Abstract

Objective:

Evaluate efficacy of infliximab with response-driven dosing in patients with active RA.

Research design and methods:

Patients (n = 203) with active RA despite methotrexate + etanercept/adalimumab, participated in this active-infliximab-switch study. Infliximab 3 mg/kg was infused at Weeks 0, 2, 6, 14, and 22 with escalation to 5 or 7 mg/kg depending on EULAR response at Weeks 14 and 22. The primary endpoint was EULAR response at Week 10. Safety was assessed through Week 30. Infliximab levels and antibodies to infliximab (ATI) were measured at Weeks 0, 6, 14, and 26.

Clinical trial registration:

NCT 00714493, EudraCT 2007-003288-36.

Results:

Of 197 evaluable patients, 120/77 previously received etanercept/adalimumab. Baseline mean (SD) swollen and tender joint counts were 17.3 (10.54) and 30.2 (16.89), respectively; mean DAS28-ESR was 6.19 (0.981). At Week 10, 98 (49.7%; 95% CI: 42.6%, 56.9%) patients achieved EULAR response, with a significantly improved DAS28-ESR score (mean [SD] change −1.1 [1.15]; p < 0.001). EULAR response was achieved by 41.7%/62.3% of patients previously receiving etanercept/adalimumab (p = 0.006). At Week 26, 51.8% (95% CI: 44.6%, 58.9%) of patients achieved or maintained EULAR response. Infliximab dose was escalated in 100 patients, 52% of whom achieved EULAR response at Week 26. Median serum concentration levels at Week 26 showed that dose escalation helped EULAR non-responders achieve levels similar to or higher than the levels seen in responders. ATI were associated with lower serum concentrations of infliximab, consistent with lower efficacy rates among ATI-positive patients.

Conclusion:

Infliximab, in treat-to-target settings with individual dose escalation, demonstrated significant efficacy at Weeks 10 and 26 in patients switched to infliximab after inadequate response to etanercept/adalimumab. The observed efficacy indicated that the switch to infliximab and ability to increase dose in a targeted fashion were beneficial.

Key limitations:

Given the relatively short duration of study follow-up, these safety findings require confirmation in a longer-term study.

Introduction

Tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α inhibition has become the standard of care for rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients with an inadequate response to disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDS), such as methotrexate (MTX), since the approval of etanercept (Enbrel) in 1998, infliximab (RemicadeFootnote†) in 1999, and adalimumab (HumiraFootnote‡) in 2002Citation1,Citation2. As clinical experience with anti-TNF agents has increased, newer agents have been introduced, including certolizumab (CimziaFootnote§) and golimumab (SimponiFootnote⊥). Switching a patient from one to a second or a third anti-TNF agent or therapy with a different mechanism of action has become common in treating patients who lose efficacy or develop adverse events with their initial or second anti-TNF agentCitation3–8.

The benefits of switching among anti-TNF agents have been widely studied, particularly between etanercept and infliximabCitation9–14. Few studies, however, have evaluated an active switch (i.e., no washout period) of anti-TNF inadequate responders, and fewer still have utilized a prospective trial design in a large number of patients. No active-switch trial has utilized a treat-to-target approach with structured patient management in this challenging symptomatic patient population.

This trial was a multicenter, open-label, assessor-blinded, switch study to evaluate infliximab efficacy and safety in RA patients with an inadequate response to etanercept or adalimumab. Symptomatic RA patients, despite ongoing anti-TNF treatment, were identified to demonstrate the improved efficacy realized following an active switch to infliximab with the opportunity for two separate target-driven dose escalations. Pharmacokinetic assessment of infliximab levels and an evaluation of the presence of antibodies to infliximab (ATI) were conducted to further complete patient response profiles.

Patients and methods

Patients

Adults with a diagnosis of active RA, who demonstrated an inadequate response to ≥3 months of treatment with an approved, stable etanercept or adalimumab regimen in combination with ≥4 weeks of MTX (≥7.5 mg/week) were eligible to participate. An inadequate response was defined as a Disease Activity Score incorporating 28 joints and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (DAS28-ESR) ≥3.6, with ≥6 swollen joints and ≥6 tender joints. The last dose of etanercept/adalimumab must have been administered between 1 and 2 weeks and between 2 and 4 weeks, respectively, prior to receiving infliximab. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and/or oral corticosteroids (≤10 mg prednisone/day) were allowed at a stable dose for ≥4 weeks. Patients met all relevant tuberculosis and clinical laboratory test screenings. Patients who had ever received infliximab, certolizumab pegol, or more than one TNF inhibitor; treatment with abatacept, alefacept, efalizumab, or rituximab; or any investigational drug within 3 months of screening were excluded.

Study design and evaluations

The study (NCT 00714493, EudraCT 2007-003288-36) was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki and International Committee on Harmonization good clinical practices. The protocol was reviewed and approved by each site’s institutional review board or ethics committee. All patients provided written informed consent before undergoing any study-related procedure.

