Abstract

Objectives

Mature lymphoid neoplasms presenting with ‘prominent splenomegaly without significant lymphadenopathy’ are uncommon and pose unique diagnostic challenges as compared to those associated with lymphadenopathy. Their descriptions in the literature are largely limited to a few case series. We analyzed the spectrum of these lymphomas diagnosed by peripheral blood (PB) and/or bone marrow (BM) examination.

Methods

Over a period of 6 years, 75 patients were diagnosed with a lymphoma from PB/BM who had presented with predominant splenomegaly. Their clinical and laboratory records including PB and BM morphology; immunophenotyping using multi-parametric flow-cytometry and immunohistochemistry were reviewed. Wherever indicated, an extended panel of immunohistochemistry (IHC) was performed on BM biopsies for accurate sub-classification.

Results and Discussion

The commonest lymphomas were hairy cell leukemia (HCL) (32%) and splenic marginal zone lymphoma (SMZL) (24%). Others included diffuse large B cell lymphoma (8%), chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma (8%), mantle cell lymphoma (2.7%), and follicular lymphoma (1.3%), all of which usually presents with lymphadenopathy. SMZL was the commonest lymphoma among females and those with massive splenomegaly and lymphocytosis; while HCL was commonest in patients with pancytopenia. SMZL commonly presented with lymphocytosis; however, 22% of them also presented with pancytopenia.

Conclusion

The high diagnostic efficacy of PB and BM examination using flow-cytometry and immunohistochemistry in confirming and sub-classifying splenic lymphomas suggests that a thorough hematological evaluation should always precede a diagnostic splenectomy. Immunohistochemistry remains the best modality to identify sparse or intra-sinusoidal infiltration on BM biopsy and is particularly useful in patients with fibrotic marrows and pancytopenia.

Introduction

Mature lymphoid neoplasms presenting with ‘prominent splenomegaly without significant lymphadenopathy’ or predominant splenomegaly are uncommon compared to those associated with lymphadenopathy. They are also difficult to diagnose, as splenectomy remains the only option of getting a histological diagnosis in many situations, especially when peripheral blood (PB) or bone marrow (BM) are not overtly involved. The indolent course of many of these neoplasms can lead to an initial misdiagnosis of various other non-neoplastic conditions like infections (especially chronic malaria or visceral leishmaniasis especially in tropical countries), hemolytic anemia, autoimmune diseases, hepatic disease, etc.Citation1 These patients may be investigated due to cytopenias of various lineages. A BM examination performed as a part of work up can reveal the underlying lymphoproliferative disorder. While some lymphomas are relatively easy to detect on the bone marrow aspirate (BMA) and BM trephine biopsy; some others can pose diagnostic challenges.

The description of lymphomas presenting with predominant splenomegaly is largely limited to few case series in the literature.Citation2–Citation4 Lymphomas presenting with isolated splenic involvement with or without involvement of PB, BM or liver, in the absence of significant lymph node involvement are also collectively referred to as ‘splenic lymphomas’.Citation1 However, some authors were stricter in classification as they have excluded those cases with liver or BM involvement,Citation5 while some have included those cases with minimal BM and/or liver involvement.Citation6 The classification of lymphomas has evolved over the years, which limits the interpretation of the most of the descriptions of the spectrum of splenic lymphomas in literature. The available literature is therefore a mixture of cases diagnosed by splenectomy or BM examination. Some of the categories like splenic marginal zone lymphomas (SMZL) and hairy cell leukemias (HCL) are well known to present as predominant splenomegaly. However, most of other lymphomas commonly present with lymphadenopathy or extranodal masses with or without splenomegaly. Only much less commonly, do they create diagnostic difficulty when they present with predominant splenomegaly without significant lymphadenopathy.

In this paper, we analyze the spectrum of lymphomas presenting with predominant splenomegaly diagnosed by PB and/or BM examination based on World Health Organization (WHO) 2008 classification.Citation7 We discuss the morphological and immunophenotypic features as well as potential pitfalls in the diagnosis of these lymphoproliferative disorders from BMA and BM trephine biopsy.

