Duchenne muscular dystrophy is a rare, life-threatening neuromuscular disorder that affects approximately 1 in 3802 – 6291 live male births worldwide Citation[1]. The disorder is caused by frame-shifting mutations in the dystrophin gene that prevent the expression of functional dystrophin protein, an important structural component of muscle tissue. Duchenne is inherited in an X-linked manner and de novo mutations may occur in people without a known family history of the disease. While both sexes can carry the mutation, females rarely exhibit signs of the disease. A small percentage of female carriers may exhibit a range of muscle symptoms from the full Duchenne phenotype to mild symptoms of muscle weakness Citation[2].

Diagnosis usually occurs between 3 and 5 years of age when differences in motor function become apparent. Families who receive this diagnosis hear words such as ‘progressive’, ‘debilitating’, ‘life-limiting’, ‘fatal’, and these words surround their daily lives. It is as if the families are on a carousel, each one in motion on a different trajectory, a whirl of emotions of hope and despair, each family reaching for the brass ring. The carousel menagerie includes dark horses; worries about the well-defined trajectory with its loss of ambulation, loss of arm function, loss of the ability to breathe; and a permanent proximity to the death of their child.

Duchenne is well characterized. The fundamental defect is a loss of the structural protein dystrophin. Today, thanks in no small measure to the MD-CARE Act legislation passed in 2001 Citation[3], the research community is galvanized, investing over $200 million dollars in Duchenne and resulting in a robust pipeline of opportunities and potential treatments. Strategies to mitigate Duchenne include targeting the fundamental genetic defect and the downstream cascade of events to include inflammation and fibrosis. Additional targets focus on improving muscle mass and blood flow to muscle. The potential treatments that target the dystrophin restoration – antisense oligonucleotides (exon skipping) Citation[4] and stop codon read-through (nonsense suppression) -- feel like the shiniest brass ring of all. Because to some of the families waiting, antisense oligonucleotides and stop codon read-through appear to be within reach. We believe these strategies will change the trajectory, the predicted progression of Duchenne to something less severe, dramatically slowing or halting progression, preventing the series of losses so frighteningly well described at diagnosis.

How close are we to a cure? To mimic the words of President Clinton, it depends on your definition of the word ‘cure’. For parents of children diagnosed with Duchenne, the quest for a cure begins at diagnosis and involves identifying the ‘right’ clinic, the most experienced physicians, having the ‘right’ mutation for the most promising clinical trials, fitting the inclusion criteria and gaining acceptance into the clinical study, being on the active compound rather than the placebo and seeing an effect, completing the study and learning that the compound indeed had a statistical effect on the population studied. In a pilot study to quantify caregiver preferences for the benefits and risks of emerging therapies, parents were found to be willing to accept a serious risk when balanced by an effective, although noncurative treatment, even absent improvement in lifespan. Caregivers attributed very high scores to stopping or slowing progression of muscle weakness Citation[5].

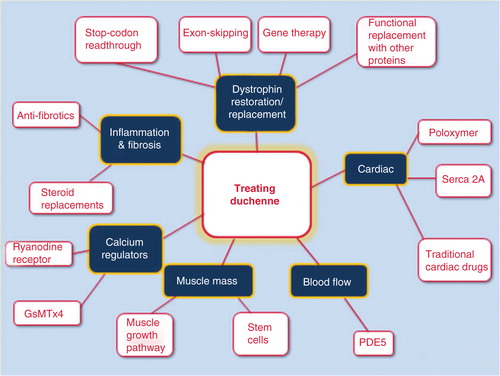

Extensive research into both the molecular basis and pathophysiology of Duchenne has paved the way not only for the development of strategies that aim to correct the primary defect, but also toward the identification of countless therapeutic targets with the potential to alleviate the downstream pathology. These include anti-inflammatories, antifibrotic, positive and negative regulators of muscle growth and drugs that improve blood flow to muscle. Families see these targets as opportunities to slow muscle degeneration, particularly when used in combination with drugs that target the primary defect, such as antisense oligonucleotides, nonsense suppression or utrophin upregulation ().

