Abstract

Objective:

The requirement for formal Continuing Medical Education (CME) is growing in Europe with a concomitant focus on quality and independence of medical educational programmes, together with a need for measurable effects on patient outcomes. However, during this rapid evolution, it has become clear that there are misunderstandings and confusion amongst CME providers in relation to standard and regulations. To address this challenging situation, the Good CME Practice Group undertook an initiative to establish a set of standard core principles with a view to adoption by European CME providers and other key organisations involved in provision of CME programmes.

Methods:

The Good CME Practice Group developed four core principles relating to (a) appropriate education, (b) effective education, (c) fair balance and (d) transparency. In order to seek advice and input from peer groups and others involved in CME including accrediting bodies and medical societies, 93 representatives from these bodies were asked to complete a questionnaire and provide comments on the core principles. Participants for the consultation process were generated by a systematic search for European organisations with sections committed to medical education across all therapy areas and all key accrediting bodies. Following the consultation phases, the core principles were reviewed in light of responses and feedback and amended as appropriate.

Results:

The response rate amongst invited participants was 42% and similar across all groups with the exception of European medical societies. However, despite this limitation, there were significant levels of endorsement of the principles by all stakeholders with 90–95% recommending adoption of principles relating to appropriate education, fair balance and transparency. The principle relating to the measure of effective education was also highly endorsed with 89% of respondents recommending uptake. In response, however, to some questions relating to feasibility of implementation, the principle was revised accordingly. Overall, the stakeholders have recommended uptake of all core principles.

Conclusions:

The overall goal of the Good CME Practice Group is to guide how European CME providers contribute to improving public health outcomes by championing best practice in CME, maintaining and improving standards, mentoring and educating and working in collaboration with critical stakeholders. The significant endorsement of the four core principles has confirmed that this is a timely and well-received initiative that is aligned with the objectives of key organisations involved in provision of CME-accredited programmes. The Good CME Practice Group will continue to have dialogues with CME accreditation authorities, regulatory bodies and other key stakeholders in order to facilitate collaboration in improving standards across Europe.

Introduction and objectives

Continuing Medical Education (CME) in Europe is evolving rapidly with an increasing number of countries adopting voluntary or mandatory systems of CME participation for their physiciansCitation1 as evidence mounts that good CME programmes improve clinical practice and outcomesCitation2,Citation3. The requirements of educational programmes are also changing rapidly, particularly with a need for clear demonstration that a CME-accredited activity has been developed independently by a faculty, meets educational needs, is free from bias and is of high qualityCitation4.

The Good CME Practice Group consists of 12 European non-society education providers with shared objectives. It convened following the 2nd European CME Forum meeting in 2009 in response to a growing body of concern around misunderstandings and abuses that were becoming increasingly apparent in European CMECitation5, where organisations without CME experience were both receiving funding for developing CME programmes, and also submitting what the Group considered to be sub-standard programmes for accreditation. The problems were exemplified by the fact that there was general confusion about the types of organisation that can be involved in European CME, which standards should be followed, and how they should be implemented. There has been a general perception that there has been a lack of clarity in the regulations and guidelines of European CMECitation6,Citation7, with the eventual result of ‘poor’ quality in some CME programmes. Consequently, there is a need for the CME accreditation bodies to revise their guidance and clarify potentially nebulous areas such as transparent declarations of the role of all the parties involved and bias where industry support is involved, which is becoming an ever increasing difficult task. This is currently in process with UEMS-EACCME further revising their updated accreditation standardsCitation8,Citation9 for implementation in early 2013. Industry in Europe is also examining how to put in place clearer guidelines for how they support CME activitiesCitation6.

It is the general view that most funding for CME comes from industryCitation6,Citation10. However for this to be acceptable, it is essential that there are clear and transparent guidelines to ensure the quality and credibility of the educational materials being developed, and to eliminate any negative perception, that may or may not be justified.

