Abstract

The Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act provides a pathway for regulatory approval of generic drugs and the associated patent challenge. This article reviews strategic considerations during the patent litigation and injunction phases. Considerations during the initial patent litigation phase include when and whether to exchange a paragraph k application and the listing and exchange of patent information during the volley phase.

Keywords::

The Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA) provides a regulatory pathway for the approval of biosimilar versions of biologic drugs in the United States Citation[1]. This new pathway, which has yet to have its first applicant, provides a new trail for the approval of biosimilars and presents important strategic considerations for navigating the intellectual property-protected route to market. This article examines some of these considerations for both the biosimilar applicant and the sponsor of the reference biologic drug (or reference product sponsor, ‘RPS’).

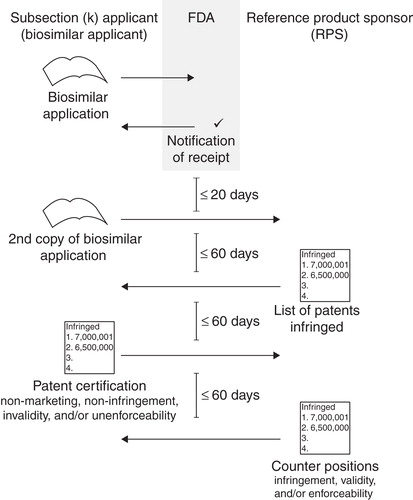

The BPCIA specifies the content requirements for a biosimilar applicant in submitting a complete dossier to the United States Food & Drug Administration (FDA) Citation[2]. Once FDA notifies the applicant that the dossier has been accepted for review, a complex process for litigating, and resolving, any patent infringement claims between the biosimilar applicant and the RPS begins. First, the biosimilar applicant must disclose to the RPS, within 20 days of FDA's notification, a copy of the application and related manufacturing processes, and possibly additional information as requested by the RPS Citation[3]. The first strategic consideration is thus whether and when to produce the application and other information to the RPS.

The BPCIA sets forth specific penalties for non-compliance, including that the RPS can assert any patent that claims the biological product or its use, and is not limited to those patents identified in the pre-litigation patent exchange process (described below) Citation[4]. The BPCIA also has a sweeping, catch-all penalty for non-compliance, providing that one convicted of violating any provision shall be punished by a fine not exceeding $500 and/or imprisonment up to 1 year Citation[5]. We do not suggest such a draconian penalty of prison will become commonplace in BPCIA-related patent litigation between sophisticated litigants, but this statutory language provides an impetus for rapid compliance. The BPCIA also addresses the scenario where the application is disclosed but the applicant otherwise fails to comply with certain sections of the Act, in which case the applicant's ability to seek a declaration of patent invalidity or no infringement may be limited Citation[6]. Assuming an applicant can still defend against a charge of infringement, but not seek an affirmative declaration to that effect (e.g., assert an affirmative defense vs seek a declaratory judgment), then an applicant may accordingly alter its BPCIA strategy.

The section of the BPCIA outlining the patent exchange process presents many opportunities for strategic action. Here the applicant and the RPS are to agree upon or negotiate which patents to litigate in a first-wave or immediate patent litigation, and which to later litigate in a second-wave or preliminary injunction phase. In the first-wave litigation, the process is further broken down into what we have dubbed the volley phase and the negotiation phase. In the volley phase, there are three exchanges between the parties regarding which patents to litigate, each equally spaced 60 days apart (). The first overture is from the RPS to the applicant, identifying which patents could reasonably be asserted and which the RPS would be prepared to license Citation[7]. From a strategic perspective, the critical question the RPS asks itself is whether to identify all, or less than all, the patents that could be reasonably asserted.

Figure 1. Schematic illustrating the ‘Volley Phase’ of document exchanges between biosimilar applicant and reference product sponsor.

If the applicant fails later in this process, then the RPS may assert only the patents in this first list. This may prompt over-inclusion Citation[8]. The BPCIA further promotes this strategy by limiting the patents in the second-wave litigation to those on the either party's initial list and not included in the first-wave litigation. The BPCIA thus provides an incentive for the RPS to initially list all possible patents, perhaps reserving some for the second-wave litigation should the first-wave proceed undesirably. Such a strategy is cautioned, however, because the patent code provides that the RPS may not be able to sue (at least before commercialization) on a patent not included in the first list Citation[9].

The applicant must also have a strategy when it responds to the RPS' initial list and license statement. In the license statement, the RPS need only identify which patents it would be prepared to license, and need not include any term that could conceivably be construed as an offer. The applicant's response will likely be equally non-substantive. What will be substantive is the applicant's arguments—on a claim by claim basis—to each patent included in the RPS' initial list. Applicant must argue that the patent is invalid, not infringed or unenforceable (or assurances that commercial marketing will not begin until patent expiration). Because the RPS is not initially required to identify which specific claims might be infringed, then the applicant's response may become irrelevant because rarely does a patentee assert every claim of every patent. As such, the applicant's pre-filing legal efforts will undoubtedly be extensive. The last part of the applicant's response, though not required, is its own identification of patents in response to the RPS' list Citation[10]. But why would the applicant identify any additional patents that could reasonably be asserted? One reason is that the applicant seeks legal certainty on a patent omitted (either inadvertently or intentionally) from the RPS' list. Another reason is to force the RPS to detail its infringement arguments during its last volley and before any litigation ensues.

