Abstract

This paper describes a very rare, hand-coloured, unusually large (over 13 m2) manuscript map of China about which, in addition to our own copy, only two more copies are known. The map shows the territory of the Ming Chinese empire (1368–1644) in the seventeenth century. It was prepared in 1691 by the famous Japanese Buddhist monk, Sōkaku (1639–1720). The paper highlights several historical and geographical details of the period and the most interesting history of the map.

Map of (China under) the Great Ming Dynasty, 大明省國, Da Ming Sheng Guo (Japanese reading: Dai Mei Sei Zu), copied from an unidentified map by the Japanese Buddhist monk Sōkaku, 宗覚, (1639–1720), (family name: 永田, Nagata), in the year, 元禄辛未, Genroku 4, 1691, fully hand-coloured manuscript, on native paper, 373×356 cm.

INTRODUCTION

Sōkaku was born in Kyōto. He studied music, medicine, various forms of military art and developed talent in his youth in all those disciplinesFootnote1. However, at the death of a parent, in 1662, at the age of 24 years, he decided to become a Buddhist monk and entered the Shoji In Temple, 諸寺院, in Kyōto. In 1679, he joined the Shingon (真言律宗, True Word) sect monastery of Kushūon In, 久修園院, of Esoteric BuddhismFootnote2. Deeply interested in world geography and Buddhist cosmology, after drawing the map of China, he made a map of India at approximately 1692 (entitled 五天竺国の図, Gotenjiku-Koku no Zu, manuscript) and a terrestrial globe, ca. 1708, (地球儀, Chikyūgi). Both have been preserved at the Kushūon In Temple at Hirakata City, 枚方市. After a life of total devotion to his function as principal of the monastery, he left this world in 1720.

The map is extremely rare, two or three manuscript copies have survivedFootnote3. The original map by a Chinese artist-cartographer, source of our manuscript map, has not been identified and is in all likelihood no longer extant.

Many old Chinese maps are only known from later reproductions. In the light of Chinese cartographic history, this is not surprising. Maps were made in China for commercial purposes, as well as on orders of the Imperial court. The maps made for the Imperial household were printed in only one, two, or a few copies. They were stored in the palace, becoming available for a restricted circle. In view of the monumental size (over 13 m2) of our map, it appears unlikely that it was printed as a commercially intended enterprise. After the defeat of the Ming Dynasty in 1644, many Chinese intellectuals and artists, unwilling to cooperate with the new Manchu rulers, escaped from mainland China. Taking invaluable treasures from the palace during the confusion of the defeat, they moved to Japan where they were allowed to settle down in a restricted area within the port city of Nagasaki. The original Chinese map, made in all likelihood for the Chinese Imperial court, might have been taken to Japan at that time by one of the Chinese literati or civil servants.

This comprehensive, administrative division map can be regarded as a historical material of great value. It is a valuable reference source for the study of the historical geography in the Ming period. Prominence is given to the seats of governments at all levels, the mountain ranges, the major rivers and their tributaries of the empire, as well as the holy Taoist and Buddhist mountains. The Eastern coast lines are not particularly accurate.

SOME INTERESTING DETAILS

The Great Wall, (literally: long fortress, 長城, as written in Chinese) is shown in dotted lines. Five sea-going Chinese boats and three small boats on Dongting Lake, 洞庭湖, in Hunan Province, China’s largest source of sweet water, embellish the map. The highest peaks of the Kunlun Mountains, 崑崙山, are depicted to suggest perennial snow; many mountain passes, looking like gates surrounded by obstacles and frontier garrison posts are pictorially illustrated. Longitudes and latitudes are not indicated. After Matteo Ricci’s stay in Beijing between 1600 and 1610Footnote4, a few maps made by Chinese authors were drawn with meridian lines and latitudes. However, as reported by Ren JinchengFootnote5, in connection with a famous map, the first Chinese attempt to introduce meridian lines, printed in 1644, ‘the obvious improper arrangement of the network of longitudes and latitudes revealed that the author of the map did not fully understand the scientific content of the network’. Since travelling during the Ming Period primarily occurred via the river network, trade routes were only rarely shown on Chinese maps until modern times. The map is quite accurate with a scale of 1 Cun (ca 3 cm) corresponding to 100 Li, approximately 50 km. The distances of all important places, with respect to both Beijing and Nanjing are given in Li, 里.

