Abstract

Objective

Clinical trials have demonstrated improved outcomes for patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) treated with regimens containing rituximab, but variations in real-world treatment patterns and outcomes have not been studied. The objective of this study was to characterize real-world treatment patterns and outcomes in higher risk DLBCL patients.

Methods

Patients with an International Prognostic Index score (IPI) ≥3 who received initial rituximab-based therapy from 2005 to 2012 were identified via electronic medical record data from the International Oncology Network. Initial therapy, rates of complete response (CR), post-CR treatments, and outcomes were evaluated.

Results

Among 257 eligible patients, 75% achieved a CR: 77% (158/206) of patients receiving R-CHOP compared to 71% (36/51) of patients receiving initial therapies other than R-CHOP. Post-CR, 78% of the 158 patients receiving R-CHOP underwent active surveillance; 13% received maintenance rituximab-based treatment; and 6% received radiation therapy. Relapse rates among patients receiving maintenance rituximab, active surveillance, and radiation therapy were 28% (6/21), 19% (24/124), and 0%, (0/10), respectively (P = 0.08).

Discussion

This study found that active surveillance continues to be the most commonly utilized treatment regimen among DLBCL patients with an IPI score ≥3 achieving a CR on first-line R-CHOP. Other approaches aimed at increasing the time to relapse are being utilized as well, but the clinical benefit of these modalities is unclear.

Conclusion

Results of this study are consistent with the results from clinical trials and suggest the need for further evaluation of maintenance therapy options for patients at higher risk of relapse.

Introduction

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is the most common lymphoid malignancy in adults, occurring most often in older patients (median age at diagnosis is 66 years) and accounting for one-third of all non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) cases in the United States.Citation1,Citation2 Despite its aggressive nature, DLBCL responds well to treatment and is potentially curable, particularly in patients with limited or localized disease; the likelihood of cure is considerably lower for the two-thirds of patients who present with advanced disease.Citation1,Citation3 The estimated 5-year survival rate of patients with DLBCL spans a wide range from 45 to 82% with stage of disease, age, treatment, and other factors playing important roles in prognostic risk and survival.Citation1,Citation2,Citation4,Citation5 For patients who receive R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone) as first-line therapy, 4-year survival may range from 55 to 94%.Citation6

The most commonly used predictor of survival in patients diagnosed with DLBCL has historically been the International Prognostic Index (IPI).Citation3 Shipp et al.Citation5 originally classified patients based on five risk factors: age >60, serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) above the upper limit of normal, performance status (PS) >1, tumor stage >II, and extranodal involvement beyond one site. Patients were divided into risk cohorts based on the number of risk factors: low (0 or 1), low-intermediate (2), high-intermediate (3), or high (4 or 5); categories are associated with 5-year survival rates of 73, 51, 43, and 26%, respectively.Citation5 While survival has improved with the addition of rituximab to first-line therapy, patients who are at high risk based on the IPI scale continue to have a poorer prognosis with 3-year survival rates of 59% compared to 91% for patients at low risk.Citation7

Irrespective of risk, first-line treatment with a rituximab-based regimen is the established standard of care for patients diagnosed with DLBCL.Citation8 R-CHOP is currently the only first-line category 1 regimen for DLBCL recommended by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN).Citation8 In clinical trials, 76% of patients on R-CHOP as first-line therapy achieved a complete response (CR); this response was maintained with follow-up out to 10 years, where more than 40% of patients were alive and in their initial CR.Citation9–Citation11

Although the introduction of rituximab to first-line treatment regimens has greatly improved initial outcomes among DLBCL patients, outcomes after failure of R-CHOP induction chemotherapy have been shown to be dismal.Citation12 Thus, efforts to identify innovative approaches aimed at reducing the risk of relapse remain a priority.

