Abstract

3-Hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase inhibitors (statins) have been proved highly effective treatments for primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular diseases. Despite widespread and long-term use of statins, there is still a debate concerning their association with cancer at various sites, including breast. As of today, the accumulated epidemiological evidence does not support the hypothesis that statin use affects the risk of developing breast cancer when taken at low doses for managing hypercholesterolemia. However, current evidence cannot exclude an increased risk of breast cancer with statin use in subsets of individuals, for example, the elderly. On the other hand, some studies show that statins might be useful to prevent recurrence and improve survival in patients already suffering from certain breast cancer types. They could also be combined with certain anticancer drugs and potentiate their effects, ameliorate their side effects or prevent the development of resistance. Further research is warranted to clarify these issues.

1. Introduction

3-Hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A (HMG-CoA) reductase inhibitors (statins) comprise a therapeutic class of agents that reduce plasma cholesterol levels by inhibiting hepatic HMG-CoA reductase, the rate-controlling enzyme in cholesterol synthesis. Having been proved highly effective treatments for primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular diseases, statins are currently among the most commonly prescribed medications, worldwide.

Despite widespread and long-term use of statins, there is still a debate concerning their association with cancer at various sites, including breast. Initially, one randomized controlled trial (RCT) raised concerns regarding their safety, reporting that breast cancer occurred in a significantly higher number of women treated with statin Citation[1], but subsequently, a large body of laboratory data suggested that statins might even have chemopreventive potential against breast cancer Citation[2].

In this issue of Expert Opinion on Drug Safety, Yang et al. Citation[3] carefully examine the association between statin use and breast cancer risk in a population-based case-control study in Taiwan, which included 565 breast cancer cases and 2260 matched controls. They did not find evidence to support either a beneficial or a harmful association between statin use and breast cancer risk. To obtain a coherent picture of the evidence, we sought to systematically retrieve, appropriately synthesize and discuss the existing evidence on the subject.

2. Current evidence

RCTs are thought to produce the most scientifically rigorous data among all study designs. We retrieved the existing randomized data by searching Medline database. Studies were considered eligible if they were RCTs evaluating a statin therapy compared with placebo or no treatment, had no other intervention difference between the experimental and the control group, enrolled at least 500 women, had a minimum duration of 2 years and reported the incidence of breast cancer in both trial arms.

To synthesize the evidence, we followed a methodological approach previously described Citation[4]. Risk ratios (RRs) and 95% CIs were calculated for each RCT by reconstructing contingency tables based on the intention-to-treat principle. Summary effect estimates were calculated using both the fixed- and the random-effects models. Selective outcome reporting bias was assessed using the Begg and Mazumdar adjusted rank correlation test and the Egger regression asymmetry test. Homogeneity was evaluated by the Cochran's Q test and quantified by the I-squared metric.

We identified and analyzed nine eligible RCTs of statins for cardiovascular outcomes () Citation[1,5-12]. They reported site-specific cancer outcomes, including breast cancer, as secondary/safety end points. Approximately 28,600 women (among 85,000 participants) were randomized in these 9 trials, with an average follow-up of 4.3 years. A total experience of over 120,000 person-years was reached. Meta-analysis of all nine trials showed no evidence for an association between statin use and breast cancer risk. The overall incidence of breast cancer was 1.14% in the treatment group (163 incident cases of breast cancer) and 1.11% in the control group (160 incident cases).

Table 1. Randomized controlled trials included in the meta-analysis.

