Abstract

Objective:

To evaluate fracture risk and bone mineral density (BMD) in patients with primary osteoporosis, 1 year after completing 72 weeks of weekly teriparatide injections.

Research design and methods:

After 72 weeks of teriparatide injections or placebo (original trial), treatment was unblinded and subjects were subsequently treated with bisphosphonates or other therapeutic regimens at the discretion of their physicians and followed for 1 year. Spine radiographs and BMD measurements at the lumbar spine, femoral neck, and total hip by dual energy X-ray absorptiometry were performed.

Main outcome measure:

Incident vertebral fracture rate.

Results:

A total of 465 patients were enrolled and 447 (96.1%) completed the study. In the 1 year follow-up period, new morphometric vertebral fractures occurred in 7/203 (3.4%) in the post-teriparatide group and 33/241 (13.7%) in the post-placebo group (relative risk [RR]: 0.23, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.10 to 0.52, P < 0.05). The cumulative incidences from the start of the original trial were 4.9% and 22.8%, respectively (RR: 0.18, 95% CI: 0.09 to 0.36, P < 0.05). There were no significant differences in incidences of vertebral fractures between subsequent therapeutic regimens in the post-teriparatide group. In subjects treated with bisphosphonates, mean BMD values further significantly increased by 9.6%, 2.9%, and 4.1% at the lumbar spine, femoral neck, and total hip, respectively (P < 0.05).

Conclusions:

The reduced risk of vertebral fracture was sustained for 1 year after completion of 72 weeks of weekly teriparatide injections. The effects did not differ between subsequent therapeutic regimens. BMD gains continued with sequential bisphosphonate treatment, but not with the other sequential therapeutic regimens. Bisphosphonates seem to be a useful choice as a subsequent treatment to weekly teriparatide.

Limitation:

This study was an observational follow-up study and the regimens of subsequent medication after discontinuation of the original TOWER trial were not randomly allocated.

Introduction

Osteoporosis is a chronic disease affecting both men and womenCitation1 with an increased risk of fracture from compromised bone strength, mainly due to low bone mass and micro-architectural deteriorationCitation2,Citation3. The incidence of vertebral fracture, the most common fracture in osteoporosis, increases markedly with age and low bone mineral density (BMD), particularly in individuals with prevalent vertebral fracturesCitation4–6. A treatment strategy for the long-term care of individual patients with osteoporosis is necessaryCitation7,Citation8. Teriparatide, whether synthesized chemically (hPTH 1-34) or by recombinant DNA technology (rhPTH 1-34), has an anabolic action on the skeleton to increase bone mass and improve bone micro-architecture when administered subcutaneously in an intermittent manner. Once-daily injections of 20 μg rhPTH 1-34 have been shown to potently increase BMD and reduce the risk of fracture in postmenopausal women and men with osteoporosis by increasing bone formation and resorptionCitation9–12. Recently, another regimen of teriparatide treatment, a weekly subcutaneous injection of hPTH 1-34 (56.5 μg), has been proven effective at increasing BMD and reducing the risk of vertebral fracture by increasing bone formation and reducing bone resorption in postmenopausal women and older men with osteoporosis and prevalent vertebral fractureCitation13.

Because use of teriparatide injections is approved for only 18 to 24 months, it is important to consider whether anti-osteoporotic therapy is necessary to sustain the reduced risk of fracture and maintain the gains of bone mass achieved with teriparatide. After withdrawal of daily teriparatide injections, bisphosphonate therapy has been shown to be effective for maintaining BMD gainsCitation14,Citation15, and subsequent administration of raloxifene prevented rapid loss of lumbar spine BMD and increased femoral neck BMD in postmenopausal women with osteoporosisCitation16. Therefore, antiresorptive agents are effective in maintaining BMD in patients previously treated with daily teriparatide injections. Sustained vertebral and nonvertebral fracture risk reductions after discontinuation of teriparatide have been reported in the Fracture Prevention Trial follow-up studyCitation17,Citation18. The efficacy of sequential bisphosphonate treatment after discontinuation of teriparatide on BMD and vertebral fracture has also been observed in men with osteoporosisCitation15. However, a sustained effect on vertebral fracture risk reduction and BMD after discontinuation of weekly teriparatide injections has not yet been explored.

