Abstract

Objective:

To evaluate the safety of the fixed combination of ibuprofen and famotidine compared with ibuprofen alone from two 24-week, multicenter, double-blind trials designed to evaluate the comparative incidence of endoscopically documented upper gastrointestinal ulcers and a 28-week double-blind extension study.

Research design and methods:

Safety was analyzed by pooling data from the two double-blind trials and the follow-on study. Safety was assessed by monitoring the incidence, causality, and severity of adverse events (AEs).

Results:

In the pivotal efficacy and safety trials, discontinuation rates due to any cause and dyspepsia were significantly lower for the ibuprofen/famotidine combination versus ibuprofen alone. Other than dyspepsia, gastrointestinal and cardiovascular AEs of special interest were similar. Events judged to be treatment related were significantly lower with the ibuprofen/famotidine combination (20.6% vs. 25%). In the safety extension population, there were no differences in the discontinuation rates and the reporting of AEs or serious AEs (SAEs) between the two groups. Gastrointestinal-related events were similar between the groups. Incidence of cardiovascular-related AEs of special interest were 11% (ibuprofen/famotidine) and 2% (ibuprofen) (p = 0.06), possibly due to a higher number of rheumatoid arthritis patients in the combination group. Of these, 80% were reports of hypertension (8% ibuprofen/famotidine vs. 2% ibuprofen). Three cases of hypertension in the ibuprofen/famotidine group were considered treatment related. The probability of a cardiovascular event decreased during days 112–167 of treatment and remained low with continued treatment.

Conclusions:

One-year safety data from two pivotal trials and a long-term extension study indicate that the ibuprofen/famotidine combination demonstrates a favorable gastrointestinal safety profile and more patients continued on therapy compared to ibuprofen alone. No new safety signals have been identified. These data offer additional evidence supporting a new therapeutic option to improve gastrointestinal safety and adherence for patients who require long-term ibuprofen.

Introduction

Ibuprofen is the most commonly used non-aspirin nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) in the USCitation1. Ibuprofen has dose-related potency for the management of pain and inflammation and is indicated for a wide range of chronic arthritic and nonarthritic conditionsCitation2,Citation3. Like other NSAIDs, ibuprofen can induce upper gastrointestinal (UGI) ulceration and its complications (gastrointestinal [GI] bleeding, perforation, or obstruction), particularly at higher dosesCitation4–6.

Selective cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors (coxibs) were developed to produce a subclass of NSAIDs with an improved GI safety profileCitation7. However, several placebo-controlled trials of coxibs demonstrated an increased risk of atherothrombotic vascular eventsCitation8,Citation9, which led the US Food and Drug Administration (US FDA) to request a change in all NSAID labeling in 2005Citation10,Citation11.

In February 2014, a joint meeting of the US FDA Arthritis and Drug Safety and Risk Management advisory committees reviewed recent meta-analyses by the Coxib and Traditional NSAID Trialists’ collaborationCitation4,Citation7 to determine whether a distinction could be made within the class of NSAIDs with respect to CV riskCitation12. The meta-analyses from 280 clinical trials of NSAIDs versus placebo demonstrated that coxibs and diclofenac were associated with small but serious vascular risksCitation4. In addition, ibuprofen was associated with major coronary but not vascular events. Of note, naproxen also did not significantly increase major vascular events. The advisory committee members voted 16 to 9 against a change in labeling for specific NSAIDs, suggesting that further evidence on the safety of NSAIDs may be warrantedCitation7.

Famotidine, through inhibition of histamine 2 (H2) receptors, prevents NSAID-induced UGI ulceration by reducing gastric acid secretionCitation13–16 and has a longer duration of action than other H2-receptor antagonists (H2RAs)Citation15,Citation17. Moreover, famotidine may be a practical alternative to proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) in some patients because it is more ideally paired with shorter half-life NSAIDs, such as ibuprofen, from a pharmacokinetic and patient adherence perspectiveCitation18. Famotidine at 80 mg/day, particularly when administered three times a day (TID), maintains gastric pH above important thresholds for both GI healing and prophylaxisCitation18. Clinical studies, including randomized controlled trials, have demonstrated that the use of famotidine at a total daily dose of 80 mg during treatment with NSAIDs reduces the risk of endoscopic UGI ulceration and is generally well toleratedCitation19,Citation20, offering an alternative to PPIs in appropriate at-risk patients.

Long-term use of some PPIs has been associated with complications including increased fracture risk, Clostridium difficile infection and colonization, and hypomagnesemiaCitation21. Evidence from the literature demonstrates that double doses of H2RAs produce significant relative risk (RR) reductions in gastric and duodenal ulcers (RR = 0.44, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.26–0.74 and RR = 0.26, 95% CI 0.11–0.65, respectively), and are as efficacious as PPIs for the prophylaxis of GI damage from NSAIDs, and are better tolerated than misoprostolCitation13,Citation22. Given recent data that raise questions regarding the risk of drug interactions between PPIs and clopidogrelCitation23–26, some clinicians have advocated the use of H2RAs in patients who require chronic use of both NSAIDs and clopidogrelCitation24,Citation25.

