Abstract

Introduction: Several long-acting injectable (LAI) second-generation antipsychotics are now available for the management of schizophrenia. As patients with schizophrenia frequently present with diverse and challenging symptoms, it is important to understand the effects of antipsychotics in treating these different symptom subgroups and the timing of these responses.

Areas covered: For this review, data from two randomized, double-blind trials were analyzed in respect to the onset and persistence of effects on several measures of psychopathology (as measured by the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale [PANSS]) after treatment with LAI paliperidone palmitate (PP) (NCT00590577 and NCT00589914).

Expert opinion: Symptom reductions from baseline with PP were significant by day 4 for all five PANSS factors in both studies. Some effects may have been driven by the presence or absence of a placebo response. A significant effect for PP versus placebo was observed for all major symptom domains for one or more doses of PP during the first month of treatment. Once established, most (but not all) significant responses persisted to the end point. Similar improvements were observed in PANSS scores with PP and oral risperidone. Dose-dependent trends were observed for the effect of PP on positive, negative and uncontrolled hostility/excitement symptoms.

1. Introduction

1.1 Schizophrenia

Schizophrenia is a chronic, severely disabling disorder that results in unfavorable outcomes for many patients. It places a high care burden on family members and a large economic burden on society as a whole Citation[1,2]. Clinicians treating this complicated patient population are challenged by the wide range of clinical symptoms with which it presents and variability in the clinical course of the disease Citation[3]. Symptoms are individually difficult to manage, often leading to complex polypharmacy. Nowadays, symptoms are usually categorized in positive symptoms (e.g., hallucinations, delusions), negative symptoms (e.g., emotional withdrawal, lack of spontaneity), disorganized thinking (e.g., poor attention, conceptual disorganization) and cognitive symptoms (e.g., memory, abstract thinking, decision making) domains. Mood symptoms, including uncontrolled hostility/excitement and anxiety/depression, are frequently observed in patients with schizophrenia Citation[4,5].

Although many antipsychotic medications have been studied over the past 60 years, the onset/duration and extent of response and the dose response for each major symptom category remain poorly understood. Comprehensive evaluation of response following treatment with antipsychotic medications should address these considerations.

1.2 Symptom measurement

The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) is a validated scale commonly used in clinical trials with antipsychotic medications. Factor analysis of this scale has identified five symptom dimensions in patients with schizophrenia (positive symptoms, negative symptoms, disorganized thoughts, uncontrolled hostility/excitement and anxiety/depression) Citation[4]. These factors or symptom domains can be used in characterizing differences in extent and onset of response after treatment with antipsychotic medications. Using data from two large clinical trials, this review examines the timing and extent of treatment response and dose response for paliperidone palmitate (PP) () compared with baseline symptoms versus placebo and oral risperidone in schizophrenia.

Box 1. Drug summary.

1.3 Adherence and the role of long-acting injectable antipsychotic medications

Previous studies have suggested that inadequate responses and poor outcomes remain commonplace for schizophrenia. Such poor outcomes may be due not to treatment resistance but to poor adherence to prescribed treatments Citation[6-8]. The best medications cannot be effective if not taken consistently. Adequate adherence to treatment is especially problematic in schizophrenia treatment. Indeed, the most vulnerable persons with schizophrenia (i.e., recent onset of illness, illness still in a progressive stage and comorbid problems of substance abuse) are among those at greatest risk for poor adherence Citation[7,8]. Treatment decision making is complicated when adherence to treatment is uncertain. If response is incomplete, questions like these must be addressed: Should the dose be elevated? Should the medication be changed or supplemented? Is education on better medication adherence needed?

Long-acting injectable (LAI) antipsychotic medications can help address the key problem of poor adherence by providing the clinician with certain knowledge of adherence and requiring adherence only once every 2 – 4 weeks Citation[9]. If a patient becomes nonadherent, the clinician has a wider time frame in which to contact the patient to encourage returning to treatment before plasma levels drop substantially.

Tolerability with LAI medications, particularly with initiation at high doses, can be a matter of concern to clinicians and patients. Clinical data suggest comparable tolerability between oral and injectable antipsychotics Citation[10-12]. Efficacy with LAI compared with oral antipsychotics has been the focus of much research. Although it has been hypothesized that LAI formulations can offer efficacy advantages over daily oral formulations, this hypothesis is based on the theoretical advantages associated with removing the need for daily adherence. The data are mixed Citation[12-22]; however, studies with designs that are most reflective of real-world treatment conditions suggest that LAI formulations may lower the potential for symptom relapse and may lead to a shorter relapse duration and a reduction in the length and frequency of hospitalizations Citation[14,15,23-28].

1.4 LAI formulations of antipsychotic medications

First-generation LAI formulations of antipsychotics, such as fluphenazine decanoate and haloperidol decanoate, were introduced in the 1960s. Their use has been limited by a high incidence of extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS), poor patient tolerability and ill-defined treatment initiation guidelines Citation[29,30]. Currently available second-generation LAI antipsychotics include formulations of risperidone, paliperidone, olanzapine and aripiprazole. Second-generation LAI antipsychotics have reduced some key tolerability concerns associated with older agents such as EPS, leading to lower rates of treatment discontinuation. However, it is well recognized that some treatment-related adverse events (AEs) such as weight gain and prolactin elevations occur more commonly with some of the newer-generation LAIs Citation[30-32]. Rates of treatment-induced metabolic AEs and prolactin elevations vary within the broad group of second-generation agents. Higher rates of metabolic AEs are particularly evident for olanzapine and clozapine Citation[30,31], and elevated prolactin is particularly evident for risperidone and paliperidone Citation[32,33].