Methods and materials

A retrospective study was performed over a period of six years; between January 2008 and December 2013 in the department of Hematology of a tertiary care Institute of northern India. Requisitions and reports of all BM examinations performed during this period were searched electronically for BMA and BM trephine biopsy showing infiltration by lymphoma using appropriate search terms. These records were further screened to identify patients with predominant splenomegaly and rule out the presence of significant lymphadenopathy. Patients who presented with significant lymphadenopathy at any site either on physical examination or on imaging were excluded from further evaluation. Those cases that satisfied the inclusion criteria (patients of any age, splenomegaly of any degree, absent or insignificant lymphadenopathy, infiltration of PB, BMA or BM trephine biopsy by mature lymphoid neoplasm) were further reviewed in detail. They were systematically analyzed for demographic profile, indication(s) for performing the BMA and BM trephine biopsy, spleen size, presence or absence of hepatomegaly, hemogram findings, BM examination findings, and immunophenotype by multi-parametric flow cytometry (FCM) or immunohistochemistry (IHC). Splenomegaly was classified into mild [<2 cms below left costal margin (LCM)], moderate [3–7 cms below LCM] and massive [≥8 cms below LCM].Citation8 The PB, BMA smears, BM trephine biopsy sections and immunophenotyping results were reviewed for uniform categorization of lymphomas according to the WHO 2008 classification.Citation7 Some of the cases had been previously assigned to a broad diagnostic category like B cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL-B) or T cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL-T) without further sub-classification during routine reporting. These cases were further sub-classified wherever possible by performing extended panel of IHC during this study.

BMA and BM trephine biopsy are routinely performed in our Institute by trained hematopathologists after informed consent by standard techniques using disposable needles.Citation9,Citation10 PB and BMA samples are collected in all cases for performing FCM. IHC was performed on BM trephine biopsy sections in cases where FCM could not be done. The antibodies used for FCM analysis in cases of suspected lymphomas were CD1a, CD2, CD3 (cytoplasmic and surface), CD4, CD5, CD7, CD8, CD10, CD11c, CD16, CD19, CD20, CD22, CD23, CD25, CD34, CD38, CD43, CD45, CD56, CD57, CD79a, CD103, CD123, FMC-7, kappa, lambda, light chains (surface and cytoplasmic), TCRαβ, TCRγδ, ZAP 70 (BD Biosciences, USA). The samples for FCM were acquired on BD FACS Canto II and analysis was done using BD FACS Diva software. The antibodies used for IHC were CD45, CD3, CD5, CD10, CD20, CD23, cyclin D1, CD72 (DBA.44), Bcl-2, Bcl-6 (DAKO, Denmark). After a thorough review of data available in each case, IHC was performed or repeated with extended panel, wherever required for better sub categorization.

Results

During the six-year study period, 11,769 BM examinations were performed on adult patients. These were done for diagnostic and staging purposes as well as for treatment evaluation. There were 75 patients diagnosed as having lymphoma from PB, BMA or BM trephine biopsy and who presented with predominant splenomegaly. Nearly 90% of our patients had moderate to massive splenomegaly. Middle aged and elderly males were commonly affected. Nineteen patients (25.3%) in our cohort were aged ≤40 years. The demographic and hematologic profile of the entire cohort is summarized in .

Table 1. Demographic and hematological profile of patients with prominent splenomegaly without lymphadenopathy

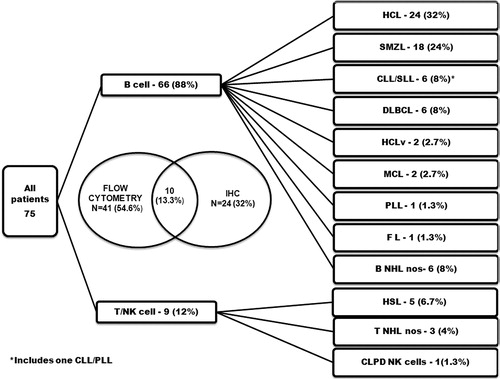

The diagnosis was made with the help of FCM in 41 patients (54.6%) and IHC in 24 (32%) patients (). Combination of FCM and IHC were utilized in making a diagnosis in 10 (13.3%) patients. FCM was attempted from PB in 8% (4/51) and from BMA in 92% (47/51), however IHC was utilized in case of a ‘dry tap’ or markedly diluted/scanty aspirate yielding low cellularity. In addition, IHC for cyclin D1 was done in all cases suspected of mantle cell lymphoma (MCL). IHC for CD72 (DBA.44) was performed in cases suspected of HCL in the absence of FCM. The diagnostic categories and their frequencies are summarized in .

Figure 1. The categories of mature lymphoid neoplasms, their frequencies and the diagnostic method utilized for their immunophenotyping in patients with prominent splenomegaly without lymphadenopathy.

