Palaeoenvironments of the Late Glacial Transition in the Eastern Desert of Jordan

Matthew Jones (University of Nottingham)Tobias Richter (University of Copenhagen) and Gary Rollefson (Whitman College); email: [email protected]

The last glacial-interglacial transition (LGIT), between 20 and 10 ka BP, saw a global reorganization of climate, as ice caps melted, and a revolution in the way people lived, as agriculture developed. Understanding the spatial and temporal patterns of environmental change over this time period is therefore of interest to a range of disciplines. There are few long-term continuous records of environmental change from Jordan, or the natural archives where these may be found, and yet the eastern desert contains evidence of a long, and sometimes complex, occupation history, suggesting environments in the past were significantly different to those of today. Such evidence indicates that a resource base was available for these communities to survive, or that ancient cultural economies were significantly more advanced than we currently give them credit for. From a palaeoclimate perspective, spatial patterns of environmental change differ through the LGIT in regions north and west of Jordan compared to Arabia and North Africa so understanding where Jordan sits in this regional divide is important for understanding global climate structure through this transition.

This project aims to further our understanding of Late Pleistocene and early Holocene environments in Jordan’s eastern desert. Specifically, the project is investigating the hydro-environment of locations associated with occupation during this time period. Archaeological evidence suggests that the study sites, Qa Shubayqa and Wisad Pools, were more suited to occupation in the past than at present, and we hypothesize that this was in part due to a natural environment with increased water availability.

The Qa Shubayqa, which lies 25 km north of Safawi, is a relatively large playa that is used fairly extensively for seasonal agriculture today. Recent archaeological excavations at Shubayqa have shown a long history of occupation around the qa from the LGIT onwards. The Wisad Pools are a series of basins in a c. 1 km long wadi in the basalt desert 100 km east of Azraq. Excavations and survey over the last 5 years have found evidence of occupation of the area from the Epipalaeolithic onwards, with significant stone hut structures of Late Neolithic age suggesting semi-permanent occupation 8–8.5 ka BP.

The first fieldwork as part of this team-based award took place in August 2013. This was largely a reconnaissance season to assess requirements for work at the two sites in the second year of the project and to assess their potential for palaeoenvironmental work. In addition, time was spent at the site of Kharaneh IV to continue work at this earlier occupation site as part of the Epipalaeolithic Foragers of Azraq Project. Together, the three sites provide human occupation periods before, during and after the glacial- interglacial transition, and therefore potential windows into the palaeoenvironments of these times. Detailed work at the Wisad Pools will take place in the summer of 2014 focussing on the qa sediments at the base of the wadi and detailed mapping of the pools themselves to allow calculations of potential water storage through time.

At Shubayqa, two sedimentary sequences from the qa were sampled and are currently undergoing analysis. Physical characteristics of the sediments, such as grain size and elemental composition, are being analysed to look at changes in sedimentation and flow regimes into the qa, and slides are being prepared for microfossil analysis (pollen and diatoms) to help interpret the regional environment. The qa contains at least 4.5 metres of sediment which preliminary age estimates show as Holocene in age.

The field observations and preliminary analysis of off-site sediment samples confirm that these two sites must have experienced considerably different climatic and/or geomorphological conditions in the past, compared to today. The timing of these changes in condition in relation to the occupation sites remains to be confirmed and will be a focus of research during the rest of this project. In addition, the second year of the project will aim to model the climatic conditions that would be required to ensure available water at these locations during the time period of interest and compare this to regional evidence of hydroclimatic change. By reconstructing the past hydrological conditions for the sites, we hope to improve our understanding of the environmental history of eastern Jordan and the lifestyles of its early occupants.

We thank Matthew Williams for his help in the field and The Council for Independent Research Culture and Communication and The Danish Institute in Damascus for additional funds that supported this work.

Hunting in Prehistory—Understanding the Role of Wildlife

Louise Martin Elizabeth Henton and Andrew Garrard (Institute of Archaeology UCL); email: [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]

Several decades of archaeological excavation and research in the eastern Jordanian badia demonstrate that hunter-gatherers during the Epipalaeolithic and early Neolithic found abundant wildlife there. Even after the later Neolithic when sheep and goat herding was first introduced, the steppes and deserts continued to serve as rich hunting grounds into the 20th century. Animal bones studied from over 30 archaeological sites in the badia, dated between 22,000 and 5,500 cal BC, show that the characteristic steppe animal—the goitered or Persian gazelle—was the prime focus of hunting. Other large game such as onager (Asian wild ass), wild horse, aurochsen (wild cattle), and smaller prey such as birds, hare and fox, were also exploited.