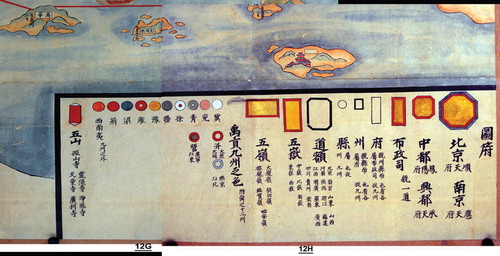

Explanatory legend of the map (in the lower right corner, from right to left) ().

| 1. | large golden octagon: 北京順天府, Beijing, Shuntian Fu, Prefecture of Conforming to Heaven; 南京應天府, Nanjing, Yingtian Fu, Prefecture of Responding to Heaven; | ||||

| 2. | small golden octagon: 中都鳳陽府, Zhongdu Fengyang and 興都承天府, Xingdu, Chengtian Fu; | ||||

| 3. | small golden vertical rectangle: 布政司, Bu Zheng Si, Site of Provincial Administration; | ||||

| 4. | small vertical rectangle: 府, Fu, Provincial and district prefectures, under the authority of the central administration; | ||||

| 5. | small square: 州, Zhou, Districts, under the authority of a prefecture; | ||||

| 6. | small circle: 縣, Xian, Districts, under the authority of a province; | ||||

| 7. | large octagon, black outline: 道額, Dao E, Provinces: (Beijing, Nanjing), 山東 Shandong, 山西 Shanxi, 河南 Henan, 陝西 Shaanxi, 浙江 Zhejiang, 福建 Fujian, 江西 Jiangxi, 湖廣 Huguang, 廣東 Guangdong, 廣西 Guangxi, 四川 Sichuan, 貴州 Guizhou, 雲南 Yunnan; | ||||

| 8. | large golden vertical rectangle: 五嶽, Wu Yue, Five Holy Mountains associated with Taoism, (中山, Zhong Shan, 恆山, Heng Shan, 衡山, Heng Shan, 泰山, Tai Shan, 華山, Hua Shan); | ||||

| 9. | large golden horizontal rectangle: 五嶺, Wu Ling, Five Mountain Chains, (大廋, Dasou; 騎田, Qitian; 都龐, Dupang; 臨賀, Linhe; 始安 Shian); | ||||

| 10. | 禹貢九州之色, Colours representing the nine Zhou (as recorded in the ‘Yu Gong’ chapter of the ‘Shang Shu’)Footnote6; | ||||

| 11. | 并大原大同, Bing Dayuan and Datong, concentric circles (red and white), two cities in Shanxi Province; 燕京以北, North of Yanjing, (old name of Beijing), concentric circles (blue and white); 營廣寧以東, Ying, East of Guangning, concentric circles (red and green), (meaning unclear); | ||||

| 12. | 冀, Ji, white circle; | ||||

| 13. | 西南夷九州之外, orange circle, South-Western minorities (living) outside of the nine Zhou; | ||||

| 14. | 五山, Wu Shan, small vertical red rectangle, five mountain (temples): 徑山寺, Jing Shan; 靈隱寺, Ling Yin; 凈慈寺, Jing Ci; 天童寺, Tian Tong; 廣利寺, Guang Li. | ||||

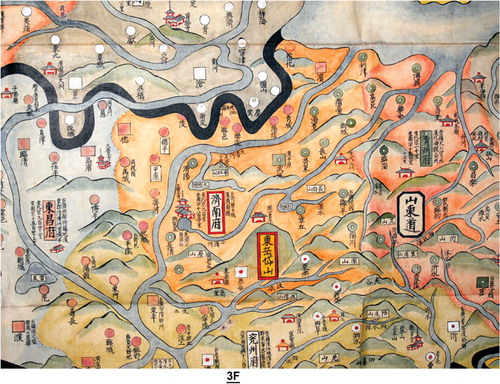

Explanatory notes related to the content of (an arbitrarily chosen representative detail corresponding to about 2% of the huge map) show part of Shandong, 山東, one of the most populous and richest provinces of modern China and part of its neighbouring provinces (modern names: Hebei, 河北 in the North-West; Henan, 河南 in the West and Jiangsu, 江![]() in the South), (old place names during the various earlier kingdoms and dynasties as well as distances from Beijing and Nanjing are given on the map for all important locations). From left to right are shown: a. 東昌府, Dongchang Fu; b. 正覺寺, Buddhist temple, West of Jinan; c. 濟南府, Jinan Fu, capital city of modern Shandong Province; d. North with respect to Jinan, 大明湖, Daming Hu, or ‘large bright lake’, subject of a poem of Du FuFootnote7, 杜甫, e.

