Abstract

Objective:

Clinical benefits of achieving a sustained virologic response (SVR) with hepatitis c virus (HCV) therapy beyond reducing liver-related outcomes have not been documented in HIV-coinfected patients, who have multiple competing health problems. To gauge the potential benefits of curing HCV in coinfected people, we examined changes in health-related quality of life (HRQOL), healthcare and substance use, and overall mortality after treatment for HCV Coinfection.

Design:

Prospective multicentre cohort study.

Methods:

Among patients treated for HCV in the Canadian Coinfection Cohort study, self-reported HRQOL (using the EQ-5D), inpatient and outpatient medical visits, and substance use were assessed before, 6 months and 1 year after completing HCV therapy, comparing SVR-achievers and non-responders. Analysis of covariance and zero-inflated negative binomial regression were used to model the effects of SVR on HRQOL and healthcare use, respectively.

Results:

Of 1145 patients chronically infected with HCV, 223 (19%) received treatment while under follow-up in the cohort and had HRQOL data collected – 86 (36%) achieved SVR, 68 (29%) did not, 30 (13%) had ongoing treatment, and 39 (17%) had unknown responses. Compared to non-responders, those achieving a SVR had higher HRQOL scores over time (11-unit increase 1 year posttreatment, 95% CI: 2, 21 measured 1 year posttreatment) and a lower rate of health service utilization (adjusted incidence rate ratio: 0.5, 95% CI: 0.3, 0.9). Short-term mortality was low but appeared lower in SVR-achievers (incidence rates: 0.10 vs 0.12 deaths per 100 person-years). However, after successful treatment, a substantial number of patients increased alcohol consumption and continued to inject drugs.

Conclusions:

Successful HCV treatment results in a range of health benefits for HIV/HCV-coinfected patients. Ongoing substance use, however, may mitigate the short- and long-term benefits associated with curing HCV.

Introduction

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) coinfection is common due to shared routes of transmission principally through injection drug use.Citation1,Citation2 In the era of effective HIV treatment, patients coinfected with HIV and HCV live long enough to develop late HCV-related sequelae including liver failure, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma.Citation3 In coinfected patients, liver disease has surpassed AIDS as a leading cause of hospitalization and death.Citation4 Unlike HIV, a therapeutic cure for HCV–sustained virologic response (SVR), traditionally defined as a negative HCV RNA 6 months after completion of therapy (now SVR24)- is possible using interferon-based regimens with or without direct-acting antiviral drugs for HCV.Citation3 The recent development of safe, tolerable, and effective interferon-sparing therapy offers the promise of cure for all infected patients.Citation5,Citation6 In HCV monoinfection, SVR rates have increased from between 65 and 80% in genotypes 2 and 3 and < 40% in genotype 1 (for treatment with pegylated-interferon and ribavirin)Citation7 to over 90% independent of genotype and stage of disease using modern HCV therapy. In HIV coinfection, absolute SVR rates are historically 20–30% lower on average than for monoinfected patients,Citation8,Citation9 but this gap is likely to close with direct-acting antiviral regimens.Citation10,Citation11

Successful treatment of HCV monoinfection yields a range of measurable health benefits including improved liver histology, better health-related quality of life (HRQOL), reduced liver-related morbidity, and increased survival.Citation12–Citation14 Patients with HIV/HCV-coinfection have multiple competing health concerns. The benefits of SVR beyond reduced liver-related complications and survival have been rarely exploredCitation15,Citation16 despite the growing burden of coinfection.Citation17 Healthcare expenditures related to HCV infection are rising dramaticallyCitation18 as are the cost of new HCV treatments.Citation19 The high cost of these therapies may be justified if successful treatment leads to important benefits for individuals, for population health and for the healthcare system overall, and provided that continued harm from substance use does not reduce gains associated with curing HCV.Citation20 In order to gauge the potential benefits of curing HCV in the setting of HIV coinfection, we examined changes in HRQOL, health service use, mortality, and substance use among patients initiating treatment for HCV in the Canadian Coinfection Cohort (CCC), comparing patients who achieved a SVR with those who did not.

Methods

Setting and participants

The CCC is a prospective cohort enrolling adult patients with HIV infection, who are HCV seropositive from 18 HIV centers across six Canadian provinces since 2003.Citation21 The cohort recruits participants from various care settings (i.e. university-based and community clinics, outreach programs, mobile care units serving drug users in the street) and risk profiles (i.e. injection drug users, men who have sex with men, Aboriginal people, women), and has sought to include marginalized individuals. As of July 1, 2014, 1318 participants had been recruited. The study was approved by the ethics boards of all participating sites and the Community Advisory Board of the CIHR Canadian HIV Trials Network.