Our current three-year Leverhulme Trust funded project focuses on understanding the nature of wildlife hunting in the steppes, particularly of gazelle, during the period 22,000-5,500 cal BC (Early Epipalaeolithic to Neolithic). In the Early Epipalaeolithic at ‘megasites’ such as Kharaneh IV and Wadi Jilat 6 in the limestone steppes, it is likely that seasonal availability of gazelle drew large aggregations of hunter-gatherers to hunt there. One of our key aims is to reconstruct seasonal mobility of past gazelle herds to assess how herd behaviour may have influenced hunting strategies. Large migratory game herds, for example, lend themselves to intercept hunting and the use of animal drives, whereas smaller dispersed herds may have necessitated animal stalking or trailing. The choice of hunting strategy can have implications for hunter-gatherer social organization, in terms of access rights to game, how hunters are organized (communally or smaller groups), and how carcasses are shared and processed.

We are modelling late Pleistocene to early Holocene shifts in wildlife distributions, behaviour and mobility in the badia, which may have resulted from adaption to major climatic and environmental changes. In addition, as Neolithic settlement expanded into the steppe during the PPNB (Pre Pottery Neolithic B), gazelle-hunting strategies may have changed and wildlife become subjected to hunting pressure. The introduction of domestic livestock—sheep and goats—in the later Neolithic is likely to have had a profound impact on existing wildlife. Our research has three main methodological dimensions: analysis of bone assemblages recovered from archaeological sites, much of which has already been undertaken; the use of two relatively new archaeological science techniques, isotopic analysis and tooth microwear; and computer based (GIS) modelling.

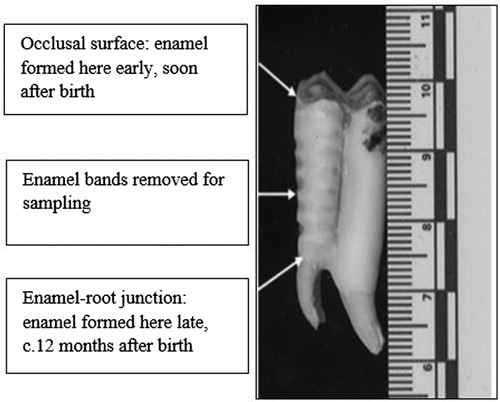

Conventional animal bone studies from the 30 Epipalaeolithic and Neolithic sites—including Kharaneh IV, the Azraq Basin Project sites, Black Desert sites (Dhuweila, Burqu), and Shubayqah—show the results of hunting encounters. New archaeological scientific approaches aid the reconstruction of living wildlife behaviour. Isotopic ratios of strontium, carbon and oxygen in gazelle tooth apatite provide direct information on location, diet and seasonality in the early stages of gazelles’ life histories. Incremental samples are taken through dental enamel, as seen in the figure above.

In spring 2013, under the auspices of a ‘documentation permit’ from the Department of Antiquities (DoA), we conducted a modern plant collection fieldtrip in the badia to create a baseline study of contemporary isotopic ratios, or ‘signatures’. This is required to understand our archaeological isotopic data. Plant samples were collected from a range of bedrock environments, and exported with kind permission from the DoA. Analytical work is currently underway in University of London laboratories. We are extremely grateful to Carol Palmer (CBRL) and Isabelle Ruben (Amman), for their botanical expertise on this collection trip, and to Mr Osama Lutfi of the Department of Antiquities for his help and guidance.

The second archaeological science method we employ is that of dental microwear—the patterning of microscopic scratches and marks—on gazelle teeth to provide information on animal diet in the weeks preceding death. This patterning provides information on the type of feeding environment animals inhabited in the season they were hunted; for example, lush, fresh spring shoots or coarser woody plant materials from later in the year.

Computational modelling of the palaeoenvironments of the badia is being undertaken by Joseph Roe, a PhD student at the Institute of Archaeology, UCL. The first stage is to investigate the effect of different climatic variables on gazelle ranges, mobility and likely densities across various vegetation zones and different seasons using GIS-based methods for reconstructing ecological niches. The second stage is to explore the inter-relationship between changing gazelle seasonal mobility and human hunting strategies using what is referred to as an agent-based model. The GIS mapping of the badia will be available to other users in due course.