Ibuprofen and famotidine do not appear to have either overlapping or synergistic toxicities, and there are neither data nor theoretical concerns suggesting that co-administration of these drugs would result in increased toxicity compared with administration of either drug aloneCitation14,Citation27. Therefore, combining these two drugs into a single tablet is a rational combination that may enhance patient adherence by reducing the number of pills requiredCitation28.

The fixed combination of ibuprofen 800 mg and famotidine 26.6 mg was approved for oral administration in the US in 2011 to treat rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis (OA) and to decrease the risk of developing UGI ulcersCitation29. Given the recent findings and discussions of NSAID safety, analyses of the safety of combination therapy aimed at reducing GI damage from NSAIDs are of particular interest. We report here the pooled safety results from the REDUCE (Registration Endoscopic Studies to Determine Ulcer Formation of HZT-501 Compared with Ibuprofen Efficacy) trialsCitation30,Citation31 and a long-term safety analysis of the fixed combination of ibuprofen and famotidine and ibuprofen alone from a 28-week double-blind extension study.

Patients and methods

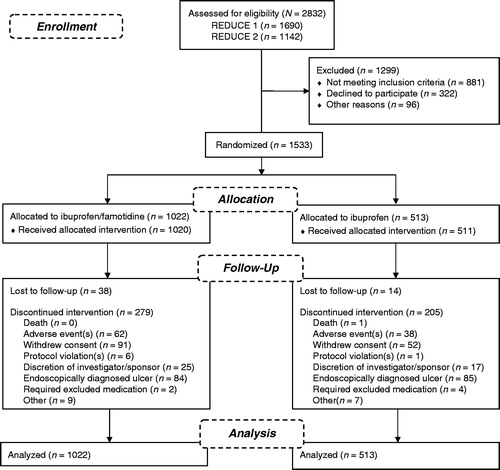

Summaries of the patients and studies included in this safety analysis are outlined in . The pooled safety analysis of the REDUCE-1 (NCT00450658) and REDUCE-2 (NCT00450216) studies was assessed by monitoring adverse events (AEs), changes in clinical laboratory values, changes in vital signs, and changes in physical examination findings over the 24-week treatment period as well as during the 4-week follow-up period (termination visit).

Table 1. Summary of safety studies.

Endoscopies were performed at baseline and weeks 8, 16, and 24 during the treatment period. Endoscopies were not required on the termination visit (week 28). These studies included male and female patients between 40 and 80 years of age (inclusive) who required long-term daily NSAID therapy. Patients could not have used an NSAID within the 30 days prior to study entry but were expected to require daily administration of an NSAID for at least the coming 6 months for conditions such as OA, rheumatoid arthritis, chronic low back pain, chronic regional pain syndrome, and chronic soft tissue pain. Patients could not have a history of erosive esophagitis or of NSAID-associated serious GI complications, a creatinine clearance <45 mL/min, or the presence of five or more erosions observed on endoscopy at screening. Patient demographics and disposition for these studies have been previously reportedCitation30,Citation31.

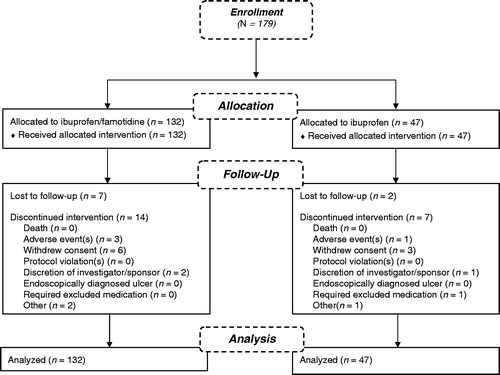

The long-term safety of ibuprofen/famotidine versus ibuprofen was analyzed in a phase 3, multicenter (US), double-blind, parallel-group, 28-week extension study (NCT00613106) (). Patients who participated in the REDUCE studies had the option, at study completion, to continue their assigned treatment. Male and female patients from 40 to 80 years of age were enrolled within 1 week of completing one of the 24-week double-blind REDUCE studies.

Patients were excluded for failing to meet any of the inclusion criteria for REDUCE-1 or REDUCE-2Citation30,Citation31, becoming pregnant, or having a history of any of the following pathologies: malignant disease of the GI tract, erosive esophagitis, clinically significant impairment of kidney or liver function, acute myocardial infarction, unstable cardiac arrhythmias, stroke, uncontrolled hypertension or congestive heart failure, coronary artery bypass graft surgery, and/or uncontrolled diabetes mellitus. Patients were prohibited from taking any NSAIDs other than the study drug during the additional 28-week consecutive treatment period; patients taking low-dose aspirin and/or other anticoagulant medication (which refers to the use of both anticoagulant and antithrombotic medications) could continue to use these medications on their prescribed regimen during the study. Patients were prohibited from taking any interventions that neutralize gastric acid for more than 3 days during any 2-week period, or H2RAs and/or any PPIs other than the study drug during the treatment period.