2. Paliperidone palmitate

2.1 Formulation and pharmacokinetics

PP (9-hydroxy risperidone) is a once-monthly, LAI nanocrystal formulation of paliperidone that is maintained in an aqueous suspension. After intramuscular (i.m.) injection, PP is hydrolyzed to paliperidone, allowing for precise dissolution with an extended half-life of 25 – 49 days, depending on the dose Citation[34-36]. This nanocrystal technology provides an increased surface area that allows rapid release of the drug, resulting in rapid achievement of steady-state plasma levels Citation[34,35,37].

As a consequence of these pharmacokinetic properties, initial supplementation with oral antipsychotic medication is not necessary for symptom control with PP Citation[37]. Release starts as early as day 1 and lasts as long as 126 days Citation[37].

2.2 PP dosing

PP treatment is initiated with an i.m. injection dose of 234 mg (150 mg eq) into the deltoid muscle on treatment day 1, followed by a second injection (dose varied by study) into the deltoid muscle on day 8. Monthly maintenance dose ranges from 39 mg (25 mg eq) to 234 mg (150 mg eq) into the deltoid or gluteal muscle, according to individual patient preference and/or tolerability Citation[37]. Current or previous oral antipsychotic medications can be discontinued when PP injections are initiated. Patients who are naïve to risperidone and paliperidone or their LAI forms should receive test doses to ensure tolerability and the absence of hypersensitivity reactions Citation[37].

2.3 Overall trial results of PP treatment

In short-term studies, PP LAI given according to the dosing schedule provided sustained plasma concentrations and documented improvement in clinical outcomes, such as a reduction in symptoms of schizophrenia, with an efficacy and safety profile similar to flexibly dosed risperidone long-acting injection (RLAI) Citation[10,11,38-41]. The AEs of PP were similar to those of oral paliperidone, oral risperidone and RLAI Citation[10,11]. Further, during long-term studies, PP LAI was shown to reduce the probability of disease relapse, improve patient functioning and reduce hospitalization Citation[42-44].

2.4 Onset of efficacy effects with PP

2.4.1 Overview

Results and post hoc analyses from two randomized, double-blind, short-term controlled trials Citation[38,45-49] were used for establishing the current recommended initiation dosing for PP. Assessments with the PANSS allowed examination of onset of efficacy in five key efficacy domains. In both studies, patients older than18 years of age who had been given a primary diagnosis of schizophrenia (according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition [DSM-IV]) more than 1 year before screening were enrolled.

2.4.2 PP response versus placebo

2.4.2.1 Overview

This 13-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study (NCT00590577) assessed three fixed doses of PP in patients with acute exacerbation of an established primary diagnosis of schizophrenia, with a PANSS total score between 70 and 120 (inclusive) at screening and between 60 and 120 at baseline (inclusive). Key exclusion criteria included a history of treatment resistance to two adequate courses of different antipsychotic medications with a minimum duration of 4 weeks at the patient’s maximum tolerated dose (MTD); a DSM-IV diagnosis of active substance dependence within 3 months before study screening; suicidal, homicidal or other violent ideation or risk for such behavior; a history of neuroleptic malignant syndrome; a history of significant or unstable systemic disease and body mass index (BMI) ≥ 40. Primary study results have been reported Citation[38].

In the active treatment arms, PP was administered at 234 mg on day 1 (deltoid), at the assigned dose (39, 156 or 234 mg) on day 8 (deltoid or gluteal; a deviation from current labeling recommendations) and once monthly thereafter (deltoid or gluteal). PANSS scores were collected at baseline and on days 4, 8, 22, 36, 64 and 92/end point. Data for the three PP arms were pooled for days 4 and 8 measures because all subjects received 234 mg on day 1. Between-group differences were assessed using analysis of covariance, and within-group differences from baseline were assessed using paired t-tests. Last observation carried forward (LOCF) values were used. No adjustments were made for multiple comparisons. Effect sizes were utilized to evaluate treatment versus placebo differences at end point.

2.4.2.2 Response of overall symptoms

Mean baseline PANSS score was 87.1 across the PP groups and 86.8 in the placebo group Citation[38]. Within-group improvement from baseline to each time point for PP treatment as measured by change in PANSS total score was consistently significant. A significant placebo response compared with baseline was also observed at all time points, with the exception of end point (p = 0.0571) (Janssen Scientific Affairs, data on file).

Relative to placebo, PP was associated with significantly greater improvement in overall symptoms as measured by PANSS total scores (p = 0.037) by day 8. This improvement persisted until end point for all PP dose groups. It should be noted that, given the pharmacokinetics of PP, responses observed at day 8 were exclusively driven by the 234-mg dose given on day 1 to all subjects () Citation[45].