Through a combination of the above approaches we intend to produce a synthetic and testable view of how hunters and wildlife interacted in the steppe and desert landscapes of eastern Jordan. We are very grateful to the Leverhulme Trust who are supporting this study through Research Project Grant RPG-2013-223, and CBRL for support through project affiliation.

Arid Southern Levant: Environmental Reconstruction of the ‘Desert Wetlands’ in the Last c. 40,000 Years

Claire Rambeau (University of Bern); email: [email protected]

In the most arid parts of the Southern Levant, palaeo-environmental records are rare and often incomplete, usually due to bad preservation in dry climates. Organic deposits from the rain-shadow area bordering the Dead Sea to the north east (the co-called ‘EDS’ sites) and in the vicinity of Faynan archaeological sites in southern Jordan (Fidan sites) offer the opportunity to bridge a gap in knowledge regarding the specific environmental evolution of the driest parts of the Southern Levant during the last c. 40,000 years. Fed by internal springs, these archives developed in small wetlands and contain pollen information that allows for the reconstruction of the local to regional vegetation history. Together with geochemical investigations, this provides a glimpse of environmental and climate shifts throughout the Late Pleistocene and Holocene.

Fieldwork in January and February 2012 provided cores from two wetlands in the EDS zone, EDSA and EDS8, which presently receives an average annual rainfall of c. 150 mm. Today, the site is located in the Irano-Turanian vegetation zone, but due to its close vicinity to the Mediterranean vegetation zone (Madaba plateau), the area would have been highly sensitive to past climate changes. Radiocarbon dating of plant macrofossils from the wetland EDSA cover the last c. 8,000 years, and radiocarbon dating on bulk organic sediments and deposits from EDS8 cover the last c. 33,000 years (additional dates on plant remains are expected for the near future). The organic layers of both EDSA and EDS8 are extremely rich in pyrite, a mineral that obscures pollen slides when prepared with standard pollen extraction techniques. However, an adapted procedure has been designed and pollen extraction was successful and allowed for a reconstruction of vegetation changes for both EDSA and EDS8.

Dr Carol Palmer from the CBRL British Institute in Amman also identified wetlands in the Fidan area close to Faynan, which has an average annual rainfall of c. 60 mm. After a reconnaissance survey, the wetland FI30 was selected and cored in June 2013. Unfortunately, most of the sequence at FI30 consists of gravels and intercalated clay layers in which pollen is usually not preserved. However, an organic layer of about 50 cm, containing pollen, located towards the bottom of the sequence, allows for a snapshot of the vegetation composition at Fidan for the late Pleistocene (c. 48,000-17,000 BP). Preliminary radiocarbon dates obtained on bulk sediment can be compared to data from the uppermost sediments which also contain pollen (additional dates on plant remains are expected for the near future).

EDS8: The wetland EDS8 in the EDS zone. EDS8 was excavated in recent times to get access to the hidden spring, but parts of the wetland are still intact. Picture taken in January 2012

The EDS archives show very little indication of human influence in their Holocene pollen records, which makes them a rarity in the Southern Levant. All records suggest that no drastic vegetation change occurred in the arid and semi-arid parts of the Southern Levant during the last c. 45-30,000 years; the vegetation growing at and near the sites indicates a steppe environment for the whole period. The EDSA sequence displays specific vegetation changes, mostly in wetland species such as Typha (bulrushes), as well as in the locally growing species Chenopodiaceae (goosefoot family), Cichorioideae (a sub-division belonging to the daisy family), and Gramineae (grasses), and to a lesser extent, Phoenix (date palm). Similarly, EDS8 shows major variations in the same species, as well as in Cyperaceae (sedges) and Trachomitum, which are two taxa also associated to wetlands. One of the most interesting features of EDS8 is that it also contains regular high percentages of Artemisia (which includes wormwoods) in the lower part of the record, probably until the Early Holocene (although the exact timing of the Artemisia decrease needs to be better constrained with additional dating). High counts of Artemisia are interpreted as a more regional signal, reflecting cooler steppe conditions. The species identified in the pollen record at Fidan, within the organic layer preliminary dated to within the Late Glacial period, are comparable to the ones associated with modern times, with some variations in relative percentages. The Fidan pollen records also feature an increase in Artemisia during the Late Glacial, suggesting again cooler conditions during that time.