Patients received open-label infliximab 3 mg/kg at Weeks 0, 2, and 6. Patients not achieving a European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) clinical responseCitation15,Citation16 at Week 14 were eligible for infliximab dose escalation from 3 → 5 mg/kg. EULAR response was defined as:

>0.6 unit improvement in DAS28-ESR score if score at the time of assessment was ≤5.1, or

>1.2 unit improvement in DAS28-ESR score if score at the time of assessment was >5.1.

Patients who had not achieved/maintained a EULAR response at Week 22 could escalate infliximab dose from 3 → 5 mg/kg if still receiving 3 mg/kg or from 5 → 7 mg/kg if the infliximab dose had been increased to 5 mg/kg at Week 14. All patients continued a stable MTX regimen (≥7.5 mg/week).

The primary study endpoint was the proportion of patients who achieved a EULAR response based on DAS28-ESRCitation15,Citation17 at Week 10. Secondary efficacy endpoints included the proportions of patients achieving:

EULAR response at Weeks 10 and 26 without a dose increase,

EULAR response at Week 26, and

DAS28-ESR remission (defined as a score of <2.6)Citation16,Citation18 through Week 26.

Remission and low disease activity were defined as DAS-ESR scores of <2.6 and <3.2, respectively. Since both DAS28 and American College of Rheumatology (ACR) values based on ESR have been extensively validated for use in clinical trials, ESR was utilized for the present trial for these calculationsCitation16,Citation19.

Additional Week 10 and Week 26 endpoints included improvements in ACR criteriaCitation20, tender/swollen joint counts, changes in ESR, and changes in Simplified Disease Activity Index (SDAI)Citation21,Citation22 and Clinical Disease Activity Index (CDAI)Citation21–23. Joint evaluations were performed by an independent blinded assessor at each study site.

Improvement in functional status was assessed using the Disability Index of the Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ)Citation24, in which a clinically meaningful improvement was defined as a change of ≥0.22 units from baselineCitation25. Improvement in quality of life was assessed using the 36-item Short Form (SF-36) health surveyCitation26. Safety was evaluated at all study visits through Week 26, as well as via telephone questionnaire at Week 30.

Blood samples for clinical pharmacology assessments were collected immediately prior to each infusion at Weeks 0, 2, 6, 14, 16, and 22 and at Weeks 10 and 26 to evaluate drug concentrations and the development of ATI. ATI were detected using a double-antigen (bridging) enzyme immunoassay, as described previouslyCitation27.

Statistical analyses

Efficacy endpoints were assessed using the evaluable population, defined as a subset of the modified intent-to-treat (mITT) population that excluded six patients from one study site due to errors in study conduct. Data from the mITT (all enrolled patients who received ≥1 infliximab infusion) and per-protocol (a population with no major protocol deviations) populations were analyzed in sensitivity analyses of the primary efficacy endpoint.

Efficacy findings were summarized using descriptive statistics. In the primary efficacy analysis, patients considered treatment failures because of prohibited medication use or discontinuation due to lack of efficacy before Week 10 or with missing Week 10 DAS28 score were considered Week 10 EULAR nonresponders. The consistency of primary endpoint results was assessed across subgroups of patients defined by patient demographic and disease characteristics. Dose escalation at Week 14 and/or 22 was summarized via descriptive statistics for 156 evaluable patients who completed the study through Week 26.

Dichotomous efficacy endpoints of clinical response and remission were summarized as proportions and exact 95% confidence intervals (CIs); continuous parameters for change from baseline were analyzed using either paired t-tests or Wilcoxon signed-rank tests (α = 0.05). Safety analyses were performed for all patients who received ≥1 infliximab infusion. Adverse events (AEs) were summarized as counts and percentages by Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA, Version 10.1) system-organ class and preferred term.

The study was planned to enroll approximately 200 patients. No formal sample size calculations were performed. Sample size considerations were based on the OPPOSITE studyCitation11, an open-label pilot study of RA patients switched to infliximab following an incomplete response to etanercept. The sample size was increased eight-fold to better define the therapeutic benefit and safety of infliximab in patients with an inadequate response to etanercept. A similar sample size was planned for patients with an inadequate response to adalimumab, yielding an overall sample size of 200.

Results

Patient disposition and baseline characteristics

Study-related procedures commenced on 30 June 2008 and concluded on 7 June 2010. Two hundred three patients were enrolled: 160 (78.8%) patients at 39 sites in North America and 43 (21.2%) patients at 19 sites in Europe and Israel. All patients received ≥1 infliximab infusion and were included in the mITT population. Data for six patients enrolled and treated at a single site were excluded from efficacy analyses due to errors in study conduct. Thus, 197 patients were evaluable for efficacy.