The Good CME Practice Group has a common desire to improve the quality of medical education for learners, especially relating to fair balance, transparency and the general relevance and effectiveness of the education in improving clinical practice. It agreed that providers needed to demonstrate that they are adhering to the required standards in order to demonstrate to the accreditation bodies, as well as potential financial supporters from industry, that there is a distinct group of providers that is knowledgeable and competent in the development and delivery of a CME-accredited educational programme. Thus the Good CME Practice Group works in an independent and complementary manner to support the accrediting bodies in their desire for high quality and appropriate independent education.

The goal of this initiative was to establish a set of core principles as a standard to act as guidelines to encourage the uptake amongst all stakeholders to (a) improve quality of CME programmes in Europe and (b) to support all parties and users striving to improve programmes.

The objective of this study was to test these core principles among key stakeholder groups across Europe who would be interacting with those providers who would be using these principles to guide their own activities. Positive results of this consultation would inform the Group to develop a checklist to guide providers on implementation of standards. It is widely recognised that setting guidelines as a unilateral activity is not necessarily enough to ensure adoption and the Group recognises the success of the updated Good Publication Practice guidance developed for the publication of company-sponsored medical researchCitation11, and how it has gained widespread acceptance and adoption. In order to ensure the final guidelines developed would be of highest relevance to the audience, thus promoting the highest chance of adoption, the following provisions were incorporated:

To liaise with key stakeholder groups in European CME at each stage of development of the core principles to ensure alignment with their regulatory, legal and operational expectations. These stakeholders comprise members of the CME accreditation bodies, medical societies and pharmaceutical company financial supporters.

To validate the guidelines through a formal consultation process with the ultimate target audience (through the European and national medical societies) and the CME accreditation bodies themselves.

Ensure that all recommendations are clear and practical in today’s CME environment.

Methods

Development of core principles

In November 2009, the Founding Members of the Good CME Practice Group presented the concept of six core principles to drive standards in Europe to delegates attending the European CME Forum in LondonCitation5. Subsequently in response to discussions, the Group further refined these principles, distilling them down to four main core principles relating to appropriate education, balance, transparency and effectiveness of education. Although there was extensive discussion around the benefits of a core principle relating to quality, it was agreed that since quality is determined by all these factors, a separate principle was not required. Consideration was also given to including a requirement for independent peer review (of performance gaps, scientific content and educational design). However, it was felt that it was the role and responsibility of the accrediting bodies to provide this quality control.

Consultation phase

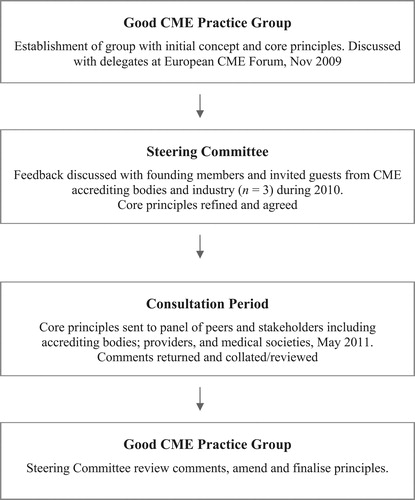

Drafts of the core principles were tested during a consultation phase () with key stakeholders in European CME. The consultation involved participants from a range of organisations including national and European accreditation boards and medical societies across Europe. Participants were selected following a systematic search for medical organisations in all recognised specialities that had a demonstrable commitment to CME, in addition to regulatory bodies within Europe, and individuals with a position within CME-related functions, such as medical educators in academia. Participants were drawn from senior individuals in these organisations who were either able to represent their organisation or education committee. Questionnaires were available for completion on-line, by email or in hardcopy. Participants were given 6 weeks to respond with follow-up with non-responders after 3 weeks. Of 93 participants approached, complete responses were received from 39 organisations (42%).

