Abstract

Background

Paroxysmal nocturnal haemoglobinuria (PNH) presents as two major entities: the classical form, predominantly haemolytic and a secondary type with marrow failure and resultant aplastic anaemia (AA-PNH). Currently, the treatment of choice of the haemolytic variant is eculizumab; however, the most frequent form of PNH in México is AA-PNH.

Patients and methods

Six consecutive AA-PNH patients with HLA-identical siblings were allografted in two institutions in México, employing a reduced-intensity conditioning regimen for stem cell transplantation (RIST) conducted on an outpatient basis.

Results

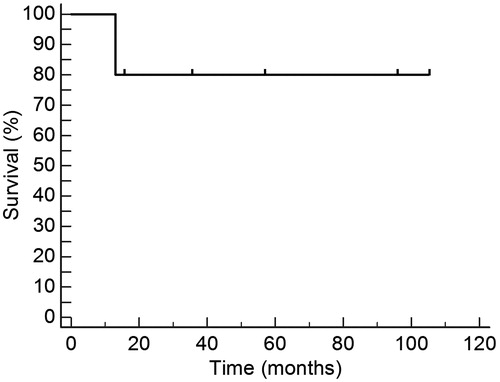

Median age of the patients was 37 years (range 25–48). The patients were given a median of 5.4 × 106/kg allogeneic CD34(+) cells, using 1–3 apheresis procedures. Median time to achieve above 0.5 × 109/l granulocytes was 21 days, whereas median time to achieve above 20 × 109/l platelets was 17 days. Five patients are alive for 330–3150 days (median 1437) after the allograft. The 3150-day overall survival is 83.3%, whereas median survival has not been reached, being above 3150 days.

Conclusion

We have shown that hypoplastic PNH patients can be allografted safely using RIST and that the long-term results are adequate, the cost–benefit ratio of this treatment being reasonable. Additional studies are needed to confirm the usefulness of RIST in the treatment of AA-PNH.

Introduction

Paroxysmal nocturnal haemoglobinuria (PNH) is recognised as a progressive disease of haematopoietic stem cells with acquired somatic mutations in the PIG-A gene located on Xp22.1 locus,Citation1–Citation6 which go through a non-malignant clonal expansionCitation1 that may in some cases be oligoclonal rather than monoclonal.Citation7 The progeny has an insufficient capability in the transfer of N-acetyl glucosamine to phosphatidyl inositol, a vital component of glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchor protein (GPI-AP).Citation1,Citation2,Citation5,Citation7,Citation8 PNH erythrocytes are deficient in decay accelerating factor (DAF/CD55) that inhibits the complement activation, and in the membrane inhibitor of reactive lysis (MIRL/CD59), which impairs complement cytolytic functions, thus generating extravascular and intravascular haemolysis, respectively.Citation2,Citation5,Citation8–Citation10 There are two major entities of PNH, the classical form, predominantly haemolytic, and a secondary type with marrow failure and resultant aplastic anaemia (AA-PNH).Citation11 In both forms, blood cells are deficient in CD55 and CD59.Citation12 The primary clinical manifestation is haemolysis with haemoglobinuria, which occurs in patients with the classical form; in those patients with AA-PNH, this can be absent due to a small PNH clonal cell size.Citation1,Citation2,Citation5 Certain variants of PNH seem to be more frequent in different populations; in Mexican mestizos, the cytopaenic variants comprise around 50% of all PNH cases.Citation12–Citation14

The only curative treatment for PNH patients is allogeneic stem cell transplantation,Citation5,Citation6,Citation11 Despite treatment with corticosteroids such as prednisone, the use of androgenic therapy, continuous iron replacements, the application of eculizumab as a humanised monoclonal antibody against activation of C5 in the alternative complement cascade and even splenectomy, many patients die within 5 years of diagnosis.Citation15–Citation17 Eculizumab has been shown to be useful only in the treatment of PNH patients with the haemolytic variant of the disease,Citation16 which is less common in México;Citation12–Citation14 it is an expensive drug, with an estimated price of around 400 000 USD per year per patient, it does not eradicate the PNH clones and it must be given throughout the patient's lifetime.Citation5,Citation11 On the other hand, the median cost of the first 100 days after an allogeneic reduced-intensity conditioning allogeneic stem cell transplantation (RIST) in México is 20 000 USD.Citation18–Citation20

We present here the results of RIST in six consecutive patients with AA-PNH in two different institutions in México, and discuss this therapeutic option in the current, modern and eculizumab era of the treatment of PNH.

