Abstract

Objectives

We retrospectively compared the prophylactic effect of basiliximab and antithymocyte globulin (ATG) after haploidentical hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) in patients with leukemia.

Methods

Haploidentical HSCT using basiliximab for graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) prophylaxis in 10 patients with leukemia was retrospectively compared to ATG for GVHD prophylaxis in 24 patients.

Results

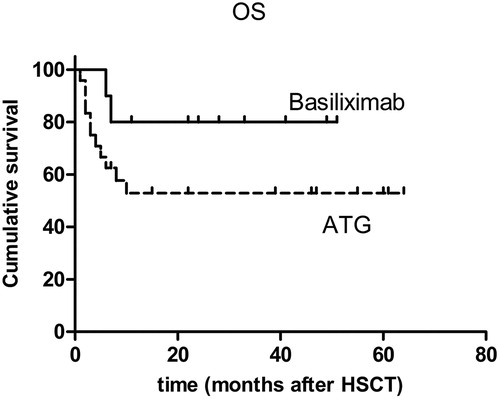

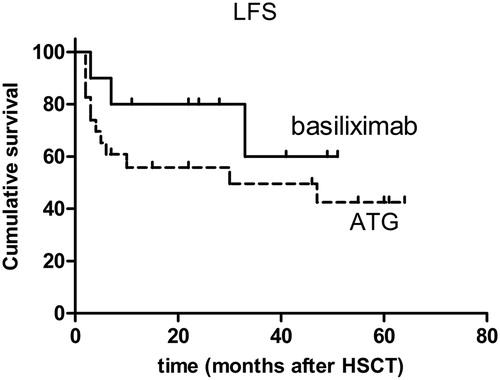

All the patients achieved neutrophil engraftment. One patient in the ATG group did not achieve platelet engraftment. The incidence of grade II–IV and grade III–IV acute GVHD was 30 and 20%, respectively, in the basiliximab group and 16.7 and 4.2%, respectively, in the ATG group (P > 0.05). Extensive cGVHD developed in 40 and 22.2% of patients in the basiliximab group and ATG group, respectively (P > 0.05). Basiliximab resulted in mild infection and a low incidence (10%) of infection-related mortality; ATG resulted in relative severe infection with 29.2% infection-related mortality (P > 0.05). During the follow-up period, 20% of the basiliximab group and 22.7% of the ATG group relapsed (P > 0.05). In the basiliximab group and the ATG group, the 3-year accumulative overall survival rate was, respectively, 80 and 52.5% and the 3-year leukemia-free survival, respectively, was 60 and 49.6% (P > 0.05).

Discussion

The incidences of grade II–IV and grade III–IV aGVHD in the basiliximab group were similar to those in halpoidentical HSCT containing ATG. Compared to the ATG group, the basiliximab group had a lower rate of transplantation-related mortality and better long-term survival, but without statistical significance.

Conclusion

The prophylactic regimen of basiliximab with haploidentical HSCT against GVHD seems safe and promising. More studies needed to verify this.

Introduction

Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) remains a curative treatment for patients with leukemia and results in long-term survival. However, the lack of human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-identical donors limits its application owing to engraftment failure and fatal severe graft-versus-host disease (GVHD). Because of the significant progress in allo-transplantation immunity and the introduction of highly effective immunosuppressive agents, haploidentical HSCT has been developed and has contributed to the increased likelihood of identifying available donors. Antithymocyte globulin (ATG), which is widely used as a potent immunosuppressive agent in haploidentical HSCT, is a polyclonal antibody directed against multiple lymphocyte antigens for depleting T lymphocytes, thereby significantly reducing GVHD.Citation1,Citation2 Despite its important role in GVHD prophylaxis, ATG harbors considerable adverse effects such as allergic reactions, impaired immune reconstitution, and possibly a high incidence of relapse because of its broad target population (e.g. T cells, B cells, natural killer cells, and monocytes).Citation3 Therefore, alternative immunosuppressive agents with less toxicity and better outcomes are needed.

Basiliximab is a chimeric murine–human monoclonal antibody that is directed against CD25, which is expressed on activated T lymphocytes. Basiliximab has been proved as a safe and an effective immunosuppressive agent to prevent engraftment failure in solid organ transplantation and represents an effective drug to treat acute steroid-refractory GVHD.Citation4 However, very few studies have addressed the prophylactic effect of basiliximab. In this study, a retrospective analysis assessed the effect of basiliximab versus ATG on engraftment, GVHD, transplantation-related infection, non-relapse mortality and survival, and adverse effects in patients with leukemia undergoing haploidentical HSCT.

