Abstract

Background:

Carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae (CPE) are emerging worldwide, representing a major threat for public health. Early CPE detection is crucial in order to prevent infections and the development of reservoirs/outbreaks in hospitals. In 2008, most of the CPE strains reported in Belgium were imported from patients repatriated from abroad. Actually, this is no longer the case.

Objectives and methods:

A surveillance was set up in Belgian hospitals (2012) in order to explore the epidemiology and determinants of CPE, including the link with international travel/hospitalization. The present article describes travel-related CPE reported in Belgium. Different other potential sources for importation of CPE are discussed.

Results:

Only 12% of all CPE cases reported in Belgium (2012–2013) were travel related (with/without hospitalization). This is undoubtedly an underestimation (missing travel data: 36%), considering the increasing tourism, the immigration from endemic countries, the growing number of foreign patients using scheduled medical care in Belgium, and the medical repatriations from foreign hospitals. The free movement of persons and services (European Union) contributes to an increase in foreign healthcare workers (HCW) in Belgian hospitals. Residents from nursing homes located at the country borders can be another potential source of dissemination of CPE between countries. Moreover, the high population density in Belgium can increase the risk for CPE-dissemination. Urban areas in Belgium may cumulate these potential risk factors for import/dissemination of CPE.

Conclusions:

Ideally, travel history data should be obtained from hospital hygiene teams, not from the microbiological laboratory. Patients who received medical care abroad (whatever the country) should be screened for CPE at admission.

Introduction

Carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae (CPE) were first reported in the early nineties and have been since documented worldwide. They represent a major public threat in all human healthcare settings (acute and chronic care sectors), including the community. Carbapenemase production in bacterial pathogens jeopardizes the successful treatment of severe infections, often implicating multidrug-resistant strains such as extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae (ESBLE). Since carbapenemase resistance determinants are located on mobile genetic elements (plasmids, transposons), often in association with resistance to several other classes of antimicrobials, very few drugs (colistin, tigecycline, high dose of carbapenem) remain active against these isolates and can be used therapeutically for the treatment of systemic infections. The fact that carbapenemase coding resistance genes are easily transferable through plasmids from one bacteria to another also explains the rapid diffusion of these resistance mechanisms amongst the intestinal microbiota.Citation1

Detection of carbapenemases in the microbiology laboratory is complex because the level of expression can be variable, sometimes leading to very discrete decrease in carbapenem susceptibility, and it mostly relies on phenotypic methods (by carbapenemem hydrolysis detected by colorimetric tests, e.g. Carba NP test, or by mass shift following hydrolysis of the beta-lactam ring, which can be detected by Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight Mass Spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS). However, characterization of the precise type of carbapenemase involved (which is mostly required for epidemiological purposes) can currently only be achieved by the use of molecular tests. The latter are not universally available in diagnostic laboratories. Yet, early identification of hospitalized patients colonized or infected with CPE is crucial in order to prescribe timely and appropriate antimicrobial treatment for CPE-infections and for containing the nosocomial transmission and the subsequent growing reservoirs of CPE in healthcare settings and in the community. Prior to 2011, the number of reported episodes of CPE infection in Belgium was very scarce, and it almost exclusively concerned patients who had undergone sanitary repatriation from foreign countries.Citation2–Citation5 The ever increasing population mobility increases the risk for import and dissemination of CPE in Belgian healthcare settings via persons who travelled abroad with or without hospitalization during their stay.

From 2011 onwards, Belgian hospital laboratories voluntarily shipped a rapidly growing number of carbapenem non-susceptible (CNSE) Enterobacteriaceae isolates to the National Reference Center (NRC) in order to identify the resistance mechanisms and to confirm carbapenemase production. Many of these cases were no longer related to travel abroad nor healthcare associated, thereby suggesting the rapid autochthonous spread of CPE strains in Belgium.Citation6 Nevertheless, we should remain alert with respect to the potential importance of travellers as an at risk group as demonstrated by the results of the recent VOYAG-R study.Citation7 Between February 2012 and March 2013, the authors of this study examined the risk factors for acquisition of CPE and ESBLE among 574 travellers, back from travel in a foreign country (America: n = 183 travellers, Africa: n = 195, and the Middle East and Southeast Asia: n = 196, including 57 having travelled in India). Travellers who visited these continents presented an increased risk for acquisition of CPE if they had been hospitalized during their stay or, in case of a sanitary repatriation, even if they did not have direct contact with healthcare structures in these regions.