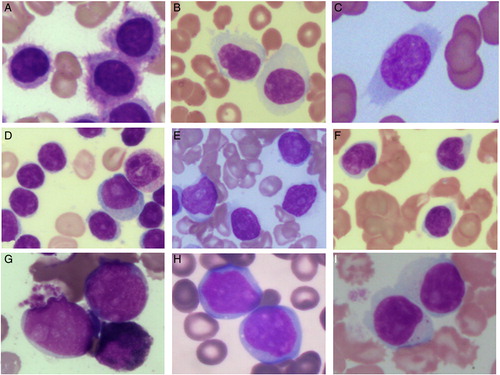

A majority of our patients had mature B cell lymphoma (88%); and HCL and SMZL were the commonest sub-types. Of the T cell lymphomas, γδ T cell hepatosplenic lymphomas (HSTL) were the most common subtypes. The clinical and hematological profile of various categories of lymphomas diagnosed in our study is summarized in . The morphological features are illustrated in and .

Figure 2. The morphological features of lymphoid cells in peripheral blood and/ or bone marrow aspirate (100x; May Grunwald Giemsa stain) (A) Hairy cells of HCL. (B) SMZL showing monocytoid lymphocytes. Short polar villi seen in one of them (C) Villous lymphocyte of SMZL (D) CLL showing small lymphocytes along with occasional prolymphocytes (E) B-cell PLL showing predominantly prolymphocytes (F) MCL showing lymphoid cells with irregular cleaved nucleus (G) Intravascular large B cell lymphoma showing blastoid appearing lymphoid cells (H) γδ HSTL showing medium to large sized lymphoid cells (I) CLPD NK cells showing large granular lymphocytes.

Figure 3. The morphology and salient immunohistochemistry findings of mature lymphoid neoplasms in bone marrow trephine biopsy. HCL showing typical ‘fried egg’ appearance (A) [Haematoxylin and eosin (H&E), 40x] and cytoplasmic positivity for CD72 (DBA.44) (B) [IHC, 40x]. MCL showing diffuse infiltration of bone marrow (C) [H&E, 40x] with nuclear positivity for cyclin D1 (D) [IHC, 40x]. SMZL showing nodular lymphoid infiltrate (E) [H&E, 10x] with intrasinusoidal and interstitial infiltrate highlighted by CD20 (F) [IHC, 20x]. DLBCL showing diffuse infiltration by large atypical lymphoid cells (G) [H&E, 40x] which are positive for CD20 (H) [IHC, 40x]. Intravascular large B cell lymphoma showing scattered atypical large cells (I) (H&E, 40x), the intrasinusoidal nature of which is highlighted by CD20 (J) [IHC, 40x]. Diffuse infiltrate of atypical large lymphoid cells with prominent eosinophilic nucleolus (K) [H&E, 40x], which are CD20+ CD5+ CD10− (not shown) and Cyclin D1− (L) [IHC, 40x] raising a differential diagnosis of cyclin D1 negative blastoid MCL and CD5+ DLBCL.

![Figure 3. The morphology and salient immunohistochemistry findings of mature lymphoid neoplasms in bone marrow trephine biopsy. HCL showing typical ‘fried egg’ appearance (A) [Haematoxylin and eosin (H&E), 40x] and cytoplasmic positivity for CD72 (DBA.44) (B) [IHC, 40x]. MCL showing diffuse infiltration of bone marrow (C) [H&E, 40x] with nuclear positivity for cyclin D1 (D) [IHC, 40x]. SMZL showing nodular lymphoid infiltrate (E) [H&E, 10x] with intrasinusoidal and interstitial infiltrate highlighted by CD20 (F) [IHC, 20x]. DLBCL showing diffuse infiltration by large atypical lymphoid cells (G) [H&E, 40x] which are positive for CD20 (H) [IHC, 40x]. Intravascular large B cell lymphoma showing scattered atypical large cells (I) (H&E, 40x), the intrasinusoidal nature of which is highlighted by CD20 (J) [IHC, 40x]. Diffuse infiltrate of atypical large lymphoid cells with prominent eosinophilic nucleolus (K) [H&E, 40x], which are CD20+ CD5+ CD10− (not shown) and Cyclin D1− (L) [IHC, 40x] raising a differential diagnosis of cyclin D1 negative blastoid MCL and CD5+ DLBCL.](/cms/asset/3f9eb6f6-fc31-40e4-a544-6bedec127743/yhem_a_11659347_f0003_b.jpg)

