I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I die, discover that I had not lived.

Henry David Thoreau, 1854 Walden

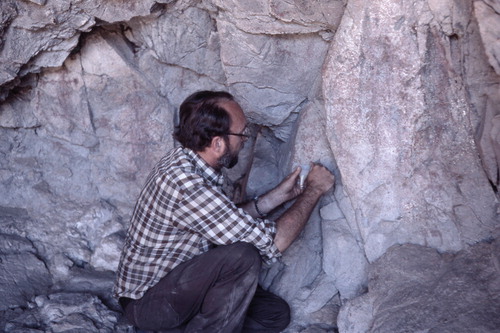

Sam Payen collecting pigment.

The quote from Thoreau epitomizes the archaeological adventures of the late Sam Payen, a man in quest of knowledge about the past in the woods, in the valleys, and in the desert; an understanding of bygone cultures to be passed on to his colleagues and the public at large.

Louis A. Payen (Jr.) was born in Sacramento on January 30, 1940, and died in Sloughhouse on November 25, 2013, from complications of prostate cancer. According to his wife Pam, Sam fortunately died relatively quickly without much suffering. His parents were both veterinarians and his father's side of the family was of pioneer California stock. Sam's great-grandfather, Louis Payen, was born near Paris, France, in 1834. He came to San Francisco in 1854 by way of the Cape Horn route. He mined in El Dorado County, prejudice subsequently driving him from the mines, and he worked as a chef in several Sacramento restaurants. In 1882, he opened a large popular French restaurant in the same city. After retiring from the restaurant business, he bought the original Herman D. Barton 1,120-acre ranch south of Folsom. Sam (or Sammy to his family and friends from his youth) was raised in a cattle ranching lifestyle, one that he came back to in his later years, but never really left.

Sam's early curiosity about archaeology likely was derived from his father's own interest in Native American Indian culture and their evidence present on family ranches near Sloughhouse, Stampede Valley, and Sierra Valley in northern California. At Sacramento High School, he joined a junior group of the Sacramento Mineral Society and even at first wanted to have a career in art. One of his early vehicles he painted with a dragon and flames. I would suppose that this initial interest in Native American Indian culture, art, and his historic California roots was parlayed into his remarkable archaeology career where, among many achievements, his scientific illustrations and study of American Indian rock art are noteworthy (e.g., Olsen and Payen Citation1968; Payen Citation1959, Citation1966; Payen and Boloyan Citation1963; Ritter et al. Citation1982).Footnote1

Sam's formal introduction to archaeology happened while he was still in high school when it is likely that his father—who knew the influential and renowned archaeologist Francis “Fritz” Riddell, the then curator of the California State Indian Museum in Sacramento—got them together. Here Sam tied in with another then novice archaeologist Ric Windmiller and good friend, archaeologist Norman Wilson. There followed participation in digs at Sutter's Fort, Mustang (CA-YOL-13), Wheatland (CA-SUT-21), and CA-SUT-22 near Nicholas (also with Don Jewell of American River College and John S. Clemmer), and elsewhere. The work at Sutter's Fort led to his first publication in historical archaeology at age 21 (Payen Citation1961a). It is through this connection with Riddell and his association with Robert F. Heizer at the University of California, Berkeley, that Sam published his ongoing rock art studies (as listed above) while still a teenager.

After becoming involved in archaeology at a professional level, Sam continued his education at Sacramento State College (now University) finishing his Bachelor's and Master's degrees. As related to me by one of his college friends and now-retired archaeologist Jerald (Jerry) Johnson, in grammar school in the sixth grade a teacher said he would never go to college. This inspired Sam and he proved her wrong, although she died in the interim and he was never able to show her his achievements! Johnson wrote a 2014 obituary for Sam in the Newsletter of the Mother Lode Grotto of the National Speleological Society.

Sam was influenced at Sacramento State in the early years of their anthropology program by William Beeson, a Southwesterner, and geographer and archaeologist Brigham Arnold, who offered him an “environmental-geomorphology” perspective. I will bet Richard Reeve—of the department with roots at Sacramento Junior College where central California archaeology excavations were very early practiced by Heizer, Franklin Fenenga, the Riddell brothers, and others—also had some stimulus. He was also heavily inspired by the post-WWII Berkeley archaeologists, including James Bennyhoff, Riddell, and later Martin Baumhoff as discussed below. The Sacramento State guidance also included later co-worker, co-author, and friend William H. “Ole” Olsen as well as fellow students.

