1. Introduction

Rasagiline (RAS) is a Parkinson's drug with a moderate symptomatic effect, good tolerance and a potentially disease-modifying action. The therapy is indicated in monotherapy and in combination therapy with both levodopa and a dopamine agonist. The value of this substance is not unanimously rated internationally despite the uniform results.

2. History

The efficacy of monoamine oxidase type B (MAO-B) inhibitors has been known for decades, and these agents have been established in the treatment of Parkinson's disease for > 20 years. Contrary to quite a few other substances, however, MAO-B inhibitors have always remained the focus of discussion. A disease-modifying effect had been discussed right from the start. The initial success of selegiline in the 1990s was followed by a setback, triggered by a publication on the increased mortality rate in the selegiline group. The statements were repeatedly modified. RAS was finally approved in Europe on 21, February 2005. The studies needed for approval were TVP-1012 in Early Monotherapy for Parkinson disease Outpatient (TEMPO) Citation[1], Parkinson's Rasagiline: Efficacy and Safety in the Treatment of “Off” (PRESTO) Citation[2] and Lasting effect in Adjunct therapy with Rasagiline Given Once daily (LARGO) Citation[3]. After RAS had entered the market, the former discussions about disease modification were resumed again and were also supported by a number of in vivo and in vitro studies.

3. Data constellation

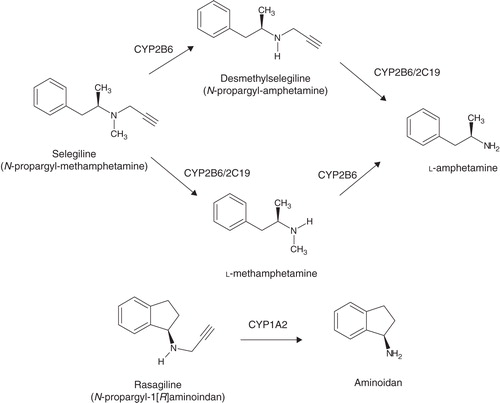

RAS (N-propargyl-1-[R]-aminoindane) is an irreversible, selective MAO-B inhibitor Citation[4]. The potential of MAO-B inhibition of RAS is 5 – 10 times greater than that of selegiline Citation[4]. Its bioavailability comes to ∼ 36% and is not hampered by meals. Metabolism predominantly happens in the liver, aminoindane being the metabolite () rather than amphetamine derivatives Citation[5]. The true value of aminoindane has still not been established.

Some long-term clinical studies were meanwhile published related to patients who had been partially observed for several years. Above all, these include TEMPO, PRESTO, LARGO and Attentuation of Disease progression with Azilect Given Once daily (ADAGIO):

The TEMPO study Citation[1], in which 404 patients were enrolled, was aimed at proving the efficacy and safety of monotherapy. Significant improvement of motor symptoms was corroborated for both doses (1 and 2 mg). The study was continued with interesting results: All patients – the placebo group included – received RAS. After a year, a significant difference became obvious between these groups, in favor of those patients who had been treated with RAS right from the beginning. In the further course, about 50% of the patients remained on monotherapy with RAS after 2 years, 23% after 4 years and 13% after 6 years Citation[6].

LARGO Citation[3] and PRESTO Citation[2] are studies which verified a positive effect of RAS when applied in the form of combination therapy (prolongation of the on time). ANDANTE (Add on to Dopamine Agonists in the Treatment of Parkinson's disease) was able to demonstrate that additional medication with RAS improved motor effects for patients on dopamine agonists Citation[7]. ANDANTE was an 18-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized study with 328 patients (RAS n = 163, placebo n = 165). RAS versus placebo was given as an add-on therapy to a stable dose of dopamine agonist in early Parkinson's disease. RAS showed a statistically significant improvement in the Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) motor examination subscale (Part III) (p = 0.007). In total, the UPDRS score (Parts I, II and III) was -2.4 ± 0.95 [95% confidence interval (CI) -4.3, -0.5; p = 0.012]. There were no significant differences between groups for the activities of daily living (ADLs) (p = 0.301) or Clinical Global Impression (CGI-I) scores. RAS was well tolerated in the study. No significant differences in adverse events, when compared to placebo, were seen Citation[7].

The LARGO study even substantiated comparable effects of RAS and entacapone Citation[3]. These studies furthermore maintain that the levodopa-saving effect for levodopa is higher with RAS than with selegiline.