Table 2. Summary of clinical and hematological findings of mature lymphoid neoplasms diagnosed in patients with prominent splenomegaly without lymphadenopathy

Mature B cell neoplasms (n = 66)

HCL was the commonest and diagnosed in 24 patients. It also constituted 47% (9/19) of the patients with age of ≤40 years in our cohort. All cases showed variable number of ‘hairy cells’ in the BMA, characteristic morphology of BM trephine biopsy (A and 3A) and variable degrees of pericellular reticulin fibrosis. The immunophenotype (CD19+CD103+ CD25+CD11c+CD123+ in FCM or CD20+DBA.44+ in IHC) was characteristic of HCL in 23 patients. One patient showed characteristic morphological features in BMA and BM trephine biopsy, however IHC for CD72 (DBA.44) was negative. Seven patients of HCL did not have pancytopenia at presentation including three patients having normal leukocyte counts (4.6 to 10.4 × 109/L) and absolute lymphocytosis ().

The second commonest mature lymphoid neoplasm amongst our cohort was SMZL, constituting 24% (18/75) of all cases. Among females, SMZL was the most common diagnosis (10/28; 35.7%). Majority (72%) of these patients had massive splenomegaly. The diagnosis was made after exclusion of other lymphomas having characteristic immunophenotype and considering the morphology of neoplastic cells. Marked variation in absolute lymphocyte count was noted in this group (). PB and BMA showed lymphoid cells of varied morphology; large lymphocytes without nucleolus and monocytoid features; large lymphocytes with short polar villi; plasmacytoid lymphocytes; and occasional small cleaved lymphocytes (B, 2C, 3E, and 3F). BM trephine biopsy showed lymphoid nodules including paratrabecular ones along with interstitial and intrasinusoidal infiltrate. A diffuse infiltrate was seen in four patients. Background fibrosis of grade 2 to 3 (WHO) was noticed in three patients. The immunophenotype was CD19+CD5−CD23−CD10−CD103−CD123−CD25− (FCM) or CD20+CD5−CD10−DBA.44− (IHC) in 17 cases and CD20+CD5−CD10−DBA.44+ (IHC) in one case.

DLBCL was diagnosed in six patients and none of them revealed absolute lymphocytosis (). Patients with DLBCL had variable number of large blastoid cells in the BMA. Trephine biopsy showed interstitial, nodular, or diffuse infiltrate of large atypical lymphoid cells (CD20+CD5−CD10−/+Cyclin D1−) in five cases (G and H). One of the cases showed predominantly intrasinusoidal infiltrate of large atypical lymphoid cells (CD20+CD5−CD10−cyclinD1−) consistent with intravascular large B cell lymphoma (IVLBL) (G, 3I, and 3J). Background fibrosis of grade 2–3 (WHO) was noticed in two patients.

Six patients were diagnosed as chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma (CLL/SLL), which included three patients with (CLL) (ALC ≥ 5 × 109/L), two patients with SLL and one with chronic lymphocytic leukemia/prolymphocytic leukemia (CLL/PLL; prolymphocytes 20%). They showed typical morphology (D) and characteristic immunophenotype in FCM (Matutes scoreCitation11 4 or 5) or IHC. One case of SLL showed grade 2 (WHO) fibrosis.

In addition there were two patients of hairy cell leukemia variant (HCLv) diagnosed on the basis of morphological features and immunophenotype on FCM (CD20+CD5−CD23−CD10−CD25−CD103+CD11c+CD123−). Two patients were diagnosed to have mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) and one each had PLL and follicular lymphoma (FL) confirmed by characteristic immunophenotype.

Six cases of mature B-cell neoplasm could not be sub-typed (B-NHL, NOS). In five patients, BMA and BM trephine biopsy showed infiltration by atypical lymphoid cells, which were CD20+CD5+CD23−CD10−Cyclin D1−. In the absence of molecular studies, a further categorization was not possible. In one patient, there were paratrabecular nodules and interstitial infiltrate of lymphoid cells, which were CD20+ and CD3− (). Complete panel of IHC could not be performed due to lack of sufficient tissue for IHC.

Mature T cell neoplasms (n = 9)

HSTL was the commonest mature T cell neoplasm and was diagnosed in five patients. All five patients were <40 years of age with female predominance (). Light microscopy in all cases revealed variable number of medium sized to large lymphoid cells including blastoid ones in the PB and BMA (H). BM trephine biopsy showed predominantly intrasinusoidal infiltrate of neoplastic cells. The immunophenotype was CD3+γδTCR+CD56+/–CD57+/–; three cases were CD4−CD8− and two cases were CD4−CD8+.