Materials and methods

Baseline characteristics of the patients

Between March 2010 and May 2013, 10 patients with leukemia who underwent haploidentical HSCT received basiliximab. Between April 2008 and April 2013, 24 patients with leukemia who underwent haploidentical HSCT received ATG and the standard GVHD prophylaxis regimen at the Zhujiang Hospital of Southern Medical University (Guangzhou, China). All the patients had indications for allogeneic HSCT, but had no available matched sibling donors or matched alternative donors. The patients whose HLA typing was 3/6 matched with the donors did not receive the basiliximab regimen. The patients who met the aforementioned conditions were chosen in succession. The male/female ratio was 8/2 in the basiliximab group and 15/9 in the ATG group. The median age was 34 years (range, 13–54 years) in the basiliximab group and 24 years (range, 4–49 years) in the ATG group. The leukemia subtypes were as follows: in the basiliximab group, acute myeloid leukemia (AML) (n = 2), acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) (n = 6), and chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) blast-crisis (n = 2); in the ATG group, AML (n = 10), ALL (n = 12), and CML (n = 2). In the basiliximab group, seven patients were in their first complete remission (CR1), and three were in the advanced stages. In the ATG group, 13 patients were in CR1, three were in CR2, one was in CR3, three were in non-remission (NR), three were in relapse, and one patient was in CML blast-crisis. The data of these patients were retrospectively collected and analyzed with the approval of the Institutional Review Board on Medical Ethics at Zhujiang Hospital of Southern Medical University (Guangzhou, China). All the patients have signed the informed consents.

HLA typing

All the patients in the basiliximab group were 4/6 matched with their donors, whereas eight patients were 3/6 matched, 12 patients were 4/6 matched, and four patients were 5/6 matched in the ATG group. The HLA typing results of recipients and donors were obtained from the transplantation laboratory of Zhujiang Hospital of Southern Medical University (Guangzhou, China) and contained serological data of HLA-A, HLA-B, and HLA-DRB1.

Conditioning regimen and supportive care

Patients in both groups received a conditioning regimen that included fludarabine, busulfan, and cyclophosphamide (Flu, 50 mg/day from day −8 to −4, BU, 3.2 mg/kg daily from day −8 to −5, Cy, 60 mg/kg daily from day −4 to −3) or included fludarabine, busulfan, cyclophosphamide, and cytarabine (Flu, 50 mg/day from day −9 to −5, Ara-C, 4 g/m2 daily, from day −9 to −8, BU, 3.2 mg/kg daily from day −7 to −5, Cy, 60 mg/kg daily from day −4 to −3). Phenytoin (100 mg) was administered orally three times daily to prevent epilepsy when busulfan was administered. Two weeks before transplantation, ganciclovir (5 mg/kg every12 hours daily) was administered to prevent cytomegalovirus (CMV) reactivation until day −3. The CMV viral load was monitored weekly by polymerase chain reaction within 100 days post-transplantation. CMV reactivation was defined by positive CMV deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) detection in two consecutive blood samples. Pre-emptive therapy with ganciclovir was administered intravenously when CMV reactivation was detected. Patients who were febrile with neutropenia were treated with broad-spectrum antibiotics. Itraconazole or voriconazole was used to prevent fungal infection during the neutropenic period. For 6 months after transplantation, oral aciclovir and itraconazole were administered to prevent viral infection and fungal infection, respectively. Invasive fungal disease (IFD) was diagnosed according to the criteria by the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer/Invasive Fungal Infections Cooperative Group and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Mycoses Study Group (EORTC/MSG) Consensus Group.Citation5

Collection of hematopoietic cells

Donors were primed with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (5–10 μg/kg daily) injected subcutaneously for five to six consecutive days. On the fifth and sixth days, peripheral hematopoietic cells were collected at a rate of 50 ml/min from a total blood volume of 10 l. The target mononuclear cells count was not less than 5 × 108 kg. Hematopoietic cells harvested from the donor were directly transfused into the recipient without additional treatment.