One thousand one hundred seventy-six patients participated in the ADAGIO study Citation[8] – a prospective study with delayed-start design. These patients had symptoms for, on average, 4.5 months (SD ± 4.6) and presented with a total UPDRS score of 20.4 (SD ± 8.5). The study was run over 72 weeks and showed a significantly better clinical outcome when 1 mg RAS was administered, although the placebo group was also given RAS after 36 weeks. The group receiving 2 mg RAS did not show a significantly better outcome after 72 weeks. There have been quite a lot of speculations regarding the reasons; at this point the so-called floor effect is the most-favored explanation, referring to the deficient sensitivity of the UPDRS score in the lower range. The post hoc analysis can demonstrate that the analysis of the upper quartile UPDRS, and therefore removal of the floor effect, showed significance for both doses Citation[9].

According to clinical experience, a large percentage of the patients will also benefit from RAS with regard to vigilance, mood and quality of life. These observations were supported by a larger post-marketing observational study Citation[10]. The studies backed up not only the improvement of motor function, but also the appreciable impact on cognition and other non-motor disturbances Citation[8,11]. RAS also proved to be effective in elderly patients Citation[12].

Since there may be a delay of action in some patients, final conclusions should be postponed until after 4 weeks of treatment.

4. Clinical safety

RAS is easily tolerated, with less undesired effects compared with selegiline and equal to the levels of placebo. Elderly patients will also tolerate the agent well Citation[13]. Possible interactions with foodstuffs containing tyramine have been pointed out, but this is an apparently theoretical hazard only. A serotoninergic action might occur with RAS but is certainly rather unlikely. Caution is nevertheless advised when combining it with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs).

5. Disease-modifying effect of MAO-B inhibitors

This discussion, too, goes back > 20 years; the studies done at that time are no longer in keeping with today's standards, but they were trailblazing in the past and have not lost their significance Citation[14]. Disease-modifying effects have also been discussed for RAS and were endorsed by several studies. Contrary to amphetamine, aminoindane seems to be particularly important in this respect since it is supposed to have additional “neuroprotective” properties. Its hypothesized potential disease-modifying effect was corroborated in a clinical study that showed a more favorable course in patients that had been subjected to early treatment versus patients whose treatment had been delayed for 6 months. The ADAGIO study Citation[8] confirms a disease-modifying action for at least 1 mg/day arm. This had never been proven by another substance before. After ADAGIO Citation[8] had been published, there was a revival of discussion since the 2 mg arm missed the goal of treatment. This interpretation is nonetheless arbitrary, since the requirements of the study were met regarding the 1 mg arm, which is the approved dose. The fact that the double dose missed out on one of the therapeutic objectives has no contradiction per se. It is the guiding principle for the effect of medicinal treatment that doubling the dose must result in equal or better efficacy, but not in principle (e.g., U-shaped curve). The greatest available evidence of disease progression is currently attached to 1 mg RAS. Nevertheless, the post hoc analysis can demonstrate significant differences even in the 2 mg arm, if the floor effect was removed.

Since the PROUD study – an examination with the same design and pramipexole – turned out negative, the conclusion drawn from the ADAGIO study would seem even more positive.

6. Evidence-based medicine

We live in the era of evidence-based medicine (EBM) – with all its advantages and disadvantages. We ought to be aware, though, that EBM should not be used arbitrarily and at one's discretion might be appropriate. This implies that we should be willing to approve therapeutic procedures despite the lacking evidence, and despite what is suggested by the studies conducted. Inversely, it holds true that – in spite of the pressure imposed by costs – we must not is belittle obvious evidence.

Although we have got the same supply of data and thus evidence worldwide, the different national guidelines are greatly inhomogeneous. The value of MAO-B inhibitors is not uniform on the international scale. There are countries where MAO-B inhibitors are used as a matter of principle, and in other countries this group of substances is scarcely applied. The two substances, RAS and selegiline, share a similar fate despite both of them being market leaders in some countries, such as RAS in Spain.

7. Which patient needs MAO-B inhibitors?

We might basically claim: Everyone who is going to benefit from it needs MAO-B inhibitors. However, this is not always that simple to maintain. If the indication is correct, when contraindications are ruled out and the objective of treatment is accomplished – the patient should be getting this substance as before. It should only be withdrawn or refrained from in the event of intolerances or inefficacy. If treatment with an MAO-B inhibitor fails to be adequately effective, the German guideline suggests maintaining this therapy and combining it with a more powerful dopaminergic agent. The choice between levodopa and/or dopamine agonist should be based upon the established and upheld criteria for initial monotherapy.