Participants in the consultation process were asked to comment on each individual principle in terms of whether it would set an appropriate standard, whether implementation of the principle is feasible and whether application of the principle is likely to improve the quality of education.

Respondents were also asked to state (yes/no) whether they would endorse adoption of each principle by all parties involved in providing CME programmes, including financial supporters, accrediting bodies, providers and faculty. Comments were invited as to which considerations informed their decision or when participants wanted to raise specific points for consideration.

All correspondence was conducted in confidence.

Analyses

A blinded analysis was performed on data by a subgroup of the Steering Committee members and presented to the wider group for discussion and ratification.

All comments from the consultation were reviewed with the results of the analysis by the Steering Committee. This information was used to guide the panel as to whether a principle was generally acceptable as drafted, or amendment was required.

At no time were individual respondents identified in relation to responses and comments.

Core principles and response to consultation

Participation

Comments were invited from 93 stakeholders and peers in 18 countries with 39 responses received. All responses were validated against the inclusion criteria that the consulting body should be a CME-accrediting body involved at pan-European or national levels, European and national medical societies or European university departments active in CME. One response was excluded on the basis of being incomplete.

Of the responses, 16 (41%) were from European specialty accreditation boards, 14 (36%) from National accreditation authorities, two (5%) from European medical societies and seven were received from national medical societies (18%). Approximately, 80% of European and national accrediting bodies responded and almost 40% of national medical societies. Among European medical societies, only two responses were received from 32 invitations.

Results

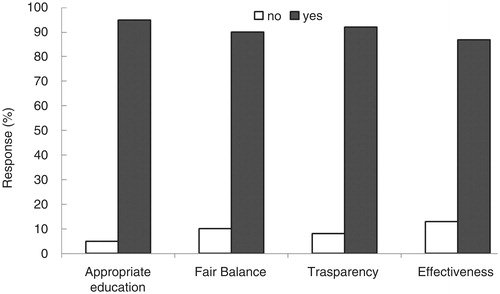

Overall, there were significant levels of endorsement of the principles by all stakeholders with 95%, 90% and 92% recommending adoption of principles 1, 2 and 3, respectively by all involved in provision of CME programmes (). A large majority (87%) also endorsed adoption of principle 4. Overall, responses were similar between types of organisation.

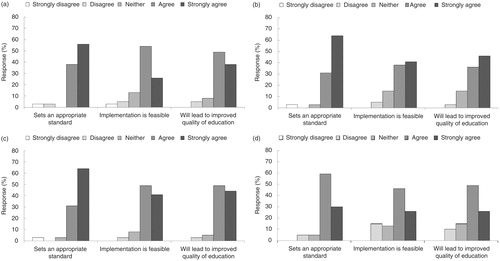

shows more detail of responses relating to each principle.

Figure 3. Response to consultation phase of core principles relating to (a) appropriate education, (b) fair balance, (c) transparency and (d) effectiveness.

Appropriate education

Draft: CME providers should ensure that educational activities have clear learning objectives that are derived from a coherent and objective process that has identified performance gaps and unmet educational needs. The education must be designed to positively reinforce existing good practice and effect a sustained change in daily clinical practice as appropriate.

This principle was particularly well received with 94% of respondents agreeing or strongly agreeing that it sets an appropriate standard (). A similar proportion (87%) agreed that the principle would lead to improved quality of education. Notably, 80% of respondents agreed or strongly agreed that implementation of the principle was feasible with 13% neither agreeing nor disagreeing.

Of respondents that did not agree with the principle, 5–6% either disagreed or strongly disagreed that the principle set an appropriate standard or would lead to improved quality of education. Slightly more respondents (8%) disagreed that implementation of the principle was feasible.

Recommendation

Few respondents commented on this principle but amongst comments received was one stating that performance of a formal gap analysis for all educational activities was not always feasible or necessary, for example, in the context of Continuing Professional Development (CPD) rather than CME. Other feedback noted that the focus should be on individual learners’ needs that can only be identified by the learner themselves.