These efforts have been met with mixed results and considerable debate. Despite evidence of benefit in follicular and mantle cell lymphomas,Citation13–Citation16 maintenance therapy with rituximab has not been shown to prolong survival in DLBCL after first-line treatment with rituximab.Citation17 Results of studies examining the effect of consolidative radiation therapy after a CR with first-line treatment regimens have been varied. A pre-rituximab-era study showed improved 5-year event-free survival (EFS) (82 vs. 55%; P < 0.001) and overall survival (OS) (87 vs. 66%; P < 0.01) in patients with bulky stage IV DLBCL who received maintenance radiation therapy after achieving a CR with first-line chemotherapy compared to patients who did not receive radiation therapy.Citation18 In the post-rituximab era, Held et al.Citation19 compared patients with bulky disease from the RICOVER study who received R-CHOP followed by maintenance radiotherapy to an amendment cohort of patients with bulky disease who received the same first-line therapy but no radiotherapy. The addition of radiotherapy significantly improved outcomes and eliminated bulky disease as a risk factor, particularly in a per-protocol analysis (3-year EFS of 80 vs. 54%; P = 0.001).Citation19 However, there was no statistically significant difference in rates of achieving a CR between patients with and without radiotherapy (70 vs. 57%; P = 0.121).Citation19 In contrast, a retrospective analysis found that consolidation radiation therapy after a CR with R-CHOP improved both progression-free survival (90 vs. 75%) and OS (91 vs. 83%) compared to R-CHOP alone,Citation4 irrespective of bulky disease status, though differences in baseline covariates make interpretation of these results difficult. Evidence suggests that the benefits of these and more controversial post-CR strategies may be most apparent in selected patients. For example, patients at high risk of recurrence may have improved outcomes with high-dose therapy and autologous stem cell transplantation.Citation8,Citation20 However, barring sufficient evidence, active surveillance remains the current recommendation for all patients achieving a CR with first-line therapy.

Although strategies for treating DLBCL patients with a higher risk of relapse are currently being explored in clinical trials, to the best of our knowledge, no studies have evaluated real-world treatment patterns and outcomes in this population. The goal of this study was to explore real-world treatment patterns and outcomes in patients with DLBCL at high risk of relapse, including both initial rituximab-based treatment and any subsequent treatment, in order to understand current practice and determine whether there is evidence for differential outcomes.

Materials and methods

Study design

This was a retrospective observational study of electronic medical record (EMR) data obtained from the International Oncology Network (ION). ION is a diversified, physician-services network whose EMR database contains data from 175 geographically dispersed providers who represent more than 25 large community-based practices across 12 states in the United States. The database contains standardized, oncology-specific EMR data on regimen plans and associated chemotherapy and supportive care administrations and clinical data on diagnoses, demographics, laboratory tests, stage, grade, vital signs, and PS. Information from standard fields was supplemented by a manual review of physician progress notes to refine and further characterize the target patient population. Documented vital status was supplemented with data from the social security death index.

Patient selection

Patients aged ≥18 years with a diagnosis of NHL (International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes 200.xx or 202.xx) and receiving rituximab-based therapy during the study period (01 January 2005–June 2012) were initially selected for study inclusion. DLBCL is inconsistently coded in databases, with 200.7 and 202.8 being the most common codes. Rituximab provides some additional specificity and narrows the population to patients receiving a standard-of-care treatment with curative intent. Physician progress notes were reviewed, and patients confirmed to have DLBCL and at high risk of recurrence, based on a calculated or stated IPI score of ≥3, were selected. The population at high risk was chosen, because these patients are most likely to experience a relapse. Patients were excluded from the primary analysis if they (1) received care for another primary cancer during treatment for DLBCL, (2) had DLBCL subtypes that had transformed from indolent to aggressive disease, or (3) did not have a documented response to first-line therapy. The nature of the response must have been specified in the progress notes by the treating physician.

Study cohorts and outcomes

Among patients achieving a CR, cohorts were defined based on post-CR treatment strategy: (1) active surveillance, (2) maintenance rituximab, (3) radiation therapy, (4) stem cell transplantation, or (5) combination therapy. Patients were then followed to the end of the study period or loss of follow-up and additional treatments or relapses were documented based on the progress notes.