All studies reported here were conducted in accordance with Clinical Practice guidelines of the International Conference on Harmonization, Title 21 Part 56 of the US Code of Federal Regulations regarding institutional review boards, and the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (amended October 2000). All patients provided informed written consent to participate in the study.

Patients were randomized to the REDUCE-1 and REDUCE-2 trials in a 2:1 ratio to treatment with either fixed-combination ibuprofen/famotidine or ibuprofen alone. Randomization was stratified based on the following two risk factors for ulcer development: (1) concomitant use of low-dose aspirin and/or other anticoagulant medication; (2) history of a UGI (i.e., gastric and/or duodenal) ulcer. Patients continued to receive treatment with the same double-blind study drug (either ibuprofen 800 mg/famotidine 26.6 mg or ibuprofen 800 mg, administered TID) they received while participating in REDUCE-1 or REDUCE-2; crossover between the two treatments was not allowed. Owing to the entry criteria, the 2:1 randomization was lost during the extension study but the blind was maintained, resulting in a 3:1 ratio of patients in the combination tablet group versus those in the ibuprofen treatment group.

Study medication was self-administered orally, without regard to food or liquid consumption, on a double-blind basis, for up to 28 consecutive weeks. Patients visited the study center on day 0 (i.e., on the same day as, or within 1 week after, the week-24 termination visit for REDUCE-1 or REDUCE-2) and at week 14 and week 28 (termination visit). Telephone interviews were conducted at weeks 4, 21, and 32 (a follow-up visit, performed 4 weeks after administration of the last dose of study drug). Patient adherence to the dosing regimen was determined by study personnel by counting the number of tablets remaining in each bottle at the end of the study period.

AEs were collected from all patients beginning at the time of administration of the first dose of the study drug and continued through completion of the 4-week follow-up period. Blood samples were collected on day 0 and at week 14 and 28 (termination visit) for serum chemistry and hematology evaluation. Urine samples were collected on day 0 and at week 28 (termination visit) for standard urinalysis evaluation. Endoscopic examinations were performed only if clinically indicated, per the investigator’s judgment, outside of the planned visits. CV safety was monitored on a quarterly basis by an Independent Data Monitoring Committee.

Due to the black-box warning regarding CV events for NSAIDs contained within the product label, the incidence of events classified under the cardiac disorders system organ class (SOC) and the preferred terms hypertension, accelerated hypertension, prehypertension, increased blood pressure, and heart rate irregular were considered events of special interest that were examined further. From a GI perspective, dyspepsia-related AEs (e.g., abdominal pain, abdominal discomfort, abdominal pain upper, abdominal tenderness, dyspepsia, epigastric discomfort, gastritis, stomach discomfort) were further examined with and without inclusion of nausea. All AEs reported in the safety population were considered treatment emergent (TEAE), that is, they began on or after day 0 and prior to the end of the study period.

Statistical analysis

The safety population was defined as all patients receiving at least one dose of study medication during REDUCE-1, REDUCE-2, or the extension study. Continuous data were summarized with the following descriptive statistics: number of observations, mean, standard deviation (SD), median, minimum, and maximum. Categorical data were summarized with frequencies and percentages. All reported p values are two-sided with 95% CIs. SAS Version 9.1.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) was used for all statistical analyses. Trends in differences between treatments were identified if the p value was >0.05 but <0.20.

Data summaries were presented by actual treatment received (actual treatment and the randomized treatment were the same for all patients). Safety analyses used a Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel test, stratified by randomization strata (i.e., concomitant use of low-dose aspirin and/or other anticoagulant medication and history of a UGI), to compare treatment-emergent AE (TEAE) incidence between treatment groups for AEs occurring in >5% of patients in either treatment group. A chi-square test was used to compare the proportion of patients in the two treatment groups who terminated early from the study. All AEs were coded using the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities, Version 9.1 (MedDRA, McLean, VA, USA).

Results

Primary safety study population

Disposition, demographics, and exposure

The primary safety population for REDUCE-1 and REDUCE-2 included the pooled data from the two pivotal studies, resulting in an overall safety population of 1533 subjects, of which 1022 patients received the combination and 511 patients received 800 mg ibuprofen (). There was a statistically significant greater number of patients in the ibuprofen/famotidine group (69%) that completed the study when compared to the ibuprofen group (57.1%; p < 0.0001) (). Overall discontinuations of therapy were significantly different favoring ibuprofen/famotidine (31%) versus ibuprofen (42.9%) (p < 0.0001, and ). Significantly more patients in the ibuprofen group (n = 85, 16.6%) discontinued early compared to the ibuprofen/famotidine group (n = 84, 8.2%) due to an endoscopically diagnosed UGI ulcer (p < 0.0001, ).