Evaluation of engraftment and chimerism

Neutrophil engraftment was defined as an absolute neutrophil count of 0.5 × 109 l or more for two consecutive days. Platelet engraftment was defined as 20 × 109 l or more for three consecutive days without transfusion. Chimerism was determined by at least two of the following methods: (1) DNA-based HLA typing, (2) polymerase chain reaction DNA fingerprinting of short-tandem repeats on recipient peripheral blood cells, and (3) chromosomal fluorescence in situ hybridization on recipient bone marrow cells.

GVHD prophylaxis

In the basiliximab group, patients were injected intravenously with basiliximab at a dose of 1 mg/kg on days 0 and 4. Patients in the ATG group were intravenously administered ATG (Genzyme Corporation, Boston, MA, USA) at a dose of 2.5 mg/kg daily from day −5 to day −2. For both groups Ciclosporin A (CSA) was administered from day −3, and the serum concentration was maintained between 150 and 250 ng/ml. CSA was tapered from the end of the third month after transplantation and withdrawn within 6 months in the absence of GVHD. Methotrexate was administered intravenously at a dose of 15 mg/m2 on day +1 and at 10 mg/m2 on days +3 and +5. Mycophenolate mofeil was administered twice daily at a dose of 0.5–0.75 mg from day +1 to day +30; it was discontinued gradually. Acute GVHD was assessed and graded according to the Seattle Criteria.Citation6 Chronic GVHD was defined by the standard criteria.Citation7

Statistical analysis

Evaluations were based on data by 7 July 2014. Demographic factors were summarized by percentage, median, and range value. The mean value of the two groups was compared using the independent-samples t-test. Categorical variables were compared using the Chi-squared test or Fisher exact test. The cumulative probabilities of overall survival (OS) and leukemia-free survival (LFS) were evaluated by the Kaplan–Meier method. Data were analyzed using SPSS 16.0.

Results

Engraftment

All recipients except one achieved complete donor chimerism by day 30 after HSCT. One patient in the ATG cohort died of a cerebral hemorrhage before platelet engraftment. Patients engrafted to an absolute neutrophil count exceeding 0.5 × 109 l at a median of 14 days (range, 11–20 days) in the basiliximab group and 13.5 days (range, 10–24 days) in the ATG group. The median time to platelet recovery was 15 days (range, 12–19 days) in the basiliximab group and 14 days (range, 7–24 days) in the ATG group. No significant difference existed between the two groups in the time to neutrophil engraftment (P > 0.05) or platelet engraftment (P > 0.05).

Adverse effect

Symptoms and signs were recorded during and after the administration of basiliximab. No adverse effect directly associated with infusion of basiliximab was observed in any patient. However, 91.7% patients experienced fever with or without shivering during the infusion of ATG.

Graft-versus-host disease

In the basiliximab cohort, aGVHD developed in seven (70%) patients, which included four (40%) patients with grade I aGVHD, one (10%) with grade II aGVHD, two (20%) with grade III aGVHD, and none (0%) with grade IV aGVHD. The symptoms of the one patient with grade II aGVHD may have been induced by withdrawal of the immunosuppressive agent because of relapse. Symptoms of aGVHD included rash in four patients (40%), diarrhea in two (20%), and nausea and vomiting in one (10%). No patient had an elevation in liver enzymes or bilirubin levels. All the patients with rash or an upper gastrointestinal tract lesion obtained complete relief using methylprednisolone. Intestinal tract lesions in two patients with grade III aGVHD were resistant to methylprednisolone treatment, but were responsive to basiliximab. One patient had a complete response after four doses of basiliximab. However, the other patient had only a partial response after four doses of basiliximab, but had a complete response with the addition of mesenchymal stem cells to the treatment. The median time to aGVHD onset was 31 days (range, 26–85 days). Among 24 patients in the ATG group, 11 had no aGVHD, nine had grade I aGVDH, three had grade II aGVHD, one had grade III aGVHD, and none had grade IV aGVHD. The incidence of grade II–IV was 16.7% and of grade III–IV was 4.2%. Among the 13 patients with aGVHD, 10 patients (76.9%) had a good response to methylprednisolone and three (23.1%) were refractory to glucocorticoid treatment; all the patients obtained relief after basiliximab treatment. The median time to aGVHD onset was 31 days (range, 12–72 days).