CPE was identified among 3 out of 57 (5%) tourists, back in France after having visited India (two OXA-181 [mutant of OXA-48 typically found in CPE isolates from the Indian subcontinent. OXA-181 is very often present in association with NDM carbapenemase] and one New Delhi metallo-beta-lactamase 1 (NDM-1) producing E. coli). None of these patients have had contacts with healthcare during their stay in India. Follow-up cultures obtained from these three travellers after their return in France showed that the duration of CPE carriage was relatively short (up to 3 months).

Probably, poor hygiene and sanitary conditions (contamination of the environment and/or food and water supplies) and an uncontrolled antimicrobial use in India could count as risk factors for CPE and ESBLE acquisition at the time of a travel in this country.

For ESBLE, the link with travel abroad has been establishedCitation8–Citation12 for a long time. In these studies, the percentage of subjects who developed EBLSE carriage during travel ranged from 5 to 85%, depending on the countries visited.Citation9–Citation12 One study performed in Sweden11 showed that ESBLE acquisition was frequent (30% of the travellers) after international travel and that the continent visited accounted as the most important risk factor for ESBLE colonization; travel to the Indian subcontinent being associated with the highest risk for ESBLE acquisition (71.4% of the visitors to India (odds ratio (OR) 24.8, P < 0.001), followed by a travel to Asia (India not included) (44.8%, OR 8.63, P < 0.001) and Northern Africa (43.3%, OR 4.94, P = 0.002). These findings globally match with those from other studies.Citation9,Citation10,Citation12–Citation15 Other risk factors for travel-related ESBLE acquisition were the occurrence of diarrhoea or other digestive symptoms during stay, as well as the traveller's age, patients above 65 years presenting the highest risk of acquisition. In the Swedish study, no CPE acquisition was found, but the methodology used for screening focused on detection of cephalosporin resistance among Enterobacteriaceae. Therefore, the presence of carbapenemases could have been underestimated. According to recent literature, the duration of ESBLE carriage can be long with 18% of the travellers still asymptomatic carriers 6 months after acquisition.Citation12

Imported CPE and other multidrug-resistant organisms (MDROs) following travel are not only involved in epidemics but can also lead to severe, potentially lethal infections.Citation16

Material and Methods

In January 2012, a centralized prospective CPE-surveillance network was set up in Belgium, inviting all laboratories (hospital and private) to submit all suspect CNSE strains isolated from screening and from clinical samples to the NRC. The surveillance aimed to explore the emergence of CPE in Belgium and to describe the microbiological and epidemiological characteristics and determinants, including the link with international travel. The different aspects of travel-associated CPE in Belgium are described and discussed in the present article.

A suspect CPE isolate was defined as an Enterobacteriaceae strain (especially Klebsiella pneumoniae, Escherichia coli, and Enterobacter cloacae) not susceptible to meropenem according to the specific EUCAST [The European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing; http://www.eucast.org/clinical_breakpoints/] or CLSI [Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; http://clsi.org/] clinical breakpoints. Laboratories were also encouraged to test the in vitro susceptibility to other carbapenem compounds (e.g. ertapenem) in order to increase the sensitivity of detection of CPE in line with EUCAST and CLSI guidelines. The epidemiological surveillance (WIV-ISP) included data from all confirmed CPE-positive cases (confirmed by the NRC) as well as those from fully investigated CPE-outbreak episodes (during which all consecutive CPE strains were not systematically referred for confirmation to the NRC). The collected epidemiological and microbiological data were gender, birth year, and hospitalization status (inpatient or outpatient), and admission date and hospital ward – for inpatients, colonization or infection (presence of clinical signs of infection) – infection status, bacterial species and carbapenemase types, sporadic versus epidemic context of the case, date of sampling, anatomical site and sampling context (clinical or screening sample), clinical patient data, antecedents such as a recent stay (last 12♣months) in a Belgian hospital or in an nursing home, transfer from or recent stay (within the last 12 months) in a foreign hospital (and visited country), and present or past antimicrobial treatment (within the last 3 months). Duplicates were excluded; for patients with consecutive isolates harbouring the same carbapenemase, only data from the earliest notification were included in the surveillance.