A single patient showed persistent large granular lymphocytosis with immunophenotype consistent with chronic lymphoproliferative disorder of natural killer cells (CLPD NK cells). NHL-T NOS was made in three patients where the BM trephine biopsy showed interstitial or diffuse infiltration by CD3+ atypical cells. The expression of other markers including αβTCR or γδTCR could not be studied in these cases for further categorization due to lack of sufficient trephine biopsy material and loss of follow up of the patients ().

Discussion

‘Splenic lymphoma’ is a heterogeneous group including indolent to aggressive lymphomas and constitute <2% all lymphoid neoplasms; however is considered to be an underestimated problem. Nair et al. reports a prevalence of 1.04%.Citation1,Citation2,Citation4 Lymphomas, which constitute 36.5–57%, are the leading cause of ‘unexplained’ splenomegaly.Citation12–Citation14 They remain undiagnosed until the lymphoma is detected in PB, BM, diagnostic splenectomy specimen, or rarely in liver biopsy.

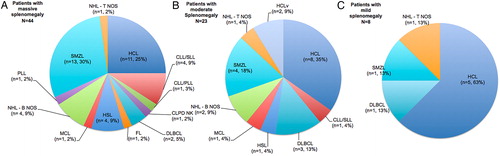

Majority of our patients (58.6%) presented with massive splenomegaly and the two most common diagnosis made in this group was SMZL (30%) and HCL (25%). Nearly 1/3rd of patients presented with moderate splenomegaly and HCL was the most common diagnosis in this group (35%) followed by SMZL (18%) and DLBCL (13%). Categories of splenic lymphomas diagnosed in patients presenting with massive, moderate and mild splenomegaly are summarized in .

Figure 4. The distribution of mature lymphoid neoplasms in patients presenting with massive (A), moderate (B), and mild (C) splenomegaly.

B-cell type mature lymphoid neoplasms were commonest in our cohort. There is a predominance of B NHLs in the literature as well.Citation2,Citation6 The frequency of occurrence of various lymphomas in patients with predominant splenomegaly is not very clear in the literature as the classifications of NHL have evolved over years. Most common NHLs in such patients were lymphoplasmacytoid NHL,Citation6 intermediate lymphocyte lymphoma,Citation3 and diffuse small lymphocytic lymphomaCitation15 in the older literature. Our results closely resemble the one reported by Pittaluga et al. in which the commonest lymphoproliferative disorder was HCL (14/39; 35.8%) followed by SMZL (9/39; 23%).Citation4 One third of our patients (n = 25, 33%) presented with ALC of >4000/μl, majority being SMZL (8/25, 32%). More than one third (n = 27, 36%) presented with pancytopenia with HCL (n = 17) comprising the majority of them ().

A diagnosis could be attained by FCM in majority of our cases (68%), however, IHC was needed for the diagnosis in rest of the patients. Cases diagnosed exclusively by IHC included SMZL (n = 7), diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL) (n = 6) including a case of IVLBL, HCL (n = 5), NHL-B not otherwise specified (NOS) (n = 3), NHL-T NOS (n = 2), and small lymphocytic lymphoma (SLL) (n = 1). IHC is especially useful in the diagnosis of intravascular DLBCL, which highlights the intrasinusoidal or intravascular pattern of lymphoma infiltration.

BM is usually involved in HCL, but may be patchy to be missed in small BM trephine biopsy. Literature also shows that leucocytosis is uncommon and the total leukocyte count (TLC) is usually <5 × 109 in 65% of the cases.Citation16 Three of our patients (12.5%) with HCL had lymphocytosis (ALC of 4.6–10.4 × 109/l), however, with normal leukocyte count (TLC of 6.7–11.9 × 109/l). HCL with very high TLC are rare in the literature.Citation17 CD72 (DBA.44) was positive in all but one case of HCL (4/5) evaluated by IHC. It is not completely specific for HCL and can be seen in SMZLCitation18 as seen in one of our cases. The study by Sherman et al. shows that a combination of CD72 (DBA.44) and tartarate resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) on IHC is useful to identify infiltration of HCL; however advocates the inclusion of other IHC markers like annexin-1 and cyclin D1 to improve the sensitivity and specificity. The IHC should be interpreted cautiously if used in isolation.Citation18