Participants attended follow-up visits scheduled every 6 months. Sociodemographics, substance use behaviors, and healthcare use were self-reported. At each visit, treatment information was collected by research coordinators and laboratory tests were carried out. Health-related quality of life was measured using the EQ-5D™ questionnaire in English or French.Citation22 Participants scored current health on a visual analog scale (VAS) from 0 to 100 (worst to best imaginable health) and reported levels of difficulty experienced (no/some/extreme problems) in five health domains: mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain or discomfort, anxiety, or depression). Documentation of deaths was collected by sites and through linkage to provincial vital statistics among patients reported to have died and those lost to follow-up.Citation23

The analytic sample comprised all participants with chronic HCV infection (HCV RNA positive), who initiated HCV treatment during follow-up with available posttreatment HCV RNA data to ascertain SVR status (see below). The presence of HCV RNA was tested using polymerase chain reaction at local laboratories of the participating centers. Participants with previous SVR or spontaneous clearance prior to cohort entry and participants already on HCV treatment at cohort entry were excluded. EQ-5D and health services questions were introduced in the cohort questionnaire as of 2007; hence, those who started HCV treatment before 2007 were also excluded.

Treatment responses

Participants who started antiviral therapy were classified as having the following treatment responses: (i) SVR, (ii) non-responder, (iii) still on treatment at the last recorded visit, or (iv) unknown (no HCV RNA results available after treatment). Any participant with a detectable HCV RNA after 12 weeks of initiating therapy was considered a virologic non-responder.Citation24 Patients without response by 12 weeks are unlikely to achieve SVR, and thus further treatment is not indicated.Citation3,Citation25 Patients with undetectable HCV RNA 6 months or more after treatment discontinuation were considered SVR-achievers (equivalent to SVR24).

Outcomes

Sustained virologic response-achievers were compared to non-responders with respect to the following outcomes: (i) HRQOL, as measured by VAS scores; (ii) rates of health service use; (iii) mortality rates; and (iv) proportion using tobacco, illicit drugs, and alcohol. Since alcohol consumption accelerates liver fibrosis,Citation26 we further examined aspartate aminotransferase to platelet ratio index (APRI) scores, a noninvasive surrogate for fibrosis, which have been validated in HIV/HCV-coinfection.Citation27 Aspartate aminotransferase to platelet ratio index scores were calculated as 100 × (aspartate aminotransferase [IU/l]÷upper limit of normal [IU/l])÷platelet count [109/l].Citation28 A score < 0.5 represents no fibrosis and APRI ≥ 1.5 represents significant fibrosis (corresponding to biopsy score ≥ F2).Citation27,Citation29

Statistical analysis

We examined outcomes immediately prior to treatment at 6 months, and at 1 year posttreatment. We used any study visit within 3 months of the nominal date to represent each of these time points (and the closest visit if more than one). We used Stata 11 (StataCorp. 2009, College Station, TX, USA) for all analyses.

Health-related quality of life

We modeled the association of SVR with VAS scores using analysis of covariance. Sustained virologic response-achievers and non-responders may differ with respect to characteristics that could influence both their likelihood of receiving or responding to treatment and their perceived HRQOL (i.e. gender, socioeconomic status, liver disease stage, co-morbidity, drug use, etc.). Many correlated baseline characteristics, such as education level, income, housing status, drug, and alcohol use, could influence whether an SVR was obtained, as well as the likelihood that HRQOL would improve posttreatment. These characteristics arguably may be encapsulated in a single measure of HRQOL at baseline. Given the small sample size, it was not feasible to adjust for all potential confounders. For efficiency, we therefore adjusted for pretreatment VAS scores as a proxy for both known and unknown confounders. EQ-5D responses were also converted into composite scores known as utilities using a Canadian-based algorithm.Citation30 Utility scores range from 0, reflecting health states valued as equivalent to death, to 1, reflecting perfect health.

Health service use

We compared rates of self-reported health services used since the preceding visit. We modeled the effect of SVR on inpatient visits (overnight hospital stays, emergency room visits), outpatient visits (general practitioner, HIV clinic, specialist), and walk-in clinic visits, adjusting for pretreatment rate of healthcare use. Zero-inflated negative binomial regression was used to account for right-skewness and over-dispersion in count data. An offset term, log(exposure time), accounted for the time elapsed for each patient between pretreatment and outcome measurements.

Mortality

We examined the absolute number of deaths since beginning HCV treatment and the crude overall mortality rates by dividing the number of deaths by the number of person-years at risk since beginning HCV treatment.

Substance use

We described the proportion of participants reporting substance use at each time point. Using linear regression, we modeled the association of SVR with APRI scores, adjusting for pretreatment scores and alcohol use. We transformed the scores using the natural logarithm to approximately normalize these data.

Sensitivity analysis

In a first sensitivity analysis, we used a more liberal definition of SVR than was traditionalCitation12 to maximize the number of participants in our analysis: patients having a negative HCV RNA at any time 12 weeks or more after completing treatment were considered to have achieved an SVR (SVR12). In a second sensitivity analysis, so as not to omit participants who missed specific assessment visits at 6 months and 1 year, we considered HRQOL: (i) at the first visit after treatment completion regardless of when it occurred, and (ii) at the first visit at least 12 weeks after treatment completion (i.e. where HCV RNA results were available). In both sensitivity analyses, we estimated the effect of SVR12 on HRQOL, adjusting for pretreatment scores and for the time elapsed between the end of treatment and the visit date.