Geochemical variations in the EDSA cores, and especially in the calcium contents (measured by X-ray Fluorescence) also hint at a series of desiccation events that would have happened during the course of the Holocene. Although the time constraints for these events is still preliminary, and will have to be confirmed by additional radiocarbon dating, it seems that they may correspond at least partly to major drought events that can be recognized regionally or even globally.

The pollen data obtained at both the EDS and Fidan sites indicate no major local vegetation changes during the last c. 45-30,000 years in the arid and semi-arid Southern Levant. This is somehow different from the information derived from previous studies in the region, notably pollen data obtained from the Holocene Dead Sea. This can be explained by the Dead Sea’s larger catchment area than the EDS and Fidan wetlands, and records from this lake may reflect the regional rather than local evolution of environmental conditions. This means that to obtain the full picture of climate and environmental change for the late Pleistocene and Holocene in all its diversity, it is crucial to compare very local records to more regional studies. While more precise conclusions will only be drawn after additional dating has been obtained, results seem to point to cooler conditions during the Late Glacial period, followed by a warming trend during the Holocene, a time period which may also have been affected by desiccation events. Cooler conditions may have encouraged people to settle in arid lowlands, such as the Faynan area, during the Late Pleistocene.

This project is financed by the Swiss National Science Foundation, benefits from an affiliation with the CBRL, and is hosted by the University of Bern. Numerous people participated in this study; including, Jacqueline van Leeuwen (pollen identification and counting), Pim van der Knaap (plant identification), Erika Gobet (labwork and fieldwork), Eleni Asouti and Ceren Kabukcu (identification of charcoal and plant macrofossils), Carol Palmer (discovery of and fieldwork at the Fidan wetlands), Willi Tanner, Han van Dobben, Christoph Schwörer, Willy Tinner, Petra Boltshauser-Kaltenrieder, François Voisard (fieldwork), Fabrice Monna and Anne-Lise Develle (geochemistry).

Evaluating the Late Pleistocene Occupation of Wadi Faynan: A Report on the 2013 ‘Missing Links’ Field Season

Sam Smith (Oxford Brookes UniversityUK) and Russell Adams (University of Waterloo, Canada); emails: [email protected]; [email protected]

Roughly 20,000 years ago, during of the cold and dry conditions of the Last Glacial Maximum, the traditionally mobile, hunter-gatherer populations of South West Asia began to experiment with new ways of living. This period of social and economic experimentation, known archaeologically as the Epipalaeolithic, eventually led to what are perhaps the most significant economic and social transformations in human prehistory: the origins of agriculture and village life. Several decades of archaeological fieldwork in the Wadi Faynan, southern Jordan, have documented a range of spectacular sites belonging to these early agricultural communities (see, for example, CBRL Bulletin 2012, pages 64–67). However, their precursors have remained locally elusive and no definite Epipalaeolithic period sites have been identified in the Faynan. In order to fill this lacuna, the Missing Links project is evaluating a site in the starkly beautiful Barqa region of Faynan, aiming to identify and evaluate evidence for both Epipalaeolithic activity and Late Glacial palaeoenvironments. Our work will provide a long term context to the emergence of agriculture and village life in this area of southern Jordan. The Missing Links project is a collaborative initiative, involving archaeologists and geographers from the UK and Canada, and the 2013 fieldwork was funded by a CBRL Team-based Fieldwork Research Award.

The 2013 Field Season: First Results

The first season of fieldwork took place in May and June 2013 in the hot and arid Barqa. Our primary aims were to undertake archaeological survey and mapping to document and describe a scatter of artefacts, which were visible on the surface of the site, and also to attempt to understand the processes which had led to the site’s formation. The results here were remarkable—our initial pedestrian survey revealed that the artefact scatter covered an area in excess of 20,000 sq m and that the artefacts, which form a dense ‘pavement’, derive almost exclusively from the Epipalaeolithic period. Excitingly, we also identified clear differences in the types of stone tools across the site, suggesting that the scatter represented several cultural and chronological phases of the Epipalaeolithic. In addition to the scatter of stone artefacts, we also discovered possible evidence for stone architecture, in the form of limestone slabs protruding from the sand, and identified a low ‘mound’ where surface finds included burnt bone as well as Epipalaeolithic chipped stone.

