Abstract

Background: Some patients with partial onset seizures are drug-resistant and may benefit from adjunctive therapy. This study evaluated monotherapy/sequential monotherapy versus adjunctive therapy on use/costs. Methods: Retrospective analysis using commercial/Medicare database (1 January 2007 to 31 December 2009). Patients with ≥2 diagnoses for partial onset seizures who received ≥2 prescriptions of the same antiepileptic drug were included. Outcomes assessed in the 12-month follow-up period were hospitalizations, ER visits, outpatient visits and prescription costs for patients who received monotherapy but switched to adjunctive. Results: 1353 patients met criteria. After patients transitioned to adjunctive therapy, the average monthly percentage of patients with a hospitalization decreased from 5.3 to 3.0% (p < 0.0001). Similar results occurred with epilepsy-related hospitalizations (4.0 vs 1.7%, p < 0.0001). Adjusted costs decreased significantly (US$4205 vs 2944/month, p < 0.0001). Adjusted epilepsy-related costs decreased from US$1601 to 909/month (p < 0.0001). Conclusion: Adjunctive therapy in potentially drug-resistant patients with partial onset seizures can lead to reduced healthcare use and costs.

Background

Epilepsy is a disorder affecting 50 million people worldwide; approximately 2 million of them are Americans Citation[1,2]. A specific class of seizures, partial onset seizures (POS), affects localized or focal regions of the brain accounting for approximately 60% of patients with epilepsy Citation[3,4]. The primary goal in the treatment of epilepsy, regardless of the type of seizures, is freedom from seizures with as few side effects from medications as possible Citation[5], with the typical standard of therapy consisting of the use of antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) Citation[6]. Therapy is usually initiated with a single AED Citation[7]; however, even when medications are taken properly, up to 30% of patients with POS still suffer from inadequate seizure control Citation[8–10]. Oftentimes, these patients may not respond adequately to the AED and may be considered drug-resistant. The International League Against Epilepsy defines drug-resistant epilepsy as failure of adequate trials of two tolerated and appropriately chosen and used AED schedules, either in monotherapy or in combination Citation[11]. For patients who experience inadequate seizure control, physicians are faced with two treatment options: sequential monotherapy, whereby patients are switched to another single AED, or adjunctive therapy, when physicians add additional AED medications.

The use of adjunctive therapy has been debated over the years. With the use of first-generation AEDs, adjunctive therapy had the propensity to increase problematic side effects in patients, thus making sequential monotherapy the preferred option for patients not well controlled. However, for patients with potential drug-resistant epilepsy, the likelihood of benefiting from subsequent trials of monotherapy agents may be small, and initiating adjunctive therapy earlier in the treatment plan may improve outcomes Citation[12]. The advent of newer AEDs has led to the development of medications with differing mechanisms of actions and improved side-effect profiles. In theory, combining agents may, therefore, present fewer difficulties than were associated with older treatment regimens and is clinically a viable means to improving seizure control in drug-resistant patients.

Improvement in clinical outcomes can also lead to improved economic outcomes. The economic burden of POS is substantial, predominately because of the fact that this group represents the largest number of patients with epilepsy. It has been well established that patients with refractory POS (defined as ≥3 AEDs in other studies) incur higher resource use and/or costs Citation[13–18]. In a study comparing patients with POS to patients with refractory POS, average annual costs for refractory patients were significantly higher than non-refractory patients (US$33,613 vs US$19,085) Citation[16].

The clinical and economic burden of POS has been quantified, but the clinical and economic evidence to support the use of adjunctive therapy is still limited, furthering the need to evaluate treatment outcomes of adjunctive therapy for the treatment of potentially drug-resistant patients in a real-world clinical practice. Although it was not possible to determine clinically whether the patients in this study were drug-resistant or not, based on the definition set forth by International League Against Epilepsy for drug-resistant epilepsy, it was assumed that at least some portion of the patients switching from monotherapy to adjunctive therapy were likely drug-resistant. For our purposes, we termed these patients ‘potentially drug-resistant’. The methodology and approach for patient selection for this study were similar to other current studies evaluating adjunctive therapy Citation[19]. The purpose of this study was to determine the effect of monotherapy/sequential monotherapy versus adjunctive therapy on healthcare resource use and costs for patients with potentially drug-resistant POS.