The third and last volley before the negotiation phase is for the RPS to respond to the infringement (on a claim-by-claim basis), invalidity and unenforceability arguments as to each patent on its initial list and on the applicant's list. This undertaking will be equally extensive, as the RPS must anticipate invalidity and unenforceability arguments that may never be made. Thus, from a strategic perspective, the RPS applicant may seek to minimize the initial patent list and the attendant burdens. Nevertheless, the applicant's and the RPS' lists together limit the patents in the negotiation phase, and ultimately in the first-wave and second-wave litigations.

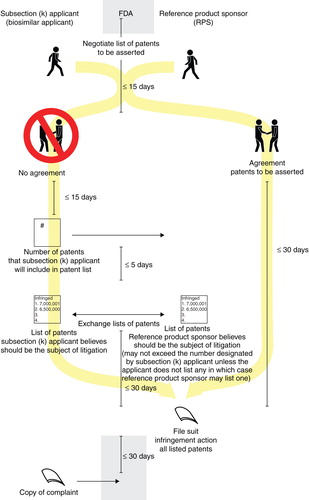

In the negotiation phase, the RPS and the applicant negotiate for 15 days regarding which patents from their lists should be in the first-wave litigation (). If they agree, then the RPS has 30 days to file a lawsuit on those patents. If there is no agreement, then the applicant notifies the RPS of the number of patents (but not the specific patents themselves) to be litigated Citation[11]. In this scenario, the applicant has the strategic advantage of controlling the number of patents in the first-wave litigation, though knowing that the balance of patents may be litigated in the second-wave. Five days after that number is disclosed, then the RPS and the applicant simultaneously exchange their respective lists of specific patents. There is no requirement that the RPS list as many patents as designated by the applicant. Further, if the applicant designates no patents for the first-wave, the RPS may designate a single patent Citation[12]. After the exchange, the RPS has 30 days to file a lawsuit on the patents on the lists, thus triggering the first-wave litigation.

Figure 2. Schematic illustrating the “Negotiation Phase” between biosimilar applicant and reference product sponsor.

The second-wave litigation will likely occur much later, perhaps several years after the first-wave litigation. This is because the triggering event for the second-wave is notice from the applicant to the RPS “not later than 180 days before the date of the first commercial marketing” of the biosimilar product Citation[13]. Once that notice is provided, the RPS may seek a preliminary injunction against the applicant as to any patent on either of their initial volley lists but not included in the negotiation phase (and thus not in the first-wave litigation) Citation[14]. Such litigation is probably several years away because no biosimilar application has yet been publicly disclosed, and because the review time at FDA will likely be more than a year (for reference purposes, a typical NDA or BLA application now takes approximately 15 months for approval Citation[15]), meaning the first commercial marketing of a biosimilar product is more than 1 year away. For the last strategic consideration in this comment, because the commercial notice is to be given not later than 180 days before the first commercial marketing of the biosimilar product, could an applicant give the required notice immediately after initiation of the first-wave litigation? To avoid unnecessary (and costly) patent litigation, perhaps such notice is more likely to arrive when there is reasonable certainty for approval. After all, an applicant would probably not undertake the expense of a second-wave litigation unless the related product were commercially viable and a possible source of funding.

In sum, the BPCIA, and particularly its patent exchange process, are complex and offer many scenarios where strategic considerations need to be fully vetted in advance.

Declaration of interest

This article is for educational purposes only. JL Marquardt is a registered United States Patent Attorney in private practice at Marquardt Law. SR Auten is also a registered United States Patent Attorney in private practice. The opinions expressed herein are the opinion of the authors alone and not necessarily those of their respective firms or clients. The authors state no conflict of interest and have received no payment in preparation of this manuscript.

Bibliography

- Gaudry KS. Exclusivity strategies and opportunities in view of the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation act. Food Drug L J 2011;66:587-630; for an overview of the BPCIA

- 42 U.S.C. 262(k)(2)

- 42 U.S.C. 262(l)(2)

- 42 U.S.C. 262(l)(9)(C)

- 42 U.S.C. 262(f)

- 42 U.S.C. 262(l)(9)(B)

- 42 U.S.C. 262(l)(3)(A)

- 42 U.S.C. 262(l)(8)(B)

- 35 U.S.C 271(e)(6)(C)

- 42 U.S.C. 262(l)(3)(B)

- 42 U.S.C. 262(l)(5)(A)

- 42 U.S.C. 262(l)(5)(B)(ii)(II)

- 42 U.S.C. 262(l)(8)(A)

- 42 U.S.C. 262(l)(8)(B)

- “Trends in NDA and BLA Submissions and Approval Times”. Available from: http://www.fda.gov/AboutFDA/ReportsManualsForms/Reports/UserFeeReports/PerformanceReports/PDUFA/ucm209349.htm