The purpose of this study was to evaluate patients with primary osteoporosis who had been treated with weekly injections of teriparatide for 72 weeksCitation13 then sequentially given bisphosphonates or other therapeutic regimens such as raloxifene or alfacalcidol for 1 year.

Patients and methods

Original trial subjects and treatment

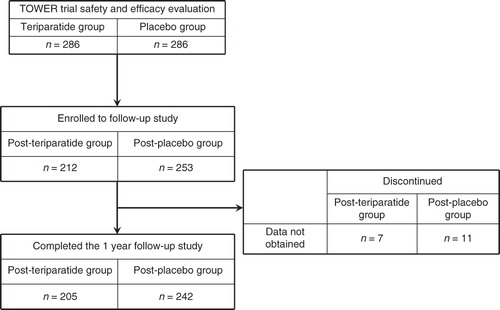

The Teriparatide Once-Weekly Efficacy Research (TOWER) trial enrolled 578 subjects including postmenopausal women and older men with primary osteoporosis and prevalent vertebral fracture who were randomly assigned to weekly subcutaneous injections of teriparatide (56.5 μg) or placebo for 72 weeks as previously reportedCitation13. Efficacy and safety were evaluated in 572 subjects (). All subjects received supplemental calcium (610 mg) and vitamin D (400 IU) daily. Briefly, the subjects were 65 to 91 years old (mean age 75.3 years) and the mean T-scores for BMD at baseline were −2.7 for the lumbar spine (L2–L4), −2.4 for the femoral neck, and −2.1 for the total hip.

Follow-up study

Of the 572 subjects evaluated in the original trial (TOWER), 465 (81%) were enrolled in the follow-up study, preplanned at the start of the TOWER trial (). This follow-up study was started after subjects were evaluated for endpoints including new vertebral fracture and BMD at the end of the original trial in an un-blinded manner. The subjects were grouped according to the post-teriparatide group or post-placebo group, depending on their randomization in the original trial. Although the primary goal of the follow-up study was safety surveillance, radiographs of the thoracic and lumbar spine were obtained and BMD measurements were made at the 1 year follow-up visit.

At the end of the TOWER trial, subjects and physicians were unblinded to the treatment groups. Thereafter, the subjects were entered into the follow-up study and treated at the discretion of their physicians according to standard clinical practice or subjects’ will, including the elective use of other osteoporosis therapies. Calcium and vitamin D supplements were used at the discretion of the subjects and physicians during the follow-up study. The TOWER trial and the follow-up study were approved by the institutional review boards at each site and complied with the Declaration of Helsinki; subjects gave written informed consent for participation.

Vertebral fractures

Radiographs of the thoracic and lumbar spine were used for the assessments of vertebral fracture, taken at the baseline of the TOWER trial, at the end of the TOWER trial (after 72 weeks of treatment with weekly teriparatide or placebo), and then at the end of the 1 year follow-up study. Thus, the incidences of vertebral fracture were obtained at the end of the 1 year follow-up study from the end of the original trial and from the start of the original trialCitation13. The incidences were also evaluated based on the follow-up therapeutic regimens (two groups), either bisphosphonates or other therapeutic regimens such as raloxifene, alfacalcidol, or other clinical therapeutics. Briefly, the vertebral bodies from Th4 to L4 were assessed using both the semiquantitative (SQ) and quantitative morphometric (QM) methods, as reported previouslyCitation19. The assessment of incident vertebral fractures was conducted by an independent committee of three experts who were blinded to treatment. In cases of disagreement between the two methodologies, a binary SQ assessment was conducted by independent experts to adjudicate the discordant result. New vertebral fracture was defined as a vertebral fracture that was normal (SQ grade 0) at baseline of the original trial.

Bone mineral density

BMD of the lumbar spine and hip was measured using dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) at the start of the TOWER trial and at the start and the end of the 1 year follow-up study. The densitometry data were reviewed by an independent committee of experts who were blinded to treatment as described in the original trialCitation13.