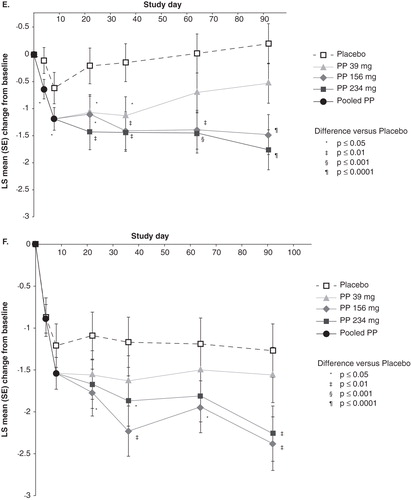

Figure 1. Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) total and factor scores are shown Citation[38,45,46] a,b. A. Total Score (30 items; score range, 30 – 210) is shown. Mean (SD) score at baseline: 87.2 (11.5) for PP and 86.8 (10.3) for placebo. B. Positive Symptom Factor Score (eight items; score range, 8 – 56) is shown. Mean (SD) score at baseline: 26.3 (5.0) for PP and 26.5 (5.5) for placebo. C. Negative Symptom Factor Score (seven items; score range, 7 – 49) is shown. Mean (SD) score at baseline: 20.9 (5.3) for total PP and 20.4 (5.1) for placebo. D. Disorganized Thoughts Factor Score (seven items; score range, 7 – 49) is shown. Mean (SD) score at baseline: 20.1 (4.7) for total PP and 19.8 (4.3) for placebo. E. Uncontrolled Hostility/Excitement Factor Score (four items; score range, 4 – 28) is shown. Mean (SD) score at baseline: 9.3 (3.2) for total PP and 9.3 (3.3) for placebo. F. Anxiety/Depression Factor Score (four items; score range, 4 – 28) is shown. Mean (SD) score at baseline: 10.6 (3.3) for total PP and 10.8 (3.3) for placebo.

![Figure 1. Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) total and factor scores are shown Citation[38,45,46] a,b. A. Total Score (30 items; score range, 30 – 210) is shown. Mean (SD) score at baseline: 87.2 (11.5) for PP and 86.8 (10.3) for placebo. B. Positive Symptom Factor Score (eight items; score range, 8 – 56) is shown. Mean (SD) score at baseline: 26.3 (5.0) for PP and 26.5 (5.5) for placebo. C. Negative Symptom Factor Score (seven items; score range, 7 – 49) is shown. Mean (SD) score at baseline: 20.9 (5.3) for total PP and 20.4 (5.1) for placebo. D. Disorganized Thoughts Factor Score (seven items; score range, 7 – 49) is shown. Mean (SD) score at baseline: 20.1 (4.7) for total PP and 19.8 (4.3) for placebo. E. Uncontrolled Hostility/Excitement Factor Score (four items; score range, 4 – 28) is shown. Mean (SD) score at baseline: 9.3 (3.2) for total PP and 9.3 (3.3) for placebo. F. Anxiety/Depression Factor Score (four items; score range, 4 – 28) is shown. Mean (SD) score at baseline: 10.6 (3.3) for total PP and 10.8 (3.3) for placebo.](/cms/asset/69f01a05-37a1-4513-828e-d5c170280a5d/ieop_a_909409_f0001_b.jpg)

2.4.2.3 Response for individual symptom factors compared with baseline

Significant within-group improvement from baseline was observed by day 4 on the five PANSS symptom factors after PP treatment was initiated with 234 mg and persisted to end point for all dose groups with no oral antipsychotic supplementation () Citation[46].

Significant within-group improvement versus baseline was also observed for placebo for positive symptom and anxiety/depression factor scores at all time points. Significant within-group improvement versus baseline was observed for placebo at day 22 for the negative symptom factor and at days 4 and 8 for the disorganized thoughts factor Citation[46].

2.4.2.4 Response for individual symptom factors compared with placebo

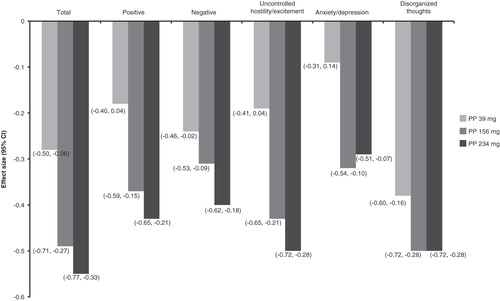

All PANSS factor scores improved in one or more PP treatment arms versus placebo. Onset of response varied by symptom domain and by dose Citation[46]. Significant improvements relative to placebo were observed by day 4 for uncontrolled hostility/excitement (after 234 mg day 1 injection; p < 0.05) and by day 8 for negative symptoms (after 234 mg day 1 injection; p < 0.05). At day 22, response to one or more doses of PP relative to placebo was superior for positive symptoms, disorganized thoughts, uncontrolled hostility/excitement and anxiety/depression Citation[46]. Once significant responses were observed, most (but not all) persisted until end point. At day 92/end point, response to one or more doses of PP relative to placebo was superior for all symptom factor domains (, ) Citation[46]. Evaluation of effect sizes at end point for PANSS factor scores suggests a dose-dependent trend for the three dose groups evaluated ().

Figure 2. Effect sizes at end point (13 weeks) for positive and negative syndrome scale total and factor scores for paliperidone palmitate versus placebo*.

Table 1. Significant treatment responses relative to placebo by symptom domain and paliperidone palmitate dosea,b.

The lowest PP dose (39 mg) showed an inconsistent response across symptom domains. Improvement was not significant compared with placebo for positive symptom and anxiety/depression factors at any time point and was inconsistent for hostility/excitement and negative symptoms Citation[46]. On the other hand, improvements in PANSS total score and in disorganized thoughts factor score with PP 39 mg were superior to placebo from day 22 to end point Citation[45].

