When we planned to dedicate part of this December issue to risk communication in epidemics and emerging disease outbreaks, we did not know this would coincide with the Ebola crisis that has been so devastating for many countries in West Africa. Yet we knew how increasingly important this topic is – given that we are always at risk for a new disease outbreak or epidemic in some part of the world. We also knew that one of the key features of the twenty-first century, increased mobility and travel, is what makes virtually any communicable disease just one flight away from us all. We learned it during SARSCitation1 and the H1N1 pandemic,Citation2 and via the many other disease outbreaksCitation3 we can recall in different countries and settings over the last few decades. We also knew that because of weak health systems, vulnerable and underserved populations are always at the greatest risk of paying a high price as the result of epidemics and disease outbreaks – both in terms of the loss of human lives as well as further delays in socio-economic development, which inevitably follow events of the proportions of Ebola.

So, why don't funding priorities privilege risk communication preparedness and provide global and local communities with the tools, training, and resources they need for a swift response? At the same time, how can we expect people to suddenly change social norms and customs they have been practicing for generations, or embrace difficult emergency behaviors such as quarantine, or know what to do in the case of a public health emergency of any kind if we have not previously prepared them? Yes, in most developing countries, there are too many tough and conflicting priorities and the choice is often between treating an HIV/AIDS or malaria patient today or preventing and preparing for a potential disease of tomorrow. Yes, because of our own optimistic human nature we often feel that disasters have a low chance of occurring. But history has proven us wrong time and again, and the Ebola crisis has further strengthened the case for heightened investment and preparedness on risk communication and other disease control measures. I feel that one way to honor the many lives that have been lost to Ebola is to seize the opportunity this crisis has provided our global health and social development communities to unite in advocating across our professions and organizations for increased training, funding, research, and preparedness on risk communication and other disease mitigation measures both at the global, community, and local levels.

For while now, ‘risk communication’ has emerged as an important component of disease outbreak preparedness and control as there is ‘a significant communication demand in identifying serious health risks such as potential epidemics, … preparing at-risk publics to confront health risks, and coordinating responses when these serious health crises occur’.Citation4,Citation5 Central to health risk communication is the role of communities and their members in addressing existing obstacles, barriers, and social norms that may jeopardize the adoption and sustainability of disease mitigation measures and behaviors.Citation6 With its emphasis on social and behavioral results, risk communication is actually a system-changing strategy that may have long-lasting impact on different institutions, key players, and levels of society. One of the many arguments for an increased investment in risk communication preparedness at the global, community, and local levels is the potential for well-designed and executed health risk communication interventions to strengthen health and social systems by removing barriers to outbreak response but also to overall disease prevention and treatment.

If we play this right, one of the legacies of Ebola could be stronger health systems that would emerge strengthened by community participation, resilience, and entrepreneurship. This could be achieved by showing people that they can indeed work across sectors; that communities have relevant expertize and much-needed cultural competence to develop communication strategies, media, and activities and engage their own people; and that the role of teachers, religious leaders, mothers, business owners, community health workers, and citizens can indeed be expanded to include much-needed skills and confidence to effectively address key issues in epidemics and emerging disease outbreaks. As someone who, among many others,Citation3,Citation6–Citation12 has always advocated for a community-centered approach to risk communication and the development and training of local capacity and social mobilization/community engagement partners, I am glad to see that many voices are joining in contributing to progress toward a participatory and integrated approach to risk communication. Such approach would be also instrumental in advocating for and facilitating the many other changes in terms of policies and health and social services that health systems need to not only be prepared to address epidemics and disease outbreaks but also to deal with chronic diseases, maternal and child mortality, and many other health and social issues of our times.

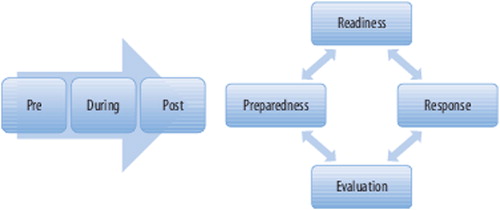

Yet for this vision to succeed, we need resources. We need the commitment of wealthy governments and key funders. We need to help build the capacity of community partners and local governments on key models, principles and strategies of communication planning, implementation and evaluation, disease mitigation measures, multisectoral partnerships, strategic and participatory planning, citizen and community engagement, as well as skills to communicate clearly and about uncertainties, and to deal with people's psychological response to crisis. Most importantly, we need a new mindset that is centered on social and behavioral change and global to local coordination,Citation3 so that we can effectively help at-risk communities and make sure they are clear about everyone's roles and key behavioral and social results to be achieved. One that will make sure we think of epidemics and disease outbreaks as being always on the verge of happening. One that will allow us to move from a ‘disaster rut’ to the ‘Preparedness-Readiness-Response-Evaluation-Constant Cycle’,Citation6 so we can adopt a systematic and coordinated approach to incorporating lessons learned in our thinking and actions ().Citation6,Citation12

Figure 1. Moving from the pre-during-post scenario to the preparedness-readiness-response-evaluation constant cycle (PRRECC). Source: Schiavo R. Health communication: from theory to practice. 2nd ed. Fig. 6.5. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, an imprint of Wiley; 2013, p. 212–6. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

While we celebrate some good victories (WHO declared Nigeria Ebola-free on Oct. 20),Citation13,Citation14 the global response continues to be tested across different communities and country settings despite the incredible work, commitment, and personal sacrifice of health workers, most affected communities, and colleagues from many different organizations. It is time to get busy and join across organizations and sectors to make sure our current and future investment in preparedness is adequately funded and prioritized.