Figure 1. Pictoral diagram identifying current targets in drug development for Duchenne muscular dystrophy.

Families tend to define ‘cure’ in the context of their son and his progression.

I invited a number of parents to comment on the question, ‘When will Duchenne be cured?’ While I received a range of timelines, the thread of halting progression was woven throughout.

“In my mind a cure for DMD would prevent any loss of physical function allowing a person to do the same things as an unaffected peer as well as assure them (not ensure) that they have a similar predicted lifespan”.

“One definition of “a cure” would be a world in which Duchenne no longer occurs. I could envision a possibility of Duchenne prevention in a Star Trek-like future in which prospective parents could get some kind of anti-mutation vaccine. (In vitro with testing, which is possible today, would be another preventative technique). I could also envision a world in which genetic testing in utero was the norm, an in which a mother might take a medication to correct for an identified mutation”.

“My favorite definition of a cure for Duchenne is this scenario: A baby is born. He gets full genetic testing via heel prick. Duchenne is diagnosed within the first two weeks after birth. Parents are told that this is a chronic condition which requires a single daily pill. Regular home-town primary care provider prescribes the pill. Family gets pills refilled regularly at the local pharmacy for a reasonable and affordable price (covered by all insurances). Child takes his pill every day and leads a perfectly normal life with no Duchenne symptoms, no major side effects, regular life span, and so on. Family spends their medical energy worrying about serious conditions like influenza instead. Estimated time for arrival on this reality? Depending on funding stability, politics, and so on, do you think it could be done in 100 years?”

“We know more now than we did 10 years ago when we were diagnosed, but we also now have more questions than we had back then. It is like the more we learn, the less we know… What is clear is that there are many forms of imperfect dystrophin and some of them aren’t going to be useful. And dystrophin induced later in life is not the same as having it from birth”.

Each parent I asked had their own timeline and version for a cure. Some could feel it, see it on the horizon, referred to it as ‘soon’, in their son’s lifetime. Others believed this generation would not be cured, but they felt hopeful for a combination of personalized therapies that might serve to halt progression. All discussed the need to address the heart, knowing that the current pipeline of possibilities does not do so. Most asked questions about improving or stabilizing skeletal muscle function. They worried about adding burden to an essentially untreated heart.

But we all agree a cure would have to include getting off the carousel, making the dark horses no longer a threat. The components of a cure would have to include a combination of therapies and end progression at whatever stage. Therapies need to be accessible for all individuals, no matter where they live. Treatments need to be affordable and locally delivered. A cure would mean that families would be relieved of the burden of illness and the worry of burying their child before he/she has had the opportunity to live.

Declaration of interest

The author has no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank the parents who provided comments: Mindy Cameron, Ivy Scherbarth, Brian Denger and many others who offered opinions and comments.

Notes

Bibliography

- Mah JK, Korngut L, Dykeman J, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis on the epidemiology of Duchenne and Becker muscular dystrophy. Neuromuscul Disord 2014;24(6):482-91

- Giliberto F, Radic CP, Luce L, et al. Symptomatic female carriers of Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD): genetic and clinical characterization. J Neurol Sci 2014;336(1-2):36-41

- HR 717 (107th): MD-CARE Act. 2001. Available from: www.govtrack.us/congress/bills/107/hr717 [Last accessed 20 August 2014]

- ‘Exon skipping for the therapy of Duchenne muscular dystrophy’ Interview with Dr Annemieke Aartsma-Rus, Leiden University Medical Center, Netherlands. Available from: www.treat-nmd.eu/downloads/file/dmd/reports/Interview_Dr_%20Annemieke_Aartsma_Rus_EN.pdf [Last accessed 1 September 2014]

- Peay HL, Hollin I, Fischer R, et al. A community-engaged approach to quantifying caregiver preferences for the benefits and risks of emerging therapies for duchenne muscular dystrophy. Clin Ther 2014;36(5):624-37