Results

Since the start of the active CPE-surveillance programme in Belgium, 890 patients colonized or infected with CPE were reported over a 24 months period (January 2012–December 2013). Travel history data were present for 566 patients (missing data: 36%). Only 12% (66 cases out of 566) of the reported CPE carriers were related to a travel abroad with or without hospitalization. Limiting screening practices to only this risk group will thus no longer be sufficient to avoid the spread of CPE in Belgium.

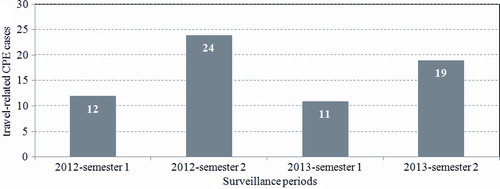

Among 86 participating laboratories, 24 (28%) reported one or more than one confirmed cases of travel-related CPE. The total number of travel-related CPE cases was higher during the last semester of each surveillance year (doubled in comparison to the first semester), undoubtedly influenced by summer tourism ().

Figure 1. Semestrial number of travel-related carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae (CPE) cases in Belgium (n = 66): surveillance data 2012–2013.

The majority of the imported CPE cases (62%, 41/66 cases) were reported by six of the seven Belgian university hospitals, while general hospitals reported only 36% (24/66) of the travel-related cases highlighting the fact that patients repatriated from foreign countries are predominantly admitted in large tertiary care hospitals. Half of all imported CPE cases were reported by hospitals from the Brussels area: 33 cases on total; among them 26 cases by three university hospitals from the Brussels area.

The visited country was known for 65 patients with travel-related CPE: 29 cases (45%) were related to a stay in the African continent, and 18 (28%) had travelled in Asia and 18 (28%) in a European country.

The majority of the cases reported from Africa originated from North African countries, especially those from the Maghreb and from the middle East: Morocco (n = 15), Tunisia (n = 5), Egypt (n = 4), Algeria (n = 2), Senegal (n = 2), and Libya (n = 1), and they mostly consisted of OXA-48-like producing organisms (25 of the 29 African CPE cases). OXA-48-like producing CPE were also very frequently involved in cases acquired in Turkey (n = 10). On the other hand, NDM-producing CPE were mostly imported from the Indian subcontinent and from South Eastern Asia (India, Pakistan, and Vietnam, n = 6). Carbapenemases from CPE cases related to a recent stay or hospitalization in a European country were mostly of KPC type (Greece and Italy, n = 10) or OXA-48 (Greece, n = 4). The most frequently concerned European countries were Greece (n = 11) and Italy (n = 4).

Discussion

CPE carriage among travellers, an underestimated at risk group

Although the proportion of patients colonized or infected with CPE after a stay abroad accounts for only 12% of all reported CPE cases in Belgium in 2012–2013, it is important to remain alert with respect to this, particularly at risk group whose importance is undoubtedly largely underestimated (information on travel (and hospitalization) abroad was missing in more than one-third of the CPE cases declared in Belgium). This lack of exhaustiveness is probably due to the design of the surveillance, mostly initiated from the microbiological laboratory and rarely by field workers (hospital hygiene teams, and medical and paramedical teams working in the hospitalization wards). History data, including details about travel and contacts with healthcare in a foreign country, are crucial but appear extremely difficult to obtain in daily practice. Ideally, this information should be directly obtained from patients or from their close relatives.