About this December issue

Over the last few months, we have established many new sections for the Journal that allow it to harness its role in contributing to global conversations at the intersection of health communication, healthcare, global health, and social development. We are honored to include in our special themed section, which is dedicated to risk communication in Ebola and other epidemics and emerging disease outbreaks, so many authoritative opinions, interviews, and perspectives on different aspects of the Ebola crisis and risk communication. I want to thank the colleagues from USAID, World Health Organization, Columbia University, and other international organizations and experts for committing the time to provide their perspectives or coordinate their organization's contribution to this issue of the Journal. Also, thanks to JCIH's Editorial Assistant, Radhika Ramesh, for her great work on the interviews and overall help. Through the Guest Editorial, three Interviews, and Letter we publish in this issue, we hope to provide our readers with a much closer picture of key issues and strategies from the frontline of the Ebola crisis as well as important reflections and perspectives on the history and potential future of risk communication and disease outbreak control.

Of equal importance and great interest are the many topics covered in the Papers section of this issue, which provide useful new evidence, models, lessons learned, and/or insights on timely topics including the potential role and design of health information technologies for patient-centered communication and care; parental acceptance of adolescent immunization in underserved communities and implications for communication interventions; and the use of photovoice to engage adolescents around personal dietary and physical activity influences and behaviors.

Happy Holidays from us all at the Journal of Communication in Healthcare: Strategies, Media, and Engagement in Global Health! Thanks for your many contributions and readership in 2014!

Acknowledgement

The author wishes to thank Seth Schwartz from Jossey-Bass/Wiley for his assistance with the inclusion of the figure/model featured in this editorial, which is used by permission.

References

- Abraham T. Twenty-first century plague: the story of SARS. Hong Kong University Press; 2004, 2005, 2007.

- World Health Organization. What is the pandemic (H1N1) 2009 virus? World Health Organization, Global Alert and Response (GAR). February 24, 2010 [retrieved 2014 October]. Available from: http://www.who.int/csr/disease/swineflu/frequently_asked_questions/about_disease/en/.

- Schiavo R. Mapping & review of existing guidance and plans for community- and household-based communication to prepare and respond to pandemic flu. Research report. A report to UNICEF. New York, NY: UNICEF; January 2009. [retrieved 2014 October]. Available from: http://www.unicef.org/influenzaresources/index_1072.html.

- Kreps G. Health communication theory. In: Littlejohn S, Foss K, (eds.) Encyclopedia of communication theory. A SAGE Reference Publication, SAGE; 2009. p. 464–9.

- Schiavo R, Leung MM, Brown M. Communicating risk and promoting disease mitigation measures in epidemics and emerging disease settings. Pathog Global Health 2014;108(2):76–94.

- Schiavo R. Health communication: from theory to practice. 2nd ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, an Imprint of Wiley; 2013.

- Chitnis K. Risk communication and emerging infectious diseases: lessons and implications for theory–praxis from avian influenza control. In: Obregon R, Waisbord S, (eds.) The handbook of global health communication. UK: John Wiley & Sons; 2012.

- Schoch-Spana M, Franco C, Nuzzo JB, Usenza C. Community engagement: leadership tool for catastrophic health events. Biosecur Bioterror 2007;5(1).

- World Health Organization. Communication for behavioural impact (COMBI): a toolkit for behavioural and social communication in outbreak response. 2012 [retrieved 2014 October]. Available from: http://www.who.int/ihr/publications/combi_toolkit_outbreaks/en/

- UNICEF. UNICEF communication for development support to public health preparedness and disaster risk reduction in East Asia and the Pacific: a review. UNICEF East Asia and Pacific Regional Office, July 2013 [retrieved 2014 October]. Available from: http://www.unicef.org/cbsc/files/Communicatiln_for_development_support_to_public_health_preparedness.pdf.

- Chatigny E. Public involvement at the Public Health Agency of Canada. In: Citizen engagement in emergency planning for a flu pandemic. Presentation at: the National Academies Disaster Roundtable, Washington, DC; October 23, 2006.

- Schiavo R. Public health communications: conceptual frameworks and models relevant to public health emergencies, in World Health Organization, Social mobilization in public health emergencies: preparedness, readiness and response. Report of an informal consultation, 2009 December 10–11, World Health Organization, Geneva, CH. World Health Organization; 2010.

- Cumming-Bruce N. Nigeria is free of Ebola, health agency affirms. The New York Times, October 20, 2014 [retrieved 2014 October]. Available from: http://www.nytimes.com/2014/10/21/world/africa/who-declares-nigeria-free-of-ebola.html?_r=0.

- World Health Organization. WHO declared end of Ebola outbreak in Nigeria. World Health Organization, Global Alert and Response (GAR). October 20, 2014 [retrieved 2014 October]. Available from: http://www.who.int/csr/disease/ebola/en/