Table 2. Overview of select combined safety events in the REDUCE-1 and REDUCE-2 trials.

Table 3. Patient demographics and baseline characteristics for the safety extension population.

The occurrence of an AE was also a major reason for early discontinuation, with 62 (6.1%) of the ibuprofen/famotidine and 38 (7.4%) of the ibuprofen patients discontinuing for this reason (). Significantly higher numbers of patients treated with ibuprofen alone compared to the ibuprofen/famotidine combination terminated the trial due to dyspepsia (p = 0.014). Overall, in the primary safety population, the mean (±SD) number of days patients were exposed to the ibuprofen/famotidine combination was 139.1 ± 51.57 compared to 125.8 ± 56.31 in the comparator group, reflecting the higher number of patients who terminated from the study early in the ibuprofen group; these terminations were primarily due to the development of UGI ulcers owing to ibuprofen exposure (p = 0.02). The median daily dosages of ibuprofen were comparable in both treatment groups (ibuprofen/famotidine, 2281 mg vs. ibuprofen, 2264 mg).

AEs

At least one TEAE was reported by 56.2% (862/1533) of the primary safety population, with 55.0% (562/1022) and 58.7% (300/511) of patients in the ibuprofen/famotidine combination and ibuprofen groups, respectively (p = 0.16, ).

In evaluating TEAEs with greater than 1% incidence, no statistically significant differences were found between the ibuprofen/famotidine combination and ibuprofen groups, with the exception of dyspepsia, which was reported by 4.7% (48/1022) of the ibuprofen/famotidine group and 8.0% (41/511) of the ibuprofen group (p = 0.0086), demonstrating the known efficacy of the daily dose of famotidine (80 mg) within the combinationCitation18,Citation32. The comparison of TEAEs occurring in the renal and urinary disorders categories yielded a p value of 0.0631 favoring the ibuprofen/famotidine combination. Special interest vascular and cardiac disorder TEAEs were low and not significantly different between treatment groups, ≤3.7% and ≤1%, respectively. Likewise, laboratory findings for TEAEs associated with increased creatinine and transaminases from baseline were low with the ibuprofen/famotidine combination; 0.9% (9/1022) and 0.3% (3/1022), respectively.

SAEs

Overall, 3.2% (33/1022) of patients in the ibuprofen/famotidine group and 3.3% (17/511) of patients in the ibuprofen group reported a SAE. The highest numbers of reported SAEs were in the infections and infestations category, consisting of 0.6% (6/1022) of patients in the ibuprofen/famotidine group and 0.6% (3/511) of patients in the ibuprofen group.

In the SAEs of special interest, four ibuprofen/famotidine patients reported the GI disorder SAEs of abdominal hernia, hemorrhoidal hemorrhage, hemorrhoids, inguinal hernia, and esophageal ulcer. All of these were considered not related to the study drug, with the exception of the esophageal ulcer that the trials were conducted to monitor. In the renal and urinary disorders category, three ibuprofen/famotidine patients reported acute renal failure (all considered possibly related to study drug) and one patient reported calculus ureteric (considered probably not related to study drug).

In the cardiac and vascular disorders category, chest pain was reported by 0.3% (3/1022) of patients in the ibuprofen/famotidine combination group and 0.2% (1/511) of patients in the ibuprofen group. Three coronary artery disease SAEs were reported by two ibuprofen patients and cardio-respiratory arrest was reported by one patient, all of which were considered probably not related to study drug. One SAE of hypertension with the ibuprofen/famotidine combination was reported and not considered to be related to study drug.

There was a single death reported in the primary safety population which occurred in the ibuprofen cohort; the patient died as a result of cardio-respiratory arrest and multi-organ failure attributed by the investigator to acetaminophen (paracetamol) toxicity.

Summary of AEs ascribed to therapy

Overall, 20.6% (211/1022) of patients in the ibuprofen/famotidine treatment group and 25.0% (128/511) of the ibuprofen group (p = 0.0502) reported events considered related to treatment, with most occurring in the GI disorders category. A significantly higher number of possibly related GI TEAEs were reported in the ibuprofen group, with 20.0% (102/511) compared to 14.8% (151/1022) of patients in the ibuprofen/famotidine combination group (p < 0.01). Likewise, gastroesophageal reflux TEAEs tended to be reported by more patients treated with ibuprofen alone than the ibuprofen/famotidine combination (2.5% vs. 1.2%, respectively, p = 0.14).

Vascular disorder TEAEs that were considered possibly drug related were low and not different between the ibuprofen/famotidine combination and ibuprofen alone (1.2 % vs. 1.6% respectively, p = 0.52). The numbers of hypertension TEAEs thought to be possibly related were also low and not significantly different between the groups (3.1% ibuprofen/famotidine and 2.2% with ibuprofen alone, p = 0.31). Finally, there were no cardiac disorder TEAEs reported that were thought to be drug related in either group.