However, accreditation guidelines from the European Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical EducationCitation4,Citation8,Citation9 require details for educational activities on how a needs assessment was performed together with a demonstration of how educational objectives were derived from that assessment. This requirement, combined with the aim of the Good CME Practice Group to provide a set of guiding principles that would set the highest standard of best practice, persuaded the Steering Committee to keep reference to a gap analysis in the principle. The group expected that learners’ participation in accredited education would be based on self-identified needs that would usually include input from managers.

On this basis and given the level of support for this principle, the Steering Committee agreed that this principle was acceptable as drafted.

Fair balance

Draft: Balance needs to be evident in content, faculty and review. Content has to be developed independently of the sponsor and reflect the full clinical picture within the framework of the learning objectives.

Response to this principle in relation to setting an appropriate standard stimulated a high level of endorsement of 90%. Similar high levels of agreement were achieved in relation to feasibility of implementation (90%) and likely impact on quality of education (93%).

Only 3% either disagreed or strongly disagreed with any statement regarding this principle.

Recommendation

A challenge to this principle was received in the consultation phase highlighting that financial support for educational programmes is not exclusively the domain of pharmaceutical companies but could be a medical society, academic institution or similar. In this situation, it is likely to be appropriate for the supporter to be involved in programme and content development. The Steering Committee considered this feedback but felt that it is essential for the perception, credibility, integrity and success of CME programmes that content must be developed independently of all commercial organisations and their interests such that patient interests take precedence. Therefore, given the strong overall endorsement by participants in the consultation, the consensus of the group was to let the principle stand as drafted.

Transparency

Draft: All relevant information should be disclosed to the learner so that they understand fully how the content has been developed and presented. This includes the terms of the financial support, relevant disclosures of faculty and organisations involved in the development of the scientific content, and the presentation of the programme.

Approximately two-thirds of respondents strongly agreed that this principle sets an appropriate standard and a further 31% agreed with this point. There was good agreement (82%) that this principle would lead to improved quality of education although 15% were undecided. Similarly, 79% agreed or strongly agreed that implementation of the principle was feasible with 15% neither agreeing nor disagreeing.

As with the principle relating to balance, few respondents (3–5%) disagreed with this principle with respect to appropriate standard, feasibility of implementation or potential to improve quality of education.

Recommendation

Responses during the consultation phase and additional comments consistently reflected concerns about the feasibility of full transparency rather than its desirability. For example, more than one of the participating bodies suggested that the current system did not allow for sufficient transparency (for example, the tendency to show disclosures briefly on an opening slide) and that all organisations involved in an accredited activity should disclose their experience in educational programmes.

Based on these comments and the general feedback, the Steering Committee recommended that the drafted wording of the principle should be accepted.

Effectiveness

Draft: Post-activity evaluation should measure satisfaction, knowledge uptake and intent to maintain or change behaviour in line with learning objectives. Providers should measure the effectiveness of the education against ‘Level 3 - Knowledge Gain’ of the Moore scaleCitation12, which should be seen as a minimum standard.

Of the four core principles, the measure of effectiveness proved most controversial. There was still a high level of agreement (89%) that the principle set an appropriate standard but more people agreed (59%) rather than strongly agreed (30%). A further 5% disagreed while 5% were undecided.

Asked to feedback as to whether implementation of the principle was feasible, 72% gave positive responses. Notably, 15% disagreed and a further 13% neither agreed nor disagreed. Similar feedback was received on the question of the principle leading to improved quality of education with 75% agreeing, 10% disagreeing and 15% undecided. Despite some perceived challenges around this principle, 87% of respondents endorsed adoption.