Results

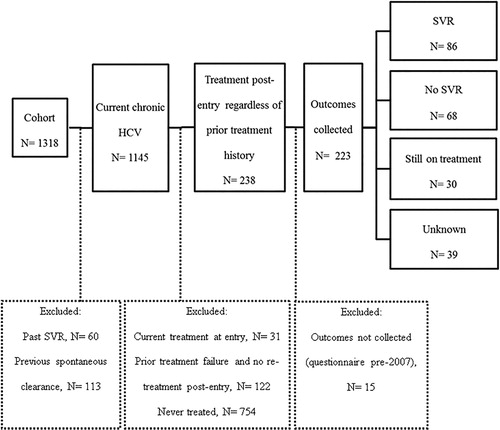

The sample included 1145 eligible participants, 238 of whom started HCV treatment () – for a cumulative incidence of treatment initiation of 21%. Of the patients who started HCV treatment, 223 had available outcomes data collected and thus were included in analysis. Treatment rates were lower among women (16%) and Aboriginal people (7%). The majority of patients had used injection drugs (80%) and 28% were men who had sex with men ().

Figure 1. Study flow of participant selection. HCV: hepatitis C virus; SVR: sustained virologic response.

Table 1. Characteristics of Canadian Coinfection Cohort (CCC) participants overall (at cohort enrollment) and of participants beginning HCV treatment (at their pretreatment visit)

Sustained virologic response

Of 223 participants included, 86 (38%) achieved SVR, 68 (30%) did not respond, 30 (13%) had ongoing treatment, and 39 (17%) had unknown treatment responses. Sustained virologic response was higher in HCV genotype 2 or 3 (76%) compared with genotype 1 (50%). Aside from higher median income among responders, there were no appreciable differences between responders and non-responders with respect to baseline characteristics. All participants received interferon-based therapy; combined with direct-acting antivirals in 41 cases. The median time from cohort entry to treatment initiation was 15 months (IQR: 6, 34).

Health-related quality of life

Sustained virologic response-achievers and non-responders had similar pretreatment VAS scores – 75 (Interquartile range [IQR]: 60, 80) and 70 (IQR: 50, 83), respectively. After adjustment, SVR was significantly associated with improved VAS scores at 1 year (11.4 units; 95% CI:2, 21), but not at 6 months (5.3 units; 95% CI: − 3, 14). The health utility scores also improved among patients with SVR compared to those without: 0.88 versus 0.78 at 1 year posttreatment. At 1 year after completion of therapy, SVR-achievers reported greater reductions in difficulties with self-care (7% pre- and 6% posttreatment compared with 4% pre- and 5% posttreatment in non-responders) and usual activities (from 34% pre- to 25% posttreatment vs 43% pre- and 42% posttreatment), and reported less anxiety/depression at 1 year (53 vs 57%), but more pain (63 vs 43%) than non-responders.

Health service use

After adjustment, successful HCV treatment was associated with fewer healthcare visits. Sustained virologic response-achievers used inpatient services 60% less frequently than non-responders and also had 40% fewer outpatient visits ().

Table 2. Incidence rates of health services used (per 100 person-years) among SVR-achievers compared with non-responders

Mortality

During follow-up, there were two deaths among SVR-achievers and five deaths among non-responders. Two of the reported deaths (both among non-responders) were liver or overdose related. Mortality rates were slightly lower among SVR-achievers than non-responders (0.10 vs 0.12 deaths per 100 person-years). No adjusted analyses were performed, given the low mortality.