2.4.3 PP versus oral risperidone

2.4.3.1 Overview

This randomized, double-blind study (NCT00589914) compared response to flexibly dosed PP and flexibly dosed RLAI in patients with an established diagnosis of schizophrenia, a PANSS total score at screening and baseline of between 60 and 120 (inclusive), and a BMI ≥ 17 and < 40. Exclusion criteria included a primary active DSM-IV Axis I diagnosis other than schizophrenia; a reduction of at least 25% in PANSS total score between screening and baseline; active substance dependence within 3 months before screening; a history of treatment resistance (failure to respond to two adequate treatments with different antipsychotic medications, each administered for ≥ 6 weeks at MTD); a relevant history of significant or unstable systemic disease and a significant risk of suicidal or violent behavior. Previous use of PP or exposure within the previous 6 months to any experimental drug or device was disallowed. Mood stabilizers, including lithium or anticonvulsants, were to be discontinued before randomization. Primary study results were previously published Citation[47].

Patients randomized to RLAI received their first RLAI injection on day 8 with oral risperidone supplementation for the first 28 days of treatment (starting on day 1) Citation[47]. Because of the release profile of RLAI and the injection schedule used in this study, effects through day 28 in the RLAI arm can be attributed to oral risperidone. This treatment group is referred to below as the ‘oral risperidone’ treatment group.

PP was initiated at 234 mg on day 1 (deltoid) and 156 mg on day 8 (deltoid only) without oral supplementation, followed by monthly flexible dosing at 78 – 234 mg (deltoid or gluteal) Citation[47]. This analysis focused on data obtained during days 1 – 22 (PP vs oral risperidone). PANSS scores were evaluated at days 4, 15 and 22. Between-group differences were assessed using analysis of covariance, and within-group differences from baseline were assessed using paired t-tests. LOCF values were used. No multiplicity adjustment was made for comparisons.

2.4.3.2 Response for overall symptoms

Mean baseline PANSS score was 84.9 in the PP group and 83.5 in the oral risperidone group Citation[47]. Within-group improvement in overall symptoms from baseline to days 4, 15 and 22 was evident for both PP and oral risperidone, as measured by changes in PANSS total score () Citation[48]. The extent of improvement was similar for both treatments.

Table 2. Least square mean change from baseline in positive and negative syndrome scale total and factor scores.

2.4.3.3 Response of individual symptom domains compared with baseline

Within-group improvement from baseline in individual symptom groupings was significant for both PP and oral risperidone from baseline to days 4, 15 and 22, as measured by changes in PANSS factor scores (all p values < 0.01; least squares means change in ) Citation[49].

2.4.3.4 Response of individual symptom domains compared with oral risperidone

Between-group differences for PP and oral risperidone were observed at day 4 for only PANSS positive symptoms (least squares mean [standard error] change for PP vs oral risperidone: –0.8 [0.1] vs –0.6 [0.1]; p = 0.02) and disorganized thoughts (–0.5 [0.1] vs –0.3 [0.1]; p = 0.04) factor scores. These differences favored PP Citation[49]. No significant between-group differences were observed for the other factor scores or at any other time point ().

Because the study was not placebo-controlled, the study effect specific to PP or oral risperidone cannot be determined.

3. Tolerability of PP

Tolerability data from these two studies were previously published; an overview is provided here Citation[38,47]. As described in the package insert, the most common (≥ 5% in any PP group) and likely drug-related (AEs for which the drug rate is at least twice the placebo rate) AEs were injection-site reactions, somnolence/sedation, dizziness, akathisia and extrapyramidal disorder Citation[37].

3.1 PP versus placebo

In the comparison of PP versus placebo, all three doses of PP were generally well tolerated, with most treatment-emergent AEs (TEAEs) mild-to-moderate in severity Citation[38]. The overall incidence of TEAEs appeared similar between PP and placebo (60.0 – 63.2% vs 65.2%). Rates of discontinuation due to TEAEs appeared similar across all treatment groups (6.1 – 8.0% vs 6.7%). Common TEAEs that were more frequent with PP versus placebo included injection-site pain (7.6 vs 3.7%), dizziness (2.5 vs 1.2%), sedation (2.3 vs 0.6%), pain in extremity (1.6 vs 0.0%) and myalgia (1.0 vs 0.0%). The most commonly reported EPS-related AE across all treatment groups was akathisia, with an incidence rate of < 6%. A dose-related increase in the incidence of weight gain was observed with PP versus placebo (6 – 13% vs 5%), and no glucose-related TEAEs were reported with PP treatment. Mean increases in prolactin levels from baseline to end point were seen in all PP groups; increases were larger in women (change from baseline, 4.72 – 37.24 ng/ml) than in men (change from baseline, 3.73 – 13.15 ng/ml). Mean prolactin levels decreased in the placebo group irrespective of sex.

3.2 PP versus oral risperidone

The incidence of individual AEs was generally similar between groups, with the exception of insomnia, anxiety and injection-site pain, which occurred at a higher incidence (difference ≥ 2%) in PP compared to oral risperidone groups Citation[48].

4. Conclusion

Patients with schizophrenia typically present with diverse symptoms. Individual expression and response to treatment can be extremely variable. Therefore, evaluating the effect of an antipsychotic with respect to both extent and onset is important for guiding treatment decisions. The studies reviewed here suggest that symptomatic reduction in all major symptom domains can be observed as early as day 4 following treatment with PP in the absence of oral supplementation. Response appeared similar in extent and onset to that for oral risperidone and persisted at higher doses (156 and 234 mg) for the duration of treatment. With a few notable exceptions, once significant responses were observed, they persisted to the end of the observation period.

5. Expert opinion

This report largely represents a review of post hoc analyses of studies on PP completed for regulatory submissions. Persons studied were not randomly selected from the general population of persons with schizophrenia. They were likely less treatment-resistant, had fewer comorbidities and were likely more adherent to treatment than the general population of persons with schizophrenia. Also, analyses of effects were not adjusted for multiplicity. Therefore, any significant effects identified must be considered as nominal, and results should be considered as hypothesis-generating rather than definitive. Nevertheless, the work provides valuable insights to guide clinical decision making and future directions for research.