Among these 197 patients, who ranged in age from 19–92 years, 156 (79.2%) were women, and 169 (85.8%) were white. Mean ± SD DAS28-ESR and HAQ scores were 6.2 ± 0.98 and 1.3 ± 0.58, respectively, at baseline (). The mean ± SD MTX dose at baseline was 15.5 ± 4.53 mg/week.

Table 1. Summary of patient characteristics at baseline; evaluable population.

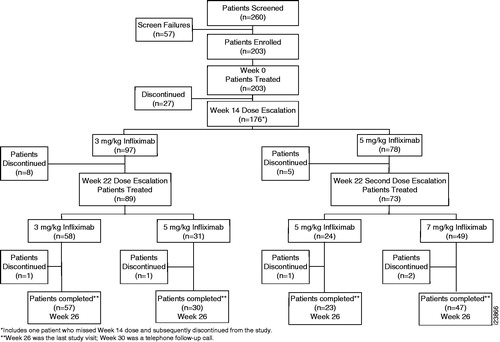

Among 203 enrolled patients, 45 (22.2%) discontinued the study prior to Week 26 (). Among 197 evaluable patients, 43 (21.8%) patients discontinued, most commonly because of a significant protocol violation (n = 12), AE (n = 10), withdrawn patient consent (n = 7), or lack of efficacy (n = 7). One hundred fifty-seven patients completed the study through the final infliximab infusion at Week 26 (). After excluding unevaluable and discontinued patients (prior to Week 26), 156 were eligible for efficacy assessment following dose escalation. Patients were contacted by telephone at Week 30 for follow-up to document serious and nonserious AEs.

Figure 1. Patient disposition through Week 26. Patients received open-label infliximab 3 mg/kg at Weeks 0, 2, and 6. Patients not achieving a European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) clinical response at Week 14 were eligible for infliximab dose escalation from 3 → 5 mg/kg. Patients who had not achieved or maintained EULAR response at Week 22 could also escalate infliximab from 3 → 5 mg/kg if still receiving 3 mg/kg or from 5 → 7 mg/kg if the infliximab dose had been increased to 5 mg/kg at Week 14.

Efficacy findings

Primary and secondary efficacy endpoints

At Week 10, 49.7% (98/197) (95% CI: 42.6%, 56.9%) of evaluable patients achieved EULAR response. The robust nature of the primary analysis was confirmed by sensitivity analyses using mITT and per-protocol populations ().

Table 2. Summary of infliximab efficacy at 10 and/or 26 weeks following active switch; evaluable population.

Among 98 evaluable patients who achieved EULAR response at Week 10, 44 (44.9%) maintained response through Week 26 without infliximab dose escalation. At Week 26, 102 (51.8%) evaluable patients achieved EULAR response, irrespective of prior response or dose escalation ().

Analyses indicated that the proportion of patients achieving EULAR response at Week 10 was similar among patient subgroups defined by gender, race, geographic region, body weight, and corticosteroid use at baseline. Conversely, higher response rates were observed in patients aged ≥65 years and patients with more severe disease (DAS28-ESR score >5.1) at baseline. Patients treated with adalimumab had a higher response rate than those treated previously with etanercept ().

At Week 10, DAS28-ESR remission was achieved by 6 (3.0%) patients. By Week 26, 9 (4.6%) patients achieved DAS28-ESR remission.

Among 197 evaluable patients, 56 (28.4%), 24 (12.2%), 3 (1.5%) and 1 (0.5%) patients achieved ACR20, ACR50, ACR70, and ACR90 responses, respectively, at Week 10. ACR response rates increased by Week 26, with 70 (35.5%), 36 (18.3%), 14 (7.1%), and 3 (1.5%) patients achieving ACR20, ACR50, ACR70, and ACR90 responses, respectively ().

For both SDAI and CDAI, significant reductions were observed from baseline to Week 26 (). At baseline, 87.8% (173/197) and 94.9% (187/197) of patients had high disease activity according to SDAI (>26) and CDAI (>22), respectively. At Week 26, 62.4% of patients experienced improvement in SDAI from high baseline disease activity, specifically, 28 (16.2%) patients with remission (SDAI ≤3.3), 31 (17.9%) with low disease activity (>3.3 to ≤11), and 49 (28.3%) with moderate disease activity (>11 to ≤26). Similar improvement in disease activity was observed with CDAI.

Assessment of EULAR response by dose escalation

Of 156 evaluable patients who completed Week 26, 102 (65.4%) achieved EULAR response. Approximately half (52/102) achieved response at Week 14 and maintained response throughout the trial. Escalation of the infliximab dose from 3 → 5 mg/kg (at Week 14 or 22) or from 5 → 7 mg/kg (at Week 22) was mandated by study protocol for patients with inadequate EULAR response. Among the 102 patients who achieved EULAR response at Week 26, 52 had infliximab-dose escalation from 3 → 5 mg/kg at Week 14 (n = 19) or Week 22 (n = 19) or from 3 → 5 mg/kg at Week 14 followed by escalation from 5 → 7 mg/kg at Week 22 (n = 14) (data not shown). These response patterns also show that 52 (33.3%) patients achieved EULAR response at Week 14 and maintained response through Week 26; 18 (11.5%) achieved EULAR response at Week 14, lost response at Week 22 but regained response at Week 26 with dose escalation; and 32 (20.5%) did not respond at Week 14 but responded at Week 26 after dose escalation (data not shown).

