Abstract

The history of Christian pilgrimage in Syria-Palestine has captivated scholarly and public audiences since the first waves of research in the region in the nineteenth century. This subject continues to generate vibrant debate among scholars of Late Antiquity and the early Middle Ages. Central to this discourse is John Wilkinson’s seminal publication Jerusalem Pilgrims before the Crusades, first published in 1977. This text still offers the most systematic study of descriptions of pilgrimage to the region between the fourth and eleventh centuries, yet in spite of its popularity and central status to the subject, few of the texts collected in Wilkinson’s volume have received systematic study as literary compositions in their own right, or as products of individual writers and communities. This article offers an overview of issues which have emerged from a preliminary study of one of the texts published in the revised second edition of Jerusalem Pilgrims in 2002: Bede’s De locis sanctis, a survey of the ‘holy land’ written in Anglo-Saxon Northumbria at the turn of the eighth century.

John Wilkinson’s Jerusalem Pilgrims before the Crusades, has been influential in stimulating and sustaining interest in early medieval pilgrimage to the Christian ‘holy land’ since it was first published in 1977. Wilkinson’s research benefitted from an intimate familiarity with the region which he gained from living in Jerusalem for many years, first as Canon of St. George’s Cathedral and subsequently as Director of the British School of Archaeology in Jerusalem (1979–1984). No other work has made such a complex repertoire of sources, written in different ancient languages and spanning a diverse range of social contexts and time periods, so readily accessible in English translation. Although nearing the fortieth anniversary of its publication, the fact that the volume remains at the core of debates about early Christian pilgrimage testifies to its enduring contribution to several different academic disciplines. Although each item in the collection attests to the continued intellectual allure of Jerusalem for medieval audiences, the works compiled in Jerusalem Pilgrims before the Crusades were written in substantially different social and religious contexts from one another; how widely these distinctions impacted upon perceptions of the holy land in early medieval minds has yet to be widely explored.

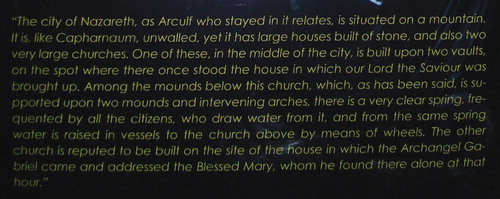

The fact that many of the works compiled in Jerusalem Pilgrims survive in only a handful of copies or less should encourage us to seek a more intricate understanding of the people for whom these texts were originally produced; how they were intended to be read; and the intellectual questions about Jerusalem they were designed to address. Indeed, the very success of Jerusalem Pilgrims within early medieval studies has exposed these works to a larger array of interpretations and readings than they may have ever received from their initial medieval readerships. Scholarly focus on these texts has primarily remained concerned with questions of geographical accuracy and studies continue to emerge which are aimed at grounding the descriptions in tangible archaeological and historical ‘realities’. The practice of displaying extracts from the texts on tourist information boards at churches frequented by modern pilgrims, such as at the Church of St Joseph in Nazareth (), offers one example of a perception of them as straightforward factual descriptions which can be encouraged when such texts are only considered in respect to what information they can relay about the historical evolution of the Levantine holy land and not the communities or individuals who composed them.

Fig. 1:. Placard bearing information concerning ‘Arculf’s pilgrimage’, Church of St Joseph, Nazareth

The reasons for this are entirely understandable. In a number of cases where modern churches overlie the earlier buildings, as with many of the churches on the Mount of Olives, the textual accounts compiled in Jerusalem Pilgrims often supplement the limitations of the archaeological record. For Jerusalem itself, the accounts of the journeys undertaken by the Anglo-Saxon traveller Willibald in the 720s, Bernard the Monk in c.867 AD, and Epiphanios Hagiopolites at some point between the seventh and ninth centuries offer the most extensive surviving descriptions of the city between 630 AD and 1096 AD which, after over a century of research, is still the most poorly understood phase in Jerusalem’s history. Nevertheless, enthusiasm for basing an understanding of early medieval pilgrimage in the Levant on these so-called ‘pilgrim texts’ needs to be exercised delicately. Archaeological research in the region continues to identify Christian cult sites that remained in use until the ninth century but which are entirely absent from the descriptions gathered together within Jerusalem Pilgrims. The large cenobitic centre of Jabal Harūn in the Transjordan offers a prominent example often invisible to the accounts of western writers. These sites co-existed with an equally complex landscape of smaller churches and cult sites incorporating natural caves or pre-existing Roman tombs. The sites of the North Church in Rehovot-in-the-Negev, Horvat Hani () and Horvat Qasra are important to note in this regard and indicate the complexity of early medieval spiritual landscapes in Syria-Palestine (Dahari Citation2003; Kloner Citation1990). The presence of graffiti at Rehovot-in-the-Negev and Horvat Qasra, in Greek, Arabic and Syriac, presents valuable insights into alternative devotional landscapes which were actively endorsed by local populations rather than travellers from outside the region. Sites such as these offer the potential to transform our understanding of the Christian holy land and its physical extent during the first millennium. As the corpus of such sites expands, this will require us to resituate texts such as those translated and collected in Jerusalem Pilgrims before the Crusades within a much broader discourse of archaeological research and literary criticism.