Statistical analyses

Due to the exploratory nature of this study, analyses were descriptive or exploratory in nature. Descriptive analyses were performed through the tabular display of mean values, medians, ranges, and standard deviations of continuous variables of interest and frequency distributions for categorical variables. Comparisons were made between initial treatment (R-CHOP vs. non-R-CHOP), post-CR treatment cohort, and post-CR relapse. Analyses exploring differences in patient characteristics and IPI risk factors were measured using appropriate statistical tests (e.g., chi-square tests, nonparametric t-tests, Wilcoxon rank sum tests, and other nonparametric tests), and the significance of results was reported with P-values. Statistical significance was determined to be 0.05 or less. Due to the exploratory nature of these analyses, no adjustments were made for multiple comparisons.

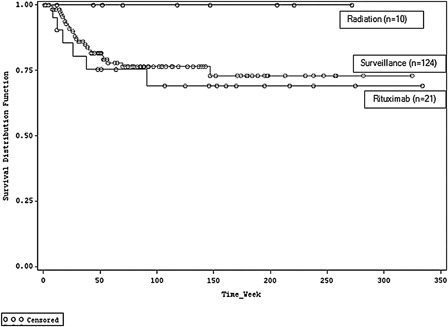

The characteristics of patients who relapsed and those who did not relapse were compared using a logistic regression. Time to relapse was measured as the average number of days from the CR date to the relapse date. Kaplan–Meier curves were produced for each post-CR treatment cohort. A Cox proportional hazards model was used to assess statistical differences between post-CR treatment strategies. All analyses were conducted using SAS® version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Patient selection and baseline patient characteristics

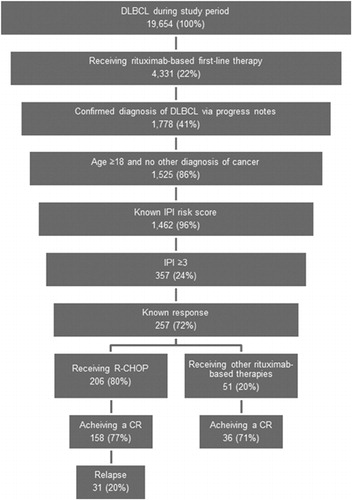

There were 19 654 patients identified with ICD-9-CM codes of either 200 or 202 during the study period, of whom 1462 had a confirmed diagnosis of DLBCL, rituximab-based first-line therapy, documented IPI risk score and who were 18 years of age or older. Approximately one-quarter of these patients (n = 357) had an IPI score ≥3. Overall, 257 patients had sufficient information to ascertain whether they had achieved a CR. shows the patient attrition waterfall.

Figure 1. Key: CR – complete response; DLBCL – diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; IPI – International Prognostic Index; R-CHOP – rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone.

Of the 257 DLBCL patients with an IPI score ≥3 who received rituximab in the first line of therapy and had documentation of tumor response, 80% (n = 206) were treated with R-CHOP. The most common alternatives were R-COP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and prednisone; 6%), R-monotherapy (5%), and R-CNOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, mitoxantrone, vincristine, and prednisone; 2%). These alternatives were mostly given to patients who were older, with an average age of 77 (vs. 69 for patients receiving R-CHOP). Patients receiving other therapies also tended to have more comorbidities than those receiving R-CHOP. The baseline characteristics for these groups are displayed in .

Table 1. Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics by post-CR treatment cohort

Among the 257 patients, 75% (n = 194) achieved a CR: 77% (n = 158) of the 206 patients with a documented response to R-CHOP compared to 71% (n = 36) of the 51 patients who received initial therapies other than R-CHOP. This difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.36).

Relapse rates and post-CR strategies

Overall, 38/194 (20%) patients with a CR subsequently relapsed, including 31/158 (20%) patients who received R-CHOP. Exploratory modeling failed to reveal significant baseline differences between those patients who relapse and those who do not, with the exception of gender difference (i.e., females were less likely to relapse then males) (odds ratio 0.234; 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.079, 0.693).

Due to the small number of patients receiving each of the alternative treatments and heterogeneity of the cohorts, a post-hoc decision was made to examine post-CR treatment strategies and outcomes in the subsample of patients receiving R-CHOP, which was the most widely used and currently the only first-line category 1 regimen for DLBCL (n = 206). For the 158 of these patients who achieved a CR, patients received a median of 6 cycles of R-CHOP therapy, with 122 receiving 6 or more cycles. There was no significant difference in likelihood of relapse between these patients and those not receiving 6 cycles (21 vs. 14% relapse; P = 0.47).