Statistical analyses

Incidences of new vertebral fractures in the 1 year follow-up study between the post-teriparatide and post-placebo groups were compared using the Cox regression model. The cumulative incidences of new vertebral fracture at the 1 year follow-up study from the start of the original trial were also assessed using the first-time incidence. An unadjusted Cox regression model was used to estimate the relative risk (RR) and the 95% confidence interval (CI) was calculated (α = 0.05). The incidences of vertebral fractures between the two subsequent therapeutic regimens in the post-teriparatide group were compared using a χ2 test. For BMD data, the means of the percentage changes and 95% CIs were described and the values of percentage changes from the start of the original trial were evaluated by applying the paired t-test in the post-teriparatide group, by subsequent therapeutic regimen. The differences between the post-teriparatide and post-placebo groups were compared by subsequent therapeutic regimen at the start and end of the follow-up study using Student’s t-test. The significance level was set at P < 0.05.

Results

Subjects

Four hundred and sixty-five subjects were enrolled in the follow-up study at 63 sites; 447 (96.1%) completed the study (). There were no differences in the baseline characteristics of the subjects who enrolled in the follow-up study versus those who did not other than age; those who enrolled were younger than those who did not enroll. Although the mean age difference was approximately a year and a half, it was a statistically significant difference (75.0 ± 5.6 vs 76.6 ± 6.4 years, P < 0.05). There were 205 subjects in the post-teriparatide group and 242 in the post-placebo group. The average follow-up periods were 1.0 ± 0.1 year (SD) for both groups. No clinically remarkable symptoms or findings suggesting the occurrence of bone tumor such as localized skeletal swelling and pain were observed. Baseline characteristics at the start of the original trial did not significantly differ between the two groups (). No differences were observed in the background parameters at the start of the follow-up study between the post-placebo and post-teriparatide groups in each subsequent therapeutic regimen (). The proportions of subsequent bisphosphonate use were 34.6% (71/205) in the post-teriparatide group and 35.1% (85/242) in the post-placebo group. The subsequent therapeutic regimens in the follow-up study are shown in . Subjects treated with subsequent bisphosphonates were significantly younger (74.8 ± 5.1 vs 77.1 ± 5.7 years, P < 0.05) and had lower lumbar spine BMD (−2.65 ± 0.92 vs −2.31 ± 1.03, P < 0.05) compared to the other therapeutic regimens.

Table 1. Characteristics at the start of the TOWER trial of subjects who were enrolled and completed the 1 year follow-up study.

Table 2. Characteristics of the subjects at start of the follow-up study by treatment regimens.

Table 3. Therapeutic regimens in the follow-up study.

Vertebral fractures

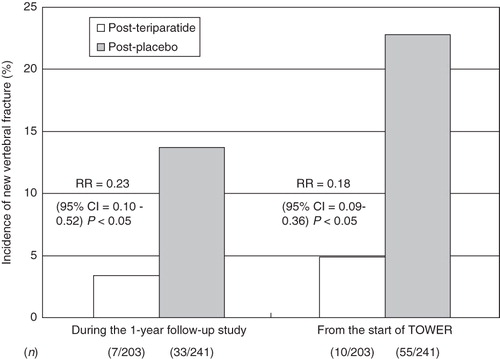

During the 1-year follow-up period, new vertebral fracture occurred in 7/203 (3.4%) subjects in the post-teriparatide group and 33/241 (13.7%) in the post-placebo group (RR: 0.23, 95% CI: 0.10 to 0.52, P < 0.05) (). The cumulative incidences of new vertebral fracture at the end of the follow-up study from the start of the original trial were 4.9% (10/203) in the post-teriparatide group and 22.8% (55/241) in the post-placebo group (RR: 0.18, 95% CI: 0.09 to 0.36, P < 0.05).

Figure 2. Incidences of new vertebral fractures during the 1 year follow-up period (left) and cumulative incidences from the start of the original TOWER trial (right). Open box = post-teriparatide group; gray box = post-placebo group. RR: relative risk; CI: confidence interval.