In the basiliximab group, six (60%) patients developed chronic GVHD: two (20%) had limited cGVHD and four (40%) had extensive cGVHD. The symptoms of cGVHD manifested as skin rashes, mouth ulcers, diarrhea, and liver lesions. The median time to cGVHD onset was 175 days (range, 193–548 days). All the patients with cGVHD, except for one patient, were responsive to treatment with suppressive agents. In the ATG group, 18 patients survived beyond 100 days. Of these, 10 patients developed cGVHD (six (33.3%) had limited cGVHD and four (22.2%) had extensive cGVHD). The median time to cGVHD onset was 128 days (range, 101–1082 days). One patient was refractory to immunosuppressive agents and died from extensive cGVHD and concomitant infection. All other patients experienced relief after treatment. There were no significant differences between basiliximab and ATG groups in grade II–IV aGVHD, grade III–IV aGVHD, limited cGVHD, and extensive cGVHD (P > 0.05).

Infection

Among patients receiving basiliximab after allogeneic stem cell transplantation, nine (90%) were diagnosed as having probable IFD. Eight of these were cured after treatment with antifungal antibiotics. However, one patient had uncontrollable extensive cGVHD and was later diagnosed as having pneumonia by the high-resolution chest computed tomography (CT), which showed several nodules and interstitial changes. The detection of CMV DNA was positive and he was suspected of having CMV pneumonia and probable IFD. He failed to obtain relief after treatment with broad-spectrum antifungal antibiotics and ganciclovir. He died of uncontrollable extensive cGVHD shortly after being diagnosed as having pneumonia. Four (40%) patients experienced reactivation of CMV. One patient developed CMV cystitis and one was suspected of having CMV pneumonia. All but one patient attained CMV DNA clearance after ganciclovir treatment. Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) DNA was detected after HSCT, but none had a positive result for EBV.

In the ATG group, 15 (62.5%) patients had probable IFD and one (4.2%) was diagnosed with proven IFD. Among these patients, IFD was cured or controlled in nine patients; however, seven (29.2%) failed to respond to broad-spectrum antifungal drugs and died. CMV reactivation occurred in 12 (53.1%) of 21 patients in whom CMV DNA was detected; five patients developed CMV-related cystitis and were cured by ganciclovir. No patient had CMV pneumonia. Twelve (53.1%) of 21 patients in whom EBV DNA was detected experienced EBV reactivation. No patient developed lymphocyte proliferative disease. There was no significant difference between the two groups in the incidence of probable IFD or reactivation of CMV (P > 0.05). However, the incidence of EBV reactivation was significantly lower in the basiliximab group than in the ATG group (P < 0.05).

Relapse

In the follow-up period, two (20%) patients in the basiliximab group relapsed on days +70 and +396, respectively. One patient with CML in blast-crisis phase had complete hematological remission at the time of HSCT; he had extramedullary relapse in the central neutral system on day +70, and bone marrow relapse shortly after the extramedullary relapse. He stopped treatment, then died of the relapse. The other patient had ALL at her first remission when she received HSCT and had extramedullary relapse within her breasts. She withdrew immunosuppressive agents and was alive with relapse at the last follow-up.

In the ATG group, there were 22 patients in a state of remission when obtaining hematopoietic reconstitution after HSCT. Five (22.7%) of patients relapsed in the follow-up period and all relapses occurred in the bone marrow at a median of +173 days (range, 64–1030 days). Three patients stopped further treatment after the relapse and finally died. One patient experienced remission again after chemotherapy and donor lymphocyte infusion. The other was alive with relapse. There was no significant difference between basiliximab and ATG groups in the relapse rate (P > 0.05).

Transplantation-related mortality and survival

In basiliximab group, only one (10%) patient died of transplantation-related mortality (TRM). The cause of death was extensive cGVHD and pneumonia. In the follow-up period at a median of 30.5 months (range, 11–52 months), eight (80%) patients survived, and seven (70%) of them were alive without relapse. In the ATG group, nine (37.5%) patients died of TRM; of these, six died of infection; one died of infection and concomitant uncontrolled GVHD; one died of a cerebral hemorrhage; and one died of acute renal failure. In a median of 39 months (range, 6–68 months), 11 (45.8%) patients survived without relapse. The accumulative OS rate for 3 years was 80% in the basiliximab group and 52.5% in the ATG group (P > 0.05) (). The accumulative LFS was 60% in the basiliximab group and 49.6% in the ATG group (P > 0.05) (). There was no significant difference between the basiliximab and ATG groups in TRM (P > 0.05).