During his days at Sacramento State (and even prior), Sam traipsed all over the Sierra Nevada recording petroglyphs and pictographs, sometimes with Ric Windmiller, additional times with Jerry Johnson and others. The multidimensional documentation included not only Sam's artistic renditions but also innovative photography including strobe and Coleman lantern side-lighting at night for better image clarity. Carrying such equipment into and out of the wilderness at night was no small task. He was kind enough during this period to guide my father, Dale Ritter, an avocational rock art researcher, to some of his known sites. Sam even recreated a striking painting of pictographs from the Sierra using natural pigments from the area, a painting that was mounted for display for a time at Sacramento State. Jerry indicated that he and Sam went all over the place in their explorations, especially since Sam's dad had his own gas pump. He indicated to me that Sam was always ready to take on the spur of the moment trips to archaeology sites and share his already considerable wealth of information, including trips to the far reaches of northwestern California and northeastern Nevada. Sam never gave up on a vehicle and one of his first was an old Chevy pickup with a granny gear taking him to places even a four-wheel drive vehicle would have trouble.

Of course, Sam had an enduring interest in Native American Indian lifeways and culture. His parents and he, an only child, knew many Indian people through veterinary and ranch work. One who lived on the ranch was “Walnut George.” Young Payen completed a manuscript (Payen Citation1961b) on the Walltown Nisenan and maintained a lifetime interest in their culture, especially in the documentation of traditional pre-European culture, a vestige of the Alfred Kroeber “salvage ethnography” approach. Sam attended many of the traditional or neo-traditional ceremonies such as the Hoopa White Deerskin Dance, the Maidu Bear Dance, and Pomo Big Head dances in the Clear Lake area. According to Olsen, one time Sam and David Boloyan, an early co-author and fellow student, went to the Clear Lake area of Lake County to buy Pomo baskets (Sam knew his California baskets). During participation in hand games, they virtually lost their shirts. Sam did not involve himself in the politics of archaeology nor California Indian activism as he was a friend to many and worked with tribal folk on numerous occasions on projects where there was a joint effort in respecting and discovering the past.

Sam was tough with calloused hands from ranch work. On one occasion when working with Johnson on the Camanche Reservoir project driving a haul road that crossed a relatively deep creek, the four-wheel drive vehicle—not in four-wheel drive—encountered slick cobbles and door-deep water and would not proceed further. In those days you needed to turn the WARN hubs on the front wheels before engaging the four-wheel drive. Sam exited the window and dove under the water and turned them, no problem, and off they went. Sam was an excellent mechanic and in his vehicles he carried an old canvas bag full of nuts, bolts, screws, and the like picked up on the road and elsewhere, just in case. And they came in handy on occasion on various expeditions we enjoyed.

A number of the early Sac State archaeology students like Sam were spelunkers or cavers exploring the Sierra Nevada caves, including mortuary caves such as Pinnacle Point Cave in Tuolumne County. He completed an article on pipes from the cave and an unpublished manuscript on the snail shell fauna in the cave (Payen Citation1964, Citation1965) in addition to working on his Master's degree. Just before he died, he and Johnson were collaborating on finishing a more complete study of this cave. Sam was also instrumental in the study of limestone caves in the McCloud River area of Shasta County, including Potter Creek and Samwell. One of his notable discoveries was an atlatl with pointed foreshafts from Potter Creek Cave (Payen Citation1970).

Sam was caught up in the data recovery efforts of the 1960s brought on by the proliferation of major federal, state, and local infrastructure projects such as the San Luis, Little Panoche, New Melones, Oroville, and Camanche reservoir developments. He was employed by the California Division of Beaches and Parks (now Parks and Recreation) under Riddell and Olsen. In this position, he led digs, performed lab work, and wrote reports, eventually leaving a full-time position for the Ph.D. program. He was also an active member in the Central California Archaeological Foundation, the first cultural resource management group in California where projects were funded and run, symposia sponsored, and colleagues from the central and north state gathered to exchange ideas and information. These were dramatic days even before the founding of the Society for California Archaeology whereby regional academic, private, and government archaeologists and students came together for the purpose of improving and promoting archaeology education, research, and coordination.