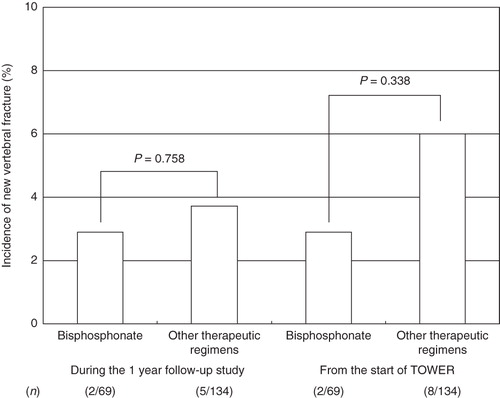

In the post-teriparatide group, the new vertebral fracture incidences during the 1 year follow-up period () were 2.9% (bisphosphonate) and 3.7% (other therapeutics). There was no statistical difference in vertebral fracture incidences between subsequent therapeutic regimens. The incidence values in the post-placebo group subsequently treated with bisphosphonate and other therapeutics were 16.5% and 12.2%, respectively.

Figure 3. Incidences of new vertebral fractures during the 1 year follow-up period (left) and cumulative incidences from the start of the original TOWER trial (right) between subsequent therapeutic regimens in the post-teriparatide group.

In the post-teriparatide group, the cumulative incidences of vertebral fracture for the subjects subsequently treated with bisphosphonate and other therapeutics were 2.9% and 6.0%, respectively (). There was no statistical difference in vertebral fracture incidences between subsequent therapeutic regimens. The cumulative incidence values in the post-placebo group receiving bisphosphonate and the other therapeutic regimens were 28.2% and 19.9%, respectively. The differences in the cumulative incidence values in the post-placebo group were not significant.

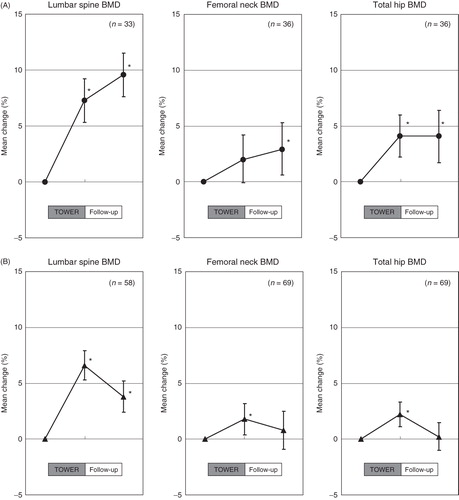

Bone mineral density

In subjects who were subsequently treated with bisphosphonate in the post-teriparatide group, the mean BMD values at the lumbar spine, femoral neck, and total hip from the start of the original trial significantly increased by 9.6%, 2.9%, and 4.1%, respectively, at the end of the follow-up period (P < 0.05) (). During the 1 year follow-up, lumbar spine BMD significantly increased (+2.3%, P < 0.05). Significant BMD increases were not observed in the femoral neck (+0.9%) or total hip (0.0%). The values in the post-placebo group were 3.4%, 0.6%, and 0.1%, respectively. The differences from the start of the original trial were significant at the lumbar spine only (P < 0.05). The differences between subjects in the post-teriparatide and the post-placebo groups were significant at the lumbar spine and total hip (P < 0.05).

Figure 4. Mean percentage change in BMD. The percentage change from the start of the original TOWER trial to the end of the follow-up study in lumbar spine, femoral neck, and total hip with bisphosphonates (A) and other therapeutic regimens (B) in the post-teriparatide group. BMD: bone mineral density. *P < 0.05 versus the value at the start of original trial.

For subjects treated with other therapeutic regimens in the post-teriparatide group, the mean changes in BMD values at the end of the follow-up period were 3.8%, 0.8%, and 0.2% at the lumbar spine, femoral neck, and total hip, respectively (). During the 1 year follow-up, significant BMD decreases were observed at the lumbar spine (−2.8%) and total hip (−2.0%) (P < 0.05). The BMD values for lumbar, femoral neck, and total hip at the end of the follow-up period in the post-placebo group were 0.4%, −3.1%, and −3.2%, respectively. In the post-teriparatide group, a significant increase in BMD from the start of the original trial was found only at the lumbar spine at the end of the follow-up period (P < 0.05). The differences between subjects belonging to the post-teriparatide and post-placebo groups maintained significance at all measured sites (P < 0.05).