General photograph of the Barqa region of Wadi Faynan (looking South). The light grey material lying on top of the sand is a ‘pavement’ almost exclusively comprised of Epipalaeolithic chipped stone artefacts

Close up photograph of the stone tool ‘pavement’ at Barqa showing dense concentration of Epipalaeolithic artefacts

The next stage of our fieldwork involved digging nine small (1 x 1 sq m) evaluation test pits to collect samples of stone tools, begin evaluation of the sub-surface archaeology of the site and explore the site’s geomorphological and palaeoenvironmental setting. In all but one of the test pits (Test Pit 8 was an exception) excavation revealed a similar stratigraphic sequence: the upper ˜50mm of each test pit contained extremely dense archaeology, in the form of chipped stone tools and tool making waste, which overlay a clean, largely archaeologically sterile windblown sand. This suggests that the site has formed as a result of deflation, where wind has blown away the original sediment matrix surrounding the artefacts, concentrating several episodes of Epipalaeolithic activity on the present day ground surface. Test Pit 8, located on the low mound where both stone tools and burnt bone were visible on the surface, told a different story. Here we found evidence for in situ, sub-surface Epipalaeolithic archaeology including a possible hearth, evidence for the manufacture of stone tools as well as signs of the consumption and butchery of a wide range of animals.

Analysis of the artefacts recovered during the 2013 fieldwork is ongoing. However, preliminary studies show that, in addition to more than 15,000 pieces of Epipalaeolithic chipped stone, we have animal bone (from Test Pit 8), shell (including dentalium) beads, ostrich egg shell, as well as two (broken) coarse stone mortars. Field analysis of the chipped stone artefacts will be key to identifying the precise cultural affinities of the Epipalaeolithic communities who inhabited the Barqa, but already our results suggest that several periods are represented. These include the hitherto elusive Natufian (˜15,000-12,000 cal BP), which is the immediate precursor to the Early Neolithic (11,600-10,200 cal BP) occupation of the region, as well as earlier Epipalaeolithic periods.

Summary & Plans for 2014

Overall, the first season of Missing Links fieldwork was highly successful. Taken together the quantity and variety of artefacts recovered from the site suggest that Barqa was the scene of significant human activity during the Epipalaeolithic period. This fills a major gap in our understanding of the prehistory of the Wadi Faynan and will allow us to better chart the long-term development of human communities in the area. However, several major research questions remain unanswered and addressing these will be the focus of our 2014 fieldwork campaign. Perhaps the most pressing issue involves understanding why the Barqa, which is presently arid, was attractive to Epipalaeolithic communities during the Late Pleistocene. Our working hypothesis here is that the Barqa was rather wetter during this period and we will evaluate this idea in 2014 through the excavation of several deep geomorphological test pits. A further aim is to undertake excavation of areas where we have identified the potential to discover in situ archaeology. These will include the limestone architecture revealed during our initial pedestrian survey and also expanded excavation in and around Test Pit 8 in order to collect material for scientific dating and explore the occupation horizons identified in 2013. Finally, we will complete detailed analyses of all artefacts recovered during the project. The ambitious aims for 2014 will be made possible by continued financial support from CBRL and also additional funding from both Oxford Brookes University and the Gerald Averay Wainwright Fund for Near Eastern Archaeology.

It is clear that the small scale Missing Links project will shed new light on the prehistory of Wadi Faynan, illustrating how much we still have to learn about the long term development of the region. It is also clear that now, perhaps more than ever, it is important to document the surviving archaeology, which faces growing threats from increasing development. Of particular concern here are plans for the construction of dams and barrages in the Faynan area (as reported in the Jordan Times 14th May 2014) meaning that, unless carefully managed, the globally significant archaeology of the region may be in jeopardy.

The Aerial Archaeology in Jordan (AAJ) Project, 2013

David Kennedy (University of Western Australia) and Robert Bewley (Heritage Lottery Fund), assisted by Rebecca Banks; email: [email protected]; [email protected]

The project conducted its 16th flying season in April 2013 to take advantage of the spring vegetation, a contrast to the dry autumn landscape of most previous seasons. The Royal Jordanian Air Force provided four flights totalling 21 hours; we recorded 920 sites on 7824 digital photographs; and all photographs can be seen in the Aerial Photographic Archive for Archaeology in the Middle East (APAAME) website: www.flickr.com/photos/apaame/collections.