SMZL was more common in females (1:3) similar to a reported ratio of 1:1.8.Citation19 Absolute lymphocytosis was seen in 8/18 (44.4%) of our patients with SMZL. It is reported in up to 75% of the patients.Citation19 Morphological heterogeneity of neoplastic lymphocytes was most prominent in SMZL as described in the literature.Citation20 Intrasinusoidal infiltration is a feature of SMZL; hence subtle infiltration can be easily overlooked in the absence of IHC.Citation21,Citation22 Intrasinusoidal infiltration is not specific and can be seen in splenic diffuse red pulp small B cell lymphoma, HCLv, T-large granular lymphocyte leukemia, HSTL, intravascular DLBCL and rarely anaplastic large cell lymphoma.Citation1,Citation22 SMZL is known rarely to express CD5, however, a confident and accurate diagnosis is indeed difficult in the absence of molecular/cytogenetic studies.Citation20,Citation23

Primary DLBCL of spleen is uncommon compared to nodal DLBCL. It was seen in 8% of our patients compared to 10.2% in an earlier study.Citation4 One patient presented with bicytopenia and hepatosplenomegaly with exclusively intrasinusoidal invasion of CD20+CD5−CD10−Cyclin D1− large atypical lymphoid cells consistent with IVLBL reported earlier from Asian countries.Citation24,Citation25 DLBCL especially IVLBL, can have scattered interstitial or intrasinusoidal infiltrating atypical cells and typically requires IHC for a definite diagnosis.Citation26

CLL/SLL, MCL and FL usually present with lymphadenopathy with or without splenomegaly and is uncommon in patients presenting with predominant splenomegaly. CLL/SLL was seen in 8% of our patients compared to 2.6Citation4 and 3.6%Citation27 in earlier studies. Dighiero et al. reported a series of 23 patients with pure splenic forms of CLL.Citation28

There were only two patients (2.6%) with MCL in our study. Two previous studies have reported much higher frequencies of 43.7% (7/16) and 20.5% (8/39).Citation2,Citation4 However the diagnosis was not confirmed by immunophenotyping in one studyCitation2 while the other included CD5− and as t(11:14) negative cases.Citation4 Angelopoulou et al. reported seven patients of MCL who presented with predominant splenomegaly.Citation29 There was a single case in our study group with diffuse infiltration of BM trephine biopsy by atypical blastoid cells, which were CD20+CD5+CD10−CD23−cyclin D1− (K and L). The differential diagnosis of blastoid MCLCitation30 and CD5+ de novo DLBCL remained unsolved in the absence of cytogenetic studies. CD5+ DLBCL, which constitutes 5–10% of DLBCL usually, presents with prominent extranodal involvement and have a poorer outcome. Few primary hepatosplenic forms of CD5+ DLBCL are also described.Citation31,Citation32 Whether some of the cases of t(11:14) negative blastoid MCL represents recently described CD5+ de novo DLBCL is not clear.

HSTL were the commonest T cell lymphomas in our study diagnosed in five patients. Three of these cases were previously reported in a separate study from our institute.Citation33 BM involvement is seen in nearly 100% of patients with a prominent intrasinusoidal pattern of involvement especially in early stages and additional interstitial pattern of involvement in later stages.Citation34

Molecular or cytogenetic analysis is definitely required in the complete characterization of some of the lymphomas especially CD5+ NHL. Five of our cases with CD20+CD5+CD23−CD10−Cyclin D1− immunophenotype could not be further subtyped in the absence of molecular studies.

Our study is limited by lack of molecular studies; however, we have been sufficiently cautious while categorizing various lymphomas. The potential pitfalls while categorizing lynphomas in BMA and BM trephine biopsy include misdiagnosis of tiny nodular infiltrates of lymphoma cells especially SMZL as reactive lymphoid nodules or vice versa; non identification of scattered interstitial or intrasinusoidal infiltrate of neoplastic cells; missing a patchy infiltrate of neoplastic cells in small BM trephine biopsies and misclassification of various lymphomas in the absence of molecular studies. A careful study of PB and BM combined with FCM or IHC along with molecular studies in necessary cases helps to diagnose most of the cases of ‘splenic lymphoma’ necessitating the need of diagnostic splenectomy in only 5% of the cases.Citation1 In fact, the invasive procedure of choice in patients with ‘idiopathic splenomegaly’ should be BMA and BM trephine biopsy to confirm or rule out a hematologic cause as advised by O'Reilly based on a large study.Citation35 However, one important exception is the differentiation of SMZL from splenic diffuse red pulp lymphoma. Both of them have similar IHC profile. BM examination is not sufficient to distinguish between these two entities.Citation36