Of the 158 patients receiving R-CHOP who achieved a CR, 13% (n = 21) received rituximab maintenance therapy, 6% (n = 10) received radiation therapy, and 2% (n = 3) received other therapies or combinations of therapies. Of the remaining 78% (n = 124) of patients who did not receive any maintenance therapy, 78 had active surveillance indicated in their notes, while the remaining 46 had no specific notes regarding post-CR strategy but had no evidence of any additional active treatment. Out of the 78 patients with information about this post-CR strategy, 21% (n = 16) relapsed, while 33% (n = 15) of the 46 patients without explicit notes experienced a post-CR relapse. Post-hoc analyses revealed no significant differences in baseline variables, time to relapse, follow-up time, or CR assessment methods between those patients with and without notation of active surveillance. Thus, for the purposes of this study, all 124 with no evidence of receiving any additional active treatment were assumed to be undergoing active surveillance.

Baseline characteristics and outcomes for the different post-CR treatment groups are presented in . Although there are no statistically significant differences across the groups, there are expected trends wherein the patients receiving radiation therapy are more likely to have reported evidence of bulky disease (60% of all patients in the cohort vs. 19% of patients in other cohorts). However, bulky disease was inconsistently reported in patient records, and this difference is likely to be significantly influenced by reporting bias. Patients receiving radiation therapy were also more likely to have evidence of lymphoma in other organs, although this was not statistically significant. Because they are required to have three risk factors to be part of this study, they appear to be somewhat less likely to have other factors (worse PS, age >60, and stage III/IV disease).

Table 2. Outcomes by post-CR treatment cohort

Comparisons of post-CR therapies were challenging due to small sample sizes and differences in baseline populations. Relapse rates among patients receiving maintenance rituximab, active surveillance, and radiation therapy were 29% (6/21), 19% (24/124), and 0% (0/10), respectively. Within 6 months of CR, 14% (n = 3) of patients receiving rituximab maintenance therapy and 9% (n = 11) of patients undergoing active surveillance relapsed (). Mean time to relapse was 224 and 245 days for patients receiving maintenance rituximab therapy and those undergoing active surveillance, respectively. Relapse timing across cohorts that highlights patient censoring is shown in . Results of the Cox proportional hazard model revealed no statistically significant difference in relapse rates between patients receiving rituximab vs. those undergoing active surveillance (hazard ratio: 1.219; 95% CI: 0.438, 3.395).

Discussion

In this real-world retrospective analysis, patients with DLBCL and an IPI score ≥3 were followed to ascertain treatment patterns and outcomes. Generally, outcomes appeared consistent with evidence from prospective clinical trials with regard to both treatment patterns and therapeutic outcomes. Most patients received first-line therapy with R-CHOP. There was no statistically significant difference in CR rates between patients receiving R-CHOP (77%) and those receiving other rituximab-based regimens (71%). Due to the methods used to identify patients for this study, we were not able to compare these results to patients who did not initiate treatment with rituximab-based therapy, but this is expected to be a small proportion of those initiating therapy in the USA based on current NCCN treatment guidelines. Similar to our study, Coiffier et al.Citation9 reported that about 76% of patients initiating therapy with R-CHOP achieved a CR in the GELA (Groupe d'Etudes des Lymphomes de l'Adulte) trial, where patients were slightly healthier than this population based on baseline IPI risk factors. Thus, real-world effectiveness of R-CHOP appears to be consistent with efficacy levels seen in the clinical trial setting for patients with DLBCL at higher risk of relapse.