Approximately half (52/100, 52.0%) of patients who required dose escalation achieved EULAR response at Week 26. Nearly 83% (19 of 23) of patients who had infliximab-dose escalation from 3 → 5 mg/kg at Week 14 achieved EULAR response at Week 26. EULAR response was achieved for a majority (63.3%) of patients who had infliximab-dose escalated from 3 → 5 mg/kg at Week 22. Among the 47 patients who had their infliximab dose escalated a second time to 7 mg/kg, 14 (29.8%) achieved EULAR response at Week 26 ().

Table 3. Summary of EULAR response among 156 evaluable patients who completed the study through Week 26.

Physical function and quality of life

Infliximab therapy significantly improved patient physical function, with mean HAQ scores decreasing from 1.33 at baseline by −0.17 (95% CI: −0.24, −0.11; p < 0.001) at Week 10 and by −0.22, a clinically meaningful reduction (95% CI: −0.30, −0.14; p < 0.001), at Week 26. At Weeks 10 and 26, 39.1% and 40.1%, respectively, of evaluable patients achieved a clinically significant improvement (≥0.22 unit decrease) in HAQ scores ().

Table 4. Summary of physical function and quality of life in infliximab-treated patients following active switch; evaluable population.

As assessed using SF-36 domain scores, patient quality of life significantly improved by Week 10, with further improvement observed at Week 26. Specifically, patients had significant improvement (p < 0.001) in physical functioning, role–physical, bodily pain, and general health component scales at Week 10 and at Week 26 following the switch to infliximab (). Significant improvements in vitality, social functioning, role–emotional, and mental health SF-36 component scales were also observed at Week 10 and 26 ().

Clinical pharmacology assessments

Pharmacokinetics

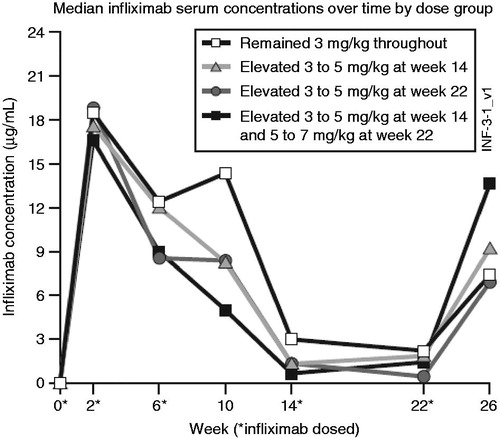

All patients initially received 3 mg/kg infliximab infusions at Weeks 0, 2, and 6. The median preinfusion serum infliximab concentrations in treated patients at Weeks 2, 6, and 14 were approximately 17.6, 10.8, and 1.7 µg/mL, respectively.

The profile of median infliximab serum concentrations over time characterized by patient responsiveness and consequent need for dose incrementation is depicted in . Compared with patients who achieved EULAR response with their original dose of 3 mg/kg infliximab and maintained that response throughout the trial, patients who did not achieve EULAR response and had a dose escalation (from 3 mg/kg → 5 mg/kg infliximab) at Week 14 had a lower median preinfusion serum infliximab concentration (approximately 1.3 versus 2.9 µg/mL). At Week 22, patients who did not achieve or maintain EULAR response also had lower median preinfusion serum infliximab concentrations at that assessment (approximately 0.33 µg/mL for patients whose dose increased from 3 mg/kg → 5 mg/kg and 1.4 µg/mL for patients whose dose increased from 5 mg/kg → 7 mg/kg at Week 22) compared with a median preinfusion serum infliximab concentration of approximately 2.2 µg/mL in patients who maintained EULAR response from Week 14 through Week 22.

Figure 2. Mean infliximab serum concentrations over time by dose group. Patients received doses at Weeks 0, 2, and 6 with escalations at Weeks 14 and 22 as necessary. The median concentrations represent pre-infusion trough levels.

Median serum concentration levels at Week 26 following dose escalations at Week 14 and Week 22 resulted in EULAR non-responders achieving serum infliximab levels similar to or higher than those seen in EULAR responders.

