl for men.Citation15 If an anemic Hb value was detected by the script within 45 days of surgery, the program immediately sent an email to two recipients that had been designated before hand by the surgeon alerting them to the patient's Hb value and suggesting that the anemia should be corrected before the day of surgery. The most frequently designated recipients of the email alert included the surgeon, the surgeon's assistant, or the patient's PCP.

As a pilot project, 13 surgeons in the healthcare system representing a variety of specialties agreed to receive these alerts on all of their anemic patients between April 2013 and February 2014. There were no specific anemia management protocols or algorithms provided to the surgeons or the PCPs who received the alerts. In March 2014, electronic chart reviews were performed on these anemic patients to determine wheather receipt of the alert had led to the management of the patient's anemia. The chart review focused on any consultations or procedures that were made to address the anemia, any medications that the patient received to correct the anemia, and any surgery date prolongations that occurred as a result of the alerts. The Hb value that caused the alert, the date the alert was generated, and the scheduled surgery date were also recorded.

Although the alerts were triggered on anemic patients regardless of the nature of their surgery, some patients were excluded from this analysis. Excluded patients included those who were inpatients at the time that the alert was generated because it was felt that their procedures were likely to be urgent and therefore had insufficient time to correct the anemia, patients whose surgery was cancelled for any reason other than to allow for more time to correct the anemia, and patients whose Hb results were obtained more than 45 days prior to surgery as this value would not have been detected by the script and thus an alert would not have been sent.

After the pilot study was completed, all of the surgeons, their assistants, and the PCPs who participated in the alert pilot were invited to participate in an online and anonymous survey to provide feedback on their experience with the alerts.

Continuous variables were analyzed using descriptive statistics, and categorical variables were analyzed using Fisher's exact test (GraphPad version 6, San Diego, CA, USA). This protocol was approved by the University of Pittsburgh Total Quality Council, a division of the Institutional Review Board.

Results

Over the 11 months of this study, 120 pre-operative anemia alerts were generated on 119 patients. Fifty patients were excluded from the study as follows: 33 patients were inpatients at the time that the alert was generated, 7 had their surgery cancelled for reasons other than requiring additional time to correct the anemia, and 3 patients had Hb values obtained more than 45 days before their surgery date. Six patients were excluded because the recipient of the email alert was unknown, while one patient's anemia alert was sent months after the surgery occurred due to a technical error.

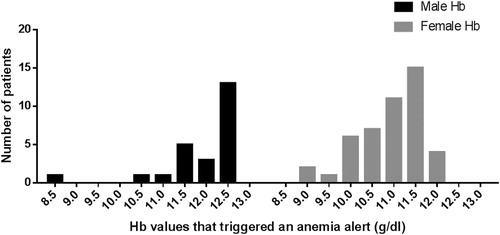

Thus, this analysis included 70 pre-surgery anemia alerts that were generated on 69 patients. One patient had two surgeries performed 4 months apart and had two alerts generated. There were 24 male and 45 female patients. The mean age of male patients was 66±13 years and the median Hb value that triggered the alert was 12.3 g/dl (range 8.4–12.7) (). The mean age of female patients was 66±12 years and the median Hb value that triggered the alert was 11.1 g/dl (range 8.8–11.9) (). The nature of the 70 procedures was as follows: 60 orthopedic, 7 thoracic, 2 general surgery, and 1 urological.

Figure 1. Distribution of pre-operative hemoglobin (Hb) values that triggered an alert. Values over each Hb concentration are within a range of ±0.25 g/dl of that concentration, i.e. there were four male patients with pre-operative Hb concentrations that triggered an alert between 11.25and 11.75 g/dl represented in the bar above 11.5 g/dl.