Discussion

Basiliximab is a chimeric monoclonal antibody directed against CD25, which is primarily expressed on activated T lymphocytes. The addition of basiliximab to CSA and steroid at a fixed dose of 20 mg on days 1 and 4 is associated with similar prevention of acute rejection and incidence of graft loss but a smaller incidence of infection and infection-related mortality in standard-risk renal transplantation and heart transplantation, compared to ATG.Citation8–Citation10 Furthermore, compared to ATG, basiliximab has the advantage of lower overall cost.Citation11 With regard to HSCT, basiliximab has been widely used to treat refractory aGVHD and is associated with a satisfying response.Citation12,Citation13 However, the prophylactic use of basiliximab against GVHD has rarely been addressed. Several transplantation prophylactic regimens combining basiliximab and ATG and conventional immunosuppressive agents such as CSA, MMF, and MTX have resulted in a low incidence of GVHD but a high rate of infection and TRM.Citation14,Citation15 The use of basiliximab without ATG to prevent GVHD showed a promising incidence of GVHD and was reported only in a retrospective matched unrelated HSCT study.Citation16 However, the data on basiliximab used alone rather than in combination with ATG in haploidentical HSCT are lacking. Therefore, in this study the effect on GVHD by using basiliximab in combination with MMF, CSA, and MTX was evaluated in the setting of haploidentical HSCT.

Prophylactic regimens containing basiliximab without ATG against GVHD have only been reported by Fang et al.Citation16 in a matched unrelated HSCT study in which the rates of grade II–IV and grade III–IV aGVHD were 35.4 and 15.9%, respectively. Whether basiliximab alone as the main prophylactic agent against GVHD would have a similar result in the setting of haploidentical HSCT is unclear. We tested the regimen in 10 recipients of haploidentical HSCT. Considering that stronger immunosuppressive agents are usually needed in haploidentical HSCT than in matched unrelated HSCT, the dosage of basiliximab in this study was increased from a fixed dose of 20 mg–1 mg/kg for each dosage. Furthermore, in this study there was no patient in the basiliximab group whose HLA typing was 3/6 matched with donors which is usually related with severe GVHD. The results showed that the incidence of grade II–IV and grade III–IV aGVHD in the basiliximab group was 30 and 20%, respectively, which was similar to the incidence in the ATG group in this study and the incidence in haploidentical HSCT containing ATG reported by others.Citation17–Citation20 There may be three interpretations for the low incidence of GVHD in the basiliximab group: (1) fludarabine in the conditioning regimen may have strengthened immunosuppression; (2) the dose of basiliximab was higher in this study than in conventional use; and (3) there may not have been a 3/6 matched donor for haploidentical HSCT in the basiliximab group.

Infection is another fatal complication following allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Basiliximab resulted in a relatively high incidence of probable fungal infection in this study. The diagnosis of IFD was based on the criteria by EORTC/MSG. Patients diagnosed with probable IFD met the three requirements: (1) host factor as a recipient of allogeneic HSCT; (2) lower respiratory tract fungal disease represented as signs on CT; and (3) mycological criteria of positive result for serum β-D-glucan. It was difficult to obtain direct evidence for the presence of fungal elements or recovery by culture of a mold in sputum. In a retrospective study of 250 consecutive patients with acute leukemia who underwent haploidentical HSCT in a northern city in China, the accumulative incidence of opportunistic infections during a 3-year follow-up period was 49.1%.Citation17 However, our transplantation center is in a moist southern city in China where patients are more susceptible to fungal infection. Most patients in our center had a prior history of pulmonary IFD after completing several chemotherapeutic treatments at the time of HSCT. Therefore, the risk of recurrent IFD increased during long-term follow-up. Furthermore, long-term treatment with immunosuppressive agents for cGVHD is a risk factor for IFD,Citation21 which was higher in the basiliximab group than in the ATG group; this may partly account for the high incidence of IFD in the basiliximab group in this study. Despite the high risk of pulmonary IFD, most patients with IFD in the basiliximab group were cured after treatment, and the infection-related mortality was only 10%. The incidence of pulmonary IFD tended to be lower in the ATG group than in the basiliximab group; however, patients with IFD experienced more severe infection and had a poorer response to potent antifungal treatment, which resulted in a high incidence of infection-related mortality. Six of seven patients who succumbed to infection died within 6 months after HSCT in the ATG group. The interruption of ATG to immune system reconstitution may be associated with the high incidence of infection-related mortality.