Immunogenicity

The effects of the therapeutic regimens utilized in this trial, including the response-driven increments at Week 14 and Week 22, on disease signs and symptoms and the development of ATI were examined during the 26 week study interval. Through 26 weeks, 195 of 203 (96.1%) patients were evaluable for ATI status determination, of whom 24 (12.3%) developed ATI after exposure to infliximab whereas none were ATI positive at baseline. One hundred fifty-six patients were evaluable for both EULAR and ATI assessments through Week 26 (), of whom only 17 (10.9%) patients were ATI positive. Whereas approximately two-thirds of ATI-non-positive (ATI-negative or inconclusive) patients were EULAR responders (60% at Week 10; 68% at Week 26) only a third of ATI-positive patients achieved EULAR response (35% at Week 10; 41% at Week 26). The presence of ATI was associated with lower serum concentrations of infliximab, consistent with the achievement of lower efficacy rates among ATI-positive patients ().

Table 5. Summary of EULAR responses through Week 26 by status of antibodies to infliximab (ATI).

Safety

Through Week 30, 143 (70.4%) of patients had ≥1 AE. Serious AEs were documented in 10 (4.9%) patients and AEs resulted in discontinuation of study agent in 19 (9.4%) of patients ().

Table 6. Summary of infliximab safety through 30 weeks following active switch, safety population.

Infections were documented for 65 (32.0%) patients. Infusion reactions were documented for 14 (6.9%) patients and in association with 15 of 925 (1.6%) infliximab infusions (). No serious infusion reactions were reported. No notable changes from baseline through Week 26 were documented for any hematology or clinical chemistry laboratory parameter.

Discussion

Efficacy and safety of infliximab plus MTX were evaluated in approximately 200 patients with difficult-to-treat RA, defined as active disease despite treatment with MTX and etanercept or adalimumab. The design of this prospective, open-label, assessor-blinded, switch study, which allowed infliximab dose escalation at Week 14 and/or Week 22 and included no washout period prior to treatment change, represents a clinically relevant approach to managing RA.

Approximately 50% of patients achieved EULAR response at Week 10, with response rates of 62% and 42% in patients who had previously received adalimumab and etanercept, respectively. Assuming that inadequate response to etanercept or adalimumab was attributable in part to antibody development, we expected a lower response rate among patients who switched from adalimumab to infliximab, both anti-TNF α monoclonal antibodies. Instead, the opposite was observed, indicating that switching these agents may be a reasonable treatment paradigm.

The percentage of patients achieving EULAR response at Week 26 (51.8%) was comparable to that observed at Week 10. Notably, approximately half of responding patients did not require dose escalation. Among those patients requiring infliximab dose escalation approximately half achieved EULAR response at Week 26. These findings are consistent with those reported in the START trialCitation28, which assessed infliximab dose escalation in RA patients with an inadequate response to infliximab 3 mg/kg or whose disease flared following an initial response. Approximately 30% of infliximab-treated patients in the START trial dose escalated, and 80% of these patients who received up to three 1.5 mg/kg dose escalations achieved ≥20% improvement in the total tender and swollen joint count after their last infliximab dose. In contrast, an analysis of data reported from the Stockholm biologics registry has shown improvement in efficacy following infliximab dose escalation to be small (mean improvement in DAS28 = 0.46)Citation29. The same analysis, however, showed that shortening the duration of time between infliximab doses was effective in sustaining response in 63% of patients.

Results of switching to infliximab those patients with an inadequate response to etanercept or adalimumab are also consistent with those from switch studies of other anti-TNF agents, including a change from open-label infliximab to etanerceptCitation9 and a change from open-label etanercept and/or infliximab to adalimumabCitation30. In addition, switching to other biologic RA treatments including the selective co-stimulation modulator abataceptCitation31, anti-interleukin-6 receptor antibody tocilizumabCitation32, and anti-CD20-B cell agent rituximabCitation33 following an inadequate response has been shown to be generally effective.

Historically, switch trials have employed a washout period to separate the end of the preceding anti-TNF therapy from the start of the new therapy. In contrast, our study design followed the prescribed dosing interval but did not require a washout period. This active switch is considered to be more consistent with actual clinical practice. Additionally, the current study successfully employed a treat-to-target paradigm, first assessing the effectiveness of the anti-TNF switch to infliximab through 14 weeks, then allowing a dose escalation of 2 mg/kg at Weeks 14 and 22 for patients who had not achieved EULAR response or whose response to treatment had diminished below the level of activity that defined response.

By week 10, 98 (49.7%) patients had achieved EULAR response with the 3 mg/kg induction dose of infliximab. Among the 98 patients who responded to the induction dose, approximately 22% with initial EULAR response were able to maintain response through the end of the study without dose escalation. Overall, 102 (52%) patients achieved EULAR response regardless of their initial EULAR response or increase in dose. These results are consistent with earlier registry-based trials indicating that the 3 mg/kg induction dose is a starting dose that is effective for some, but not all, patientsCitation34. Indeed, high percentages of patients remain on treatment for years if their dose of infliximab is adjusted adequately. For patients who require flexible dose increases to achieve an optimal response, cost of treatment should be taken into consideration and weighed against the best medical decisions for the patient to achieve sufficient disease controlCitation35.