Material and methods

Patients and donors

Consecutive patients with hypoplastic (less than 10% cellularity in bone marrow biopsy) forms of PNH, allografted in the Centro de Hematología y Medicina Interna de Puebla (Puebla, México) and in the Hospital Universitario de Nuevo León (Monterrey, México), were prospectively accrued in the study. shows some of the patient's salient features. Prior to 1997, the diagnosis of PNH relied on the abnormality of the classic PNH tests: Ham's test, haemolysis by inulin and haemolysis by sucrose; after 1997, the diagnosis was based on the expression of CD55 and CD59, tested by flow cytometry in red blood cells, granulocytes and platelets, whereas after 2012, the diagnosis relied on fluoresceinated aerolysin variant (FLAER)-based assays to detect granulocytes and monocytes lacking expression of GPI-linked structures.Citation12 All the patients had a Karnofsky score of 100% when the procedure was performed. The donor was an HLA-identical (6 of 6) sibling in all instances. Institutional review board approval and written consent was obtained from all the individuals. The Mexican method of reduced intensity conditioning was employed in all cases as previously described.Citation18–Citation20

Table 1. Salient features of the six PNH patients allografted from an HLA identical sibling

Apheresis product studies

Enumeration of the total white blood, mononuclear and CD34-positive cells was done by flow-cytometryCitation18–Citation20 in EPICS Elite ESP apparatus (Coulter Electronics, Hialeah, FL, USA) using the anti-CD34 monoclonal antibody HPCA-2 (Becton Dickinson, San José, CA, USA). No purging procedures were performed.

Molecular biology studies

In cases with a sex mismatch, a fluorescent in situ hybridisation technique to demonstrate the X and Y chromosomesCitation18–Citation20 was performed; in cases with ABO system mismatch a flow-cytometry-based approach was used, whereas polymorphic markers (short tandem repeats (STRs))Citation18–Citation20 were analysed in the absence of the previously mentioned mismatches. Molecular biology studies were done at diagnosis, at 30 days after the allograft and every 3–6 months thereafter. Overall survival (OS) was calculated according to Kaplan and Meier.Citation21

Results

Six PNH individuals with the cytopaenic variant of the disease were allografted; two were females (see ). One patient (number 3) had mild haemolysis associated. The diagnosis of PNH was performed in four of the six cases by means of the expression of CD55 and CD59 tested by flow cytometry in red blood cells, granulocytes and platelets; in two cases (patients 1 and 2) the diagnosis relied on the classical Ham's test, haemolysis by inulin and haemolysis by sucrose, whereas in one case, the diagnosis by flow cytometry was confirmed by FLAER-based assay to detect granulocytes and monocytes-lacking expression of GPI-linked structures.Citation12 Median age of the patients was 37 years (range 25–48 years). Median time from diagnosis to the allograft was 140 days (range 48–469 days). Patients received a median of 5.4 × 106/kg allogeneic CD34(+) cells, using one to three (median 1) apheresis procedures. Median time to achieve above 0.5 × 109/l granulocytes was 21 days, range 0–45, whereas median time to achieve above 20 × 109/l platelets was 17 days, range 0–45 days. Five patients are alive 330 to 3150 days (median 1437) after the RIST. The 3150-day OS is 83.3%, whereas median survival has not been reached, being above 3150 days (see ). Acute graft versus host disease (GVHD), defined as that occurring before day 100, presented in one patient (grade I) whereas two of the six (33%) have developed chronic GVHD. In one instance, the chronic GVHD was fatal despite intensive immunosuppression. One patient died 330 days after the RIST as a result of chronic GVHD; another patient (number 1) developed a donor-derived hairy cell leukaemia 1179 days after the allograft.Citation22 The 100-day mortality was 0%, whereas the transplant-related mortality was 16.6%; in all six patients the whole procedure was completed fully on an outpatient basis.