Similar to the strategy of targeting activated T cells using basiliximab, the approach of post-transplant Cy has recently been used to deplete activated allogeneic T cells in vivo. Post-transplant Cy was initially developed for haploidentical HSCT after reduced-intensity conditioning. Luznik et al.Citation22 reported a phase 2 trial of haploidentical HSCT using post-transplant Cy. The trial was performed in Baltimore, MD and Seattle, WA and involved 68 patients. Cyclophosphamide (50 mg/kg daily) was administered on day +3 only or on days +3 and +4. The incidence of grade II–IV aGVHD and grade III–IV aGVHD was 34 and 6%, respectively. At 1 year, the cumulative incidence of TRM and relapse was 15 and 51%, respectively.Citation22 Several small studies have more recently extended the approach to myeloablative conditioning in haploidentical HSCT in which the use of post-transplant Cy resulted in a low incidence of severe aGVHD (7–20%), cGVHD (13–42%), and TRM (10–12%).Citation23,24 The outcome of our study using basiliximab for GVHD prophylaxis is in line with the results of the low incidence of GVHD and TRM from post-transplant Cy approach, which indicates that the strategy of targeting activated T cells after HSCT would be promising in the setting of haploidentical HSCT. However, the effect of basiliximab or post-transplant Cy for GVHD prophylaxis in haploidentical HSCT with myeloablative conditioning requires large sample studies for evaluation. In conclusion, the use of basiliximab in this study resulted in a cumulative 3-year OS of 80%, a LFS of 60%, and a low incidence of aGVHD and TRM. The GVHD prophylactic regimen of basiliximab seems to be safe and promising in the setting of haploidentical HSCT, which is worthy of more investigation, especially in prospective multicenter studies.

Disclaimer statements

Contributors All contributors played a role in the research work of our paper.

Funding This work is supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 81372249, No. 81300431), Foundation of the Ministry of Education of China for Returned Scholars, Research Fund for the Doctoral Program of Higher Education of The Ministry of national education China (Grant No. 20114433110012), the Project of Department of Education of Guangdong Province (Grant No. 2012KJCX0025), Key Project of Science and Technology of Guangzhou city (12C22121595) and Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province, China (Grant No. S2013040014449).

Conflicts of interest None.

Ethics approval Our paper has received ethical approval.

References

- Theurich S, Fischmann H, Chakupurakal G, Shimabukuro-Vornhagen A, Chemnitz JM, Holtick U, et al. Anti-thymocyte globulins for post-transplant graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis – a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2013;88:178–86.

- Kumar A, Mhaskar AR, Reljic T, Mhaskar RS, Kharfan-Dabaja MA, Anasetti C, et al. Antithymocyte globulin for acute graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis in patients undergoing allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation: a systemic review. Leukemia 2012;26:582–8.

- Bacigalupo A. Antilymphocyte/thymocyte globulin for graft versus host disease prophylaxis: efficacy and side effects. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2005;35:225–31.

- Sellar RS, Peggs KS. Recent progress in managing graft-versus-host disease and viral infections following allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Future Oncol. 2012;8:1549–65.

- De Pauw B, Walsh TJ, Donnelly JP, Stevens DA, Edwards JE, Calandra T, et al. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer/Invasive Fungal Infections Cooperative Group; National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Mycoses Study Group (EORTC/MSG) Consensus Group. Revised definitions of invasive fungal disease from the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer/Invasive Fungal Infections Cooperative Group and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Mycoses Study Group (EORTC/MSG) Consensus Group. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:1813–21.

- Przepiorka D, Weisdorf D, Martin P, Klingemann HG, Beatty P, Hows J, et al. 1994 Consensus Conference on acute GVHD grading. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1995;15:825–8.

- Shulman HM, Sullivan KM, Weiden PL, McDonald GB, Striker GE, Sale GE, et al. Chronic graft-versus-host syndrome in man: a long-term clinicopathologic study of 20 Seattle patients. Am J Med. 1980;69:204–17.

- Brennan DC, Daller JA, Lake KD, Cibrik D, Del Castillo D. Thymoglobulin induction study group. Rabbit antithymocyte globulin versus basiliximab in renal transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1967–77.