Considering the globalization of CPE, the use of a list of endemic/epidemic countries is no longer useful

The Superior Health Council recommends to detect carriage of CPE in patients transferred from hospitals abroad in endemic or epidemic situation for CPE (advice 7 December 2011) [Avis du Conseil Supérieur de la Santé nr. 8791 (7 décembre 2011): Mesures à prendre suite à l'émergence des entérobactéries productrices de carbapénémases (CPE) en Belgique]. Whereas the relevance of mapping endemic countries for CPE may have appeared justified in 2011, this approach is now largely superseded and inefficient in a context of rapid globalisation. Actually, one should consider every patient transferred from foreign hospitals as at risk for CPE carriage (or infection). The aforementioned studies clearly showed that travelling (healthy) in certain endemic regions such as the Indian subcontinent even without any previous healthcare contact could also be a risk factor for acquisition of ESBL and/or CPE, hence further expanding the risk groups to be screened upon hospital admission in Belgium.

The potential sources of import of travel-related CPE are diverse

Growing mobility of human populations and increase of world tourism

The exploding mobility of populations largely contributes to the spread of MDROs worldwide.Citation17 Owing to its central position in Europe, Belgium is an important cross point for both tourism and professional activities (in particular due to the presence of European and international institutions). In addition, Belgian citizens do also frequently travel. It was estimated that in 2012, [Service Public Fédéral Economie: Enquête voyages, données 2012] Belgian residents had made 7.8 million travels abroad (>4 nights), including 6.5 million trips in European countries and 1.3 million trips outside Europe.

Migration flows in Belgium

The significant migratory flows undoubtedly also play a role in the globalisation of antimicrobial resistance and in the dissemination of MDROs between continents and between countries.Citation18 In 2012, 10.6% of the Belgian population was of foreign citizenship (versus 8.4% in 2001) [Service Public Fédéral Economie, Direction Générale du Statistique et information économique: Aperçu statistique de la Belgique: chiffres clés 2013]. The principal countries of origin of foreign residents in Belgium were Italy (13.7%), France (12.8%), the Netherlands (12.1%), and Morocco (7.4%). These four countries together accounted for half of the Belgian population of foreign nationality. During the last decade, the largest surge of immigration in Belgium came from Poland (sevenfold increase; 4.8% in 2012) and from Romania (tenfold increase; 3.6% in 2012). Poland for instance, alike Italy and Greece, had to deal with large interregional CPE outbreaks, mainly of the KPC type, that were most probably imported from the United States.Citation19 A steadily growing number of asylums and refugees has been observed over the recent years in Belgium, and this population subgroup should also be included as at risk for carriage of MDRO in general and CPE in particular when seeking hospital care, especially in the early period (within the first year) after arrival.

Resident aliens often maintain regular contacts with their family in their country of origin, and could contribute to cross-border dissemination of CPE and other MDROs. Belgium has the highest concentrations of citizens with foreign nationality in some municipalities from and in the periphery of Brussels, in other large urban areas (Antwerp, Liege, Charleroi), in border regions, in university towns, and around the historical industrial axis of Wallonia.

Medical repatriations from foreign hospitals

In Belgium, emergency repatriations of patients with complex medical conditions or traumatisms from foreign countries are ensured by various international/national organizations (such as health insurances, travel insurances). This explains the difficulty to quantify the total number of repatriated patients and their characteristics in Belgium. MUTAS [projet intermutualiste pour soins médicaux d'urgence en Belgique], one of these organizations, reported in 2013 a total of 649 cases of medical repatriation from abroad (81% from a country in Europe, 12% from Africa, and 7% from Asia) to a Belgian hospital.

Screening for carriage of MDRO (including CPE) among patients directly repatriated from a hospital abroad to a Belgian hospital could be relatively easy to implement in theory, if standard procedures were systematically initiated by the international organizations in charge of these medical transfers.

On the other hand, it seems much more difficult to target patients having travelled abroad and returning back home prior to a subsequent admission in a hospital in Belgium. Obviously, the identification of travellers who made a journey in countries endemic for CPE (e.g. India) without any exposure to healthcare services can be even more challenging.