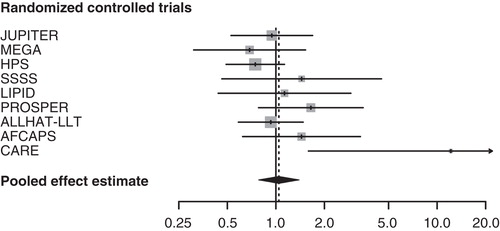

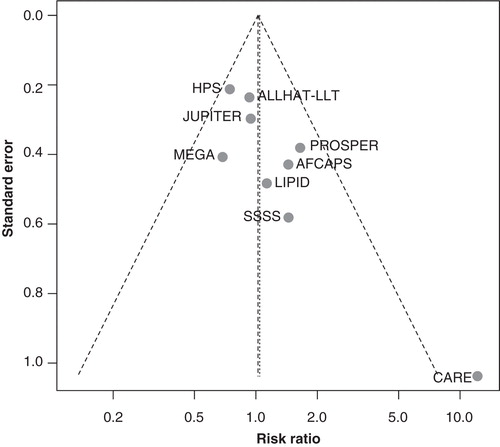

The association of statin use with breast cancer was neutral either assuming a fixed-effects (RR: 1.02, 95% CI: 0.82, 1.27) or a random-effects model (RR: 1.04, 95% CI: 0.78, 1.39) (). graphs the RRs and 95% CIs from the individual trials and the pooled results. The relevant tests indicated no important heterogeneity across the studies. On the other hand, we found evidence of selective outcome reporting. The funnel plot did not have the expected symmetrical shape (), and the relevant statistical tests were significant (). When the analysis was restricted to large trials Citation[6,7,10,11] or to trials that evaluated statin therapy compared with placebo Citation[1,5,7-10,12], the results did not substantially change (). Similarly, after stratifying the data in two subgroups according to lipophilicity of statins, we did not find any association between lipophilic and lipophobic statins and the risk of breast cancer. Last, to explore whether the results were dominated by a single study, we performed a ‘leave-one-out' sensitivity analysis, removing one study at a time. This approach confirmed the stability of our results.

Figure 1. Forest plot: results from individual RCTs and meta-analysis. The RR and 95% CI for each study are displayed on a logarithmic scale. Pooled estimate is from a random-effects model.

Figure 2. Funnel plot of observed risk ratio against standard error (as a surrogate of study size) for all studies analyzed.

Table 2. Meta-analysis results.

The RCT design is considered the gold standard for assessing drugs. However, it may be insufficiently powered to detect rare but serious adverse effects in the risk of common disease outcomes, such as breast cancer, that can have a major population impact in absolute terms. Moreover, to date, no sufficient data are available to define the long-term effects of prolonged statin use up to 10 years and beyond.

The observational data and the randomized data are consistent. The most recent comprehensive meta-analysis of 24 observational (13 cohort and 11 case-control) studies, involving > 2.4 million subjects followed for 2 – 15 years, found no evidence for an association between statin use (and long-term statin use) and breast cancer risk Citation[13]. This neutral result was evident for both lipophilic and lipophobic statins.

3. Conclusion

The accumulated epidemiological evidence does not support the hypothesis that statin use affects the risk of developing breast cancer when taken at low doses for managing hypercholesterolemia. However, current evidence cannot exclude an altered breast cancer risk with statin use for different cancer types, or in subsets of individuals, for example, the elderly Citation[14].

4. Expert opinion

The sum of the current evidence, to which the study by Yang et al. Citation[3] is a useful addition, practically lays to rest the hypothesis that statins might be useful for primary chemoprevention of breast cancer in the general population. Ideally, such a hypothesis should be evaluated in a randomized trial of sufficient power and length of follow-up, and with cancer as a primary end point; however, we believe that such a trial would probably be superfluous given the current evidence, and most importantly, it would be very hard to properly implement in practice.

Nevertheless, this is not the end of the road for statins and breast cancer; the evidence from preclinical studies, and some clinical studies, is just too compelling to ignore. For example, lipophilic statins have been found to be cytotoxic against breast adenocarcinoma cells, induce cell-cycle arrest and inhibit signaling pathways involved in invasiveness and metastasis in breast cancer cell lines, and potentiate the effects of antineoplastic agents such as cisplatin, doxorubicin and epirubicin Citation[15]. Rather a new, more targeted approach is warranted for future studies. Such an approach should recognize that different statins can have variable effects on different cancer types.

Estrogen receptor-negative breast tumors with high HMG-CoA reductase expression may be most affected by statin compounds, particularly lipophilic ones. Thus, statins might be useful in secondary chemoprevention, to prevent recurrence and improve survival in patients already suffering from certain breast cancer types. Already some observational studies have shown a reduced risk of recurrence in breast cancer patients using statins Citation[16,17], while others have not Citation[18].

Statins can also be combined with certain anticancer drugs and potentiate their effects, ameliorate their side effects or prevent the development of resistance Citation[15]. Upcoming clinical studies should therefore focus on the role of particular statins in the treatment and secondary chemoprevention of breast cancer. We expect to see more such studies performed in the future, relating any statin effect to particular biological characteristics of the tumor, biomarkers and so on. In addition, pharmacogenomics may eventually identify population subgroups at higher risk of certain cancer types, who may benefit from statins even when taken as primary chemoprevention.