Methods

A retrospective claims analysis was conducted using the Truven Health MarketScan® Commercial Claims and Encounters (Commercial) Database covering the time period from 1 January 2007 to 31 December 2009. This database contains the healthcare experience of approximately 32 million privately insured individuals and their dependents covered under a variety of health plans. Detailed enrollment, use, costs and outcomes data are available for services performed in inpatient and outpatient settings, including medical and pharmacy claims. All database records are de-identified and fully compliant with US patient confidentiality requirements.

Patients with at least two diagnosis codes for POS (ICD-9 CM codes 345.4 and 345.5 for POS; 345.9 for unspecific epilepsy; and 790.39 for other convulsions as it is commonly used for POS seizures) who received ≥2 prescriptions for at least one AED were included. The first prescription date was considered to be the index date. Patients were required to be continuously eligible in the 6-month pre-period and the 12-month post-period from the index date. As a result of these criteria, patients were likely newly diagnosed as they had not received an AED in the 6 months prior to the index date. Patients who were diagnosed with bipolar disorder, migraines or headache were excluded.

Four possible treatment cohorts were established based on AED prescribing patterns during the study period: patients who received monotherapy only (one/same agent throughout the follow-up period); patients who received monotherapy (one agent or sequential monotherapy) but were switched to adjunctive therapy (received more than one AED, with AED therapy overlapping >60 days); patients who received adjunctive therapy from the beginning (received more than one AED and overlapped >60 days within the first 90 days of the index date); and patients who received sequential monotherapy (received more than one AED but different AEDs only overlapped once or for ≤60 days). For the study objective, the analysis focused on the patient cohort who changed from monotherapy to adjunctive therapy, comparing economic outcomes between the monotherapy phase and the adjunctive therapy phase.

Baseline demographics included age, gender and Charlson Comorbidity Index score. The most commonly prescribed AEDs were captured and treatment duration was measured as the average number of days on therapy. To determine the effects of the different treatment regimens, outcomes were assessed in the form of all-cause hospitalizations, emergency room (ER) visits, outpatient visits and prescription use and costs. Epilepsy-related use and costs were also evaluated, defined as a medical service with a primary or secondary diagnosis of epilepsy. Average monthly costs were assessed for each medical use category to compare monotherapy/sequential monotherapy to adjunctive therapy. For this analysis, costs are representative of the amount paid for the service or medication. A subgroup analysis was also conducted by the number of AEDs received as monotherapy/sequential monotherapy to evaluate whether treatment outcomes may be affected by the number of AEDs as monotherapy prior to adjunctive therapy.

Descriptive statistics were calculated for continuous and categorical variables at baseline for the study patients. For continuous variables, means (standard deviations) and medians were generated. For categorical variables, percentages were reported. Within-subject differences were tested using paired t-tests or non-parametric Wilcoxon signed-rank tests for continuous data, and McNemar tests for categorical variables. Multivariate analysis was used for the cost component and included mixed regression models on the repeated measure analysis after adjusting for patient demographics (age, gender, CCI and number of previous ICD-9 diagnosis codes). To ensure the appropriateness of the 60-day overlap for cohort classification, a 90-day overlap window was also used as sensitivity analysis to address concerns that some patients may have required longer time to switch therapies.

Results

Study population

A total of 15,041 patients were identified as patients with POS meeting initial inclusion criteria. The study population consisted of 10,400 patients (69.1%) in the monotherapy-only cohort, 1353 patients (9%) in the monotherapy to adjunctive therapy cohort, 1125 patients (7.5%) in the adjunctive therapy from initiation cohort and 2163 (14.4%) in the serial monotherapy cohort. The mean age of the study population ranged from 47 to 51 years, depending on the treatment cohort, with less than half of patients being male (range 41–48% depending on treatment cohort). Baseline characteristics for all cohorts are provided in . All cohorts were included in this table for informational purposes.

Table 1. Baseline patient characteristics for all cohorts.

Treatment characteristics

In the monotherapy to adjunctive therapy cohort, 48.7% received one AED during the monotherapy phase, 44.4% received two AEDs and 6.8% received three or more AEDs before moving to adjunctive therapy. The overall average duration of the monotherapy phase was approximately 269 days (median 239 days). Levetiracetam was the most commonly prescribed agent during the monotherapy phase of treatment for this cohort with 29.4% of patients receiving it. For the adjunctive therapy phase, levetiracetam, regardless of dosage form, was most often used in combination with phenytoin or valproic acid. Additional information regarding AED therapies for the monotherapy to adjunctive therapy cohort is provided in .