Use of LAI antipsychotic medications remains limited, in part because injectable formulations may not be as well accepted by some patients as their oral counterparts Citation[50]; however, acceptance rates are high in patients who have experience with an LAI, and many patients may be open to the use of an LAI antipsychotic if asked by their physician Citation[51-53]. Growing evidence indicates that effective doctor–patient communication is a crucial factor in patient acceptance of treatment Citation[54-58], and that physician ambivalence may negatively influence patient acceptance Citation[59]. In addition, the higher cost of LAI antipsychotic medications may sometimes preclude their use, even though cost-effectiveness studies have reported lower hospital and outpatient care costs for patients receiving LAIs compared with oral formulations Citation[60,61]. The use of LAI antipsychotic medications is also limited in part by uncertainty regarding onset and persistence of clinical response and management of dosing. This review provides important insights into these and other considerations.

5.1 Early onset of effect with PP

Knowledge of expected onset of treatment response represents a key clinical consideration for LAI antipsychotics and supports medication management by addressing questions such as: When am I likely to see some evidence of clinical improvement? When am I likely to observe near-maximal clinical response with this dose of antipsychotic? This knowledge is critical for decisions regarding when to increase medication doses, when to supplement treatment with concomitant medications or when to remove them and when to switch antipsychotic medications.

Knowledge about onset of effect is particularly important for LAI formulations of antipsychotics. Their pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties are obviously different from those of oral formulations, and, just as critical, differences from one LAI formulation to another can be dramatic. For example, release of RLAI is delayed for about 3 weeks, and pharmacodynamic effects cannot be expected until after that time. For PP, release begins as early as day 1 and is sustained to allow once-monthly maintenance dosing. The clinical question is whether pharmacodynamic responses for PP in the absence of supplementation can be anticipated to have an onset similar to that for oral antipsychotics.

These analyses suggest that the pharmacodynamic effects of PP can be observed as early as day 4 – the first time point when symptoms were assessed after injection of PP Citation[38,45,46]. Particularly intriguing is the observation that onset of response may vary by symptom domain. Early onset of response seems to be partially driven by the responsivity of uncontrolled hostility/excitement and by the low placebo response in this key clinical domain, which is a frequent driver for hospitalization and is critical for patient management.

At higher doses of PP, significant treatment response was observed for all other symptom domains, although response for most was not significant until day 8 or day 22 Citation[46].

Results from study NCT00589914 suggest that treatment effects appeared similar for both oral risperidone and PP Citation[47-49]. Indeed, in this study, onset of response for positive symptoms and disorganized thought symptoms was noted at day 4 for PP, which is faster than for oral treatment Citation[49].

5.2 Persistence of effect for PP

Because of potential differences between initiation and maintenance doses of PP, persistence of effect can be a central clinical consideration for treatment management with this LAI. The initiation regimen with high loading doses (234 mg on day 1 and 156 mg on day 8) allows rapid achievement of therapeutic plasma levels, but steady state is not achieved for approximately five half-lives. Thus, steady-state plasma levels for lower doses of PP, especially 39-mg doses, may be lower than those attained after the first weeks of treatment. Consequently, pharmacodynamic responses observed with the initiation regimen may be lost over time. This work suggests that, if treatment response is achieved, it persists to end point, particularly with higher monthly maintenance doses. An exception is that symptoms of uncontrolled hostility/excitement initially responded to treatment in the 39-mg arm because of administration of 234 mg at day 1, but the response was lost after day 36 Citation[46].

5.3 No oral supplementation of PP needed

An important finding from these analyses was that onset of effect for PP without oral antipsychotic supplementation could be achieved with an effect size similar to that of oral risperidone Citation[48,49]. This is a valuable attribute because oral supplementation raises numerous treatment management concerns, including: i) management of discontinuation of oral medication; ii) possible requirements for dosage readjustments following discontinuation of supplemental treatment; and iii) the need to observe for drug–drug interactions if the oral supplement is chemically different from PP.

5.4 Dose response for symptom improvement

A key consideration with any medication is identification of the appropriate dose for optimal treatment response. Results from this work suggest that maximal treatment response with PP is dose-dependent and that symptom subgroups are differentially responsive to dose Citation[45,46]. Maximal response was observed for most symptom domains after treatment with 234 mg. In general, response to 39 mg was weak, with no evidence demonstrated for treating either positive symptoms or symptoms of anxiety/depression. Response for negative symptoms and uncontrolled hostility/excitement was inconsistent at this dose. The dose-dependent effect is supported by larger effect sizes seen with higher doses.

Symptoms of disorganization were particularly sensitive to PP treatment. Significant responses were observed by day 22 at all doses but were most evident at higher doses Citation[46]. In this analysis, symptoms of anxiety/depression and negative symptoms seemed the least responsive to PP. However, lesser evidence for efficacy in these domains may have been secondary to low prevalence and/or severity of these symptoms among subjects and to strong placebo response in some symptom domains.

5.5 Placebo response

Yet another observation from this work was that placebo response varied by symptom domain. Little or no placebo response was evident for symptoms of uncontrolled hostility/excitement or disorganized thoughts, whereas relatively high levels of placebo response were observed for positive symptoms and for symptoms of anxiety/depression Citation[46]. This is the converse of findings for specific treatment effect and suggests that the strength of the treatment response observed with PP was driven in part by the presence or absence of a placebo response for that symptom grouping. This finding is consistent with other reports. For example, Kozielska et al. reported that PANSS items associated with uncontrolled hostility/excitement PANSS factors were least responsive to placebo Citation[62]. Placebo response by domain may help identify symptoms that can best serve for screening putative novel antipsychotic treatments.