Sam had an interest in desert archaeology, in northwestern Nevada, northeastern California, and Baja California. In 1969, we journeyed out to visit the dissertation work of David H. Thomas in central Nevada, a trip that witnessed innovative archaeology and scientific achievement, returning to California just in time to see the black and white televised landing on the moon. With Sam's good sense of humor, he would laugh at the thought that the moon location is now an archaeological site. His ranching background and the fact that his father was a large-animal veterinarian led Sam to write an article on farriery and other horse trappings found at two ethnohistoric Shoshoni villages (Payen Citation1978).

Sam began the Ph.D. program at the University of California, Davis, under Riddell's Berkeley colleagues Martin Baumhoff and David Olmsted, and participated in archaeology field classes in Lassen County (Lorenzen site) and in Nevada (Bare Cave). He soon switched from Davis and the thought of a dissertation on California cave archaeology to the University of California, Riverside (UCR), where he was influenced by R. Ervin Taylor, Sylvia Broadbent, and others. His fellow students and co-workers included Robert Bettinger, Meg McDonald, Christine Prior, Carol Rector, Peter Slota Jr., Philip Wilke, and additional folk.

His dissertation (Payen Citation1982) focused on the pre-Clovis of North America, especially some of the early purported flaked stone industries. He was employed at the radiocarbon lab at UCR and published a number of articles with other scholars on dating issues related to early human presence in the American West and further topics. This interest in early flaked stone industries was developed from his prior examinations of possible late Pleistocene-early Holocene flaked stone assemblages in drainages along the east side of the Sacramento-San Joaquin Valley (cf. Ritter et al. Citation1976). Coupled with his interest in initial human presence in the New World were his background in physical geography/geomorphology (remembering Arnold's influence) and his membership in the American Quaternary Association (AMQUA).

During the 1970s and into the mid-1990s, Sam accompanied this writer and others, including Carol Rector, on formal and informal research expeditions to various locations within Baja California. This resulted in eight publications where he was a co-author regarding the rock art and other prehistoric site distribution patterns, mostly in the central part of the peninsula. Sam was particularly intrigued with the various missions we visited. On one occasion in the peninsula, we met up with anthropologists Richard and Shelagh Brooks and Don Tuohy and helped with their University of Nevada, Las Vegas, archaeology field class.

These adventures covered many miles in Sam's beloved 1973 red Toyota Land Cruiser that probably is still sitting at the ranch. We forded the flooded Río Rosario, inadvertently (or maybe on purpose?) drove through checkpoints with armed men, slept on the ground, endured desert heat and wind, kept scorpion stings to a minimum, bathed every week or so whether indispensable or not; witnessed outstanding, unspoiled archaeology and roads that were not really there. I don't remember Sam ever falling asleep at the wheel but the narrow highway and big rigs would keep anyone awake. Sam enjoyed seafood, burritos, spaghetti, stew, Kool-Aid, and pudding among other field delights. He was notorious for eating his peanut butter and jelly sandwiches and cookies and living a bit like a pauper, which he wasn't. He seemed to always wear Levi's and a cowboy shirt, and sometimes when the wind didn't blow too hard his straw cowboy hat. I think I saw him dressed up once, so it was possible.

In talking with some of his friends, we agree that he was a very private person, a meticulous, hard-working researcher, singularly focused, well-prepared, concerned with accuracy and relevance. Some of his personality undoubtedly was derived from his conservative ranch family background. He wanted to do his own thing if it interested him. He would see the discipline (or world) of archaeology as more than just things in the ground. Only on rare occasions did he imbibe in the juice too much. While he liked kids he had none of his own but a stepson through his wife. As Ric Windmiller stated to me, he was a first-rate field man, and that observation is shared by his colleagues. He learned his craft from a generation of archaeologists who did not have computers and relied on brain power and books and articles. Sam was a bibliophile and spent many hours scanning rare and used book catalogues and seeking out used book stores to augment his extensive library. As Carol Rector related to me, “He often enriched his articles with obscure references that had not been used in the literature before. He kept all this information in his head and he was happy to help others locate information on whatever they were working on.” If we must cast labels, we could call him Old School. But there is nothing wrong with that!