Table 2. Most commonly prescribed antiepileptic drugs in the monotherapy to adjunctive therapy cohort.

Resource use & costs

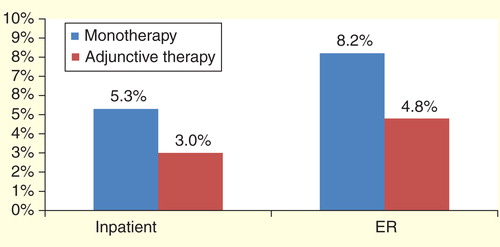

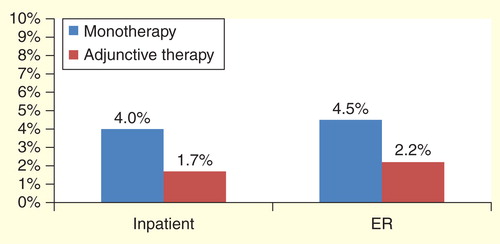

Once patients in the monotherapy to adjunctive therapy cohort transitioned from the monotherapy phase to the adjunctive therapy phase, the average monthly percentage of patients having a hospitalization for any reason (all-cause) decreased significantly from 5.3 to 3.0% (p < 0.0001). Similarly, ER visits decreased from 8.2 to 4.8% (p < 0.0001). This trend also occurred with epilepsy-related hospitalizations (4.0 vs 1.7%, p < 0.0001) and ER visits (4.5 vs 2.2%, p < 0.0001). Results are shown in .

Figure 1. Average monthly percentage of patients with an impatient hospitalization or emergency room visit for monotherapy versus adjunctive therapy phase (all-cause)*.

Figure 2. Average monthly percentage of patients with an impatient hospitalization or emergency room visit for monotherapy versus adjunctive therapy phase (seizure-related)*.

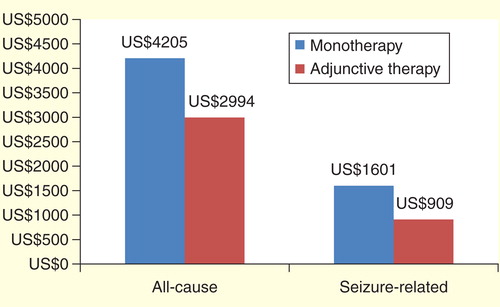

Congruent with the use results, overall healthcare costs decreased significantly for patients in the monotherapy to adjunctive treatment cohort after patients transitioned over to the adjunctive phase (average monthly cost US$4147 vs US$2886, p < 0.0001). When costs were adjusted for patient demographics, costs were US$4205 in the monotherapy phase and US$2994 in the adjunctive phase (p < 0.0001, ). Pharmacy epilepsy-related costs increased when patients in the monotherapy transitioned to the adjunctive therapy phase from US$189 per month to US$194 per month, but this increase was not significant (p = 0.2082). Despite the slight increase in pharmacy costs for this treatment cohort, total epilepsy-related monthly costs decreased from US$1577 to US$885 per month after transitioning to the adjunctive therapy phase. When adjusted for patient demographics, epilepsy-related costs were US$1601 for the monotherapy phase and US$909 for the adjunctive phase (p < 0.0001, ). All unadjusted costs are reported in .

Figure 3. Adjusted all-cause and seizure-related costs for monotherapy versus adjunctive therapy phase*.

Table 3. Unadjusted average monthly costs for monotherapy versus adjunctive therapy.

Healthcare costs by number of AEDs (1, 2 or 3 AEDs) as monotherapy prior to adjunctive therapy did not show significant difference . Sensitivity analysis using a 90-day overlap versus a 60-day overlap resulted in an approximately 10% decrease in sample size for the monotherapy to adjunctive therapy group (n = 1353 for 60 days vs n = 1207 for 90 days). However, results were similar and maintained directionality and significance.

Table 4. Change in healthcare costs by number of antiepileptic drugs received as monotherapy.