Although placebo response can be a valuable tool for clinical management, its extent is not consistent nor is it generally persistent over time Citation[63]. The complex nature and increasing magnitude of this phenomenon in the field of antipsychotic medicine Citation[64,65] have resulted in an increasing number of failed trials Citation[64,65]. It appears that methodological factors may in part explain differences in placebo response Citation[64,65]. However, placebo responses of a similar magnitude and pattern to those observed in the trials examined here have been demonstrated in similarly designed PP studies in comparable, ethnically diverse patient populations Citation[66,67]. This lends support to the generalizability of the placebo effect observed in this study and to the conclusion drawn regarding the efficacy of PP relative to placebo.

5.6 AEs with PP

No unanticipated AE responses were observed compared with prior studies of PP. Further, at the doses studied, no evidence of dose response was found for the AEs observed in these clinical trials. However, as described in the package insert, based on pooled data from the four fixed-dose, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials, among the AEs that occurred, only akathisia and hyperprolactinemia increased with dose Citation[37].

5.7 Limitations and unanswered questions

Although the analyses reviewed here provide valuable clinical insights into treatment response with PP, they must be regarded as preliminary and should be followed by additional research. The most significant limitations of this work relate to its generalizability and applicability to specific patients. As already noted, the population reported here was not drawn from a random sample of all persons with schizophrenia and thus may not be fully representative of the schizophrenia population. This consideration is likely exaggerated by the fact that, in current clinical practice, LAI antipsychotics are often reserved for patients who are less compliant and who have more psychiatric comorbidities. Such subjects were specifically excluded from these trials. Data from more pragmatically designed trials would be helpful in enhancing the generalizability of this work. Further, patients evaluated in these studies were likely enriched for having positive symptoms. Other symptom subgroups may or may not have been evident. Thus, responses observed may be limited by the severity of the specific symptoms evident in the study population at baseline.

Another limitation worthy of mention is that of the statistically significant, yet very small, differences demonstrated with respect to PANSS positive symptoms and disorganized thoughts at day 4 in the noninferiority study between LAI PP and oral risperidone. As no adjustment for multiple testing was performed, these results must be interpreted with caution; extrapolation to support a difference in onset of action between the two medications may be inappropriate, particularly as all other domains showed no difference between treatment groups.

Finally, one important question that cannot be answered by our analysis is that of the most appropriate timing for a treatment switch in cases of poor response. Additional studies will be required to establish the most appropriate course of action in such patients. In general, this must be evaluated on a case-by-case basis with close collaboration between patient and clinician.

Declaration of interest

Development of this manuscript was supported by Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC. L Alphs, CA Bossie, D-J Fu and JK Sliwa are employees of Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC and are Johnson & Johnson stockholders. Y-W Ma is an employee of Janssen Research & Development, LLC and is a Johnson & Johnson stockholder. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

Acknowledgment

Writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript. The authors thank Matthew Grzywacz, PhD, Sheena Hunt, PhD, Max Chang and ApotheCom, LLC, for providing writing and editorial assistance that was funded by Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC.

Notes

Bibliography

- Chan SW. Global perspective of burden of family caregivers for persons with schizophrenia. Arch Psychiatr Nurs 2011;25:339-49

- Knapp M, Mangalore R, Simon J. The global costs of schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 2004;30:279-93

- Van der Velde CD. Variability in schizophrenia: reflection of a regulatory disease. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1976;33:489-96

- Marder SR, Davis JM, Chouinard G. The effects of risperidone on the five dimensions of schizophrenia derived by factor analysis: combined results of the North American trials. J Clin Psychiatry 1997;58:538-46

- Nasrallah HA. The primary and secondary symptoms of schizophrenia: current and future management. Suppl Curr Psychiatry 2011;10:S5-9

- Van Putten T. Why do schizophrenic patients refuse to take their drugs? Arch Gen Psychiatry 1974;31:67-72

- Corriss DJ, Smith TE, Hull JW, et al. Interactive risk factors for treatment adherence in a chronic psychotic disorders population. Psychiatry Res 1999;89:269-74

- Marder SR, Mebane A, Chien CP, et al. A comparison of patients who refuse and consent to neuroleptic treatment. Am J Psychiatry 1983;140:470-2

- Kim S, Solari H, Weiden PJ, Bishop JR. Paliperidone palmitate injection for the acute and maintenance treatment of schizophrenia in adults. Patient Prefer Adherence 2012;6:533-45

- Nussbaum AM, Stroup TS. Paliperidone palmitate for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;6:CD008296

- Carter NJ. Extended-release intramuscular paliperidone palmitate: a review of its use in the treatment of schizophrenia. Drugs 2012;72:1137-60

- Kane JM, Detke HC, Naber D, et al. Olanzapine long-acting injection: a 24-week, randomized, double-blind trial of maintenance treatment in patients with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 2010;167:181-9

- Rosenheck RA, Krystal JH, Lew R, et al. Long-acting risperidone and oral antipsychotics in unstable schizophrenia. N Engl J Med 2011;364:842-51

- Kirson NY, Weiden PJ, Yermakov S, et al. Efficacy and effectiveness of depot versus oral antipsychotics in schizophrenia: synthesizing results across different research designs. J Clin Psychiatry 2013;74:568-75