The Latin tract De Locis Sanctis, or On the Holy Places, a description of the holy land by the Northumbrian monk the Venerable Bede (c. 673-735), presents one example of a text produced in authorial and social environments which are sufficiently researched enough to facilitate a deep analytical treatment of it. The study of Bede’s writings and thought remains a very active area of scholarly interest and is complemented by a much broader framework of archaeological and literary research which furnishes a sophisticated understanding of the physical, intellectual and social worlds in which Bede lived (DeGregorio Citation2006; Brown Citation2009).

Bede’s De locis sanctis (hereafter DLS) was omitted from the first edition of Jerusalem Pilgrims, but it was included in the revised second edition because of the considerable authority that Bede and his writings came to exert (Wilkinson Citation2002, iv). It is, on the surface, a relatively straightforward description of a series of important holy land locations, but it is important to recognise that (like the other texts in Wilkinson’s collection) it is framed by distinct intellectual and religious contexts which had a significant impact upon the way that Jerusalem was conceptualized by its author. First of all, it is important to emphasise that Bede never set foot in the Levant. Indeed, it is very unlikely that he ever ventured very far beyond the twinned monasteries at Wearmouth and Jarrow in Anglo-Saxon Northumbria in which he resided from the age of seven onwards. Now best known for his magisterial Ecclesiastical History of the English Nation (Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum; hereafter HE), Bede’s reputation in the Middle Ages was first and foremost built upon his skill as a biblical commentator. Because the landscape of the holy land was the setting for much of the action of the Old and New Testaments, gaining an understanding of the development of that landscape through time was a serious concern for many educated Christians in the medieval period, Bede included. Despite being neither resident nor visitor of the holy land, Bede’s attitude towards that region is worth examining for what it can reveal about how Jerusalem and the area surrounding it were understood in the far reaches of the West at the turn of the eighth century.

Bede’s DLS is a much understudied text. Commonly held to be one of his very earliest compositions and dated to around the year 703 AD (Brown Citation2009, 71), the tract is very dependent on earlier written sources for its content. In particular, Bede relies heavily upon the text of the same name by Adomnán of Iona, a debt explicitly acknowledged by Bede in the closing paragraphs of DLS and again in the HE (V.17). Bede’s DLS offers short descriptions of a series of locations, starting in Jerusalem and working broadly outwards; the survey takes in Hebron, Jericho, the Sea of Galilee, Damascus and Alexandria along the way, before finishing in Constantinople. At face value, this text might be easily overlooked due to: its brevity; the largely derivative nature of its content; Bede’s geographical separation from the sites he wrote about yet never visited and significant gaps in coverage. Although it has not captivated many contemporary scholars, DLS was frequently copied by Bede’s medieval audiences, and it survives in at least 47 medieval manuscripts (Laistner and King Citation1943, 83–6); this means that in the centuries after his death a significant number of intellectuals, tutors and pupils formulated their mental images of the Levantine region with help from Bede’s text. Bede himself valued the work highly enough to include four of its chapters in the account of Adomnán’s life presented in the final part of the HE (V.15–17). The enduring popularity of the HE through the medieval, early modern and modern eras has ensured that Bede’s descriptions of Bethlehem, the Golgotha-Sepulchre complex, the Mount of Olives and Patriarchs’ tombs at Hebron have been consulted by countless generations of readers since the HE was first issued in 731 AD.