Discussion

With an estimated prevalence of 1.3 cases per million, PNH may occur at any age but is most frequently seen in adults between 30 and 50 years of age.Citation1,Citation2 There are data that suggest that PNH has been underestimatedCitation12 and that novel methods to identify PNH clones have resulted in increased recognition of the disease.Citation1,Citation2,Citation12 The treatment of PNH has also changed along time: prednisone, androgens, iron-replacement, splenectomy, eculizumab and stem cell transplantation have been used,Citation5,Citation6,Citation11,Citation12,Citation15–Citation17 the latter being the only curative treatment of the disease.Citation5,Citation6,Citation11

Economic aspects of the treatment of haematological diseases are critical, especially in developing countries. We have been particularly interested in the analysis of the cost–benefit aspects of the treatment of haematological diseases in México. Along this line, we have shown that stem cell transplantation, employing our ‘Mexican approach’, has a better cost–benefit ratio than treatment with novel drugs in chronic myelogenous leukaemiaCitation23,Citation24 and in multiple myeloma.Citation23,Citation25 Since the median cost of a stem cell allograft in our experience is 20 000 USD in the first 100 days,Citation18–Citation20,Citation23,Citation24 and the estimated price of the treatment of PNH with eculizumab is around 400 000 USD per year per patient,Citation5,Citation11 we can state that 20 patients with PNH could be allografted in our country with the amount of money employed in the treatment of a single patient for 1 year.

Eculizumab has been shown to be useful in the treatment of the haemolytic variants of PNH,Citation16 which are the less frequent in México.Citation12–Citation14 All the patients we are presenting here had the hypoplastic variant of the disease, which is, interestingly, the most frequent one in our country.Citation12–Citation14

Our results of allograting AA-PNH patients employing RIST are similar to our own results of allografting patients with severe aplastic anaemia with the same conditioning regimen.Citation26 The long-term survival of 83% of these hypoplastic PNH patients supports the election of this therapeutic approach, whereas the median cost of each procedure allows the practice of this treatment variant even in circumstances of economic disadvantage. The most challenging problem is still to identify those PNH patients who would benefit from allografting; the availability of a suitable donor is critical, since the results from using unrelated donors are worse than those employing identical siblings.Citation5,Citation6

In summary, we have shown that hypoplastic PNH patients can be allografted safely using RIST, that the long-term results are adequate and that the cost–benefit ratio of this treatment is reasonable. Additional studies are needed to confirm the usefulness of RIST in the treatment of the hypoplastic variants of PNH.

Disclaimer statements

Contributors AASC, NLM, LSGB and MAHR collected data and performed the analysis. DGA, GJRAD and GJRA wrote and reviewed the paper.

Funding None.

Conflicts of interest None.

Ethics approval The study was approved by the Ethics Committees of the Clinica Ruiz de Puebla as well as the Hospital Universitario de Nuevo León.

References

- Parker CJ, Omine M, Richards S, Nishimura J, Bessler M, Ware R, et al. Diagnosis and management of paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. Blood. 2005;106(12):3699–709.

- Parker CJ. Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. Curr Opin Hematol. 2012;19(3):141–8.

- Endo M, Beatty PG, Vreeke TM, Wittwer C, Singh SP, Parker CJ. Syngeneic bone marrow transplantation without conditioning in a patient with paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria: in vivo evidence that the mutant stem cells have a survival advantage. Blood. 1996;88(2):742–50.

- Ditschkowski M, Trenschel R, Kummer G, Elmaagacil AH, Beelen DW. Allogeneic CD34-enriched peripheral blood stem cell transplantation in a patient with paroxysmal nocturnal haemoglobinuria. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2003;32(6):633–5.

- Brodsky RA. Stem cell transplantation for paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. Haematologica. 2010;95(6):855–6.

- Santarone S, Bacigalupo A, Risitano AM, Tagliaferri E, Di Bartolomeo E, Iori AP, et al. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria: long-term results of a retrospective study on behalf of the Gruppo Italiano Midollo Osseo (GITMO). Haematologica. 2012;95(6):983–8.

- Risitano AM, Rotoli B. Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria: pathophysiology, natural history and treatment options in the era of biological agents. Biologics. 2008;2(2):205–22.

- Lee JW, Jang JH, Kim JS, Yoon SS, Lee JH, Kim YK, et al. Clinical signs and symptoms associated with increased risk for thrombosis in patients with paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria from a Korean Registry. Int J Hematol. 2013;97(6):749–57.