in the South), (old place names during the various earlier kingdoms and dynasties as well as distances from Beijing and Nanjing are given on the map for all important locations). From left to right are shown: a. 東昌府, Dongchang Fu; b. 正覺寺, Buddhist temple, West of Jinan; c. 濟南府, Jinan Fu, capital city of modern Shandong Province; d. North with respect to Jinan, 大明湖, Daming Hu, or ‘large bright lake’, subject of a poem of Du FuFootnote7, 杜甫, e. ![]() 州府, Yan Zhou Fu; f. 泰安, the small city of Taian, starting point of pilgrims to the Holy Eastern Mountain; g. 東岳岱山, Dong Yue Dai Shan, Holy Eastern Dai MountainFootnote8; h. 山東道, name of Shandong Province; i. 青州府, Qing Zhou Fu. Two rivers: 大清河, Daqing He and 小清河, Xiaoqing He and four two-story Buddhist temples provided with the character 寺 as well as several smaller ‘house structures’, occasionally carrying the term ‘書院’, probably intended to illustrate ancestor veneration places or monasteries are also shown. The birth place of Confucius, 孔子 (Kong Zi in Chinese), 551–479 BC, 曲阜, Qu Fu, called ‘the city of Lu’ in the remote past, is illustrated in the lower right part of . Mountains and rivers are pictorially portrayed, province borders are indicated with thick black lines, but interestingly the roadway system is not shown on our map and in general on maps of China. The name of the famous Grand CanalFootnote9,Footnote10, the waterway flowing through Shandong Province, West of the city of Jinan, is not inscribed in . However, three cities (臨清, Linqing in Hebei, West of Shandong; 德州, Dezhou, in Shandong, both on (light brown square and light brown circle, respectively) and 濟寧, Jining, in Jiangsu Province, not in ) were located on the map. Since it is well-known that the Canal passes through these cities and its direction between Linqing and Dezhou is clearly North-Eastern, the waterway on the Western edge of , turning eastward at Linqing and crossing three times the thick black province border illustrates in all likelihood the Grand Canal, 運河Footnote11.

州府, Yan Zhou Fu; f. 泰安, the small city of Taian, starting point of pilgrims to the Holy Eastern Mountain; g. 東岳岱山, Dong Yue Dai Shan, Holy Eastern Dai MountainFootnote8; h. 山東道, name of Shandong Province; i. 青州府, Qing Zhou Fu. Two rivers: 大清河, Daqing He and 小清河, Xiaoqing He and four two-story Buddhist temples provided with the character 寺 as well as several smaller ‘house structures’, occasionally carrying the term ‘書院’, probably intended to illustrate ancestor veneration places or monasteries are also shown. The birth place of Confucius, 孔子 (Kong Zi in Chinese), 551–479 BC, 曲阜, Qu Fu, called ‘the city of Lu’ in the remote past, is illustrated in the lower right part of . Mountains and rivers are pictorially portrayed, province borders are indicated with thick black lines, but interestingly the roadway system is not shown on our map and in general on maps of China. The name of the famous Grand CanalFootnote9,Footnote10, the waterway flowing through Shandong Province, West of the city of Jinan, is not inscribed in . However, three cities (臨清, Linqing in Hebei, West of Shandong; 德州, Dezhou, in Shandong, both on (light brown square and light brown circle, respectively) and 濟寧, Jining, in Jiangsu Province, not in ) were located on the map. Since it is well-known that the Canal passes through these cities and its direction between Linqing and Dezhou is clearly North-Eastern, the waterway on the Western edge of , turning eastward at Linqing and crossing three times the thick black province border illustrates in all likelihood the Grand Canal, 運河Footnote11.