Safety extension population

Disposition, demographics and exposure

The safety extension population included all patients who received at least one dose of study drug during the extension period. Of the 179 patients who entered the double-blind extension study, 132 received the ibuprofen/famotidine combination tablet and 47 received ibuprofen alone (). Patients were well matched between treatment groups with no statistically significant differences for any demographic variables () and similar to the double-blind populationCitation30,Citation31.

Exposure

The median daily ibuprofen dose was similar for both groups (2362 mg for the combination tablet vs. 2368 mg for ibuprofen) (). Total exposure to medication of ≥24 weeks occurred in 81% of the combination-tablet-treated patients compared with 77% for ibuprofen-treated patients. There were no appreciable differences in drug exposure by gender, age group, or indication between the treatment groups.

Table 4. Exposure to study medication in the safety and safety extension populations.

AEs

In the ibuprofen/famotidine combination group 42% (n = 55) of patients experienced AEs compared with 34% (n = 16) of patients in the ibuprofen group (p = 0.4) (). Overall, 40% (n = 71) of patients experienced at least one AE during the study period. No statistically significant differences were found regarding the frequency of AEs between the ibuprofen/famotidine combination and ibuprofen groups, with the exception of rib fracture, laryngitis, and lower respiratory tract infection, which were reported by no patients in the ibuprofen/famotidine group and 4.3% (2 of 47) of patients in the ibuprofen group (p = 0.0206 for rib fracture, p = 0.0163 for laryngitis and lower respiratory tract infection). The infections and infestations SOC had the highest overall incidence of AEs (17%, ). Of these AEs, the most common were viral gastroenteritis, influenza, and sinusitis. Additionally, no significant difference in AEs occurred on the basis of gender or age.

Table 5. AEs occurring in ≥1% of the extension safety population.

SAEs

No deaths occurred during the study. The majority of the AEs were of mild to moderate intensity, with no life-threatening AEs reported during the study (). The incidence of SAEs was 3% in the ibuprofen/famotidine group and 4.3% in the ibuprofen group. The incidence of SAEs leading to discontinuation was similar between the two treatment groups. Similarly, the incidence of overall AEs leading to discontinuation was similar in the two treatment groups (ibuprofen/famotidine, 1.5%; ibuprofen, 2.1%) (). Changes from baseline in clinical laboratory parameters were generally small, comparable between the two treatment groups, and consistent with AEs listed in the prescribing information for ibuprofen and/or famotidine. No clinically meaningful differences in vital sign measurements, physical examination findings, or other observations related to safety were observed between the two treatment groups.

Table 6. Serious AEs in the safety extension population.

Table 7. AEs leading to discontinuation in the safety extension population.

GI and CV events of special interest

The overall incidence of CV-related AEs of special interest was 8% (15/179 patients), with no statistically significant difference observed between the ibuprofen/famotidine group and ibuprofen group (11% vs. 2%; p = 0.06) (). Of the reported CV-related events, 80% were reports of hypertension, a known effect of NSAIDsCitation27. Hypertension was reported by 8% of patients who received the combination product and 2% of patients who received ibuprofen (p = 0.1275). Blood pressure increase was the only other CV-related AE that was reported by two or more patients in any treatment group. The probability of a CV event decreased during days 112 to 167 of treatment and remained low with continued treatment ().

Table 8. Incidence of AEs of special interest in the safety extension population.

Table 9. Cumulative incidence of treatment-emergent adverse events of special interest by exposure time.

The overall incidence of dyspepsia-related AEs in the safety extension population was 16% (28/179 patients) including nausea and 14% (25/179 patients) excluding nausea (). There were no statistically significant differences between the overall incidence of dyspepsia-related AEs between the two groups with (p = 0.5) or without nausea (p = 0.5). The most commonly reported GI-related AE of special interest was dyspepsia (p = 0.3).

Summary of AEs ascribed to therapy

Overall, 20.7% (37/179) of patients reported events considered to be possibly related to treatment, 19.7% (26/132) of patients in the ibuprofen/famotidine group and 23.4% (11/47) of the ibuprofen group (p = 0.59). The most common of which were GI disorders, reported by 13.4% (24/179) of the study population. A higher proportion of possibly related GI AEs were reported by the ibuprofen group (p = 0.40). These included dyspepsia (3.8% vs. 2.1%), abdominal distension (1.5% vs. 0.0%), stomach discomfort (1.5% vs. 0.0%), and vomiting (0.8% vs. 0.0%), in the ibuprofen/famotidine and ibuprofen groups, respectively. The incidence of hypertension was low, with 12/179 subjects (6.7%) reporting hypertension, 3 of whom (1.7%, 3/179 subjects) were considered related to therapy, all in the ibuprofen/famotidine group (p = 0.08).