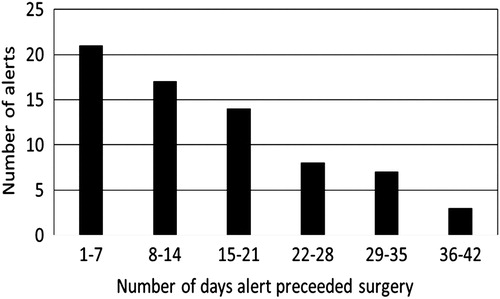

On average the 70 alerts were generated a mean of 15±10 days (mode = 1 day) before the scheduled date of surgery ().

Figure 2. Frequency of pre-operative anemia alerts sent in relation to the day of surgery. On average, the alerts were sent 15±10 days (mode=1 day) before the day of surgery.

No pre-operative anemia treatment could be found for 37 of 69 (54%) patients on whom an alert was generated (). The prescription of hematinic medications such as iron, folate, or B12 was identified in 32 of 69 (46%) patients; 24 patients received a single medication to correct their anemia while 8 patients received multiple medications. Of the 23 patients who received iron, only 3 of 23 (13%) of these patients started their iron shortly after the alert was generated. An immediate pre-operative Hb concentration was not drawn on these three patients. Thus it is not known if their anemia was corrected before their surgery. In 11 of 23 (48%) recipients, the iron initiation date could not be determined. The remaining 9 of 23 (39%) patients had already been on iron when the alert was generated. Folate and/or B12 was administered to 16 patients before the alert was sent; in one other patient the folate start date was unknown. No referrals for colonoscopy or endospcopy were found in the medical records of any of the patients.

Table 1. The nature of pre-operative anemia treatment

Although no reference to receipt of the alert was documented in the chart, the alert likely resulted in the postponement of one surgery so as to correct the anemia before surgery; this patient received intravenous (IV) iron prescribed by a hematologist to whom the patient was referred by their PCP after receiving the anemia alert. In addition, their surgery was cancelled shortly after receipt of the alert; this supports the suggestion that the alert led to the recognition of the anemia and the postponement of the surgery.

Of the 35 email invitations to participate in the post-pilot study evaluation, only six individuals completed the online survey within 8 weeks. Of the six respondents, five of six felt that the alert was sent to the correct individual, and five of six respondents felt that they preferred to manage their patient's anemia themselves without consulting other specialists. There were three respondents who provided reasons for not consulting anemia management specialists or managing the patient's anemia themselves; their responses included not receiving the alert, a recognition that their patient's anemia was being managed by someone else, and that the patient was not scheduled for high blood loss surgery.

Discussion

This healthcare system performs approximately 220 000 surgical procedures annually. Two separate local audits of a variety of pre-surgical patients revealed that approximately 25% of these patients were anemic (unpublished results), which is similar to published rates of pre-operative anemia.Citation8 This means that any process that addresses preoperative anemia correction needs to be robust enough to address up to 50 000 patients a year. To this end, an automated notification system was employed to inform surgeons and physicians about their anemic pre-operative patients. The intention of the alert was to stimulate an investigation of the anemia's etiology and ultimately to correct it. Thus, in future iterations of this alert, it is unlikely that only patients scheduled for high blood loss surgery would be targeted as investigating the etiology of the anemia in someone with a low Hb concentration and correcting it are important interventions in their own right. In more than half of the cases when an alert was sent, no evidence of any intervention to investigate or correct the anemia was found. In only three cases was a novel treatment for the anemia instigated after the alert was sent.

The management of anemia is complex and can involve complex diagnostic testing, different treatment modalities, and co-ordination with multiple specialists. The limited response to the alerts in this study suggests that surgeons and physicians require more education about the potential adverse effects of operating on anemic patients. Even patients scheduled for low blood loss surgery would probably benefit from anemia correction as it is a risk factor for many other medical conditions. It is hypothesized that if a greater appreciation of the potential negative consequences of peri-operative anemia was had, more interventions to correct the anemia would have occurred. It is also possible that the wording or method of transmission of the alerts needs to be revised; an email alert is only effective if the email account to which it is sent is checked regularly, and if the alert does not end up in a ‘junk mail’ folder or worse yet, gets deleted immediately without being read. The low response rate to the post-study evaluation further suggests that electronic communications are not an effective way to interact with surgeons and physicians about their anemic patients. Future directions for this alert would therefore include mailing a hard copy of the alert to the designated individuals or sending the alert by facsimile. In addition, a standard anemia management protocol is being developed by the PBM committee of this multi-hospital system. The protocol will be incorporated into the alerts and will also be available on the local intra-net. It is hoped that by providing specific recommendations to the surgeons and PCPs who receive these alerts, more anemic patients will be treated after receipt of the alert.