Figure 2. Map of China by Sōkaku, 1691, detail, centred at Shandong Province, also showing part of the neighbouring provinces

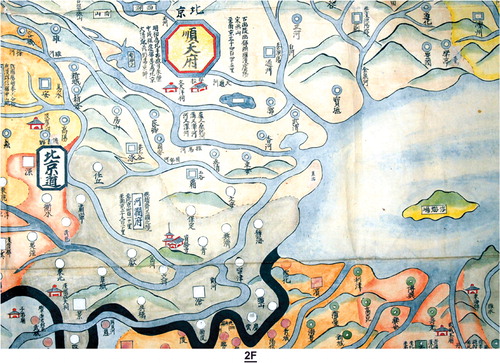

The illustration of the mouth of the Yellow River, 黄河, Huanghe, on our map is of particular interest (). The long river, cradle of the Chinese civilisation, is known to have changed its pathway several times during the past two thousand years. Currently, it flows eastward on the North side of Jinan, the capital of Shandong Province, discharging in the Bohai Sea. Yet, its Eastern terminus or mouth has oscillated from points North and South of the Shandong peninsula in many dramatic shifts over the time. Inspection of is very interesting in this respect in view of the absence of the Yellow River and its mouth. Our complete map as well as other maps portraying the territory of the Ming Dynasty illustrates the mouth of the river further South, in Jiangsu Province. This observation prompted us to consult somewhat later maps of China, drawn by Chinese cartographers. Both the famous ‘blue map’, 大清萬年一統地理全圖, Da Qing Wannian Dili Quantu, Complete Map of the Everlasting and Unified Great Qing Empire, based on a map of 1767 (Biblioth<$>\vskip-1\scale 100%\raster="rg4"\<$>que Nationale, Paris, shelfmark: Rés. Ge A 1096)Footnote12, as well as our own map, dated Jiaqing, Gui Hai, 嘉慶癸亥, 1803, entitled 大清萬年一統天下全圖, Da Qing Wannian Yitong Tianxia Quantu, Complete Map of the Unified Great Qing Empire, drawn by Yang SenzhongFootnote13 show the mouth of the river, discharging into the sea several hundred kilometres South with respect to its current location. Rather than a cartographic error, the illustration of the path and the mouth of the river results from its frequent dramatic change. Historical maps from the Spring and Autumn Period (770–481 BC), the Warring States Period (403–222 BC) and the Qin Dynasty (221–206 BC) indicate that the river was flowing along the border between Hebei and Shandong Provinces before emptying into the Bohai Sea near the modern city of TianjinFootnote14. However, the river changed its pathway in 602 BC, shifting to the South of Shandong, but in 70 AD, returned to its present course. In 1048 it moved again to the North, returning in 1324 to the South of Shandong. The river took its present course as late as the second half of the nineteenth centuryFootnote15.

Figure 3. Map of China by Sōkaku, 1691, detail, 北京, Beijing (large golden octagon), the region surrounding the Northern Capital and the Bohai Sea

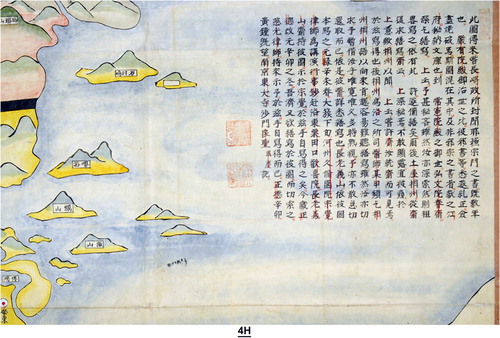

Figure 4. Explanatory text about the history of the map of Sōkaku, 1691, by another monk, detail, on the eastern edge of the map

Explanatory note related to Beijing, 北京 (順天府, Prefecture of Conforming to Heaven): a. (note on the left side of the city) at the beginning of the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644) during the Yongle (永樂) reign, emperor Chengzu (成祖) moved the capital to Beijing; the Qing Dynasty (1644–1912) also established its capital city in Beijing; b. (note on the right side of the city), (the city) was called ‘Youling’ in the remote past, ‘Guang Yang’ during the Yan kingdom and the Han Dynasty, (206 BC–220 AD) and ‘Yan Shan’ during the Song Dynasty (960-1279). The distance from Nanjing is 3445 Li.

Explanatory note related to Nanjing, 南京 (應天府, Prefecture of Responding to Heaven): a. (note, left side) the distance from Beijing is 3445 Li; b. (note, within the octagon) during the Qing Dynasty the prefecture’s name was changed to ‘Jiangning Fu’ (江寧府); c. (note, right side), (the city) was called ‘Jinling’ during the Chu kingdom, ‘Moling’ during the Qin Dynasty, ‘Jianye’ during the Wu kingdom, ‘Jiankang’ during the Jin Dynasty and ‘Jiqing’ during the Yuan Dynasty (1279–1368).