Discussion

Ibuprofen 800 mg and 26.6 mg famotidine given TID together in a combination tablet have previously been shown to reduce the risk for upper GI ulcers by approximately 50% in a general musculoskeletal pain population as well as an OA population specificallyCitation30,Citation31,Citation33. Up to 1 year of dosing with the combination product was completed by patients in the phase 3, US multicenter, double-blind studies and the extension study. These studies, and others with a naproxen/esomeprazole combination, indicate that the relative decrease in endoscopic damage is similar to that found with celecoxib (relative risk reduction of 40% to 50%)Citation30,Citation31,Citation34,Citation35.

Over the 1-year analysis, the incidence of AEs, AEs leading to discontinuation, and SAEs were similar between the ibuprofen/famotidine and the ibuprofen group with TEAEs reported more frequently among the ibuprofen group. AEs leading to discontinuation were similar between the two treatment groups in aggregate, with data from the REDUCE trials favoring the ibuprofen/famotidine combination.

The drop-out rates reported here with the ibuprofen/famotidine combination (approximately 30%) and ibuprofen alone (approximately 43%) were slightly higher than the drop-out rates reported in similar GI risk reduction studies with naproxen. Goldstein and colleaguesCitation34 enrolled subjects in two randomized, double-blind, parallel-group, controlled, multicenter studies comparing a fixed combination of 20 mg omeprazole and 500 mg naproxen to 500 mg naproxen alone for 6 months. In these two naproxen studies, the reported premature discontinuation rate was 6.9% and 10.5% for the combination therapy group and 15.7% and 18.1% for the naproxen only group, respectively. Collectively, these data indicate that the improvement in discontinuation rates from the two fixed-dose gastroprotective combinations compared to the NSAIDs alone are generally comparable (13% vs. 8%). The discontinuation rates and ulcer risk, compared to the NSAID alone, were significantly reduced in all of these studies indicating both agents are effective gastroprotective approachesCitation30,Citation34.

The need to balance NSAID-associated CV- and GI-event risk with efficacy has long been recognized by physicians, industry, and government institutionsCitation4,Citation33,Citation36,Citation37. In the present studies, no serious GI or CV complications were reported with the ibuprofen/famotidine combination and overall CV events were low (1% in the REDUCE studies and 8% in the extension study). Further, there were no significant differences noted in CV AEs with ibuprofen, though a trend appeared to exist in the extension study with a slightly higher non-serious CV event rate with the ibuprofen/famotidine combination. The most commonly occurring CV-related event was hypertension, which accounted for 80% of 14 CV-related events reported. The number of events was small: 11 with the ibuprofen/famotidine combination vs. one with ibuprofen alone) and only three of them were considered treatment related. One potential explanation for the slightly higher rate of hypertension TEAEs with the combination is that the ibuprofen/famotidine combination group in the extension study trended toward higher numbers (7.57%, 10/132) of rheumatoid arthritis patients compared with the ibuprofen alone group (0%, 0/47, p = 0.053). It is well documented that the presence of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) increases CV risk, including hyptertensionCitation38, but NSAIDs do not further increase that riskCitation39. In the double-blind REDUCE studies, the percentages of RA patients were comparable and no trends towards higher rates of hypertension were seen in those analyses (3% ibuprofen/famotidine vs. 2% with ibuprofen alone).

Moreover, based on the review of the safety data, no CV signals were reported in either pivotal study. There was no reason to suspect a difference in CV-related events between study groups because the mean doses and the overall exposure of ibuprofen were the same between treatment groups and famotidine is not known to substantially increase CV riskCitation32,Citation40. Furthermore, no significant differences in safety events were observed between men and women. These data are supported by findings from the Women’s Health Initiative, which reported an increased risk of CV events in women taking coxibs and naproxen, but not ibuprofenCitation36.

There are potential limitations to these analyses. The higher numbers of patients taking ibuprofen/famotidine compared to ibuprofen (3:1 ratio), the small numbers of patients, and the lack of randomization in the extension study could potentially lead to a channeling or survival bias. For example, in evaluating AEs with a greater than 1% incidence in the REDUCE trials no significant differences were reported between treatment groups except dyspepsia which was significantly lower (47%) with the ibuprofen/famotidine combination as compared to ibuprofen alone. This difference was not carried over into the extension study likely because patients who had endoscopically diagnosed ulcers were excluded in the safety extension population and those who tolerated ibuprofen well were more likely to finish the long-term follow-up (survival bias). Due to the nature of the REDUCE study population, which predominantly included patients younger than 65 years of age without a prior history of GI ulcer, results may not be generalizable to the entire population. Finally, the extension study was small and may potentially suffer from survivor treatment selection bias.