Conclusions

Mature B-lymphoid neoplasms formed majority of our patients presenting with ‘isolated splenomegaly’. HCL & SMZL together constituted 56% of all patients. HSTL (6.6%) was most common type of mature T-lymphoid neoplasm. Intrasinusoidal pattern of tumor infiltration is a common pattern of behavior of many of these lymphomas, which may easily be overlooked in H&E sections. IHC on trephine biopsy has to be frequently used in these patients. Our analysis highlights the role of PB and BM examination using FCM and IHC in the accurate sub-categorization of splenic lymphomas and we recommend its use as an investigation of choice over diagnostic splenectomy in these patients.

Disclaimer statements

Contributors SS: collection and analysis of data, helped to design the study, and wrote the paper. RD and MUSS: designed the study, performed and supervised the conduction of the study, analysis of data, and helped in writing of the paper. NV: supervised the conduction of the study and writing of manuscript, provided reagents for the performance of IHC and flow cytometry. JA, SN, PS and NK: involved in the interpretation of morphology, flow cytometry and IHC. Helped in preparation of manuscript. PM, GP, AK and SV: contributed patient data, provided valuable inputs for the preparation of manuscript.

Funding None.

Conflict of interest Authors declare that there are no conflict(s) of interest.

Ethics approval The research does not involve any experiments involving healthy volunteers, patients or animals requiring ethical clearance.

References

- Iannitto E, Tripodo C. How I diagnose and treat splenic lymphomas. Blood 2011;117:2585–95.

- Nair S, Shukla J, Chandy M. Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma presenting with prominent splenomegaly –clinicopathologic diversity in relationship to immunophenotype. Acta Oncol. 1997;36:725–27.

- Narang S, Wolf BC, Neiman RS. Malignant lymphoma presenting with prominent splenomegaly. A clinicopathologic study with special reference to intermediate cell lymphoma. Cancer 1985;55:1948–57.

- Pittaluga S, Verhoef G, Criel A, Wlodarska I, Dierlamm J, Mecucci C, et al. ‘Small’ B-cell non-Hodgkin's lymphomas with splenomegaly at presentation are either mantle cell lymphoma or marginal zone cell lymphoma. A study based on histology, cytology, immunohistochemistry, and cytogenetic analysis. Am J Surg Pathol. 1996;20:211–23.

- Dasgupta T, Coombes B, Brasfield RD. Primary malignant neoplasms of the spleen. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1965;120:947–60.

- Falk S, Stutte HJ. Primary malignant lymphomas of the spleen. A morphologic and immunohistochemical analysis of 17 cases. Cancer 1990;66:2612–19.

- Swerldlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, Jaffe ES, Pileri SA, Stein H, et al. (eds.) WHO classification of tumours of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues. 4th ed. Lyon: IARC; 2008. p. 9–13.

- Glynn M. Gastrointestinal system. In: Glynn M, Drake WM, (eds.). Hutchison's clinical methods – An integrated approach to clinical practice. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2012. pp. 217–48.

- Bain BJ. Bone marrow trephine biopsy. J Clin Pathol. 2001;54:737–42.

- Bain BJ. Bone marrow aspiration. J Clin Pathol. 2001;54:657–63.

- Matutes E, Owusu-Ankomah K, Morilla R, Garcia Marco J, Houlihan A, Que TH, et al. The immunological profile of B-cell disorders and proposal of a scoring system for the diagnosis of CLL. Leukemia 1994;8:1640–45.

- Kraus MD, Fleming MD, Vonderheide RH. The spleen as a diagnostic specimen: a review of 10 years’ experience at two tertiary care institutions. Cancer 2001;91:2001–09.

- Carr JA, Shurafa M, Velanovich V. Surgical indications in idiopathic splenomegaly. Arch Surg. 2002;137:64–8.

- Pottakkat B, Kashyap R, Kumar A, Sikora SS, Saxena R, Kapoor VK. Redefining the role of splenectomy in patients with idiopathic splenomegaly. ANZ J Surg. 2006;76;679–82.

- Kraemer BB, Osborne BM, Butler JJ. Primary splenic presentation of malignant lymphoma and related disorders. A study of 49 cases. Cancer 1984;54:1606–19.