The long explanatory text about the history of the map is provided by its one-time owner or copyist, signing his name as the Buddhist monk, 渉門, 良聖成慶, Shōmon, Ryōsei Jōkei, from the Japanese Southern Capital (Nara)Footnote16, Tōdaiji Temple, 南京東大寺. Although we have translated the complete textFootnote17, we only give here its summary in view of some repetition and unimportant details:

A map of China was (somehow) brought to Japan (probably after the fall of the Ming Dynasty, 1644, by one of the many refugees escaping the Manchu conquest of China). For some time, a number of books related to Christianity were stored at the Nagasaki city administration. During the reign of ‘Genyūin’ (posthumous name of Tokugawa Ietsuna, shōgun 1651–1680), all books (imported from China) were examined and those considered heterodox (propagating Christianity) were destroyed and burned. A map of China was amongst the books. Since the map had nothing to do with the forbidden religion, it was offered to the Edo government and stored in its library. During the reign of Jōkenin (posthumous name of Tokugawa Tsunayoshi, shōgun 1680–1709), (a certain monk) Kōbunin Shunsai expressed the desire to make a copy of the map. (Here follows the names of other persons also intending to make a copy of the map, among them Tsuchiya Saganokami, ambassador of the shōgun at the Kyōto Imperial Court, 所司Footnote18, and the secrecy and hesitations to fulfill their desire). The map (or a copy of it, found in Nagasaki) thus reached Kyōto and was shown to the Buddhist monk, 宗覚, Sōkaku. The latter made a copy of the map during the fourth year of the Genroku period, 元禄辛未, 1691. I, (Ryōsei Jōkei), from the Southern Capital (Nara)Footnote16, Tōdaiji Temple, 南京東大寺, also made a copy of the map during the first year of the Shōtoku period, 正徳元辛卯, 1711. Respectfully written by the monk Ryōsei Jōkei

(This text is followed by two unidentified red ownership seals. The writer does not give any information about the date and author of the original Chinese map featuring the Ming Empire. In view of the unusually large size of the map, Japanese cartographers consider that in all likelihood, the now-lost Chinese map brought to Japan may have been made in the middle of the seventeenth century on Imperial order in one or in a very limited number of originals for the Chinese Imperial household, rather than as a private commercial enterprise.)

Inscriptions of interest on the map

Four famous mountains played an important role in the history of Chinese Buddhism: 五台山, Wutai Shan or ‘Five-Platform Mountain’ in modern Shanxi Province; 峨嵋山, Emei Shan or ‘High Lofty Mountain’ in modern Sichuan Province; 九華山; Jiuhua Shan or ‘Nine Glories Mountain’ in modern Anhui Province and 普陀山, Putuo Shan or ‘Mount Potalaka’ in modern Zhejiang Province.

阿蘭陀, A Lan Tuo, this term in Ming Dynasty Chinese meant Holland. The name appearing in the lower right part of the map, without a well-determined territory, designates Taiwan. On the left side of ‘A Lan Tuo’, two large characters read 南蠻, Nanman, Southern Barbarians, presumably alluding to the inhabitants of the island or to other non Chinese people of South-East Asia. Before the fourteenth century arrival of Chinese people from the continent, the island was inhabited by Malay and Polynesian tribes. The Portuguese called the island Formosa. The island was occupied by the Dutch in 1624. In 1661, General Zheng Chenggong, 鄭成功, captured Fort Zeelandia, ending 38 years of Dutch colonial rule. However, in view of the fidelity to the defeated Ming Dynasty by the established Dongning Kingdom, 東寧王國, Qing forces occupied the island in 1683 and Taiwan was incorporated into Fujian Province, 福建. Therefore, the name of Taiwan, 臺灣 or 台灣 or 台湾 and the island itself is only shown on maps of China portraying the territory of the Qing Dynasty. The actual survey of Taiwan for its accurate knowledge and cartographic illustration only began in 1714.