- Kishimoto T, Nitta M, Borenstein M, et al. Long-acting injectable versus oral antipsychotics in schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of mirror-image studies. J Clin Psychiatry 2013;74:957-65

- Kishimoto T, Robenzadeh A, Leucht C, et al. Long-acting injectable vs oral antipsychotics for relapse prevention in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. Schizophr Bull 2014;40:192-213

- Bitter I, Katona L, Zambori J, et al. Comparative effectiveness of depot and oral second generation antipsychotic drugs in schizophrenia: a nationwide study in Hungary. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2013;23:1383-90

- Gaebel W, Schreiner A, Bergmans P, et al. Relapse prevention in schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder with risperidone long-acting injectable vs quetiapine: results of a long-term, open-label, randomized clinical trial. Neuropsychopharmacology 2010;35:2367-77

- Olivares JM, Rodriguez-Morales A, Diels J, et al. Long-term outcomes in patients with schizophrenia treated with risperidone long-acting injection or oral antipsychotics in Spain: results from the electronic Schizophrenia Treatment Adherence Registry (e-STAR). Eur Psychiatry 2009;24:287-96

- Zhu B, Scher-Svanum H, Shi L, et al. Time to discontinuation of depot and oral first-generation antipsychotics in the usual care of schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv 2008;9:315-17

- Macfadden W, Ma YW, Thomas HJ, et al. A prospective study comparing the long-term effectiveness of injectable risperidone long-acting therapy and oral aripiprazole in patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatry 2010;7:23-31

- Keks NA, Ingham M, Khan A, Karcher K. Long-acting injectable risperidone v. olanzapine tablets for schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder: randomised, controlled, open-label study. Br J Psychiatry 2007;191:131-9

- Fusar-Poli P, Kempton MJ, Rosenheck RA. Efficacy and safety of second-generation long-acting injections in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis of randomized-controlled trials. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 2013;28:57-66

- Prikryl R, Prilrylova KH, Vrzalova M, Ceskova E. Role of long-acting injectable second-generation antipsychotics in the treatment of first-episode schizophrenia: a clinical perspective. Schizophr Res Treatment 2012;2012:764769

- Leucht C, Heres S, Kane JM, et al. Oral versus depot antipsychotic drugs for schizophrenia: a critical systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised long-term trials. Schizophr Res 2011;127:83-92

- Tiihonen J, Haukka J, Taylor M, et al. A nationwide cohort study of oral and depot antipsychotics after first hospitalization for schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 2011;168:603-9

- Lafeuille MH, Laliberte-Auger F, Lefebvre P, et al. Impact of atypical long-acting injectable versus oral antipsychotics on rehospitalization rates and emergency room visits among relapsed schizophrenia patients: a retrospective database analysis. BMC Psychiatry 2013;13:221

- Grimaldi-Bensouda L, Rouillon F, Astruc B, et al. Does long-acting injectable risperidone make a difference to the real-life treatment of schizophrenia? Results of the Cohort for the General Study of Schizophrenia (CGS). Schizophr Res 2012;134:187-94

- Taylor D. Psychopharmacology and adverse effects of antipsychotic long-acting injections: a review. Br J Psychiatry Suppl 2009;52:S13-19

- Leucht S, Corves C, Arbter D, et al. Second-generation versus first-generation antipsychotic drugs for schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Lancet 2009;373:31-41

- Zhang JP, Gallego JA, Robinson DG, et al. Efficacy and safety of individual second-generation versus first-generation antipsychotics in first-episode psychosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2013;16:1205-18

- Perez-Iglesias R, Mata I, Martinez-Garcia O, et al. Long-term effect of haloperidol, olanzapine, and risperidone on plasma prolactin levels in patients with first-episode psychosis. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2012;32:804-8

- Berwaerts J, Cleton A, Rossenu S, et al. A comparison of serum prolactin concentrations after administration of paliperidone extended-release and risperidone tablets in patients with schizophrenia. J Psychopharmacol (Oxf) 2010;24:1011-18

- Park EJ, Amatya S, Kim MS, et al. Long-acting injectable formulations of antipsychotic drugs for the treatment of schizophrenia. Arch Pharm Res 2013;36:651-9

- Chue P, Chue J. A review of paliperidone palmitate. Expert Rev Neurother 2012;12:1383-97

- Samtani MN, Vermeulen A, Stuyckens K. Population pharmacokinetics of intramuscular paliperidone palmitate in patients with schizophrenia: a novel once-monthly, long-acting formulation of an atypical antipsychotic. Clin Pharmacokinet 2009;48:585-600

- Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc. INVEGAR SUSTENNAR (paliperidone palmitate) extended-release injectable suspension, for intramuscular use. Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Titusville, NJ; 2012

- Pandina GJ, Lindenmayer JP, Lull J, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled study to assess the efficacy and safety of 3 doses of paliperidone palmitate in adults with acutely exacerbated schizophrenia. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2010;30:235-4

- Nasrallah HA, Gopal S, Gassmann-Mayer C, et al. A controlled, evidence-based trial of paliperidone palmitate, a long-acting injectable antipsychotic, in schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology 2010;35:2072-82

- Kramer M, Litman R, Hough D, et al. Paliperidone palmitate, a potential long-acting treatment for patients with schizophrenia. Results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled efficacy and safety study. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2010;13:635-47

- Gopal S, Vijapurkar U, Lim P, et al. A 52-week open-label study of the safety and tolerability of paliperidone palmitate in patients with schizophrenia. J Psychopharmacol (Oxf) 2011;25:685-97