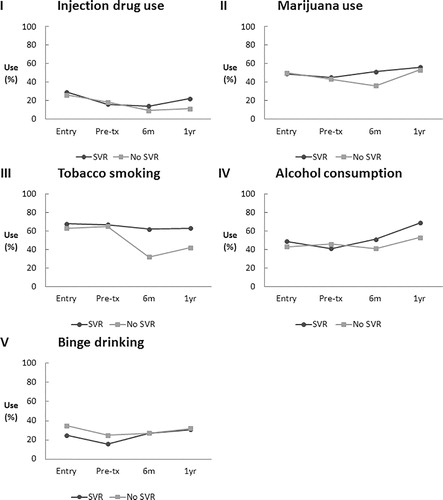

Substance use

Qualitatively, patients reported less injection drug use, tobacco use, and alcohol consumption at the time of treatment initiation compared with cohort entry (). However, alcohol consumption increased posttreatment for both SVR and non-responder groups (from 49 to 69% and 43 to 63%, respectively). Binge alcohol drinking (having ≥ 6 drinks on one occasion) also increased in both SVR and non-responder groups. Despite increased alcohol use, APRI scores fell below levels found at cohort entry after successful HCV treatment (). Posttreatment median scores were consistent with the absence of fibrosis (median 0.4, IQR: 0.3, 0.9). In the absence of SVR, APRI increased to a median of 0.8 (IQR: 0.6, 1.8). After adjusting for pretreatment APRI scores, SVR was significantly associated with improved APRI scores 6 months and 1 year posttreatment ( − 0.74 [95% CI: − 1.1, − 0.3] and − 0.6 [95% CI: − 1.1, − 0.1], respectively). Sustained virologic response remained significantly associated with APRI improvement after further adjusting for alcohol use 6 months ( − 0.4 [95% CI: − 0.7, − 0.2]) and 1 year posttreatment ( − 0.6 [95% CI: − 1.1, − 0.2]).

Figure 2. Proportion of patients reporting substance use over time (cohort entry, before treatment, 6 months after treatment, 1 year after treatment) comparing SVR-achievers and non-responders. SVR: sustained virologic response; pre-tx: pretreatment.

Figure 3. Liver fibrosis over time (cohort entry, before treatment, 6 months after treatment, 1 year after treatment) comparing SVR-achievers and non-responders. Aspartate aminotransferase to platelet ratio index (APRI) scores < 0.5 indicate no fibrosis. Aspartate aminotransferase to platelet ratio index scores ≥ 1.5 indicate significant fibrosis. Sustained virologic response was significantly associated with improved APRI scores 6 months and 1 year posttreatment after adjusting for pretreatment APRI scores: linear regression coefficient − 0.7 (95% CI: − 1.1, − 0.3) and ( − 0.6 [95% CI: − 1.1, − 0.1]), respectively. APRI: aspartate aminotransferase to platelet ratio index; SVR: sustained virologic response; Q1: first quartile; Q3: third quartile.

![Figure 3. Liver fibrosis over time (cohort entry, before treatment, 6 months after treatment, 1 year after treatment) comparing SVR-achievers and non-responders. Aspartate aminotransferase to platelet ratio index (APRI) scores < 0.5 indicate no fibrosis. Aspartate aminotransferase to platelet ratio index scores ≥ 1.5 indicate significant fibrosis. Sustained virologic response was significantly associated with improved APRI scores 6 months and 1 year posttreatment after adjusting for pretreatment APRI scores: linear regression coefficient − 0.7 (95% CI: − 1.1, − 0.3) and ( − 0.6 [95% CI: − 1.1, − 0.1]), respectively. APRI: aspartate aminotransferase to platelet ratio index; SVR: sustained virologic response; Q1: first quartile; Q3: third quartile.](/cms/asset/6c632d08-6d0c-4083-a09f-575aaa5c875a/yhct_a_11732837_f0003_b.jpg)

Sensitivity analyses

Using the alternative definition of SVR12, 11 patients of unknown SVR status were reclassified as SVR-achievers. Reclassification of these patients did not affect the results (data not shown). When we examined other time points in the second sensitivity analysis, results also did not change.

Discussion

In HIV/HCV-coinfected patients, SVR is associated with a range of improvements in health that could result in substantial improvement in quality of life and in healthcare cost-savings. Sustained virologic response-achievers reported better HRQOL, reduced use of health services, had improved APRI scores, and appeared to have lower mortality than non-responders over the short-term, although there were few deaths in both groups. However, successful HCV therapy was associated with ongoing and increased substance use which may limit these health benefits over the longer term.

Although there has been limited use of the EQ-5D in HIV, this instrument has shown responsiveness to antiretroviral therapy, adverse events, and opportunistic infections, mostly in advanced HIV and in developing countriesCitation31 and in trials of HIV therapy.Citation32 To date, there have been no studies using the EQ-5D to assess HCV treatment, despite having been found valid and responsive in hepatitis C monoinfection.Citation33 Our VAS scores are similar to those reported among HIV-monoinfected patients in Africa (60 before and 70–76 after antiretroviral treatment vs 80 in healthy controls)Citation3–Citation5 and among Vietnamese injection drug users with HIV.Citation34 This similarity in HRQOL, despite HIV treatment and care being readily available in Canada, suggests poor social circumstances and addictions erode HRQOL. The magnitude of change in HRQOL observed (11 in VAS scores 1 year posttreatment) is comparable to improvements seen after successful chemotherapy for 11 types of cancer, where patients consider absolute changes of 8–11 to be clinically important – that is, patients perceive benefits.Citation35 Smaller changes in VAS score (+3 points) have been considered clinically important among injection drug users with HIV on methadone maintenance therapy.Citation34 Thus, the degree of change we observed with HCV therapy can be considered clinically important, particularly if sustained over the longer term. Health-state utilities represent an individual's preferred value for specific health states relative to full health. Baseline utilities reported by our patients are very consistent with Canadian data for patients living with HCV (between 0.73 and 0.79), whereas utilities clearly increased post SVR to 0.88 becoming consistent with good or near-perfect health.Citation36