琉球圖, Liu Qiu Guo, this term designates, although inaccurately, as a single island, the Ryūkyū archipelago, 琉球諸島. While paying tribute to both the Chinese Emperor and to Japan, the kingdom enjoyed quasi independence from the fourteenth to the nineteenth centuries. From the beginning of the seventeenth century, the actual power on the archipelago was exercised by the Shimazu family, 島津,of Satsuma domain, 薩摩, of Kyūshū.

安南交趾, Annan Jiaozhi, this term appears in the lower left part of the Map, without a well-determined territory. It means Annam, the name of the country that the Chinese used referring to modern Vietnam. The Ming armies invaded part of that region several times.

朝鮮國, Chao Xian Guo, Korea, without a well-determined territory; 鴨綠江, Yalu Jiang, the Yalu River, border between Ming China and Korea; 女真, Nü Zhen, Ethnic, called Nü Zhen, dispersed in regions North-East, but outside of China; 沙漠, Sha Mo, (the Gobi Desert); 韃靼諸部落, Da Da Zhu Bu Luo, Da Da Mongol Tribes, inscription on the top part of the map, but outside of Chinese territory.

CONCLUDING NOTE

This article illustrates and discusses the main features of a monumental hand-coloured manuscript map of the late Chinese Ming Empire of which only two other copies, both in Japan, are known. The comprehensive, administrative division map, an important item of historical significance, is a valuable reference source for the historical geography of the Ming period, 1368–1644. It highlights the government seats of the various provinces, the major rivers, mountain ranges, as well as material of historical importance.

BIOGRAPHICAL NOTES

Dr Gabor Lukacs, PhD, Universit<$>\vskip-1\scale 100%\raster="rg5"\<$> de Paris, 1964. Retired scientist and japanologist. Born in 1937 in Budapest, Hungary. Author of about 160 scientific papers. Wrote and published three books about Japanese medicine and cultural history: Kaitai Shinsho & Geka Sōden. Hes & De Graaf Publishers, Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2008. Extensive Marginalia in Old Japanese Medical Books, Wayenborgh Publisher, Piribebuy, Paraguay, 2010 (European and North American distributor: Kugler Publications, Amsterdam, The Netherlands). Chinese Dermatology on a Japanese Handscroll (with Alain Briot), Wayenborgh Publisher, 2012.

Notes

1 Unno Kazutaka (2005). Tōyō-Chirigakushi Kenkyū (Monographs on the History and Geography in the East), pp. 488–505, Seibundō, Ōsaka.

2 The Shingon Esoteric Sect had considerable following in Japan since its introduction from China during the first years of the ninth century by Kūkai, 空海 (posthumously known as Kōbō-Daishi, 弘法大師, 774–835), with headquarters in Kōyasan, 高野山.

3 In addition to our map, two other manuscript versions are known: a. Ōsaka, Kushūon In Shozō, (大阪久修園院所蔵, Collection of the Ōsaka Kushūon Temple) and b. Kōbe Shiritsu Hakubutsukan, (神戸市立博物館, Kōbe City Museum). However, the Kōbe Museum copy does not have the manuscript text relating the map’s history shown in of our map. Since neither Professor Unno Kazutaka, nor other well-known specialists of Sino-Japanese cartography (Professor Li Xiaocong, Beijing, Professor Myoshi Tadayoshi, Kōbe) have been able to identify the name of the original Chinese map’s author or the exact time when it was made, the original map may no longer exist.

4 Fontana, Michela, 2010. Matteo Ricci, (1552–1610), (Salvator, Paris).

5 Ren Jincheng, map no. 146, entitled ‘Complete Map of Allotted Fields, Human Traces, and Travel Routes Within and Without the Nine Frontiers under Heaven, ‘天下九![]() 分野人迹路程全圖’ in Cao Wanru, Zheng Xihuang, Huang Shengzhang et al., 1994., An Atlas of Ancient Maps of China, vol. II., Note on Plates, p. 36 (Cultural Relics Publishing House, Beijing).

分野人迹路程全圖’ in Cao Wanru, Zheng Xihuang, Huang Shengzhang et al., 1994., An Atlas of Ancient Maps of China, vol. II., Note on Plates, p. 36 (Cultural Relics Publishing House, Beijing).