Discussion

The reduction in the risk of vertebral fracture was maintained for 1 year after the 72 week treatment with weekly teriparatide injections (56.5 μg) in postmenopausal women and elderly men with severe osteoporosis. In subjects treated with weekly teriparatide, the cumulative incidences of vertebral fracture at 72 weeks + 1 year from the start of the teriparatide treatment were also significantly reduced, regardless of the subsequent treatment of bisphosphonate or other therapeutic regimens. BMD values continued to increase for the lumbar spine and femoral neck in subjects treated with bisphosphonates. However, in subjects treated with other therapeutic regimens, BMD gains at the lumbar, femoral neck, and total hip were not maintained during the follow-up period.

In this follow-up study, the risk of a new vertebral fracture in subjects treated with weekly teriparatide was significantly reduced (by 77%) and the absolute risk reduction was 10.3% compared to subjects treated with placebo. These reductions of relative and absolute risks were similar to the respective values of 80% and 11.4% obtained in the original study (TOWER) after 72 weeksCitation13. Thus, the efficacy of weekly 56.5 μg teriparatide injections in the prevention of new vertebral fractures during the post-treatment period (1 year) seems to be similar to that after the 72 week treatment period. Sustained vertebral fracture risk reduction after withdrawal of daily teriparatide for 18 to 24 months has been observed in postmenopausal women and men with osteoporosis treated with daily teriparatide injections at doses of 20 μg and 40 μgCitation14,Citation15,Citation17. We found that weekly teriparatide injections also had a sustaining effect, reducing vertebral fracture risk for the 1 year post-treatment period. Moreover, 1 year incidences and the cumulative incidences from the start of the original trial maintained a significant reduction in the post-teriparatide group regardless of subsequent therapeutic regimen. Thus, it is anticipated that the sustained efficacy of weekly teriparatide injections on the risk of vertebral fracture may not be greatly affected by subsequent medication for at least 1 year after the withdrawal.

Subsequent bisphosphonate treatment continued to increase BMD at the lumbar spine and femoral neck and maintained at the total hip. The mean percentage increases in BMD during the follow-up period were apparently equivalent between the post-teriparatide and post-placebo groups. These findings are comparable to the BMD responses in postmenopausal women and men with osteoporosis treated with daily teriparatide injectionsCitation14,Citation15,Citation18. Therefore, the use of weekly teriparatide, although reducing bone resorption concomitantly with increasing bone formationCitation13, does not appear to diminish the ability of bone to respond to subsequent bisphosphonate treatment. In the subjects sequentially treated with other therapeutics including raloxifene and activated vitamin D, BMDs at the lumbar spine, femoral neck, and total hip were decreased. This finding is somewhat different from the result given in a study of daily teriparatide injections that reported that other antiresorptive agents such as SERM maintain BMD after discontinuation of daily teriparatideCitation16. After discontinuation of weekly teriparatide, bisphosphonates may show better results for BMD.

Sustained risk reduction of vertebral fracture is apparently related to the continuous increase in BMD in subjects subsequently treated with bisphosphonates. In subjects treated with other therapeutic regimens, vertebral fracture reduction may not be explained solely by BMD gains attained by the preceding teriparatide treatment.

The contribution that increased BMD makes to anti-fracture efficacy remains controversial. There are some reports that BMD changes induced by antiresorptive drugs, such as bisphosphonates or SERMs, were partly predictive of future fracture riskCitation20,Citation21, whereas other studies reported that the correlations were not linearCitation22,Citation23. Cummings et al. reported that the short-term changes in lumbar and femoral BMDs after antiresorptive treatment could not solely be attributed to judgment of the drug efficacy at an individual level because of the presence of ‘regression to the mean’ BMD valueCitation24. Moreover, the percentage change in BMD is affected by the baseline value. In patients with an extremely low baseline BMD, the percentage change would be highly influenced by a small gain or decrease. Therefore, the percentage change in BMD only partially indicates anti-fracture efficacy.