Other electronic PBM alerts have been implemented at this institution. For example, when a physician attempts to order a blood product using the computerized physician order entry system for a routine indication (i.e. not an urgent massive bleed), an on screen alert is generated if the patient's antecedent laboratory value is not consistent with the institutional transfusion thresholds.Citation16–Citation18 For example, if a physician attempts to order an RBC unit on an intensive care unit patient with a Hb value >7.5 g/dl, an alert will appear informing them of the patient's most recent Hb value. The alert can be ‘heeded’ and the order canceled, or else the alert can be dismissed and the order placed. Unfortunately, these alerts are insufficient to eliminate all transfusions that are apparently not indicated. The same appears to be true of these pre-operative anemia alerts. To optimize the effectiveness of these anemia alerts, a comprehensive educational program should also be implemented. The educational program should include provider education about the risks of peri-operative anemia, as well as a straightforward anemia management protocol with access to specialist consultation when necessary.

The email addresses to which the alerts were sent were the recipients' institutional email addresses. These accounts were chosen because the alerts contained some private health information (PHI) on the recipients and so confidentiality was required. Perhaps asking the surgeon's designated recipients if they would prefer to receive these alerts at a different account will increase the intervention rate, although the means of transmitting PHI by email would need to be validated.

Although only 3 of 69 patients had a novel hematinic treatment started after the alert was sent, it was encouraging to note that a significant number of patients had already been started on some form of medical anemia management before the alert was sent. In fact, for almost half of the iron recipients (11 of 23) and 1 of 16 of the B12/folate recipients the initiation date for their therapy could not be determined; thus it is possible that the response rate to the alerts was higher than the three patients where the start time of their iron therapy closely coincided with the alert. It is also possible that among the 37 patients in whom no anemia therapy was identified, some may have actually received some treatment that was not documented in their medical records. Perhaps a telephone message was left by the physician's office instructing the patient to start taking over the counter hematinic therapies, and not recorded in the patient's electronic health records.

As immediate pre-operative Hb concentrations were not measured on the three patients who started iron therapy after the alert was sent, it is not possible to know if these patients actually benefitted from the alert by having a higher Hb value at the time of surgery. Since the mean length of time between the day the alert was sent and the day of surgery was only 15 days, it is unclear how much of a benefit in terms of a higher Hb value could have been obtained in such a short period of time by hematinic therapy alone. Perhaps IV iron supplementation and erythropoietin would have been helpful given this short interval between alert notification and surgery date. Further education of physicians and surgeons about the potential adverse consequences of pre-operative anemia should also focus on ensuring that their patient's pre-operative blood work is ordered with a sufficient lead time to allow for the medical management of the anemia before the day of surgery.

This pilot study of automated anemia alerts on pre-operative patients demonstrated a need for enhanced provider education on the need to correct pre-operative anemia, and has potentially highlighted several areas for improvement about the technical aspects of these alerts.

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

Disclaimer statements

Contributors AD and MKW collected data, wrote the manuscript, approved the final version. JW and DT were involved in designing the study and approval of the final version. MY has designed the study, collected data, wrote the manuscript, and approved the final version.

Funding None.

Conflicts of interest None.

Ethics approval This protocol was approved by the University of Pittsburgh Total Quality Council, a division of the Institutional Review Board.

References

- Karkouti K, Wijeysundera DN, Beattie WS, Reducing Bleeding in Cardiac Surgery I. Risk associated with preoperative anemia in cardiac surgery: a multicenter cohort study. Circulation 2008;117(4):478–84.