The costs of untreated HCV infection are enormous.Citation37 HCV is the leading cause of cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma, and liver transplantation.Citation17 Costs of treating the chronic sequelae of HCV among injection drug users in Canada are estimated to rise to $210 million annually by 2026.Citation38 Coinfected patients have shown “alarming” annual increases of 30–40% in liver-related and all-cause hospitalizations.Citation17 In British Columbia, the mean acute inpatient cost per 100 patient-days ranges from $446–$8667 depending on the stage of liver disease.Citation39 Therefore, a reduction in healthcare use overall, and in inpatient admissions in particular, among SVR-achievers implies substantial cost-savings downstream despite high front-end costs of treatment. Sustained virologic response also appeared to be associated with a reduction in outpatient visits, which may reflect improved wellbeing of patients and/or a reduction in frequency of medical follow-up required by specialists. Although deaths were infrequent, improved all-cause mortality rates among SVR-achievers compared to non-responders may exist over the short term, consistent with the 5-year follow-up data among Spanish coinfected patients (0.26 vs 1.82 per 100 person-years, respectively).Citation16

Ongoing risk behaviors common in the coinfected population could limit the benefits of SVR through increased risk of reinfection and liver injury from continued substance use. Medical professionals advise against substance use, particularly alcohol, to both reduce risk of cirrhosis and to improve HCV treatment responses.Citation8,Citation9,Citation12 It appears that the majority of patients achieving SVR were able to reduce substance use prior to initiating treatment and remain abstinent thereafter. However, many reverted to drinking above pretreatment levels following completion of therapy. While regression to the mean can, in part, explain the phenomenon, the reversion is consistent with the chronic, relapsing nature of substance use disorders regardless of SVR status. The 22% who continued injection drug use after successful HCV treatment remain at risk for HCV re-infection.Citation40 Reported rates of reinfection among injection drug users have been as high as 25–31 per 100 person-years.Citation41,Citation42 These findings underscore the need to employ a long-term care approach for underlying substance use disorders, that is integrated with HCV treatment in order to reduce the need for re-treatment using costly interferon-sparing regimens following reinfection.

Our results should be widely generalizable to Canadian coinfected patients in care. The CCC includes approximately 20% of coinfected Canadians who have accessed care.Citation15 Our recruitment from primary and tertiary care clinics in urban and semiurban areas across Canada is broadly representative of the diverse coinfection population in care.Citation21 Our treatment initiation rate (21%) is comparable to rates among persons with HCV monoinfection (18.6% in Toronto community-based centers and 37.8% in a large Montreal hospitalCitation16,Citation17) but higher than that reported in the US overall, where under 15% of HCV infected are estimated to have received HCV therapy.Citation43 However, because relatively few patients get treated, the absolute number of patients initiating HCV treatment in our study was small, limiting our power to detect differences for some outcomes or adjusting for multiple covariates. Only interferon-based therapies were evaluated. Several outcomes were self-reported, which may introduce bias due to poor recall and social undesirability. However, self-reported substance use has been shown to be valid among drug users in care where social desirability bias is minimized by long-standing clinical relationships.Citation44,Citation45 Self-reported health care use has also been validated in AIDS patients despite the potential for poor recall.Citation46 Prior to treatment, SVR-achievers used fewer inpatient services than non-responders, suggesting they were already healthier. Despite adjusting for baseline healthcare use, residual confounding may remain. Reduction in APRI scores may reflect reduced inflammation, increased platelets, or short-term improvements in fibrosis.

Conclusion

A revolution in HCV treatment is clearly underway. Simpler, more tolerable and highly effective regimens are becoming available, offering the real possibility of cure for most persons infected with HCV. As these new therapies become accessible and widely used, our findings suggest curing HCV will lead to important health and economic benefits for the HIV/HCV population and the healthcare system provided attention is paid to managing substance use and addictions.

Acknowledgements

The Canadian Coinfection Cohort (CTN222) investigators are: Drs Jeff Cohen, Windsor Regional Hospital Metropolitan Campus, Windsor, ON; Brian Conway, PENDER Downtown Infectious Diseases Clinic, Vancouver, BC; Curtis Cooper, The Ottawa Hospital – Research Institute, Ottawa ON; Pierre Côté, Clinique du Quartier Latin, Montréal, QC; Joseph Cox, MUHC IDTC – Montréal General Hospital, Montréal, QC; John Gill, Southern Alberta HIV Clinic, Calgary, AB; Shariq Haider, McMaster University Medical Centre – SIS Clinic, Hamilton, ON; Aida Sadr, Native BC Health Center, St-Paul's Hospital, Vancouver, BC; Lynn Johnston, QEII Health Science Center for Clinical Research, Halifax, NS; Mark Hull, BC Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS, Vancouver, BC; Julio Montaner, St. Paul's Hospital, Vancouver, BC; Erica Moodie, McGill University, Montreal, QC; Neora Pick, Oak Tree Clinic, Children's and Women's Health Centre of British Columbia, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC; Anita Rachlis, Sunnybrook & Women's College Health Sciences Centre, Toronto, ON; Danielle Rouleau, Centre Hospitalier de l'Université de Montréal, Montréal, QC; Roger Sandre, Health Sciences North – The HAVEN/Hemophilia Program, Sudbury, ON; Joseph Mark Tyndall, Department of Medicine, Infectious Diseases Division, University of Ottawa, Ottawa ON; Marie-Louise Vachon, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Québec, Québec, QC; Steve Sanche, SHARE University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, SK; Stewart Skinner, Royal University Hospital & Westside Community Clinic, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, SK; and David Wong, University Health Network, Toronto, ON.