Two flights were dedicated to the harra—the basalt lava field stretching across the panhandle and two others to the hinterland of Amman and Jarash. Although hundreds of sites of almost every period were recorded as part of AAJ’s continual capturing and monitoring of Jordan’s archaeological heritage, all four of the flights investigated specific sites or areas associated with current research both from within and outside the project. The AAJ project benefits immeasurably from the interest and expertise of colleagues who contribute information regarding new sites or sites where imagery needs to be updated.

Collaboration with AAJ

Berndt Mueller-Neuhof of the Deutsches Archäologisches Institut (DAI) accompanied one flight in the investigation of Bronze Age sites and flint mines in the panhandle and Ruwayshid area as part of the Northern Badia project (www.dainst.org/en/ project/badia-jordan). Reconnaissance of the Jebel Qurma region southeast of Azraq was conducted for Peter Akkermans of the Leiden University Jebel Qurma Archaeological Landscape Project (www.jebel-qurma.nl). Updated photography was taken of the many structures associated with Qasr Mushash for a project investigating ‘Water Management in Desert Regions’ at the DAI directed by Karin Bartl (www.dainst.org/en/project/qasr-mushash), and led to the identification of a hitherto unlocated small qasr between Mushash and Qasr Amra. Many structures identified by doctoral research at the University of Western Australia into the water supply of Jarash were investigated. This included photographs taken of an emergency excavation being conducted by the Department of Antiquities after illegal excavations of a mosaic were stumbled upon and reported in the course of ground survey.

The Hinterland of Roman Philadelphia

Sites associated with research into the Hinterland of Roman Philadelphia by Professor Kennedy were one of this season’s focuses. The almost unparalleled increase of population in Jordan over the last century has mostly been experienced in the north west of the country, especially the Belqa—the fertile region surrounding Amman—from Wadi Zarqa and highlands of Ajlun in the north to the plains of Madaba in the south. Sprawling urban centres have combined with massive development of the countryside to obscure, damage or destroy the ancient landscape.

Nineteenth-century travellers and early archaeological expeditions give some indication of the wealth of material that has now become hidden. Investigation of archives such as those of Brünnow and von Domaszewski (Princeton University), published diaries of travellers digitized by programmes such as Google Books, Hathi Trust and Archive.org, and historical maps has allowed the location of many sites previously unknown or lost. Further investigation through the use of historical imagery, digital satellite imagery made available through free interfaces such as Google Earth and Bing Maps, and lastly through AAJ’s flying program allows for this information to be verified and expanded upon.

The two flights over Amman’s hinterland had varied results. Some sites were completely overlain by modern settlement where traces of the pre-modern could only be discerned in the adaptation of building materials, abandoned walls, and repurposed tombs and water structures. Other sites were found purely by chance: when flying over Umm el-Hannafish, a previously unreported Roman road was identified in the Spring grass, with a follow up ground visit confirming the identification.

Qasr el-Muwaqqar

Qasr el-Muwaqqar, located to the southeast of Amman on a ridge overlooking the fertile plain to the west and desert to the east, was a site that yielded unexpected results. The intention was to take updated photographs of the main two structures; the Qasr (fort, castle or palace) and the large reservoir next to the highway to Azraq, and to investigate the possible location of a second reservoir as mentioned in historical travellers’ accounts and partially visible in historical aerial photographs. We were not overly hopeful that the site could be identified because the Qasr is almost hidden and partially overlaid by the village around it which did not bode well for any other structures in the vicinity of the growing modern town. Recent nearby excavations of a building with mosaics allowed us not only to capture a previously unreported site however, but it had also exposed one of the walls of the reservoir we sought which apparently had been overlooked by the excavation. A follow up ground visit showed that the reservoir had its lining still intact and that the mosaic building was only partially excavated and likely related to other structures mentioned in historical accounts. Preliminary results combining the varied sources of data were presented at a seminar in Oxford.

The excavated building with mosaics at Muwaqqar. The wall of the reservoir can be seen to the left amongst spoil (APAAME_20130414_DLK-0013)

AAJ remains the only dedicated aerial archaeology programme in the Middle East. The investigation into the archaeological heritage of Jordan using aerial imagery continues to yield important results not least by monitoring threatened sites and alerting the authorities to endangerment.

AAJ’s current flying programme is funded by the generous support of the Packard Humanities Institute. With special thanks to Mat Dalton, Don Boyer and Nadja Qaisi.

Other research in progress on this theme 2013/14:

Shimon Gibson (University of the Holy Land, Jerusalem) The Sataf Project of Landscape Archaeology in the Judaean Hills (1987–89) (Project Completion Award)