The collection of patient history data concerning a stay or healthcare contact (in the previous year) in a foreign country appears essential but remains, however, very difficult to obtain in daily practice. Yet, such a strategy has been successfully applied in the Netherlands for several decades for the control of transmission of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). This should encourage us to integrate the systematic screening for information on international travel in the medical practices and questionnaires upon admission to hospital. First-line healthcare workers (HCW), in particular general practitioners and homecare teams, should also be informed about the importance of (travel-related) MDROs, including CPE, because this antimicrobial resistance mechanism is currently insufficiently known and often mistakenly assumed as a problem limited to acute hospitals only.

Scheduled medical care for foreign patients in Belgium

The quality and access to healthcare services in Belgium are considered excellent. For several years now, a growing number of foreign patients seek care in Belgian healthcare structures due to the lack of resources and limited access to healthcare resulting in long waiting lists in their country of origin [Observatoire de la mobilité des patients: Rapport annuel 2012 (INAMI et SPF Santé Publique) and (Soins Programmés à des patients étrangers: Impact sur le système Belge de Soins de Santé: KCE reports 169B)]. Between 2004 and 2008 [Données Résumé Clinique Minimum: 2004–2008], the number of foreign patients residing outside Belgium and being hospitalized in a Belgian hospital increased by 60%. In 2010, 1.5% of the hospitalizations in Belgian hospitals concerned foreign patients residing outside Belgium. In 2010 also, 29 Belgian hospitals had on total 83 contracts with foreign countries for scheduled medical care (such as cancer therapy; cardiovascular, plastic, or orthopaedic surgery; or reproductive medicine). The major part of the foreign patients using scheduled medical care in Belgium originate from the Netherlands (58.4%), France (19.8%), the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg (4.5%), and to a lesser extent from Italy and Great Britain (less than 3% each).

These patients can cycle ESBLE and/or CPE or other MDROs (vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus, MRSA, Acinetobacter baumannii, etc.) between Belgian hospitals and their country of origin, which contributes to the cross-border transmission and spread of these MDROs.

Residents living in nursing homes located in the border areas

Residents from nursing homes for elderly constitute another potential source of dissemination of MDROs, in particular in the country border areas. In 2004, one nursing home located at the French–Belgian border was at the source of importation of ESBL-producing (type VEB-1) A. baumannii isolates from France (in a large interregional outbreak at that time) to several Belgian acute hospitals [Enquête épidémiologique relative à A. baumannii producteur de BLSE (type VEB-1) en Belgique. IPH/EPI-reports: Nr. 2004 – 18. (http://www.nsih.be/download/acinetobacter/acinetobacter.pdf)]. A significant proportion ( ± 60%) of the nursing home residents located at the French–Belgian border were French citizens and received hospital care whenever needed either in France or in Belgium, hence facilitating the spread of MDROs between countries. Nursing home residents colonized with CPE (and also with ESBLE) are generally asymptomatic faecal carriers and may remain colonized for prolonged periods (from one to several months).

Daily life contacts (close care, revalidation care, etc.) are opportunities for transmission of MDROs from residents towards medical/nursing staff or to the environment (and vice versa). While the clinical impact of MDRO carriage (including CPE) is probably rather limited for healthy residents, the longstanding carriage of resistant microorganisms may fuel and increase the reservoirs as it has been shown earlier for e.g. MRSA, and they can act as vectors for their dissemination in the community as well as in hospitals.

Healthcare workers having travelled abroad can act as a potential contamination source for patients

Although data on HCWs acting as a source or as a reservoir for contamination of patients hospitalized or institutionalized in long term care facilities (LTCFs) are scarce, cases of CPE transmission from HCWs having travelled abroad to patients have been reported occasionally.Citation20 The free movement of persons, goods, services, and capital within the European Union contributes to the increasing number of foreign HCWs in Belgian healthcare settings. This population group maintains close family contacts by frequent travels to their home country.

Actually, the screening of medical and paramedical staff for CPE carriage (or for the carriage of any MDROs) is not advised for sporadic or grouped cases, but this measure can be useful in specific settings when an epidemic cannot be controlled in spite of the strict application of preventive measures for the control of transmission.