Reportedly, weekly teriparatide administration is associated with increased material properties of bone in ovariectomized monkeysCitation25. Thus, the bone quality improvements by weekly teriparatide injections may contribute to the sustained reduction in the incidence of vertebral fracture for 1 year after cessation. However, BMD gain is one of the major factors for improving bone strength, which is of primary importance in the treatment of osteoporosis. In fact, BMD increased only in subjects with subsequent bisphosphonate treatment, and the incidence of vertebral fracture in subjects with subsequent bisphosphonate treatment was lower compared to the other therapeutic regimens at 1 year follow-up, although this difference was not significant. A significant reduction in vertebral fracture risk might be observed in subjects who undergo subsequent bisphosphonate treatment for a longer period. Therefore, the subsequent use of bisphosphonates seems to be a useful choice after withdrawal of weekly teriparatide injections as a treatment strategy for the long-term care of patients with osteoporosis.

There are limitations in this observational follow-up study. Data on calcium and vitamin D supplementations were not obtained in the follow-up period. Thus, use of these supplements may not be balanced between the post-teriparatide and post-placebo groups during the follow-up period. The regimens of subsequent medication after discontinuation of the original TOWER trial were not randomly allocated, but the rate of each regimen did not indicate statistical difference. Since subsequent medications other than bisphosphonate were variable, we were not able to analyze the efficacy of specific agents.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study demonstrated that vertebral risk reduction was sustained for 1 year after withdrawal of weekly teriparatide treatment. The sustained effect did not seem to be greatly affected by the subsequent therapeutic regimens; however, BMD gains continued with subsequent bisphosphonate treatment. Bisphosphonates seem to be a useful choice as a subsequent treatment to weekly teriparatide in postmenopausal women and men with severe osteoporosis.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This study was supported by the Asahi Kasei Pharma Corporation.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

T.S. received research grants and consulting fees from Asahi Kasei Pharma and Daiichi Sankyo. M.S. received consulting fees from Chugai, Daiichi Sankyo, Asahi Kasei Pharma, Teijin, and MSD. M.I. has received research grants and consulting fees or other remuneration from Chugai, Daiichi Sankyo, JT, and Asahi Kasei Pharma. M.F. has received consulting fees from Astellas and Asahi Kasei Pharma. H.H. received research grants and consulting fees from Asahi Kasei Pharma, Chugai, Astellas, Ezai, Takeda, and MSD. T.N. received research grants and/or consulting fees from Chugai, Teijin, Asahi Kasei Pharma, and Daiichi Sankyo. T.K. is an employee of Asahi Kasei Pharma Corporation. Te.N., H.K. and Te.S. have disclosed that they have no significant relationships with or financial interests in any commercial companies related to this study or article.

References

- Raisz LG. Pathogenesis of osteoporosis: concepts, conflicts, and prospects. J Clin Invest 2005;115:3318-25

- NIH 2001 Consensus Conference. Osteoporosis prevention, diagnosis, and therapy. JAMA 2002;282:785-95

- World Health Organization (WHO). Assessment of fracture risk and its application to screening for postmenopausal osteoporosis: report of a WHO study group. WHO Technical Report Series, Report No. 843. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO, 1994

- European Perspective Osteoporosis Study Group. Incidence of vertebral fracture in Europe: results from the European Prospective Osteoporosis Study (EPOS). J Bone Miner Res 2002;17:716-24

- Van der Klift M, de Laet C, Mcclosky EV, et al. The incidence of vertebral fractures in men and women: the Rotterdam Study. J Bone Miner Res 2002;17:1051-6

- Fujiwara S, Kasagi F, Masunari N, et al. Fracture prediction from bone mineral density in Japanese men and women. J Bone Miner Res 2003;18:1547-53