In the future – by decoding the gene polymorphism – we might be able to clarify at the early stage whether or not the medication is truly indicated and helpful, and its therapeutic effect ensured.

8. When should MAO-B inhibitors be used?

In monotherapy, MAO-B inhibitors have a symptomatic effect and, when used in combination, they can improve levodopa therapy as well as therapy with dopamine agonists Citation[1-3,7]. The indication may thus be given at any stage of the illness. If a disease-modifying effect is assumed, treatment with MAO-B inhibitors should be introduced and only be withdrawn in cases of intolerance or contraindication.

Selegiline and RAS impact positively on motor symptoms, with RAS being slightly superior Citation[15]. RAS has less side effects and interactions, and is explicitly supported by more valid data. This also applies to the question of possible disease modification.

9. Outlook

In summary, MAO-B inhibitors, especially RAS, have a relevant place in the treatment of Parkinson's disease. New substances, such as safinamide, are being developed and the question of a disease-modifying action still remains to be settled.

Declaration of interest

WH Jost is a speaker and advisor for Teva Pharmaceutical Industries.

Notes

Bibliography

- Parkinson Study Group. A controlled trial of rasagiline in early Parkinson disease. The TEMPO study. Arch Neurol 2002;59:1937-43

- Parkinson Study Group. A randomized placebo-controlled trial of rasagiline in levodopa-treated patients with Parkinson disease and motor fluctuations. The PRESTO study. Arch Neurol 2005;62:241-8

- Rascol O, Brooks DJ, Melamed E, et al. Rasagiline as an adjunct to levodopa in patients with Parkinson's disease and motor fluctuations (LARGO, Lasting effect in Adjunct therapy with Rasagiline Given Once daily, study): a randomised, double-blind, parallel-group trial. Lancet 2005;365:947-54

- Youdim MBH, Gross A, Finberg JP. Rasagiline [N-propargyl-1R (+)-aminoindan], a selective and potent inhibitor of mitochondrial monoamine oxidase B. Br J Pharmacol 2001;132:500-6

- Chen JJ, Swope DM, Dashtipour K. Comprehensive review of rasagiline, a second-generation monoamine oxidase inhibitor, for the treatment of Parkinson's disease. Clin Therapeutics 2007;9:1825-49

- Lew MF, Hauser RA, Hurtig HI, et al. Long-term efficacy of rasagiline in early Parkinson‘s disease. Int J Neurosci 2010;120:404-8

- Hauser R, Silver D, Choudhry A, Isaacson S. A placebo controlled, randomized, double-blind study to assess the safety and clinical benefit of rasagiline as an add-on therapy to dopamine agonist monotherapy in early Parkinson's disease (PD): The ANDANTE study. Poster P006 Presented at the 65th AAN-Meeting; 16-23 March 2013; San Diego

- Olanow CW, Rascol O, Hauser R, et al. A double-blind, delayed-start trial of rasagiline in Parkinson's disease. N Engl J Med 2009;361:1268-78

- Rascol O, Fitzer-Attas CJ, Hauser R, et al. A double-blind, delayed-start trial of rasagiline in Parkinson's disease (the ADAGIO study): prespecified and post-hoc analyses of the need for additional therapies, changes in UPDRS scores, and non-motor outcomes. Lancet Neurol 2011;10:415-23

- Jost WH, Klasser M, Reichmann H. Rasagilin im klinischen Alltag. Fortschr Neurol Psych 2008;76:594-9

- Hanagasi HA, Gurvit H, Unsalan P, et al. The effects of rasagiline on cognitive deficits in Parkinson's disease patients without dementia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter study. Mov Disord 2011;26:1851-8

- Tolosa E, Stern MB. Efficacy, safety and tolerability of rasagiline as adjunctive therapy in elderly patients with Parkinson's disease. Eur J Neurol 2012;19:258-64

- Goetz CG, Schwid SR, Eberly SW, et al. Safety of rasagiline in elderly patients with Parkinson disease. Neurology 2006;66:1427-9

- Parkinson Study Group. DATATOP: a multicenter controlled trial in early Parkinson's disease. Arch Neurol 1989;46:1052-60

- Jost WH, Friede M, Schnitker J. Indirect meta-analysis of randomised placebo-controlled clinical trials on rasagiline and selegiline in the symptomatic treatment of Parkinson's disease. Basal Ganglia 2012;2:S17-26