Belgium, a country with a high population density

In addition to the various potential hazards of CPE importation developed above, Belgium may be considered at risk for dissemination of CPE and other MDROs because of the high density of its population and the numerous healthcare structures and networks that exist in our country. Indeed, the population density in Belgium (367 inhabitants/km2) is amongst the highest in Europe [Eurostat, population density, data 2012]. Only Malta (1327/km2) and the Netherlands (497/km2) have a higher population density. The population density in Belgium varies strongly by provinces and regions and is twice higher in the Flanders region compared to the Walloon region. The highest population density is observed in the area of Brussels-Capital (7249 inhabitants/km2), followed by the provinces of Antwerp (643), Flemish Brabant (523), and East Flanders (496). In the provinces of Luxembourg (62), Namur (133), and Liege (284), the population density is the lowest.

Several publications suggest a link between population density (and overcrowding) and the prevalence of antimicrobial resistance,Citation21,Citation22 increasing the number of resistant bacteria circulating in the community and increasing the risk for cross-transmission between humans living in proximity.

Urban areas, especially from the largest towns in Belgium, may cumulate several potential risk factors for import and dissemination of CPE: a high population density coupled with a dense healthcare network, concentration of university hospitals, larger proportion of immigrants, asylum seekers and refugees, and higher number of tourist travellers.

In 2012–2013, one-third of the CPE cases declared in Belgium presumably had no previous contacts with a Belgian healthcare structure (acute hospital, LTCFs) in the 12 months preceding CPE detection. Even though the notion of previous contacts with care institutions is probably underestimated (for the same reasons as mentioned for travel/hospitalisation abroad), it suggests that a hidden transmission of CPE may already be ongoing in the community in Belgium. Studies are needed in order to assess the extent of these reservoirs in the different healthcare sectors and in the various population groups in the community.

While actually there is not enough evidence to support screening and isolating every person who has recently travelled, it seems at least suitable to consider each patient who received medical care in a foreign country as a person at risk for CPE carriage (as well as for other MDROs), whatever be the country visited and even if the level of risk can probably be very different according to the visited geographical area.

The active surveillance program initiated in 2012 aimed to estimate the proportion of travel-related CPE cases in Belgium. This paper highlights the limits of this surveillance (missing information in more than one-third of the cases) and it reviews other possible sources of import of CPE, with or without contact with healthcare systems/structures abroad. The previously enumerated facts raise several questions and have implications for policies regarding infection control measures. The impact of international travel on the spread of MDROs is crucial to understand both on the patient and on the public health levels in order to determine optimal interventions and policies.

Acknowledgements

We thank the National Reference Center for Monitoring of Antimicrobial Resistance in Gram-Negative Bacteria for the precious collaboration, and all the microbiologist colleagues and infection control teams for their very active participation in this surveillance program. We are grateful to the Federal Public Service Economy and to the MUTAS-travel insurance for sharing travel-related data of Belgium.

Disclaimer Statements

Contributors All authors contributed by revising or by writing the article. Data collection, analysis and interpretation was performed by BJ and YG.

Funding The National Reference Centre for Monitoring Antimicrobial Resistance in Gram-Negative Bacteria is financially supported by the Belgian Ministry of Social Affairs through a fund within the health insurance system. Te-Din Daniel Huang was supported in part by a research grant from the Fondation Mont-Godinne. The surveillance unit (WIV-ISP) is financed through the hospital budget of participating hospitals (Royal Decree, 19 June 2007).

Conflicts of interest The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethics Approval None required.

References

- Walsh TR, Weeks J, Livermore DM, Toleman MA. Dissemination of NDM-1 positive bacteria in the New Delhi environment and its implications for human health: an environmental point prevalence study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2011;11(5):355–62.

- Cuzon G, Naas T, Bogaerts P, Glupczynski Y, Huang TD, Nordmann P. Plasmid-encoded carbapenem-hydrolyzing beta-lactamase OXA-48 in an imipenem-susceptible Klebsiella pneumoniae strain from Belgium. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52(9):3463–4.

- Glupczynski Y, Rodriguez-Villalobos H, Bogaerts P, Blairon L, Gérard M, Aoun M, et al. Emergence of panresistant VIM-1 producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in Belgian hospitals. 19th European Congress of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ECCMID); 2009 May 16–19; Helsinki, Finland, 2009.