- Hough D, Gopal S, Vijapurkar U, et al. Paliperidone palmitate maintenance treatment in delaying the time-to-relapse in patients with schizophrenia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Schizophr Res 2010;116:107-17

- Nicholl D, Nasrallah H, Nuamah I, et al. Personal and social functioning in schizophrenia: defining a clinically meaningful measure of maintenance in relapse prevention. Curr Med Res Opin 2010;26:1471-84

- Kozma CM, Slaton T, Dirani R, et al. Changes in schizophrenia-related hospitalization and ER use among patients receiving paliperidone palmitate: results from a clinical trial with a 52-week open-label extension (OLE). Curr Med Res Opin 2011;27:1603-11

- Bossie CA, Sliwa JK, Ma YW, et al. Onset of efficacy and tolerability following the initiation dosing of long-acting paliperidone palmitate: post-hoc analyses of a randomized, double-blind clinical trial. BMC Psychiatry 2011;11:79

- Sliwa JK, Bossie CA, Fu DJ, et al. Onset of efficacy on specific symptoms domains with long-acting injectionable palperidone palmitate in subjects with schizophrenia. Poster presented at: 14th International Congress on Schizophrenia Research; 21 – 25 April 2013; Orlando, FL

- Pandina G, Lane R, Gopal S, et al. A double-blind study of paliperidone palmitate and risperidone long-acting injectable in adults with schizophrenia. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2011;35:218-26

- Gopal S, Pandina G, Lane R, et al. A post-hoc comparison of paliperidone palmitate to oral risperidone during initiation of long-acting risperidone injection in patients with acute schizophrenia. Innov Clin Neurosci 2011;8:26-33

- Alphs L, Fu DJ, Sliwa JK, et al. Onset of efficacy in schizophrenia symptom domains with long-acting injectable paliperidone palmitate vs oral risperidone. Poster presented at: American Psychiatric Association 166th Annual Meeting; 18 – 22 May 2013; San Francisco, CA

- Weiden PJ, Schooler NR, Weedon JC, et al. A randomized controlled trial of long-acting injectable risperidone vs continuation on oral atypical antipsychotics for first-episode schizophrenia patients: initial adherence outcome. J Clin Psychiatry 2009;70:1397-406

- Potkin S, Bera R, Zubek D, Lau G. Patient and prescriber perspectives on long-acting injectable (LAI) antipsychotics and analysis of in-office discussion regarding LAI treatment for schizophrenia. BMC Psychiatry 2013;13:261

- Chue P, Emsley R. Long-acting formulations of atypical antipsychotics: time to reconsider when to introduce depot antipsychotics. CNS Drugs 2007;21:441-8

- Heres S, Schmitz FS, Leucht S, Pajonk FG. The attitude of patients towards antipsychotic depot treatment. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 2007;22:275-82

- Kunt T, Snoek FJ. Barriers to insulin initiation and intensification and how to overcome them. Int J Clin Pract Suppl 2009;164:6-10

- Hamann J, Cohen R, Leucht S, et al. Do patients with schizophrenia wish to be involved in decisions about their medical treatment? Am J Psychiatry 2005;162:2382-4

- Hamann J, Cohen R, Leucht S, et al. Shared decision making and long-term outcome in schizophrenia treatment. J Clin Psychiatry 2007;68:992-7

- Hamann J, Mendel RT, Fink B, et al. Patients’ and psychiatrists’ perceptions of clinical decisions during schizophrenia treatment. J Nerv Ment Dis 2008;196:329-32

- McNeil BJ, Pauker SG, Sox HC Jr, Tversky A. On the elicitation of preferences for alternative therapies. N Engl J Med 1982;306:1259-62

- Weiden PJ, Roma RS, Velligan DI, et al. The challenge of offering long acting antipsychotic therapies: A discourse analysis of psychiatrist recommendations of injectable therapy to patients with schizophrenia. Presented at the 2011 US Psychiatric and Mental Health Congress; 7 – 10 November 2011; Las Vegas, NV

- Lin J, Wong B, Offord S, Mirski D. Healthcare cost reductions associated with the use of LAI formulations of antipsychotic medications versus oral among patients with schizophrenia. J Behav Health Serv Res 2013;40:355-66

- Offord S, Wong B, Mirski D, et al. Healthcare resource usage of schizophrenia patients initiating long-acting injectable antipsychotics vs oral. J Med Econ 2013;16:231-9

- Kozielska M, Pilla RV, Johnson M, et al. Sensitivity of individual items of the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) and items subgroups to differentiate between placebo and drug treatment in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 2013;146:53-8

- Alphs L, Benedetti F, Fleischhacker WW, Kane JM. Placebo-related effects in clinical trials in schizophrenia: what is driving this phenomenon and what can be done to minimize it? Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2012;15:1003-14

- Kemp AS, Schooler NR, Kalali AH, et al. What is causing the reduced drug-placebo difference in recent schizophrenia clinical trials and what can be done about it? Schizophr Bull 2010;36:504-9

- Khin NA, Chen YF, Yang Y, et al. Exploratory analyses of efficacy data from schizophrenia trials in support of new drug applications submitted to the US Food and Drug Administration. J Clin Psychiatry 2012;73:856-64

- Gopal S, Hough DW, Xu H, et al. Efficacy and safety of paliperidone palmitate in adult patients with acutely symptomatic schizophrenia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-response study. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 2010;25:247-56

- Takahashi N, Takahashi M, Saito T, et al. Randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study assessing the efficacy and safety of paliperidone palmitate in Asian patients with schizophrenia. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2013;8:1889-98