- Sageshima J, Ciancio G, Chen L, Burke GW III. Anti-interleukin-2 receptor antibodies-basiliximab and daclizumab – for the prevention of acute rejection in renal transplantation. Biologics 2009;3:319–36.

- Mattei MF, Redonnet M, Gandjbakhch I, Bandini AM, Billes A, Epailly E, et al. Lower risk of infectious deaths in cardiac transplant patients receiving basiliximab versus anti-thymocyte globulin as induction therapy. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2007;26:693–9.

- Yao G, Albon E, Adi Y, Milford D, Bayliss S, Ready A, et al. A systematic review and economic model of the clinical and cost-effectiveness of immunosuppressive therapy for renal transplantation in children. Health Technol Assess. 2006;10:1–157.

- Funke VA, de Medeiros CR, Setúbal DC, Ruiz J, Bitencourt MA, Bonfim CM, et al. Therapy for severe refractory acute graft-versus-host disease with basiliximab, a selective interleukin-2 receptor antagonist. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2006;37:961–5.

- Wang JZ, Liu KY, Xu LP, Liu DH, Han W, Chen H, et al. Basiliximab for the treatment of steroid-refractory acute graft-versus-host disease after unmanipulated HLA-mismatched/haploidentical hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2011;43:1928–33.

- Ji SQ, Chen HR, Han HM, Wang HX, Liu J, Zhu PY, et al. Anti-CD25 monoclonal antibody (basiliximab) for prevention of graft-versus-host disease after haploidentical bone marrow transplantation for hematological malignancies. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2005;36:349–54.

- Di Bartolomeo P, Santarone S, De Angelis G, Picardi A, Cudillo L, Cerretti R, et al. Haploidentical, unmanipulated, G-CSFprimed bone marrow transplantation for patients with high-risk hematologic malignancies. Blood 2013;121:849–57.

- Fang J, Hu C, Hong M, Wu Q, You Y, Zhong Z, et al. Prophylactic effects of interleukin-2 receptor antagonists against graft-versus-host disease following unrelated donor peripheral blood stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2012;18:754–62.

- Huang XJ, Liu DH, Liu KY, Xu LP, Chen H, Han W, et al. Treatment of acute leukemia with unmanipulated HLA mismatched/haploidentical blood and bone marrow transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2009;15:257–65.

- Lv M, Huang XJ. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in China: where we are and where to go. J Hematol Oncol. 2012;18(5):10.

- Anasetti C, Aversa F, Brunstein CG. Back to the future: mismatched unrelated donor, haploidentical related donor, or unrelated umbilical cord blood transplantation? Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2012;18:S161–5.

- Brunstein CG, Fuchs EJ, Carter SL, Karanes C, Costa LJ, Wu J, et al. Blood and marrow transplant clinical trials network. Alternative donor transplantation after reduced intensity conditioning: results of parallel phase 2 trials using partially HLA-mismatched related bone marrow or unrelated double umbilical cord blood grafts. Blood 2011;118:282–8.

- Liu Q, Lin R, Sun J, Xiao Y, Nie D, Zhang Y, et al. Antifungal agents for secondary prophylaxis based on response to initial antifungal therapy in allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients with prior pulmonary aspergillosis. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2014;20:1198–203.

- Luznik L, O'Donnell PV, Symons HJ, Chen AR, Leffell MS, Zahurak M, et al. HLA-haploidentical bone marrow transplantation for hematologic malignancies using nonmyeloablative conditioning and high-dose, posttransplantation cyclophosphamide. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2008;14:641–50.

- Symons H, Chen AR, Luznik L, Kasamon YL, Meade JB, Jones RJ, et al. Myeloablative haploidentical bone marrow transplantation using T-cell replete peripheral blood stem cells and myeloablative conditioning in patients with high risk hematologic malignancies who lack conventional donors is well tolerated and produces excellent relapse-free survival: results of a prospective phase II trial. Blood 2011;118:4151.

- Solomon SR, Sizemore CA, Sanacore M, Zhang X, Brown S, Holland HK, et al. Haploidentical transplantation using T-cell replete peripheral blood stem cells and myeloablative conditioning in patients with high-risk hematologic malignancies who lack conventional donors is well tolerated and produces excellent relapse-free survival: results of a prospective phase II trial. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2012;18:1859–66.