Sam was not very comfortable speaking to classes or audiences, but he educated many of us by his good example and findings. Realizing difficulty in landing an academic or museum job and needing to help his elderly father with the family cattle ranches, Sam married his cowgirl, Pam, and for the most part left archaeology in the 1990s. He worked on the occasional project in the Sierra until his health would not allow it. In 1995, for instance, he conducted excavations at CA-SIE-1059, the Old Webber Gravel Pit Site, and assisted Ric Windmiller's consulting firm on a few projects.

In The Issa Valley, Czeslaw Milosz (2000) wrote that “The living owe it to those who no longer speak to tell their story for them.” I can hardly do Sam justice in this short work but hope that I have captured some of the flavor of his life, contributions, and interests. Inputs to this memorial came from Jerald Johnson, Philip Wilke, William H. Olsen, Pamela Payen, Carol Rector, Kathy West, and Ric Windmiller. I appreciate their responses and hope I have encapsulated their comments correctly.

Notes

1 An obituary on Louis A. Payen with a complete bibliography was written by Dr. Philip Wilke for the Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology (Vol. 34, No. 2, 2014). Other than those publication outlets listed here, Sam Payen's works can be found in Science, Nature, Radiocarbon, Journal of California Anthropology, Journal of Caves and Karst Studies, Historical Archaeology, Journal of Forensic Science, Pacific Coast Archaeological Society Quarterly, and publications in books and monographs from Ballena Press, Greenwood Press, Academic Press, San Diego Museum, Sacramento Anthropological Society, and others.

References Cited

- Olsen, William H., and Louis A. Payen 1968 Archaeology of the Little Panoche Reservoir, Fresno County. Department of Parks and Recreation, Archeological Report No. 11, Sacramento.

- Payen, Louis A. 1959 Petroglyphs of Sacramento and Adjoining Counties. University of California Archaeological Survey Reports 48:66–92. Berkeley.

- Payen, Louis A. 1961a Excavations at Sutter's Fort, 1960. Division of Beaches and Parks, Archeological Report No. 3, Sacramento.

- Payen, Louis A. 1961b The Walltown Nisenan. Manuscript on file at the Department of Anthropology, California State University, Sacramento.

- Payen, Louis A. 1964 “Pipe” Artifacts from Sierra Nevada Mortuary Caves. Cave Notes 6:25–32.

- Payen, Louis A. 1965 Preliminary Report on the Archaeological Investigation of Pinnacle Point Cave, Tuolumne County. Manuscript on file with the Department of Anthropology, California State University, Sacramento.

- Payen, Louis A. 1966 Prehistoric Rock Art of the Northern Sierra Nevada. Unpublished Master's thesis, Department of Anthropology, Sacramento State College, Sacramento.

- Payen, Louis A. 1970 A Spearthrower (Atlatl) from Potter Creek Cave, Shasta County, California. In Papers on California and Great Basin Prehistory, edited by Eric W. Ritter, Peter D. Schulz, and Robert Kautz, pp. 155–170. Center for Archaeological Research at Davis, Publication No. 2. University of California, Davis.

- Payen, Louis A. 1978 Smoothshod-Roughshod, an Analysis of the Farriery and Other Horse Equipment from Two Historic Shoshoni Village Sites in Grass Valley, Nevada. In History and Prehistory at Grass Valley, Nevada, edited by C. William Clewlow, Jr., Helen Fairman Wells, and Richard D. Ambro, pp. 85–103. University of California, Institute of Archaeology, Monograph VII, Los Angeles.

- Payen, Louis A. 1982 The Pre-Clovis of North America: Temporal and Artifactual Evidence. Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, Department of Anthropology, University of California, Riverside.

- Payen, Louis A., and David S. Boloyan 1963 “Tco'se,” an Archaeological Study of the Bedrock Mortar-Petroglyph at AMA-14, near Volcano, California. State of California, Division of Beaches and Parks, Archeological Report No. 8, Sacramento.

- Ritter, Eric W., Brian W. Hatoff, and Louis A. Payen 1976 Chronology of the Farmington Complex. American Antiquity 41:334–341.

- Ritter, Eric W., Carol H. Rector, and Louis A. Payen 1982 Marine, Terrestrial and Geometric Representations within the Rock Art of the Concepción Peninsula, Baja California Sur. In American Indian Rock Art 7–8, edited by Frank G. Bock, pp. 38–56. American Rock Art Research Association, El Toro, California.