6 The Shangshu, 尚書, ‘Documents of the elder’, also called Shujing, 書經 ‘Book of documents’, is one of the five ancient Confucian classics (wujing, 五經). It is a collection of speeches made by rulers and important politicians from mythical times to the mid of the Western Zhou period, 西周 (eleventh century–770 BC). The Shangshu consists of five parts. Especially noteworthy is the chapter Yugong which is a description of how the mythical emperor Yu the Great tamed the floods and divided China into provinces, giving each province a quality label for its soils, tributes and local products. This chapter must have been added later, at a point of time when China has obtained her traditional geographic extent, presumably during the late Warring States, 戰國 (403–221 BC) or even the early Han period, 漢 (206 BC–8 AD). Cai Shen 蔡沈, a disciple of the great Neo-Confucian scholar Zhu Xi, assembled all Sung period commentaries on the Shangshu and published them as Shujizhuan, 書集傳, in 6 juan. The Shangshu, or Shujing, as it was called from then on, had to be studied by all those wishing to pass the state examinations. During the Ming period, 明 (1368–1644), therefore, it was part of the book Wujing daquan, 五經大全, ‘All about the Five Classics’, which served as a kind of textbook for candidates of the state examinations (Wikipedia).

7 Du Fu, 杜甫, 712–770, one of China’s most famous Tang Dynasty poets.

8 Because of its location, the 1545-m high mountain is associated with the rising sun, signifying birth and renewal; it is regarded as the most sacred of the Five Holy Mountains.

9 The Grand Canal, 京杭大運河, connecting Hangzhou with Beijing, the world’s longest artificial waterway, ca 1700 km, was in large part a creation of the Sui Dynasty, 581–618, as a result of the migration of China’s core economic and agricultural region away from the Yellow River valley and toward what are now Jiangsu and Zhejiang provinces. Its main role throughout its history was the transport of grain to the Northern capital. It was almost completely renovated between 1411 and 1415, during the early part of the Ming Dynasty.

10 Brook, Timothy, 1998. The Confusion of Pleasure: Commerce and Culture in Ming China (University of California Press, Berkeley).

11 Cao Wanru, Zheng Xihuang, Huang Shengzhang et al., 1994. An Atlas of Ancient Maps of China, Vol. II, note attached to plate no. 84 (Cultural Relics Publishing House, Beijing), ‘In Shandong’s central section, the water of the canal is mainly provided by the springs of the province. During the Ming and Qing Dynasties, in order to keep up the water transport of grain to the capital and ensure water supply for the canal, large scale surveys of the sources of the springs from the mountainous regions of Shandong were conducted’.

12 Monnet, Nathalie, 2004. Chine, L’Empire du Trait, Exhibition Catalogue, pp. 12–13 (Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris).

13 Famous cartographer, 1694–1771 also known as Huang Zhengsun (黄証孫), native of Zhejiang Province. Wikipedia.

14 Cao Wanru, Zheng Xihuang, Huang Shengzhang et al., op. cit., note attached to plate no. 102; ‘In 1855, the river changed its course at Tongwaxiang, Henan and then flowing wantonly over the level ground along Dongming, Puzhou and the Fanxian County, it broke through the Grand Canal at Zhangfu County, forced upon the Dapinghe River and got to Lijin County where it emptied into the Bohai Sea’.

15 In a map, entitled ‘Flood-Prevention Work on the Yellow River’, Wan-li Period, 1573–1620, the course of the river is commented as follows: ‘The Yellow River, starting from its source, flowing through present-day Qinghai, Gansu, Ningxia, Inner Mongolia, Shaanxi, Shanxi and Henan, merging with the Grand Canal near Xuzhou (Jiangsu), breaking away from the Canal near Huai’an, takes over the Huai River before finally emptying into the sea’; see, China: In Ancient and Modern Maps, 1998, map no. 83, (London, Sotheby’s Publications).

16 Nara was Japan's capital city from 710 to 794, when the capital was transferred to Kyōto.

17 The text was very carefully studied, annotated and punctuated in red by a later owner of the map. He used the very strict annotating code characteristic of Japanese scholars, facilitating the reading and understanding of texts: a. name or function of persons: one bar in the centre of the text; b. place names: one bar on the right side; c. Japanese chronological period names: two bars on the left side; d. book or document names: two bars in the centre.

18 Tsuchiya Sagaminokami, 土屋相模守, (政直, according to Wikipedia, Tsuchiya Masanao) 1641–1722, Shoshi, 1685–1687; Rōjū, 老中, 1687–1718, one of the highest ranking government post during the Tokugawa regime.