Conclusions

Overall, the 1-year safety profile of the ibuprofen/famotidine combination indicates improved persistence over ibuprofen alone. AEs were generally similar between the groups, with the exception of dyspepsia, which was reduced by the ibuprofen/famotidine combination in the pooled analysis. CV events were low and not significantly different between treatment groups. Coupled with the previously reported findings of a significant decrease in UGI ulcer risk with the fixed combination of ibuprofen/famotidine versus ibuprofen alone, these data offer evidence supporting an additional therapeutic option for patients who require long-term ibuprofen therapy.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

The design, study conduct, and financial support for this study were provided by Horizon Pharma, Inc. Horizon participated in the interpretation of data, review, and approval of the manuscript.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

J.D.K., A.Y.G., and J.B. have disclosed that they are employees of Horizon Pharma, Inc. A.E.B. and R.J.H. have disclosed that they have been consultants for Horizon Pharma, Inc. A.E.B. has also been a speaker for AbbVie, Questcor, and UCB.

CMRO peer reviewers on this manuscript have received an honorarium from CMRO for their review work, but have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Tonya Goodman and Cathryn M. Carter MS of Arbor Communications Inc., Ann Arbor, MI, USA for medical writing support; this support was funded by Horizon Pharma Inc.

Previous presentations: Goldstein JL, Lakhanpal S, Cohen SB, et al. Long term safety of an NSAID with built-in gastroprotection for treatment of pain and inflammation related to OA and RA: comparative results from blinded and open label one year safety trials of a single-tablet combination of ibuprofen-famotidine [abstract no. Mo1215]. Gastroenterology 2011;140(5 Suppl 1):S585; and Weinblatt ME, Genovese MC, Kivitz AJ, et al. Efficacy, safety and tolerability of HZT-501, including users of low-dose aspirin, a single-tablet combination of ibuprofen–famotidine: results of two phase 3 trials [abstract no. 945]. Arthritis Rheum 2010;62(10 Suppl):S391-2.

References

- Paulose-Ram R, Hirsch R, Dillon C, et al. Prescription and non-prescription analgesic use among the US adult population: results from the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III). Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2003;12:315-26

- Derry C, Derry S, Moore RA, McQuay HJ. Single dose oral ibuprofen for acute postoperative pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009;3:CD001548

- Lee P, Anderson JA, Miller J, et al. Evaluation of analgesic action and efficacy of antirheumatic drugs. Study of 10 drugs in 684 patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 1976;3:283-94

- Coxib and traditional NSAID Trialists’ (CNT) Collaboration, Bhala N, Emberson J, et al. Vascular and upper gastrointestinal effects of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: meta-analyses of individual patient data from randomized trials. Lancet 2013;382:769-79

- Laine L. GI risk and risk factors of NSAIDs. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 2006;47(Suppl 1):S60-6

- Larkai EN, Smith JL, Lidsky MD, Graham DY. Gastroduodenal mucosa and dyspeptic symptoms in arthritic patients during chronic nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use. Am J Gastroenterol 1987;82:1153-8

- Bello AE, Kent JD, Grahn AY, et al. Risk of upper gastrointestinal ulcers in patients with osteoarthritis receiving single-tablet ibuprofen/famotidine versus ibuprofen alone: pooled efficacy and safety analyses of two randomized, double-blind, comparison trials. Postgrad Med 2014;126:82-91

- Bresalier RS, Sandler RS, Quan H, et al. Cardiovascular events associated with rofecoxib in a colorectal adenoma chemoprevention trial. New Engl J Med 2005;52:1092-102

- Solomon SD, McMurray JJ, Pfeffer MA, et al. Cardiovascular risk associated with celecoxib in a clinical trial for colorectal adenoma prevention. New Engl J Med 2005;352:1071-80

- COX-2 selective (includes Bextra, Celebrex, and Vioxx) and non-selective non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). FDA Postmarket Drug Safety Information for Patients and Providers. Washington, DC: FDA, 7 April 2005. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/drugs/drugsafety/postmarketdrugsafetyinformationforpatientsandproviders/ucm103420.htm [Last accessed 21 October 2014]

- Salvo F, Antoniazzi S, Duong M, et al. Cardiovascular events associated with the long-term use of NSAIDs: a review of randomized controlled trials and observational studies. Expert Opin Drug Saf 2014;13:573-85

- February 10–11, 2014: Joint meeting of the Arthritis Advisory Committee and Drug Safety and Risk Management Advisory Committee meeting announcement. FDA Advisory Committee Calendar. Washington, DC: FDA, 8 January 2014. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/AdvisoryCommittees/Calendar/ucm380871.htm [Last accessed 21 October 2014]

- Rostom A, Dube C, Wells G, et al. Prevention of NSAID-induced gastroduodenal ulcers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2002;(Issue 4):CD002296

- Merck Sharpe & Dohme. Pepcid prescribing information. West Point, PA, USA: Merck Sharpe & Dohme, 1986

- Smith JL, Gamal MA, Chremos MA, Graham DY. Famotidine, a new H2-receptor antagonist. Effect on parietal, nonparietal, and pepsin secretion in man. Dig Dis Sci 1985;30:308-12