- Delmas PD, Rizzoli R, Cooper C, et al. Treatment of patients with postmenopausal osteoporosis is worthwhile. The position of the International Osteoporosis Foundation. Osteoporos Int 2005;16:1-5

- Kanis JA, Borgstrom F, de Laet C, et al. Assessment of fracture risk. Osteoporosis Int 2005;16:581-9

- Kurland ES, Cosman F, McMahon DJ, et al. Parathyroid hormone as a therapy for idiopathic osteoporosis in men: effects on bone mineral density and bone markers. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2000;85:3069-76

- Neer RM, Arnaud CD, Zanchetta JR, et al. Effect of parathyroid hormone (1-34) on fractures and bone mineral density in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. N Engl J Med 2001;344:1434-41

- Orwoll E, Scheele WH, Paul S, et al. The effect of teriparatide [human parathyroid hormone (1-34)] therapy on bone mineral density in men with osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Res 2003;18:9-17

- Miyauchi A, Matsumoto T, Sugimoto T, et al. Effects of teriparatide on bone mineral density and biochemical markers in Japanese subjects with osteoporosis at high risk of fracture in a 24-month clinical study: 12-month, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind and 12-month open-label phases. Bone 2010;47:493-502

- Nakamura T, Sugimoto T, Nakano T, et al. Randomized teriparatide [human parathyroid hormone (PTH) 1-34] once-weekly efficacy research (TOWER) trial for examining the reduction in new vertebral fractures in subjects with primary osteoporosis and high fracture risk. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2012;97:3097-106

- Kurland ES, Heller SL, Diamond B, et al. The importance of bisphosphonate therapy in maintaining bone mass in men after therapy with teriparatide [human parathyroid hormone (1-34)]. Osteoporos Int 2004;15:992-7

- Kauman J-M, Orwoll E, Goemaere S, et al. Teriparatide effects on vertebral fractures and bone mineral density in men with osteoporosis: treatment and discontinuation of therapy. Osteoporos Int 2005;16:510-16

- Adami S, San Martin J, Munoz-Torres M, et al. Effect of raloxifene after recombinant teriparatide [hPTH(1-34)] treatment in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int 2008;19:87-94

- Lindsay R, Scheele WH, Neer R, et al. Sustained vertebral fracture risk reduction after withdrawal of teriparatide in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. Arch Intern Med 2004;164:2024-30

- Prince R, Sipos A, Hossain A, et al. Sustained nonvertebral fragility fracture risk reduction after discontinuation of teriparatide treatment. J Bone Miner Res 2005;20:1407-513

- Genant HK, Jergas M, Palermo L, et al. Comparison of semiquantitative visual and quantitative morphometric assessment of prevalent and incident vertebral fracture. J Bone Miner Res 1996;11:984-96

- Wasnich RD, Miller PD. Antifracture efficacy of antiresorptive agents are related to changes in bone density. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2000;85:231-6

- Hochberg MC, Ross PD, Black D, et al. Larger increases in bone mineral density during alendronate therapy are associated with a lower risk of new vertebral fractures in women with postmenopausal osteoporosis. Fracture Intervention Trial Research Group. Arthritis Rheum 1999;42:1246-54

- Delmas PD, Seeman E. Changes in bone mineral density explain little of the reduction in vertebral or nonvertebral fracture risk with anti-resorptive therapy. Bone 2004;34:599-604

- Watts NB, Geusens P, Barton IP, et al. Relationship between changes in BMD and nonvertebral fracture incidence associated with risedronate: reduction in risk of nonvertebral fracture is not related to change in BMD. J Bone Miner Res 2005;20:2097-104

- Cummings SR, Palermo L, Browner W, et al. Monitoring osteoporosis therapy with bone densitometry: misleading changes and regression to the mean. Fracture Intervention Trial Research Group. JAMA 2000;283:1318-21

- Saito M, Marumo K, Kida Y, et al. Changes in the contents of enzymatic immature, mature, and non-enzymatic senescent cross-links of collagen after once-weekly treatment with human parathyroid hormone (1-34) for 18 months contribute to improvement of bone strength in ovariectomized monkeys. Osteoporos Int 2010;22:2373-83