Recommendation

A number of comments were received for this principle. A consistent point was that while acknowledging that a measure of effectiveness was necessary, this can be ‘difficult to implement’ as not all users completed an evaluation form. Others noted that it is ‘not very realistic’ and questioned whether ‘measurement against the Moore scale is necessary’ while some preferred the emphasis to be on assessing learner satisfaction. On reviewing the comments and data showing overall that there were doubts about the feasibility of implementation and likely impact on quality of education, the Steering Committee felt that the principle should be reworded. In particular, reference to the Moore scale was to be removed.

Revised principle:

Post-activity evaluation should measure satisfaction, knowledge uptake and intent to maintain or change behaviour in line with learning objectives.

To facilitate implementation of the core principles and ensure consistency of approach, the Good CME practice group have developed a checklist to guide providers through the fundamental processes in effective CME ().

Discussion

The goal of the members of the Good CME Practice Group is to contribute to improving the quality and effectiveness of medical education through implementation of rigorous, yet practical, standards for the development of CME programmes in Europe. There was a good participation rate amongst all the types of organisations approached with the exception of European Medical Societies. Given that there was a reasonable response rate amongst national medical societies, the authors feel that, at this time, the disappointing response from European medical societies most likely reflects the difference in level of engagement with CME provision within Europe. Of the respondents, there was a high level of response to our consultation phase (39 participants provided comments) and strong endorsement for adoption of the core principles (∼90%) with no difference in responses between types of participating organisations.

Overall, the Group feels that this consultation process has confirmed that this is a very timely and well-received initiative that is aligned with the objectives of all parties involved.

Independence and transparency

At the time of inception of the Group, it was clear that there was a significant level of disquiet amongst most parties involved in provision of, and use of, CME in relation to the quality and independence of programmes. To a large extent, this reflects concerns around bias of programmes due to industry support. Indeed, in a recent US survey, 88% of participants believed that industry-derived financial supported CME activities were subject to biasCitation13. Other research from Germany and the US has indicated that industry-funded CME programmes are statistically equivalent to non-commercially supported CME activities in the degree of detectable bias presentCitation14,Citation15, underscoring the point that there are numerous potential sources of bias, that include intellectual and professional as well as financial biases. This point was recently acknowledged by the European Society of Cardiology in their CME policy document, which concluded that financial sources of bias must be acknowledged by full disclosureCitation16. It is worth noting, nevertheless, that the relationship of perceived bias to actual bias is poorly understood as the difficulty of measuring actual bias has led to a paucity of studies in this areaCitation15,Citation17.

Core principles around ‘fair balance’ and ‘transparency’ were developed to address the challenges of potential and perceived bias in educational activities and were most robustly supported and endorsed by those in the consultation phase. A key component of the ‘balance’ principle is that ‘content must be developed independently of the sponsor’. Although this may be a self-evident means to avoid bias or undue influence, some accrediting bodies in Europe (particularly at national level) still allow significant input into content by the commercial supporter. However, the Good CME Practice Group feels very strongly that this should change and, where there is a lack of clarity in the regulations, this should be rectified by further discussion and engagement with the appropriate accrediting bodies. Moreover, the authors recommend that there is increased monitoring of programmes and sanctions applied where necessary.

While most people and organisations involved providing CME strive to produce high quality, objective and unbiased programmes, ultimately, the user/learner should be in a position to assess this for themselves. They can only make informed decisions, however, if they are in full possession of information relating to potential conflicts of interest. Scientific and medical journals have tended to be at the forefront of requiring comprehensive declarations of potential conflicts of interest and have defined conflicts of interest in relation to authors and financial supporters of publicationsCitation11,Citation18.

In a similar manner, both faculty and providers of CME-accredited programmes should provide full disclosures of any personal conflicts of interest in addition to a clear declaration of source and terms of funding with details of their relationship, if any, with the funding organisation. Learners should always be given the opportunity to report bias (perceived or real) through evaluation and feedback forms (provided at the point of learning).