We thank Dr Aslam Anis for providing the SAS codes for the EQ-5D Canadian weights. We thank study coordinators and nurses for their assistance with study coordination, participant recruitment, and care. We are grateful to the cohort participants for their enrollment.

Disclaimer Statements

Contributors

Study design: MY, JY, KCR-K, KS, CG, and MBK; data analysis: MY and KCR-K; wrote first draft: MY and MBK; contributed to subsequent drafts: MY, JY, KCR-K, KS, CG, CC, JC, JG, MH, EM, AR, SW, and MBK. This work was presented in part at the 22nd Annual Canadian Conference on HIV/AIDS Research – CAHR 2013 (Vancouver, April 2013), but otherwise has not been published or submitted for publication elsewhere.

Funding

The Canadian HIV/HCV Coinfection Cohort was funded by the Fonds de recherche du Québec – Santé (FRQS), Réseau SIDA/maladies infectieuses, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR MOP-79529), and the CIHR Canadian HIV Trials Network (CTN222). Dr Marina Klein is supported by a “Chercheurs nationaux” career award from the FRQS. Man Wah Yeung is supported by the Canadian Observational Cohort Collaboration (CANOC) Scholarship Program, in partnership with CIHR Canadian HIV Trials Network.

Conflicts of interest

Marina Klein received grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Fonds de recherche du Québec – Santé (FRQS), Réseau SIDA/maladies infectieuses, the National Institute of Health Research, Merck, ViiV Healthcare, Janssen, Gilead, and Schering-Plough; consulting fees from ViiV Healthcare and AbbVie; and lecture fees from ViiV Healthcare and Gilead. Curtis Cooper received grants from Merck and Abbott, consulting fees from Merck and Vertex, and lecture fees from Merck and Roche. Sharon Walmsley received grants, consulting fees, lecture fees, nonfinancial support, and fees for the development of educational presentations from Merck, ViiV Healthcare, GlaxoSmithKline, Pfizer, Gilead, Abbvie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Janssen. John Gill received a grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and personal fees for being a member of the national advisory boards of Abbvie, Gilead, Merck, Janssen, ViiV Healthcare, and Bristol-Myers Squibb. Mark Hull has served as a consultant for Merck, Vertex Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer, Viiv Healthcare, and Ortho-Jansen. He has received grants from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, and he has received payment for lectures from Merck and Ortho-Janssen. Joseph Cox received grants from ViiV Healthcare and Gilead, and personal fees from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck, and Gilead. Ms Yeung, Dr Young, Dr Moodie, Ms Rollet-Kurhajec, Dr Schwartzman and Dr Greenaway report no disclosures.

Ethics approval

The CCC was approved by the community advisory committee of the CIHR Canadian HIV Trials Network, the Biomedical B Research Ethics Board of the McGill University Health Centre (BMB-06-006t), the UBC-Providence Health Care Research Ethics Board (H08-00474), the Institutional Review Board Services, the Conjoint Health Research Ethics Board (20931), the Capital Health Research Ethics Board (CDHA-RS2007-118), the Windsor Regional Hospital Research Ethics Board (07-122-17), Veritas IRB, the Hamilton Integrated Research Ethics Board (06-397), the Comité d'éthique de la recherche du CHUM (2003-1582, SL 03.008-BSP), the Comité d'éthique de la recherche du CHU de Québec (C11-12-153), the Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre Research Ethics Board (252-2008), the Health Sciences North Research Ethics Board (605), the University Health Network Research Ethics Board (06-0629-BE), the UBC-Providence Health Care Research Ethics Board (H08-00474), and the Ottawa Health Science Network Research Ethics Board (2007229-01H).

References

- Remis RS. Modelling the incidence and prevalence of hepatitis C infection and its sequelae in Canada. Ottawa: Public Health Agency of Canada; 2007.

- Shepard CW, Finelli L, Alter MJ. Global epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection. Lancet Infect Dis. 2005;5(9):558–567.

- Ghany MG, Strader DB, Thomas DL, Seeff LB. Diagnosis, management, and treatment of hepatitis C: an update. Hepatology. 2009;49(4):1335–1374.