Of patients who had a CR, 20% of those who initiated with R-CHOP therapy subsequently relapsed. The majority (78%) of R-CHOP patients underwent active surveillance after their CR, which is the treatment currently recommended in NCCN guidelines.Citation8 A small subset of 13% received maintenance rituximab despite the lack of clear evidence for its benefit.Citation17 Only 6% of patients received consolidative radiation therapy, which has shown mixed results.Citation4,Citation19,Citation21 Patients who received radiation therapy had incomplete records with regard to bulky disease: 6/10 (60%) patients receiving radiation had bulky disease (the remaining four had unknown status), while 25/124 (20%) undergoing active surveillance and 2/21 (10%) patients receiving maintenance rituximab had bulky disease (the remaining had unknown status). Therefore, it is impossible to explore bulky disease as a factor in the choice to treat patients with post-CR radiation therapy in this analysis. Further research is needed to better understand the effect of bulky disease on the outcome of radiation or other maintenance therapy and risk of relapse.

This real-world study has a number of limitations. First, our assessment was descriptive in nature; therefore, results should be interpreted within this limited context. The ION EMR data, while very informative and wide-reaching, were limited to the content provided in progress notes for key study outcomes. In addition, ION data are confined to US-specific practice settings and may not be applicable to other regions. Our study inclusion criteria focused on patients with high-risk scores (IPI ≥ 3); thus, patients with low-risk scores (IPI ≤ 2) were not accounted for and may have provided helpful context around treatment patterns for DLBCL. A larger sample size of patients receiving rituximab-containing first-line regimens, along with statistical inference testing across multiple comparisons, would be needed to make any definitive conclusions regarding real-world treatment outcomes. Consistent long-term follow-up would further contribute to understanding current treatment patterns in this difficult-to-treat population with DLBCL. It is unclear how censoring and loss to follow-up may have affected this study, though patients who relapse are probably more likely to maintain contact with their physician in a real-world setting.

Conclusion

This study provides important baseline data regarding treatment patterns and outcomes in patients with DLBCL at higher risk of relapse. Real-world outcomes were consistent with clinical trial data, but sample size precluded detailed analysis of outcomes. While this study found that active surveillance continues to be the most commonly utilized treatment regimen among DLBCL patients with an IPI score ≥3 achieving a CR on first-line R-CHOP, other approaches aimed at increasing the time to relapse are being utilized as well. Relapse outcomes were consistent among treated groups, with or without additional post-CR therapy. Future research in this setting with a more robust DLBCL patient population in a controlled study is warranted.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Stephen Able of Eli Lilly and Company for his assistance with this study.

Disclaimer statements

Contributors AML, LMH, DSM, LL, ME and DS-M contributed to the conception and design of this study; LMH, DSM, LL, ME, EF and DS-M contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data; DSM, LL, ME and DS-M contributed to the drafting of this manuscript, and all authors critically reviewed the manuscript.

Funding This study was funded by Eli Lilly and Company. DM, LL, AL, and LH are all employees and shareholders of Eli Lilly and Company. ME and EF work for Xcenda, a company that received funding from Eli Lilly for its role in the development on this study. DS worked for Xcenda at the time of this study.

Conflicts of interest None.

Ethics approval This paper conforms to the guidelines issued by the Declaration of Helsinki. The study has been reviewed by the chair and by a member of the Liberty IRB administrative staff pursuant to the regulation of 45 CFR Part 46 concerning Institutional Review Boards.

References

- American Cancer Society [Internet]. Non-Hodgkin lymphoma. [cited 2013 Oct 16]: Available from: http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/cid/documents/webcontent/003126-pdf.pdf.

- Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, Garshell J, Neyman N, Altekruse SF, et al., (editors) [Internet]. SEER cancer statistics review, 1975–2010, Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute. Available from: http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2010/, based on November 2012 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site, April 2013.

- Martelli M, Ferreri AJ, Agostinelli C, Di Rocco A, Pfreundschuh M, Pileri SA. [Internet]. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. [cited 2013 Jan 30]. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.critrevonc.2012.12. 009.

- Phan J, Mazloom A, Medeiros LJ, Zreik TG, Wogan C, Shihadeh F, et al. Benefit of consolidative radiation therapy in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with R-CHOP chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4170–6.

- Shipp MA, Harrington DP, Anderson JR, Armitage JO, Bonadonna G, Brittinger G, et al. A predictive model of aggressive non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:987–94.