While making learners aware of potential conflicts of interest is fundamental, it is also the responsibility of parties involved in the development of the content to address such conflicts as early as possible in the programme development. It is essential that content is evidence-based medicine (with only appropriate levels of evidence included), a balanced view of any therapeutic approach is presented and that any guidance given reflects consensus opinion from the medical community. All stakeholders involved in content development or presentation must agree and align with these concepts at the initial stages of the activity. If for any reason any party feels unable to do this, then consideration should be given to asking them to withdraw.

Appropriate and effective education

The goal of CME (and CPD) is to improve patient care through improved clinical performance of healthcare professionals translating into improved clinical outcomes. Evidence indicates that a major contributor to achieving this goal is a formal assessment of educational needs of the target audienceCitation19–21. A requirement for a needs assessment is embodied in the first core principle of appropriate education and should give rise to learning objectives for the activity. The authors felt that it was important to crystallise the need to reiterate that course content encompasses current best practice and standard of care at this point.

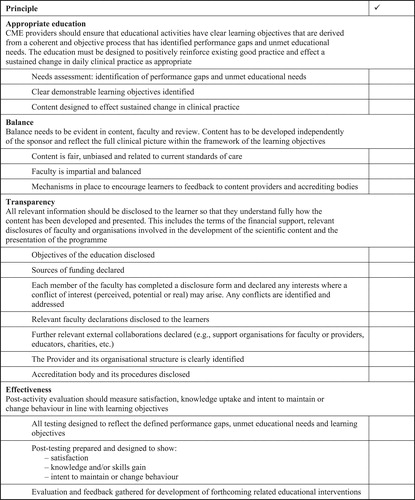

Table 1. Core principles to be adopted following consultation.

There has been extensive debate over many years as to the how to measure educational outcomes and assess the effectiveness of CME and yet, the results of an extensive and systematic literature search reveal few publications on this subjectCitation2,Citation22–24. Undoubtedly, in many cases, assessment of some CME activities is more a measure of participation than learning or assessment of knowledge gain through correct completion of multiple choice questions (that are not always robustly designed). Ideally, since the goal of CME is to improve clinical care and patient outcomes, this should be the primary outcome measurement. Haynes et al.,Citation22 reported a systematic analysis of 248 original articles relating to evaluation of CME. While 38% of studies measured change in clinical performance, only 7% of studies assessed the impact on patient outcomes. The authors note the challenge of measuring changes in patient outcome when this can be affected by many factors including patient-related delays in seeking medical care etc. This is particularly pertinent to this analysis since the studies reviewed were conducted predominantly in primary care. A subsequent analysis of the literature relating to CMECitation2 found that only 50/777 were randomised controlled trials that measured physician performance and/or health outcomes. Findings of this study highlighted the complexity of developing CME programmes that can improve patient outcomes noting that enabling interventions were more effective that predisposing interventions. It was also noted that there was a lack of a robust association between change in physician performance and patient outcome. This lack of clear relationship is likely to be due at least in part to confounding factors such as non-adherence to medications or even by therapy area (e.g., hypertension) where improvements are difficult to measure as there is often relatively good control and management. A recent study is more robust and has been able to show an association between learning programmes in primary care and decreased mortality due to coronary heart diseaseCitation3. This prospective, randomized, controlled trial assessed the effect of repeated case-based education of primary care practitioners on mortality. The interventions centred on regularly updating and distributing guidelines for lipid-lowering management combined with attendance at 1–2 case seminars/year over a 2-year period. At the end of the study period, mortality in the intervention group was 22% compared to 44% in the control group.

However, it remains difficult to get true measures of effective learning outside of a healthcare system for a number of reasons. Principal amongst these is the difficulty and expense of trying to measure change in behaviour or patient outcomes. Performance improvement CMECitation25 has attempted to address measurement of change in clinical behaviour with a step in the assessment that assesses the user after an interval of time. However this presents some challenges in terms of ensuring physician participation in the follow up particularly when there is no incentive for them to do. This is evident from the recent report from the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME) in the USCitation26, showing that in 2011 only 0.75% of the total CME accredited programmes (by number of hours) were classed as Performance Improvement CME.