Recently, an international task force of RA experts published a series of treat-to-target recommendations on the basis of evidence derived from a systematic literature review and expert opinionsCitation36. These recommendations focused upon regular follow-up examinations that employed composite measures of disease activity including joint counts, representing a systematic treatment approach not dissimilar to the patient treatment paradigm utilized in the current trial.

Improvement in RA signs/symptoms translated into improved physical function, with significant mean improvements at both Week 10 (−0.17 units) and Week 26 (−0.22 units) and approximately 40% of infliximab-treated patients achieving a clinically meaningful improvement (≥0.22-unit decrease) in the HAQ scoreCitation25 at both Weeks 10 and 26. These results are consistent with HAQ improvements reported previouslyCitation37 for patients switching anti-TNF therapy.

The pharmacokinetic assessment of infliximab concentrations demonstrated a pre-infusion median serum infliximab concentration profile comparable to that reported in an infliximab-naïve RA populationCitation38. However, within the current study population, those patients not achieving EULAR response generally had lower preinfusion serum concentrations compared with patients who achieved and maintained EULAR response. Dose escalations enabled non-responders to achieve infliximab levels similar to or higher than those observed in EULAR responders.

The incidence of ATI in this study was consistent with that in RA patients who received infliximab plus MTXCitation39. Historically, the presence of ATI has been associated with a higher index of therapeutic failure in RACitation40. The results of the current trial bear out this finding as the presence of ATI was associated with lower serum concentrations of infliximab and lower efficacy.

Conclusion

Infliximab demonstrated significant efficacy at Week 10 and Week 26 in RA patients who were switched to infliximab after inadequate response to etanercept/adalimumab. Improvements in efficacy and physical function were achieved with and without infliximab dose escalation. Infliximab dose escalation from 3 mg/kg to 5 mg/kg and/or 7 mg/kg was not associated with new safety signals. Given the relatively short duration of study follow-up, these safety findings require confirmation in a longer-term study.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This study was funded by Janssen Research & Development LLC and Merck/Schering Plough Research Institute Inc.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

R.F. has disclosed that he has received consulting fees and research grant support from Janssen. J.A.G. has disclosed that he has received consulting fees and/or research grants via the Atlanta Center for Clinical Research from Amgen, Astra Zeneca, Biogen-Idec, Janssen, Crescendo Bioscience, Genentech, Lilly, MEDI-IMUNE, Pfizer, and UCB. M.L.-R. has disclosed that she has received consulting fees from Janssen, Bristol-Myers-Squibb, MSD, and Roche. E.Z. has disclosed that she has received support from Janssen, Bristol-Myers-Squibb, Genentech, and Roche. H.E.-K. has disclosed that he has received consulting fees and research grant support from Janssen. R.B., R.D., J.W., and D.D. have disclosed that they were employees of Janssen Biotech Inc. at the time of this study. H.K. has disclosed that he has no significant relationships with or financial interests in any commercial companies related to this study or article.

CMRO peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Sumesh Kalappurakal, Linda Tang PhD, and Dave Zelinger PhD (Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC) for statistical support and Michelle Perate MS, Kirsten Schuck, and Mary Whitman PhD (Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC) for writing support, in all cases funded by Janssen Biotech Inc. The authors also thank the following study investigators who enrolled patients into the trial: Aelion J (Jackson TN USA), Amital H (Kfar Saba Israel), Baerwald C (Leipzig Germany), Baraf H (Wheaton MD USA), Bensen W (Hamilton, ON, Canada), Bertin P (Limoges France), Burkhardt H (Frankfurt Germany), Carreno L (Madrid Spain), Cauza E (Vienna Austria), Chattopadhyay C (Wigan UK), Cohen S (Tyler TX USA), Diab I (Middleburg Heights OH USA), Edwards W (Charleston SC USA), El-Kadi H (Freehold NJ USA), Elkayam O (Tel Aviv Israel), Emery P (Leeds UK), Fleischmann R (Dallas TX USA), Forstot J (Boca Raton FL USA), Goldman J (Atlanta GA USA), Gomez Reino JJ (La Coruna Spain), Hackshaw K (Columbus OH USA), Halter D (Houston TX USA), Kellner H (Muenchen Germany), Keystone E (Toronto ON Canada), Khraishi M (St. John’s NF Canada), Kimmel S (Tamarac FL USA), Langevitz P (Tel Hashomer Israel), Lespessailles E (Orleans France), Lieberman E (Berkeley Heights NJ USA), Lowenstein M (Palm Harbor FL USA), Majjhoo A (St. Claire Shores MI USA), Mandel D (Mayfield Village OH USA), Miniter M (Rock Island IL USA), Moreta E (Eagan MN USA), Murphy F (Duncansville PA USA), Nascimento J (Bridgeport CT USA), Neal J (Lexington KY USA), Neeck G (Hohenfelde Germany), Nguyen P (Reston VA USA), Pando J (Lewes DE USA), Patel R (Ft. Worth TX USA), Pegram S (Houston TX USA), Peters E (Paradise Valley AZ USA), Queiro R (Oviedo Spain), Reitblat T (Ashkelon Israel), Riccardi P (Syracuse NY USA), Rosner I (Haifa Israel), Ross J (Allentown PA USA), Ross S (St. Louis MO USA), Schneider R (St. Louis MO USA), Shergy W (Huntsville AL USA), Singhal A (Mesquite TX USA), Stern M (Springfield IL USA), Stupi A (Wexford PA USA), Tahir H (London UK), Thurmond-Anderle M (Amarillo TX USA), Tishler M (Beer Yaakov Israel), Troum O (Santa Monica CA USA), Vaz B (Tucson AZ USA), Wade J (Vancouver BC Canada), Waller P (Houston TX USA), Wassenberg S (Ratingen Germany), Zanetakis E (Tulsa OK USA), Zisman D (Haifa Israel).