As Wilkinson recognized, Bede’s DLS occupies an important place in scholarship on the medieval holy land because it was responsible for transmitting information set down by earlier authorities to a wide audience (Wilkinson Citation2002, 21). In terms of factual content, when handling Bede’s DLS we must bear in mind that it is a remodelled and edited version of Adomnán’s earlier tract of the same name, although in the epilogue to his own DLS Bede informs us that he had checked Adomnán’s treatise against other textual sources at his disposal. Adomnán tells us that his principal informant was a Gaul named Arculf, a bishop who had spent nine months residing in Jerusalem and travelling extensively throughout the Levant. It is claimed that Arculf relayed his experiences to Adomnán in person; the latter made notes of those conversations before subsequently issuing a definitive version. This outline of events is repeated by Bede in the epilogue to his own DLS and HE V.15, and Bede adds some intriguing layers to the tale: blown off course on a sea voyage back to his homeland, Arculf ended up on the west coast of Britain and encountered Adomnán ‘after many adventures’. From Bede we learn that Adomnán’s tract was transmitted to Anglo-Saxon England when a copy was presented to King Aldfrith of Northumbria (d. 705) by Adomnán himself. The king had the text copied and circulated amongst the literate elite of Northumbria in the late seventh century.

Adomnán and Bede’s statements about Arculf have sometimes been treated with scepticism, most notably by O’Loughlin, whose 2007 monograph Adomnán and the Holy Places offers a thorough examination of the Arculf story and casts doubt upon its historicity. His study treats Adomnán’s text as a highly sophisticated exegetical work. O’Loughlin demonstrates that the status claimed for Arculf as a trustworthy eyewitness is called upon at various junctures in Adomnán’s text in order to resolve difficult issues, such as contradictions arising in the Scriptures concerning the location or features of a particular holy site: in such instances, the word of the eyewitness holds sway and the conflict is resolved by deferring to Arculf’s authority. O’Loughlin’s conclusions are especially important given that information derived directly from Adomnán’s account of ‘Arculf’s pilgrimage’ has sometimes been used without qualification as first hand evidence in studies of the topographical development of some holy land sites in the medieval period; such information can also be found on placards for tourists at some locations in the present day (see ). Despite its limitations, Adomnán’s DLS contains information about the sacred topography of the Levant in the late seventh century which is not attested elsewhere. Statements about two places of worship established by the Umayyads, one in Damascus, and another on the Temple Mount / Haram al-Sharif in Jerusalem (II.28 and I.1 respectively), hint that Adomnán had access to information about those locations that was relatively up to date at the time of writing.

In the revised second edition of Wilkinson’s Jerusalem Pilgrims, translations of Bede’s DLS and Adomnán’s earlier offering of the same name are separated by a tract known as The Holy City and the Holy Places by Epiphanios: a rarely studied text dated between the seventh and ninth centuries. One of the principal purposes of our research trip to Jerusalem in December 2013 was to gain a better understanding of the relationship between Bede’s DLS and its principal source by visiting some of the places that they describe, including: the Golgotha-Sepulchre complex, Mount Zion, the Valley of Jehoshaphat and the Mount of Olives; as well as several locations further afield including: Bethlehem, the River Jordan, Capernaum, Nazareth and the Sea of Galilee. Although many of those places have undergone considerable physical changes since the early eighth century, occasionally some aspects of a description of a site by Bede can still resonate with a present-day location; for example: the Chapel of the Ascension on the Mount of Olives (), despite being a much later structure in its present form, shares some general features with a church described by Bede in DLS 6 in which the last footprints of the Lord were said to be visible ().

Visiting some of the sites mapped in Bede’s text in sequence only serves to reinforce the long-held notion that the DLS cannot, in any sense, be considered a guide to the City of Jerusalem for contemporary travellers, since the order in which Bede presents those sites to the reader does not make, and cannot ever have made sense as an actual physical journey. Such an exercise did, however, facilitate an important insight which may shed some light on the intentions of Bede’s text, and which serves to underline what is distinctive about it. Whilst the text of Bede’s DLS is heavily influenced by Adomnán’s, reading them side by side makes it clear that Bede thoroughly reordered the structure of his principal source text. Adomnán’s treatise begins with a survey of Jerusalem’s walls, gates and towers, a choice which has been linked to Psalm 48 which commands: ‘Walk about Zion, go around her, count her towers, consider well her ramparts, view her citadels, that you may tell of them to the next generation’ (New International Version; O’Loughlin Citation2007, 35). One of the first stations on Adomnán’s journey around the city is the Temple Mount / Haram al-Sharif, which is said to be home to a wooden house of prayer which can hold up to 3,000 ‘Saracens’ (Sarraceni) at a time (I.1). Bede retained the initial topographical description of Jerusalem as a walled city but began his DLS in the Martyrium, the great basilica commissioned by Emperor Constantine to celebrate the ‘rediscovery’ of the True Cross by his mother Helena; Golgotha and the Sepulchre, the locations believed to have witnessed Christ’s death and resurrection respectively, were linked together by this fourth-century complex. Bede’s description of the Martyrium is taken over from Adomnán, but the structural reordering establishes Golgotha and the Sepulchre as the central loci of the city, bringing the sites of the Passion and Resurrection front and centre.