A further challenge to measuring effective learning beyond the immediate MCQ assessment is that expectations of changing behaviour can be unrealistic when discussed in the context of a single event or 1-hour online course. Extensive consideration was given, therefore, to the final principle as regards how much guidance should be provided in terms of measurement of outcome. It was thought that at this time, that not only is it difficult to measure change in patient care but the Group felt that a physician’s manager or peer group were best placed to review a physician’s progress following CME activities. The Group would recommend that participation in, and learning from, such CME activities become a component of the formal review system in all countries.

The first draft of the principle included reference to the Moore scale as an objective measure of successful learningCitation12. However, in the consultation process, this proved to be the most contentious principle with comment that this was not feasible for many and that there was a trend towards assessment of level of satisfaction as an adequate/realistic measure. The Steering Committee felt, however, that while it would remove reference to the Moore scale, it was important to recommend that, in addition to assessment of user satisfaction and knowledge uptake, a measure of intention to maintain or change behaviour was essential and should be included as such in all evaluations. Further research on novel, practical and affordable ways to assess change in practice may help to identify reasonable methods for achieving more meaningful evaluations and driving improvements in education standards.

Conclusion

In summary, the overall goal of the Good CME Practice group is to provide guidance on how European CME providers can contribute to improving clinical care. The group aims to do this by championing best practice in CME, maintaining and improving standards, mentoring and educating and working in collaboration with critical stakeholders. By this means, CME programmes should be better targeted to address true educational needs of learners. Moreover, improved design of initiatives will lead to effective education that translates to positive changes in the clinical practice of users.

Key to success of this is to ensure that the core principles developed in this initiative relating to (a) appropriate education, (b) effective education, (c) fair balance and (d) transparency are recognised and implemented by all involved in the CME arena along with continued research efforts in the impact of these principles on practice. While the disappointing response rate from European medical societies is a limitation of this consultation, the authors feel that the consistent feedback and the strength of support for this initiative from other participants indicates that the core principles are sufficiently robust. However, the Group will continue to engage with European medical societies together with CME accreditation authorities, regulatory bodies and other key stakeholders. The Good CME Practice Group has initiated a broadening of membership to include more organisations, especially European medical societies that will uphold these principles. This broader membership will facilitate continued interaction with CME stakeholders and provision of further guidance on how to engage with CME projects in Europe.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This study was funded by the Good CME Practice Group.

Declaration of financial/other interests

The authors have no relevant financial relationships to disclose. CMRO peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

Notice of Correction

The version of this article published online ahead of print on 26 October 2012 contained an error on page 6. The paragraphs in the sections ‘Fair Balance’ and ‘Transparency’ were transposed. The error has been corrected for this version.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the following people for their contributions to the concept, development and/or implementation of this initiative: Edwin Borman, Thomas Kellner, Peter Llewellyn, Carry Pesch, Chris Stevenson, Robin Stevenson and David Williams.

References

- Weisshardt I, Stapff I, Schaffer M. Increased understanding of medical education pathways in Europe as a potential quality factor in CME – a comprehensive assessment of the current landscape. J Eur CME 2012;1:9-17

- Davis DA, Thomson MA, Oxman AD, et al. Evidence for the effectiveness of CME. A review of 50 randomized controlled trials. JAMA 1992;268:1111-17

- Kiessling A, Lewitt M, Henriksson P. Case-based training of evidence-based clinical practice in primary care and decreased mortality in patients with coronary heart disease. Ann Fam Med 2011;9:211-18

- European Union of Medical Specialists (UEMS). Criteria for international accreditation of CME (D9908 rev 2007). Accessed at http://www.uems.net/fileadmin/user_upload/uems_documents/contentogram_doc_client_20120530/D9908rev2007.pdf