- Gupta PK, Sundaram A, Mactaggart JN, Johanning JM, Gupta H, Fang X, et al. Preoperative anemia is an independent predictor of postoperative mortality and adverse cardiac events in elderly patients undergoing elective vascular operations. Ann Surg. 2013;258(6):1096–102.

- Musallam KM, Tamim HM, Richards T, Spahn DR, Rosendaal FR, Habbal A, et al. Preoperative anaemia and postoperative outcomes in non-cardiac surgery: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet 2011;378(9800):1396–407.

- Saleh E, McClelland DB, Hay A, Semple D, Walsh TS. Prevalence of anaemia before major joint arthroplasty and the potential impact of preoperative investigation and correction on perioperative blood transfusions. Brit J Anaesth 2007;99(6):801–8.

- Dunne JR, Malone D, Tracy JK, Gannon C, Napolitano LM. Perioperative anemia: an independent risk factor for infection, mortality, and resource utilization in surgery. J Surg Res. 2002;102(2):237–44.

- Shokoohi A, Stanworth S, Mistry D, Lamb S, Staves J, Murphy MF. The risks of red cell transfusion for hip fracture surgery in the elderly. Vox Sang. 2012;103(3):223–30.

- Carson JL, Brooks MM, Abbott JD, Chaitman B, Kelsey SF, Triulzi DJ, et al. Liberal versus restrictive transfusion thresholds for patients with symptomatic coronary artery disease. Am Heart J. 2013;165(6):964–71 e1.

- Jans O, Jorgensen C, Kehlet H, Johansson PI. Role of preoperative anemia for risk of transfusion and postoperative morbidity in fast-track hip and knee arthroplasty. Transfusion 2014;54(3):717–26.

- Yazer MH, Waters JH. How do I implement a hospital-based blood management program? Transfusion 2012;52(8):1640–5.

- Carson JL, Terrin ML, Noveck H, Sanders DW, Chaitman BR, Rhoads GG, et al. Liberal or restrictive transfusion in high-risk patients after hip surgery. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(26):2453–62.

- Villanueva C, Colomo A, Bosch A, Concepcion M, Hernandez-Gea V, Aracil C, et al. Transfusion strategies for acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding. The New England journal of medicine. Res Support, Non-U.S. Gov't. 2013;368(1):11–21.

- Hajjar LA, Vincent JL, Galas FR, Nakamura RE, Silva CM, Santos MH, et al. Transfusion requirements after cardiac surgery: the TRACS randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2010;304(14):1559–67.

- Triulzi DJ, Assmann SF, Strauss RG, Ness PM, Hess JR, Kaufman RM, et al. The impact of platelet transfusion characteristics on posttransfusion platelet increments and clinical bleeding in patients with hypoproliferative thrombocytopenia. Blood 2012;119(23):5553–62.

- Slichter SJ, Kaufman RM, Assmann SF, McCullough J, Triulzi DJ, Strauss RG, et al. Dose of prophylactic platelet transfusions and prevention of hemorrhage. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(7):600–13.

- Nutritional anaemias. Report of a WHO scientific group. World Health Organization Technical Report Series. 1968;405:5–37.

- Collins RA, Triulzi DJ, Waters JH, Reddy V, Yazer MH. Evaluation of real-time clinical decision support systems for platelet and cryoprecipitate orders. Am J Clin Pathol. 2014;141(1):78–84.

- McWilliams B, Triulzi DJ, Waters JH, Alarcon LH, Reddy V, Yazer MH. Trends in RBC ordering and use after implementing adaptive alerts in the electronic computerized physician order entry system. Am J Clin Pathol. 2014;141(4):534–41.

- Yazer MH, Triulzi DJ, Reddy V, Waters JH. Effectiveness of a real-time clinical decision support system for computerized physician order entry of plasma orders. Transfusion 2013;53(12):3120–7.