- Bogaerts P, Montesinos I, Rodriguez-Villalobos H, Blairon L, Deplano A, Glupczynski Y. Emergence of clonally related Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates of sequence type 258 producing KPC-2 carbapenemase in Belgium. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2010;65(2):361–2.

- Bogaerts P, Bouchahrouf W, deCastro RR, Deplano A, Berhin C, Pierard D. Emergence of NDM-1-producing Enterobacteriaceae in Belgium. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55(6):3036–8.

- Huang TD, Bogaerts P, Berhin C, Jans B, Deplano A, Denis O. Rapid emergence of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteria_ceae isolates in Belgium. Euro Surveill. 2011;16(26):19900.

- Ruppe E, Armand-Lefevre L, Estellat C, El-Mniai A, Boussadia Y, Consigny PH, et al. Acquisition of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae by healthy travellers to India, France, February 2012 to March 2013. Euro Surveil. 2014;19(14):20768.

- Murray BE, Mathewson JJ, DuPont HL, Ericsson CD, Reves RR. Emergence of resistant fecal Escherichia coli in travelers not taking prophylactic antimicrobial agents. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1990;34(4):515–8.

- Laupland KB, Church DL, Vidakovich J, Mucenski M, Pitout JD. Community-onset extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) producing Escherichia coli: importance of international travel. J Infect. 2008;57(6):441–8.

- Tangden T, Cars O, Melhus A, Lowdin E. Foreign travel is a major risk factor for colonization with Escherichia coli producing CTX-M-type extended-spectrum beta-lactamases: a prospective study with Swedish volunteers. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54(9):3564–8.

- Ostholm-Balkhed A, Tarnberg M, Nilsson M, Nilsson LE, Hanberger H, Hallgren A. Travel-associated faecal colonization with ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae: incidence and risk factors. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2013;68(9):2144–53.

- Paltansing S, Vlot JA, Kraakman ME, Mesman R, Bruijning ML, Bernards AT, et al. Extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae among travelers from the Netherlands. Emerg Infect Dis. 2013;19(8):1206–13.

- Tham J, Odenholt I, Walder M, Brolund A, Ahl J, Melander E. Extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli in patients with travellers' diarrhoea. Scand J Infect Dis. 2010;42(4):275–80.

- Arcilla MS, vanHattem JM, Bootsma MC, vanGenderen PJ, Goorhuis A, Schultsz C. The carriage of multiresistant bacteria after travel (COMBAT) prospective cohort study: methodology and design. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:410.

- Freeman JT, McBride SJ, Heffernan H, Bathgate T, Pope C, Ellis-Pegler RB. Community-onset genitourinary tract infection due to CTX-M-15-Producing Escherichia coli among travelers to the Indian subcontinent in New Zealand. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47(5):689–92.

- Ahmed-Bentley J, Chandran AU, Joffe AM, French D, Peirano G, Pitout JD. Gram-negative bacteria that produce carbapenemases causing death attributed to recent foreign hospitalization. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57(7):3085–91.

- van der Bij AK, Pitout JD. The role of international travel in the worldwide spread of multiresistant Enterobacteriaceae. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012;67(9):2090–100.

- MacPherson DW, Gushulak BD, Baine WB, Bala S, Gubbins PO, Holtom P. Population mobility, globalization, and antimicrobial drug resistance. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15(11):1727–32.

- Baraniak A, Grabowska A, Izdebski R, Fiett J, Herda M, Bojarska K. Molecular characteristics of KPC-producing Enterobacteriaceae at the early stage of their dissemination in Poland. 2008-2009. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55(12):5493–9.

- Perez F, Van Duin D. Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae: a menace to our most vulnerable patients. Cleve Clin J Med. 2013;80(4):225–33.

- Bruinsma N, Hutchinson JM, van den Bogaard AE, Giamarellou H, Degener J, Stobberingh EE. Influence of population density on antibiotic resistance. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2003;51(2):385–90.

- MacDougall C, Powell JP, Johnson CK, Edmond MB, Polk RE. Hospital and community fluoroquinolone use and resistance in Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli in 17 US hospitals. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41(4):435–40.