Notes

*Enbrel is a registered trade name of Amgen Inc. and Pfizer Inc., Thousand Oaks, CA, USA

†Remicade is a registered trade name of Janssen Biotech, Inc., Horsham, PA, USA

‡Humira is a registered trade name of Abbott Laboratories, North Chicago, IL, USA

§Cimzia is a registered trade name of UCB Inc., Smyrna, GA, USA

⊥Simponi is a registered trade name of Janssen Biotech Inc., Horsham, PA, USA

References

- Hochberg MC, Tracy JK, Hawkins-Holt M, et al. Comparison of the efficacy of the tumour necrosis factor alpha blocking agents adalimumab, etanercept, and infliximab when added to methotrexate in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2003;62(Suppl 2):13-16

- Wiens A, Venson R, Correr CJ, et al. Meta-analysis of the efficacy and safety of adalimumab, etanercept, and infliximab for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Pharmacotherapy 2010;30:339-53

- Alivernini S, Laria A, Gremese E, et al. ACR70-disease activity score remission achievement from switches between all the available biological agents in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review of the literature. Arthritis Res Ther 2009;11:R163

- Erickson AR, Mikuls TR. Switching anti-TNF-alpha agents: what is the evidence? Curr Rheumatol Rep 2007;9:416-20

- Hyrich KL, Lunt M, Watson KD, et al; for the British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register. Outcomes after switching from one anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha agent to a second anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha agent in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: results from a large UK national cohort study. Arthritis Rheum 2007;56:13-20

- Scrivo R, Conti F, Spinelli FR, et al. Switching between TNFalpha antagonists in rheumatoid arthritis: personal experience and review of the literature. Reumatismo 2009;61:107-17

- Chatzidionysiou K, Askling J, Eriksson J, et al.; for the ARTIS group. Effectiveness of TNF inhibitor switch in RA: results from the national Swedish register. Ann Rheum Dis 2014: published online 15 January 2014, doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204714

- Conti F, Scrivo R, Spinelli FR, et al. Outcome in patients with rheumatoid arthritis switching TNF-alpha antagonists: a single center, observational study over an 8-year period. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2009;27:540-1

- Bingham CO III, Ince A, Haraoui B, et al. Effectiveness and safety of etanercept in subjects with RA who have failed infliximab therapy: 16-week, open-label, observational study. Curr Med Res Opin 2009;25:1131-42

- Cohen G, Courvoisier N, Cohen JD, et al. The efficiency of switching from infliximab to etanercept and vice-versa in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2005;23:795-800

- Furst D, Gaylis N, Bray V, et al. Open-label, pilot protocol of patients with rheumatoid arthritis who switch to infliximab after an incomplete response to etanercept: the OPPOSITE study. Ann Rheum Dis 2007;66:893-9, comment in: Ann Rheum Dis 2007;66:849-51

- Hansen KE, Hildebrand JP, Genovese MC, et al. The efficacy of switching from etanercept to infliximab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 2004;31:1098-102

- Laas K, Peltomaa R, Kautiainen H, et al. Clinical impact of switching from infliximab to etanercept in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Rheumatol 2008;27:927-32

- van Vollenhoven R, Harju A, Brannemark S, et al. Treatment with infliximab (Remicade) when etanercept (Enbrel) has failed or vice versa: data from the STURE registry showing that switching tumour necrosis factor α blockers can make sense. Ann Rheum Dis 2003;62:1195-8

- Van Gestel AM, Prevoo ML, van’t Hof MA, et al. Development and validation of the European League Against Rheumatism response criteria for rheumatoid arthritis. Comparison with the preliminary American College of Rheumatology and the World Health Organization/International League Against Rheumatism criteria. Arthritis Rheum 1996;39:34-40, comment in: Arthritis Rheum 1998;41:942-5