- Jones G, Parry-Jones N, Wilkins B, Else M, Catovsky D. British Committee for Standards in Haematology. Revised guidelines for the diagnosis and management of hairy cell leukaemia and hairy cell leukaemia variant. Br J Haematol. 2012;156:186–95.

- Adley BP, Sun X, Shaw JM, Variakojis D. Hairy cell leukemia with marked lymphocytosis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2003;127:253–54.

- Sherman MJ, Hanson CA, Hoyer JD. An assessment of the usefulness of immunohistochemical stains in the diagnosis of hairy cell leukemia. Am J Clin Pathol. 2011;136:390–9.

- Franco V, Florena AM, Iannitto E. Splenic marginal zone lymphoma. Blood 2003;101:2464–72.

- Baseggio L, Traverse-Glehen A, Petinataud F, Callet-Bauchu E, Berger F, Ffrench M, et al. CD5 expression identifies a subset of splenic marginal zone lymphomas with higher lymphocytosis: a clinico-pathological, cytogenetic and molecular study of 24 cases. Haematologica 2010;95:604–12.

- Franco V, Florena AM, Campesi G. Intrasinusoidal bone marrow infiltration: a possible hallmark of splenic lymphoma. Histopathology 1996;29:571–75.

- Costes V, Duchayne E, Taib J, Delfour C, Rousset T, Baldet P, et al. Intrasinusoidal bone marrow infiltration: a common growth pattern for different lymphoma subtypes. Br J Haematol. 2002;119:916–22.

- Craig FE, Foon KA. Flow cytometric immunophenotyping for hematologic neoplasms. Blood 2008;111:3941–67.

- Ponzoni M, Ferreri AJ, Campo E, Facchetti F, Mazzucchelli L, Yoshino T, et al. Definition, diagnosis, and management of intravascular large B-cell lymphoma: proposals and perspectives from an international consensus meeting. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:3168–73.

- Shimada K, Kinoshita T, Naoe T, Nakamura S. Presentation and management of intravascular large B-cell lymphoma. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:895–902.

- Morice WG, Rodriguez FJ, Hoyer JD, Kurtin PJ. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma with distinctive patterns of splenic and bone marrow involvement: clinicopathologic features of two cases. Mod Pathol. 2005;18:495–502.

- Huhn D, von Schilling C, Wilhelm M, Ho AD, Hallek M, Kuse R, et al. Rituximab therapy of patients with B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood 2001;98:1326–31.

- Dighiero G, Charron D, Debre P, Le Porrier M, Vaugier G, Follezou JY, et al. Identification of a pure splenic form of chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Br J Haematol. 1979;41:169–76.

- Angelopoulou MK, Siakantariz MP, Vassilakopoulos TP, Kontopidou FN, Rassidakis GZ, Dimopoulou MN, et al. The splenic form of mantle cell lymphoma. Eur J Haematol. 2002;68:12–21.

- Viswanatha DS, Foucar K, Berry BR, Gascoyne RD, Evans HL, Leith CP. Blastic mantle cell leukemia: an unusual presentation of blastic mantle cell lymphoma. Mod Pathol. 2000;13:825–33.

- Zhang X, Sun M, Zhang L, Shao H. Primary hepatosplenic CD5-positive diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: a case report with literature review. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2013;6:985–89.

- Jain P, Fayad LE, Rosenwald A, Young KH, O'Brien S. Recent advances in de novo CD5+ diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Am J Hematol. 2013;88:798–802.

- Das R, Sachdeva MU, Malhotra P, Das A, Ahluwalia J, Bal A, et al. Diagnostic difficulties of pure intrasinusoidal bone marrow infiltration of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: a report of eight cases from India. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2011;41:1303–07.

- Falchook GS, Vega F, Dang NH, Samaniego F, Rodriguez MA, Champlin RE, et al. Hepatosplenic gamma-delta T-cell lymphoma: clinicopathological features and treatment. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:1080–85.

- O'Reilly RA. Splenomegaly in 2,505 patients at a large university medical center from 1913 to 1995. 1963 to 1995: 449 patients. West J Med. 1998;169:88–97.

- Ponzoni M, Kanellis G, Pouliou E, Baliakas P, Scarfò L, Ferreri AJ, et al. Bone marrow histopathology in the diagnostic evaluation of splenic marginal-zone and splenic diffuse red pulp small B-cell lymphoma: a reliable substitute for spleen histopathology? Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36:1609–18.