- Weber R, Sabin CA, Friis-Møller N, Reiss P, El-Sadr WM, Kirk O, et al. Liver-related deaths in persons infected with the human immunodeficiency virus: the D:A:D study. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(15):1632–1641.

- Jacobson IM, Gordon SC, Kowdley KV, Yoshida EM, Rodriguez-Torres M, Sulkowski MS, et al. Sofosbuvir for hepatitis C genotype 2 or 3 in patients without treatment options. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(20):1867–1877.

- Lawitz E, Poordad FF, Pang PS, Hyland RH, Ding X, Mo H, et al. Sofosbuvir and ledipasvir fixed-dose combination with and without ribavirin in treatment-naive and previously treated patients with genotype 1 hepatitis C virus infection (LONESTAR): an open-label, randomised, phase 2 trial. Lancet. 2014;383(9916):515–523.

- Poordad F, Dieterich D. Treating hepatitis C: current standard of care and emerging direct-acting antiviral agents. J Viral Hepat. 2012;19(7):449–464.

- Tedaldi EM, Baker RK, Moorman AC, Alzola CF, Furhrer J, McCabe RE, et al. Influence of coinfection with hepatitis C virus on morbidity and mortality due to human immunodeficiency virus infection in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36(3):363–367.

- Torriani FJ, Rodriguez-Torres M, Rockstroh JK, Lissen E, Gonzalez-García J, Lazzarin A, et al. Peginterferon Alfa-2a plus ribavirin for chronic hepatitis C virus infection in HIV-infected patients. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(5):438–450.

- Sulkowski MS, Sherman KE, Dieterich DT, Bsharat M, Mahnke L, Rockstroh JK, et al. Combination therapy with telaprevir for chronic hepatitis C virus genotype 1 infection in patients with HIV: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159(2):86–96.

- Sulkowski M, Pol S, Mallolas J, Fainboim H, Cooper C, Slim J, et al. Boceprevir versus placebo with pegylated interferon alfa-2b and ribavirin for treatment of hepatitis C virus genotype 1 in patients with HIV: a randomised, double-blind, controlled phase 2 trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13(7):597–605.

- Pearlman BL, Traub N. Sustained virologic response to antiviral therapy for chronic hepatitis C virus infection: a cure and so much more. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(7):889–900.

- Singal AG, Volk ML, Jensen D, Di Bisceglie AM, Schoenfeld PS. A Sustained viral response is associated with reduced liver-related morbidity and mortality in patients with hepatitis C virus. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8(3):280–288e281.

- McHutchison JG, Ware JE Jr, Bayliss MS, Pianko S, Albrecht JK, Cort S, et al. The effects of interferon alpha-2b in combination with ribavirin on health related quality of life and work productivity. J Hepatol. 2001;34(1):140–147.

- Berenguer J, Alvarez-Pellicer J, Martin PM, López-Aldeguer J, Von-Wichmann MA, Quereda C, et al. Sustained virological response to interferon plus ribavirin reduces liver-related complications and mortality in patients coinfected with human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis C virus. Hepatology. 2009;50(2):407–413.

- Berenguer J, Rodríguez E, Miralles P, Von Wichmann MA, López-Aldeguer J, Mallolas J, et al. Sustained virological response to interferon plus ribavirin reduces non-liver-related mortality in patients coinfected with HIV and Hepatitis C virus. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55(5):728–736.

- Myers RP, Liu M, Shaheen AA. The burden of hepatitis C virus infection is growing: a Canadian population-based study of hospitalizations from 1994 to 2004. Can J Gastroenterol. 2008;22(4):381–387.

- Myers RP, Krajden M, Bilodeau M, Kaita K, Marotta P, Peltekian K, et al. Burden of disease and cost of chronic hepatitis C infection in Canada. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;28(5):243–250.

- Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH). Direct-acting antivirals for chronic hepatitis C genotype 1-project protocol. Volume 2, Issue 2A. CADTH Therapeutic Review Report; http://www.cadth.ca/media/pdf/TR0007_HepC_Protocol_e.pdf. Accessed July, 2014 2014.

- Martin NK, Vickerman P, Miners A, Foster GR, Hutchinson SJ, Goldberg DJ, et al. Cost-effectiveness of hepatitis C virus antiviral treatment for injection drug user populations. Hepatology. 2012;55(1):49–57.

- Klein MB, Saeed S, Yang H, Cohen J, Conway B, Cooper C, et al. Cohort profile: the Canadian HIV-hepatitis C co-infection cohort study. Int J Epidemiol. 2010;39(5):1162–1169.

- EuroQol-Group. EuroQol – a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy. 1990;16(3):199–208.

- Klein MB, Rollet KC, Saeed S, Cox J, Potter M, Cohen J, et al. HIV and hepatitis C virus coinfection in Canada: challenges and opportunities for reducing preventable morbidity and mortality. HIV Med. 2013;14:10–20.