- Takeda T, Yamashita Y, Mitsui Y, Shimazaki S. Histamine decrease the permeability of an endothelial cell monolayer to dextran: preliminary report. J Japan Surgical Assoc 1992;93:1513

- Schunack W. Pharmacology of H2-receptor antagonists: an overview. J Int Med Res 1989;17(Suppl 1):9-16A

- Kent JD, Holt RJ, Jong D, et al. Pharmacodynamic evaluation of intragastric pH and implications for famotidine dosing in the prophylaxis of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug induced gastropathy – a proof of concept analysis. J Drug Assess 2014;3:20-7

- Hudson N, Taha AS, Russell RI, et al. Famotidine for healing and maintenance in nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug-associated gastroduodenal ulceration. Gastroenterology 1997;112:1817-22

- Taha AS, Hudson N, Hawkey CJ, et al. Famotidine for the prevention of gastric and duodenal ulcers caused by nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. N Engl J Med 1996;334:1435-9

- Corleto VS, Festa S, Di Giulio E, Annibale B. Proton pump therapy and potential long-term harm. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes 2014;32:3-8

- Moore A, Makinson G, Li C. Patient-level pooled analysis of adjudicated gastrointestinal outcomes in celecoxib clinical trials: meta-analysis of 51,000 patients enrolled in 52 randomized trials. Arthritis Res Ther 2013;15:R6

- Updated safety information about a drug interaction between clopidogrel bisulfate (marketed as Plavix) and omeprazole (marketed as Prilosec and Prilosec OTC). FDA Public Health Advisory. Washington, DC: FDA/Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, 17 November 2009. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrugSafetyInformationforPatientsandProviders/DrugSafetyInformationforHeathcareProfessionals/PublicHealthAdvisories/ucm190825.htm [Last accessed 2 April 2014]

- Ho PM, Maddox TM, Wang L, et al. Risk of adverse outcomes associated with concomitant use of clopidogrel and proton pump inhibitors following acute coronary syndrome. JAMA 2009;301:937-44

- Khalique SC, Cheng-Lai A. Drug interaction between clopidogrel and proton pump inhibitors. Cardiol Rev 2009;17:198-200

- Targownik LE, Metge CJ, Leung S, Chateau DG. The relative efficacies of gastroprotective strategies in chronic users of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Gastroenterology 2008;134:937-44

- Pfizer. Motrin prescribing information. New York, NY, USA: Pfizer Inc., 2007

- Bangalore S, Kamalakkannan G, Parkar S, Messerli FH. Fixed-dose combinations improve medication compliance: a meta-analysis. Am J Med 2007;120:713-19

- Horizon. Duexis prescribing information. Deerfield, IL, USA: Horizon Pharma USA Inc., 2012

- Laine L, Kivitz AJ, Bello AE, et al., on behalf of the REDUCE-1 and -2 Study Investigators. Double-blind randomized trials of single-tablet ibuprofen/high-dose famotidine vs ibuprofen alone for reduction of gastric and duodenal ulcers. Am J Gastroenterol 2012;107:379-86

- Schiff M, Peura D. HZT-501 (Duexis; ibuprofen 800 mg/famotidine 26.6 mg) GI protection in the treatment of the signs and symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis. Exp Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2012;6:25-35

- Merck & Co. Inc. Pepcid prescribing information. Whitehouse Station, NJ, USA: Merck & Co., 2007

- Bello AE, Holt RJ. Cardiovascular risk with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: clinical implications. Invited commentary. Drug Saf 2014;37:897-902

- Goldstein JL, Hochberg MC, Fort JG, et al. Clinical trial: the incidence of NSAID-associated endoscopic gastric ulcers in patients treated with PN 400 (naproxen plus esomeprazole magnesium) vs. enteric-coated naproxen alone. Aliment Pharmcol Ther 2010;32:401-13

- Deeks JJ, Smith LA, Bradley MD. Efficacy, tolerability, and upper gastrointestinal safety of celecoxib for treatment of osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis: systematic review of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 2002;325:1-8

- Bavry AA, Fridtjof T, Allison M, et al. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and cardiovascular outcomes in women: results from the Women’s Health Initiative. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2014;7:603-10

- Antman EM, Bennet JS, Daugherty A, et al. Use of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs: an update for clinicians: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2007;115:1634-42

- Manavathongcha S, Bian A, Rho YH, et al. Inflammation and hypertension in rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheum 2013;40:1806-11

- Lindhardsen J, Gislason GH, Jacobsen S, et al. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and risk of cardiovascular disease in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a nationwide cohort study. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:1515-21

- Deeks ED. Fixed-dose ibuprofen/damotidine: a review of its use to reduce the risk of gastric and duodenal ulcers in patients requiring NSAID therapy. Clin Drug Investig 2013;33:1173-2563