- Pozniak E, Williams D. 2nd Annual Meeting of the European CME Forum. February 2010. Accessed at http://www.KeywordPharma.com

- First Word, Pharma’s Future Role in CME. August 2012. Doctor’s Guide Publishing Limited. Accessed at: http://www.fwreports.com

- Pozniak E, Williams D. 3rd Annual Meeting of the European CME Forum. February 2011. Accessed at http://www.KeywordPharma.com

- European Union of Medical Specialists (UEMS). The accreditation of e-learning materials by the EACCME (UEMS 20122/20). Accessed at http://www.uems.net/fileadmin/user_upload/uems_documents/contentogram_doc_client_20120530/UEMS_2011_20.pdf

- European Union of Medical Specialists (UEMS). The accreditation of live educational events by the EACCME (UEMS 2011/30). Accessed at http://admin.uems.net/uploadedfiles/1497.pdf

- Villanueva T. Spanish campaign endorsing independent medical education and training gains momentum CMAJ 2011;183: E93-6. Accessed at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3033949/

- Graf C, Battisti WP, Bridges D, et al. Research methods & reporting. Good publication practice for communicating company sponsored medical research: the GPP2 guidelines. BMJ 2009;339:b4330 doi: 10.1136/bmj.b4330

- Moore DE, Green JS, Gallis HA. Achieving desired results and improved outcomes: integrating planning and assessment throughout learning activities. J Contin Educ Health Prof 2009;29:1-15

- Tabas JA, Boscardin C, Jacobsen DM, et al. Clinician attitudes about commercial support of continuing medical education: results of a detailed survey. Arch Intern Med 2011;171:840-6

- Chon SH, Lösche P, Christ H, Lehmacher W, Griebenow R. [Comparative evaluation of sponsored and unsponsored continuing medical education]. Med Klin (Munich) 2008;15;103:341-5 [German]

- Kawczak SMA, Carey, Lopez R, Jackman D. The effect of industry support on participants’ perceptions of bias in continuing medical education. Acad Med 2010;85:80-4

- European Society of Cardiology. Relations between professional medical associations and the health-care industry, concerning scientific communication and continuing medical education: a Policy Statement from the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J 2012;33:666-4. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr480

- Cervero RM, He J. The relationship between commercial support and bias in continuing medical education activities: a review of the literature. Accreditation Council for CME. June 2008. Accessed at http://www.accme.org/news-publications/news/6112008-review-literature-relationship-between-commercial-support-and-bias

- Caplan AL. Halfway there: the struggle to manage conflicts of interest. J Clin Invest 2007;117:509-10

- Grant J. Learning needs assessment: assessing the need. BMJ 2002;324:156.

- Norman GR, Shannon SI, Marrin ML. The need for needs assessment in continuing medical education. BMJ 2004;328:999.

- Cochrane LJ, Olson CA, Murray S, et al. Gaps between knowing and doing: understanding and assessing the barriers to optimal health care. J Contin Educ Health Prof 2007;27:94-102

- Haynes RB, Davis DA, McKibbon A, Tugwell P. A critical appraisal of the efficacy of continuing medical education. JAMA 1984;251:61-4

- Davis D, Bordage G, Moores LK, et al. The science of continuing medical education: terms, tools, and gaps: effectiveness of continuing medical education: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Educational Guidelines. Chest 2009;135(3 Suppl):8-16S

- Davis D. Can CME save lives? The results of a Swedish, evidence-based continuing education intervention. Ann Fam Med 2011;9:198-200

- Kahn, N. Performance improvement CME: Core of the new CME. AMA 2007. Accessed at www.ama-assn.org/resources/doc/cme/cppd22.pdf

- Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME) 2011 Annual Report Data. July 2012. Accessed at http://accme.org/sites/default/files/null/630_2011_Annual_Report_20120724.pdf