- Prevoo ML, van’t Hof MA, Kuper HH, et al. Modified disease activity scores that include twenty-eight-joint counts: development and validation in a prospective longitudinal study of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1995;38:44-8

- van Gestel A, Stucki G. Evaluation of established rheumatoid arthritis. Bailliere’s Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 1999;13:629-44

- van Riel PL, van Gestel AM, Scott DL. EULAR Handbook of Clinical Assessments in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Alphen Aan Den Rijn, The Netherlands: Van Zuiden Communications BV, 2000

- Felson DT, Anderson JJ, Boers M, et al. The American College of Rheumatology preliminary core set of disease activity measures for rheumatoid arthritis clinical trials. The Committee on Outcome Measures in Rheumatoid Arthritis Clinical Trials. Arthritis Rheum 1993;36:729-40

- Felson DT, Anderson JJ, Boers M, et al. American College of Rheumatology. Preliminary definition of improvement in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1995;38:727-35

- Smolen JS, Breedveld FC, Schiff MH, et al. A simplified disease activity index for rheumatoid arthritis for use in clinical practice. Rheumatology 2003;42:244-57

- Aletaha D, Smolen JS. The Simplified Disease Activity Index (SDAI) and Clinical Disease Activity Index (CDAI) to monitor patients in standard clinical care. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2007;21:662-75

- Aletaha D, Nell VP, Stamm T, et al. Acute phase reactants add little to composite disease activity indices for rheumatoid arthritis: validation of a clinical activity score. Arthritis Res Ther 2005;7:R796-806

- Fries JF, Spitz P, Kraines RG, et al. Measurement of patient outcome in arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1980;23:137-45

- Wells GA, Tugwell P, Kraag GR, et al. Minimum important difference between patients with rheumatoid arthritis: the patient’s perspective. J Rheumatol 1993;20:557-60

- Ware JE Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form healthy survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care 1992;30:473-83

- Hanauer SB, Wagner CL, Bala M, et al. Incidence and importance of antibody responses to infliximab after maintenance or episodic treatment in Crohn’s Disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2004;2:542-53

- Westhovens R, Yocum D, Han J, et al. The safety of infliximab, combined with background treatments, among patients with rheumatoid arthritis and various comorbidities: a large, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum 2006;54:1075-86, erratum in Arthritis Rheum 2007;56:1675

- van Vollenhoven RF, Klareskog L. Infliximab dosage and infusion frequency in clinical practice: experiences in the Stockholm biologics registry STURE. Scand J Rheumatol 2007;36:418-23

- Bombardieri S, Ruiz AA, Fardellone P, et al. Effectiveness of adalimumab for rheumatoid arthritis in patients with a history of TNF-antagonist therapy in clinical practice. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2007;46:1191-9

- Genovese MC, Schiff M, Luggen M, et al. Efficacy and safety of the selective co-stimulation modulator abatacept following 2 years of treatment in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and an inadequate response to anti-tumour necrosis factor therapy. Ann Rheum Dis 2008;67:547-54

- Emery P, Keystone E, Tony HP, et al. IL-6 receptor inhibition with tocilizumab improves treatment outcomes in patients with rheumatoid arthritis refractory to anti-tumour necrosis factor biologicals: results from a 24-week multicentre randomised placebo-controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2008;67:1516-23

- Cohen SB, Emery P, Greenwald MW, et al. Rituximab for rheumatoid arthritis refractory to anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy: results of a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III trial evaluating primary efficacy and safety at twenty-four weeks. Arthritis Rheum 2006;54:2793-806

- Stern R, Wolfe F. Infliximab dose and clinical status: results of 2 studies in 1642 patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 2004;31:1538-45

- Gilbert TD Jr, Smith D, Ollendorf DA. Patterns of use, dosing, and economic impact of biologic agent use in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Musculoskel Dis 2004;5:36

- Smolen JS, Aletaha D, Bijlsma JW, et al. Treating rheumatoid arthritis to target: recommendations of an international task force. Ann Rheum Dis 2010;69:638-43

- Hyrich KL, Lunt M, Dixon WG, et al; on behalf of the BSR Biologics Register. Effects of switching between anti-TNF therapies on HAQ response in patients who do not respond to their first anti-TNF drug. Rheumatology 2008;47:1000-5

- Smolen JS, van der Heijde DM, St Clair EW, et al. Active-controlled study of patients receiving infliximab for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis of early onset (ASPIRE) study group. Arthritis Rheum 2006;54:702-10

- Maini RN, Breedveld FC, Kalden JR, et al. Therapeutic efficacy of multiple intravenous infusions of anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha monoclonal antibody combined with low-dose weekly methotrexate in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1998;41:1552-63

- van der Laken CJ, Voskuyl AE, Roos JC, et al. Imaging and serum analysis of immune complex formation of radiolabelled infliximab and anti-infliximab in responders and non-responders to therapy for rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2007;66:253-6