Intriguingly, the very last location described in Bede’s DLS is another Constantinian basilica: the Hagia Sophia in Constantinople (Chapter 19). Again taking his cue from Adomnán, Bede tells us that the church housed three fragments of the True Cross, and so Bede’s text is bookended by two sites connected to that particular relic (in contrast, the final location charted by Adomnán is Vulcano, an island off the coast of Sicily). Although the words used by Bede in DLS were often borrowed from earlier accounts, by carefully reordering his source texts Bede constructed a new mental map of the holy places which is distinctly Passion-centric. Further research will be necessary to assess the significance of this careful editorial work, but such endeavours could potentially have important consequences for the way that Bede’s early-career writings are viewed in contemporary scholarship. DLS has often been dismissed as simplistic and naïve, but perhaps it is shot through with flickers of the creative intellectual current which would come to define much of the rest of Bede’s output (see further DeGregorio Citation2006).

Our initial work with Bede’s DLS and Adomnán’s tract of the same name suggests that although on the surface they have a lot in common, the differences between these two texts are significant. There is scope for further research to be done on these tracts, the others that sit with them between the covers of Jerusalem Pilgrims, and sources omitted from both editions of Wilkinson’s book. Wilkinson’s study has encouraged us to view its collection of texts as a sequential repository of factual information about the evolving landscape of the medieval Levant, which together form something approaching a distinct genre of literature. Further study of these and other connected sources should re-evaluate their historical settings and authors’ intentions on a case-by-case basis. An important aspect of this endeavour will be the collaboration of several scholars from a wide range of subject backgrounds to reflect on the considerable legacy of John Wilkinson’s research; indeed, such cross-disciplinary collaboration will be necessary in order to do justice to the panoptic ambitions of Wilkinson’s impressive and influential collection.

Notes on Contributors

Peter Darby is Lecturer in Medieval History at the University of Nottingham. His research focuses on ecclesiastical history, with particular emphasis on Anglo-Saxon England and the writings of Bede. He is the author of Bede and the End of Time (Ashgate, 2012).

Daniel Reynolds has recently completed his doctoral thesis Monasticism and Christian pilgrimage in early Islamic Palestine c.614–c.950 at the University of Birmingham. He is British Academy Postdoctoral Fellow at the University of Birmingham, where he is undertaking a research project: ‘Forging the Christian Holy Land 300-1099’ (from September 2014).

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to the CBRL for awarding us linked travel grants (‘The 614 Project’; ‘Jerusalem and Jarrow in the early eighth century’) which enabled us to visit several of the locations mentioned in this article. We would also like to thank Dr Carol Palmer, for giving us the opportunity to write about our research, and Maida and the other staff at the Kenyon Institute for assisting us during our stay. Dan Reynolds also wishes to thank Uzi Dahari for his advice and hospitality.

References

- Adomnán, De locis sanctis, ed. L. Bieler (1965) Corpus Christianorum Series Latina 175, 183–234.

- Bede, De locis sanctis, ed. J. Fraipont (1965) Corpus Christianorum Series Latina 175, 244–80.

- Bede, Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum, ed. and trans. B. Colgrave and R.A.B. Mynors (1969) Bede’s Ecclesiastical History of the English People. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Brown, G. H.(2009) A Companion to Bede. Woodbridge: Boydell Press.

- Dahari, U.(2003) The excavation at Horvat Hani. Qadmontiot 36, 102–106 (in Hebrew).

- DeGregorio, S.(2006) Innovation and Tradition in the Writings of the Venerable Bede Morgantown, WV: West Virginia University Press.

- Kloner, A.(1990) The cave chapel of Horvat Qasra. Atiqot 19, 29*-30* (in Hebrew).

- Laistner, M.L.W. and King. H. H.(1943) A Hand-List of Bede Manuscripts. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- O’Loughlin, T.(2007) Adomnán and the Holy Places: the Perceptions of an Insular Monk on the Locations of the Biblical Drama. London: T&T Clark.

- Wilkinson, J.(2002) Jerusalem Pilgrims: Before the Crusades. Revised and updated second edition. Warminster: Aris & Phillips Ltd.