In conclusion, the accumulated evidence clearly shows that statins are not a ‘magic bullet' for breast cancer. It is still quite possible, however, that statins may have a role to play in cancer prevention and treatment.

Declaration of interest

The authors state no conflict of interest and have received no payment in preparation of this manuscript.

Notes

Bibliography

- Sacks FM, Pfeffer MA, Moye LA, et al. The effect of pravastatin on coronary events after myocardial infarction in patients with average cholesterol levels. Cholesterol and recurrent events trial INVESTIGATORS. N Engl J Med 1996;335:1001-9

- Bonovas S, Filioussi K, Tsavaris N, Sitaras NM. Use of statins and breast cancer: a meta-analysis of seven randomized clinical trials and nine observational studies. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:8606-12

- Yang C, Chan TF, Wu CH, Lin CL. Statin use and the risk of breast cancer: a population-based case–control study. Expert Opin Drug Saf 2014;13(3):287-93

- Nikolopoulos GK, Bagos PG, Bonovas S. Developing the evidence base for cancer chemoprevention: use of meta-analysis. Curr Drug Targets 2011;12:1989-97

- Hsia J, MacFadyen JG, Monyak J, Ridker PM. Cardiovascular event reduction and adverse events among subjects attaining low-density lipoprotein cholesterol <50 mg/dl with rosuvastatin. The JUPITER trial (justification for the use of statins in prevention: an intervention trial evaluating rosuvastatin). J Am Coll Cardiol 2011;57:1666-75

- Nakamura H, Arakawa K, Itakura H, et al. Primary prevention of cardiovascular disease with pravastatin in japan (MEGA study): a prospective randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2006;368:1155-63

- Heart Protection Study Collaborative Group. The effects of cholesterol lowering with simvastatin on cause-specific mortality and on cancer incidence in 20,536 high-risk people: a randomised placebo-controlled trial [ISRCTN48489393]. BMC Med 2005;3:6

- Strandberg TE, Pyörälä K, Cook TJ, et al. Mortality and incidence of cancer during 10-year follow-up of the scandinavian simvastatin survival study (4S). Lancet 2004;364:771-7

- Hague W, Forder P, Simes J, et al. Effect of pravastatin on cardiovascular events and mortality in 1516 women with coronary heart disease: results from the long-term intervention with pravastatin in ischemic disease (LIPID) study. Am Heart J 2003;145:643-51

- Shepherd J, Blauw GJ, Murphy MB, et al. Prospective study of pravastatin in the elderly at risk. Pravastatin in elderly individuals at risk of vascular disease (PROSPER): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2002;360:1623-30

- ALLHAT Officers and Coordinators for the ALLHAT Collaborative Research Group. The antihypertensive and lipid-lowering treatment to prevent heart attack trial. Major outcomes in moderately hypercholesterolemic, hypertensive patients randomized to pravastatin vs usual care: the antihypertensive and lipid-lowering treatment to prevent heart attack trial (ALLHAT-LLT). JAMA 2002;288:2998-3007

- Clearfield M, Downs JR, Weis S, et al. Air force/texas coronary atherosclerosis prevention study (AFCAPS/TexCAPS): efficacy and tolerability of long-term treatment with lovastatin in women. J Womens Health Gend Based Med 2001;10:971-81

- Undela K, Srikanth V, Bansal D. Statin use and risk of breast cancer: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2012;135:261-9

- Bonovas S, Sitaras NM. Does pravastatin promote cancer in elderly patients? A meta-analysis. CMAJ 2007;176:649-54

- Osmak M. Statins and cancer: current and future prospects. Cancer Lett 2012;324:1-12

- Ahern TP, Pedersen L, Tarp M, et al. Statin prescriptions and breast cancer recurrence risk: a danish nationwide prospective cohort study. J Natl Cancer Inst 2011;103:1461-8

- Chae YK, Valsecchi ME, Kim J, et al. Reduced risk of breast cancer recurrence in patients using ACE inhibitors, ARBs, and/or statins. Cancer Invest 2011;29:585-93

- Nickels S, Vrieling A, Seibold P, et al. Mortality and recurrence risk in relation to the use of lipid-lowering drugs in a prospective breast cancer patient cohort. PLoS One 2013;8:e75088