- Sehn LH, Berry B, Chhanabhai M, Fitzgerald C, Gill K, Hoskins P, et al. The revised International Prognostic Index (R-IPI) is a better predictor of outcome than the standard IPI for patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with R-CHOP. Blood 2007;109:1857–61.

- Ziepert M, Hasenclever D, Kuhnt E, Glass B, Schmitz N, Pfreundschuh M, et al. Standard International Prognostic Index remains a valid predictor of outcome for patients with aggressive CD20 + B-cell lymphoma in the rituximab era. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:2373–80.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) [Internet]. Practice guidelines in oncology non-Hodgkin's lymphomas. Version 2.2013 [cited 2013 Oct 10]. Available from: http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/PDF/nhl.pdf.

- Coiffier B, Lepage E, Briere J, Herbrecht R, Tilly H, Bouabdallah R, et al. CHOP chemotherapy plus rituximab compared with CHOP alone in elderly patients with diffuse large-B-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:235–42.

- Feugier P, Van Hoof A, Sebban C, Solal-Celigny P, Bouabdallah R, Fermé C, et al. Long-term results of the R-CHOP study in the treatment of elderly patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: a study by the Groupe d'Etude des Lymphomes de l'Adulte. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:4117–26.

- Coiffier B, Thieblemont C, Van Den Neste E, Lepeu G, Plantier I, Castaigne S, et al. Long-term outcome of patients in the LNH-98.5 trial, the first randomized study comparing rituximab-CHOP to standard CHOP chemotherapy in DLBCL patients: a study by the Groupe d'Etudes des Lymphomes de l'Adulte. Blood 2010;116:2040–5.

- El Gnaoui T, Dupuis J, Belhadj K, Jais JP, Rahmouni A, Copie-Bergman C, et al. Rituximab, gemcitabine and oxaliplatin: an effective salvage regimen for patients with relapsed or refractory B-cell lymphoma not candidates for high-dose therapy. Ann Oncol. 2007;18:1363–8.

- Ghielmini M, Schmitz SF, Cogliatti SB, Pichert G, Hummerjohann J, Waltzer U, et al. Prolonged treatment with rituximab in patients with follicular lymphoma significantly increases event-free survival and response duration compared with the standard weekly ×4 schedule. Blood 2004;103:4416–23.

- Hainsworth JD, Litchy S, Burris HA III, Scullin DC Jr, Corso SW, Yardley DA, et al. Rituximab as first-line and maintenance therapy for patients with indolent non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:4261–7.

- Hainsworth JD, Litchy S, Shaffer DW, Lackey VL, Grimaldi M, Greco FA. Maximizing therapeutic benefit of rituximab: maintenance therapy versus re-treatment at progression in patients with indolent non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: a randomised phase II trial of the Minnie Pearl Cancer Research Network. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:1088–95.

- Forstpointner R, Unterhalt M, Dreyling M, Böck HP, Repp R, Wandt H, et al. Maintenance therapy with rituximab leads to a significant prolongation of response duration after salvage therapy with a combination of rituximab, fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and mitoxantrone (R-FCM) in patients with recurring and refractory follicular and mantle cell lymphomas: results of a prospective randomized study of the German Low Grade Lymphoma Study Group (GLSG). Blood 2006;108:4003–8.

- Habermann TM, Weller EA, Morrison VA, Gascoyne RD, Cassileth PA, Cohn JB, et al. Rituximab-CHOP versus R-CHOP alone or with maintenance rituximab in older patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3121–7.

- Avilés A, Neri N, Delgado S, Pérez F, Nambo MJ, Cleto S, et al. Residual disease after chemotherapy in aggressive malignant lymphoma: the role of radiotherapy. Med Oncol. 2005;22:383–7.

- Held G, Murawski N, Ziepert M, Fleckenstein J, Pöschel V, Zwick C, et al. Role of radiotherapy to bulky disease in elderly patients with aggressive B-cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:1112–8.

- Stiff PJ, Unger JM, Cook JR, Constine LS, Couban S, Stewart DA, et al. Autologous transplantation as consolidation for aggressive non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1681–90.

- Pfreundschuh M. Radiotherapy in the rituximab era: still a place? Hematol Meeting Rep. 2009;3:47–8.