- Sutherland DR, Kuek N, Davidson J, Barth D, Chang H, Yeo E, et al. Diagnosing PNH with FLAER and multiparameter flow cytometry. Cytometry B Clin Cytom. 2007;72(3):167–77.

- Preis M, Lowrey CH. Laboratory test for paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. Am J Hematol. 2014;89(3):339–41.

- Peffault de Latour R, Schrezenmeier H, Bacigalupo A, Blaise D, de Souza CA, Vigouroux S, et al. Allogeneic stem cell transplantation in paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. Haematologica. 2012;97(11):1666–73.

- Ruiz-Argüelles GJ, Hernández-Reyes J, González-Ramírez MP, Martagón-Herrera NA, Rosales-Durón AD, Ruiz-Delgado GJ. Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria in México: a 30-year, single institution experience. Rev Invest Clin. 2014;66(1):12–6.

- Ruiz-Argüelles GJ, Morales-Aceves R, Labardini J, Kraus-Weisman A. Hemoglobinuria paroxística nocturna. Experiencia de 30 años en el Instituto Nacional de la Nutrición (México). Sangre (Barc). 1981;26:463–70.

- Góngora-Biachi R, González-Martinez P, Gonzalez-Llaven J, Delgado-Lamas J, Silva-Moreno M, Rico-Bazaldúa G. Clinical spectrum and prognostic factors in paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria in Mexico. Rev Invest Clin. 1994;46 (suppl 1):187.

- Kelly RJ, Hill A, Arnold LM, Brooksbank GL, Richards SJ, Cullen M, et al. Long-term treatment with eculizumab in paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria: sustained efficacy and improved survival. Blood. 2011;117(25):6786–92.

- de Latour RP, Mary JY, Salanoubat C, Terriou L, Etienne G, Mohty M, et al. Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria: natural history of disease subcategories. Blood. 2008;112(8):3099–106.

- Sharma V. Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria: pathogenesis, testing and diagnosis. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol. 2013;11(9):1–11.

- Gómez-Almaguer D, Ruiz-Argüelles GJ, Ruiz-Argüelles A, González-Llano O, Cantú OE, Hernández NE. Hematopoietic stem cell allografts using a non-myeloablative conditioning regimen can be safely performed on an outpatient basis. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2000;25:131–3.

- Ruiz-Delgado GJ, Ruiz-Argüelles GJ. A Mexican way to cope with stem cell transplantation. Hematology. 2012;17 (Suppl 1):195–7.

- Galo-Hooker E, Ruiz-Delgado GJ, Zamora-Ortiz G, Velázquez-Sánchez-de-Cima S, Ruiz-Argüelles GJ. In pursuit of the graft versus myeloma effect: a single institution experience. Hematology. 2013;18:89–92.

- Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparametric estimations from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc. 1958;53:457–63.

- Ruiz-Argüelles GJ, Ruiz-Delgado GJ, Calderón-Meza E, Ruiz-Argüelles A, Garcés-Eisele J. Donor-derived hairy cell leukemia. Leukemia Lymph. 2009;50:1712–4.

- Ruiz-Arguelles GJ. Whither the bone marrow transplant. Hematology. 2010;15:1–3.

- Ruiz-Argüelles GJ, Tarín-Arzaga LC, González-Carrillo ML, Gutiérrez-Riveroll KI, Rangel-Malo R, Gutiérrez-Aguirre CH, et al. Therapeutic choices in patients with Ph1 (+) chronic myelogenous leukemia living in México in the tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI) era: stem cell transplantation or TKI′s? Bone Marrow Transplant. 2008;42:23–8.

- López-Otero A, Ruiz-Delgado GJ, Ruiz-Argüelles GJ. A simplified method for stem cell autografting in multiple myeloma: a single institution experience. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2009;44:715–9.

- Gómez-Almaguer D, Vela-Ojeda J, Jaime-Pérez JC, Guitiérrez-Aguirre CH, Cantú-Rodríguez OG, Sobrevilla-Calvo P, et al. Allografting in patients with severe aplastic anemia using peripheral blood stem cells and a fludarabine-based conditoning regimen: the Mexican Experience. Am J Hematol. 2006;81:157–61.