- Chen J, Florian J, Carter W, Fleischer RD, Hammerstrom TS, Jadhav PR, et al. Earlier sustained virologic response end points for regulatory approval and dose selection of hepatitis C therapies. Gastroenterology. 2013;144(7):1450–1455e1452.

- Chevaliez S, Pawlotsky JM. Hepatitis C virus serologic and virologic tests and clinical diagnosis of HCV-related liver disease. Int J Med Sci. 2006;3(2):35–40.

- Monto A, Patel K, Bostrom A, Pianko S, Pockros P, McHutchison JG, et al. Risks of a range of alcohol intake on hepatitis C-related fibrosis. Hepatology. 2004;39(3):826–834.

- Nunes D, Fleming C, Offner G, O'Brien M, Tumilty S, Fix O, et al. HIV infection does not affect the performance of noninvasive markers of fibrosis for the diagnosis of hepatitis C virus-related liver disease. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;40(5):538–544.

- Wai CT, Greenson JK, Fontana RJ, Kalbfleisch JD, Marrero JA, Conjeevaram HS, et al. A simple noninvasive index can predict both significant fibrosis and cirrhosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2003;38(2):518–526.

- Al-Mohri H, Murphy T, Lu Y, Lalonde RG, Klein MB. Evaluating liver fibrosis progression and the impact of antiretroviral therapy in HIV and hepatitis C coinfection using a noninvasive marker. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;44(4):463–469.

- Bansback N, Tsuchiya A, Brazier J, Anis A. Canadian valuation of EQ-5D health states: preliminary value set and considerations for future valuation studies. PLoS One. 2012;7(2):e31115.

- Wu AW, Hanson KA, Harding G, Haider S, Tawadrous M, Khachatryan A, et al. Responsiveness of the MOS-HIV and EQ-5D in HIV-infected adults receiving antiretroviral therapies. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2013;11:42.

- Wu AW, Jacobson KL, Frick KD, Clark R, Revicki DA, Freedberg KA, et al. Validity and responsiveness of the euroqol as a measure of health-related quality of life in people enrolled in an AIDS clinical trial. Qual Life Res. 2002;11(3):273–282.

- Unal G, de Boer JB, Borsboom GJ, Brouwer JT, Essink-Bot M, de Man RA. A psychometric comparison of health-related quality of life measures in chronic liver disease. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54(6):587–596.

- Tran BX, Nguyen LT. Impact of methadone maintenance on health utility, health care utilization and expenditure in drug users with HIV/AIDS. Int J Drug Policy. 2013;24(6):e105–e110.

- Pickard AS, Neary MP, Cella D. Estimation of minimally important differences in EQ-5D utility and VAS scores in cancer. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2007;5:70.

- Chong CA, Gulamhussein A, Heathcote EJ, Lilly L, Sherman M, Naglie G, et al. Health-state utilities and quality of life in hepatitis C patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98(3):630–638.

- Razavi H, Elkhoury AC, Elbasha E, Estes C, Pasini K, Poynard T, et al. Chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) disease burden and cost in the United States. Hepatology. 2013;57(6):2164–2170.

- Werb D, Wood E, Kerr T, Hershfield N, Palmer RW, Remis RS. Treatment costs of hepatitis C infection among injection drug users in Canada, 2006-2026. Int J Drug Policy. 2011;22(1):70–76.

- Krajden M, Kuo M, Zagorski B, Alvarez M, Yu A, Krahn M. Health care costs associated with hepatitis C: a longitudinal cohort study. Can J Gastroenterol. 2010;24(12):717–726.

- Grady BP, Schinkel J, Thomas XV, Dalgard O. Hepatitis C virus reinfection following treatment among people who use drugs. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;57(Suppl 2):S105–S110.

- Page K, Hahn JA, Evans J, Shiboski S, Lum P, Delwart E, et al. Acute hepatitis C virus infection in young adult injection drug users: a prospective study of incident infection, resolution, and reinfection. J Infect Dis. 2009;200(8):1216–1226.

- Micallef JM, Macdonald V, Jauncey M, Amin J, Rawlinson W, van Beek I, et al. High incidence of hepatitis C virus reinfection within a cohort of injecting drug users. J Viral Hepat. 2007;14(6):413–418.

- Holmberg SD, Spradling PR, Moorman AC, Denniston MM. Hepatitis C in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(20):1859–1861.

- Langendam MW, van Haastrecht HJ, van Ameijden EJ. The validity of drug users' self-reports in a non-treatment setting: prevalence and predictors of incorrect reporting methadone treatment modalities. Int J Epidemiol. 1999;28(3):514–520.

- Digiusto E, Seres V, Bibby A, Batey R. Concordance between urinalysis results and self-reported drug use by applicants for methadone maintenance in Australia. Addict Behav. 1996;21(3):319–329.

- Weissman JS, Levin K, Chasan-Taber S, Massagli MP, Seage GR 3rd, Scampini L. The validity of self-reported health-care utilization by AIDS patients. AIDS. 1996;10(7):775–783.