Discussion

When examining the history behind the monotherapy versus adjunctive therapy debate, it is important to consider the history of AEDs and their pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamics properties. The concept of sequential monotherapy began in the 1970s Citation[20,21]. Because of the agents available on the market at the time, when patients were switched to adjunctive therapy from monotherapy, only a relatively small percentage experienced a reduction in seizures (11–13%) and most had an increase in side effects Citation[22]. These trends began to change with the advent of newer AEDs in the 1990s. Prior to this time, sodium channel blocking agents were the mainstay of therapy, resulting in an amplification of side effects when drugs with the same mechanism of action were combined. Newer agents provide novel mechanisms of action, which result in the prospect of additive efficacy. These agents also offer less pharmacokinetic interactions and exhibit fewer side effects when combined Citation[23,24]. Consequently, recent literature suggested that the concept of adjunctive therapy should be revisited Citation[7,23,24]. Faught et al. concluded that adjunctive therapy should not be overlooked. His argument is that second or third monotherapy treatment sequences should be reconsidered because early polytherapy is often effective and well tolerated with the newer AEDs available Citation[7].

To date, limited clinical evidence exists in the comparison between monotherapy and adjunctive therapy. Deckers et al. conducted a double-blind randomized study that evaluated the carbamazepine alone versus carbamazepine and valproate in combination. There were 130 patients with tonic-clonic and partial seizures that participated in the study, with neurotoxicity serving as the primary outcome measure. Results from the study demonstrated no statistical differences in the reduction of seizure frequencies, overall neurotoxicity or in overall systemic toxicity. Adverse effects differed between the two groups of patients, and fewer patients receiving adjunctive therapy (polytherapy) withdrew because of adverse effects although the difference was not significant. Although the study demonstrated adjunctive therapy is potentially more tolerable, the trial was powered to detect differences in neurotoxicity, and not designed (powered) to evaluate differences in systemic toxicity or efficacy Citation[25]. Beghi et al. conducted a multicenter, parallel-group, open-label study in patients with cryptogenic or symptomatic partial epilepsy who were not controlled after single or sequential AED monotherapy. Patients were randomized to receive monotherapy with an alternative AED or adjunctive therapy with a second AED, with drug and dose determined by the physician’s best judgment. Outcomes measured were the proportion of patients continuing on the assigned treatment, proportion of patients seizure-free after achieving the targeted dose and adverse effect rates. There were 157 patients who participated in the study. More patients receiving adjunctive therapy continued the assigned treatment strategy, but the difference was not significant (65 vs 55%, p = 0.74). The probability of remaining seizure free was higher for the adjunctive group (16 vs 14%, p = 0.74), and similar adverse effects were noted between the groups. The authors did note, however, that power was also an issue for this study Citation[26].

Results from our study using real-world data indicate that patients who initially received monotherapy and transitioned to adjunctive therapy experienced significant decreases in resource use and costs, indicating better treatment outcomes associated with adjunctive therapy in patients with potentially drug-resistant epilepsy. This information is not only important clinically but also valuable from economic perspective because patients with refractory epilepsy account for 79% of costs, although they represent only a fraction of the patients with epilepsy (∼25%) Citation[27].

Determining which combination of AEDs is optimal is an area that is not well defined. This may be attributable to the individual reactions to the agents by patients, formulary restrictions or other considerations. Regardless of the reason, data evaluating the agents are limited Citation[23]. An advantage to adding an agent with a different mechanism of action has the potential to create a combination with a more favorable side-effect profile. For example, levetiracetam, a synaptic release modulator, rarely causes ataxia, so using it with an agent such as phenytoin, a sodium channel blocker, is less likely to cause balance issues Citation[7]. Emerging data from animal experiments have also suggested that combining AEDs with differing mechanisms of actions has the potential to produce a synergistic anticonvulsant effect without the consequences of neurotoxicity Citation[28]. Furthermore, patients who receive drug combinations with differing mechanisms of action have a lower risk for hospitalization or emergency room visits Citation[19].

To date, little guidance or diagnostic tools are available for physicians and other healthcare providers with regards to early identification and treatment of refractory epilepsy. An ongoing long-term observational study, the Human Epilepsy Project, may help identify clinical characteristics and biomarkers that predict disease progression and treatment responses for patients with epilepsy Citation[29].

Limitations

Several limitations exist with this study that warrant mentioning, most notably that there was not a separate control group. Also, as the analysis was based on medical and pharmacy insurance claims, it is not possible to determine the onset and frequency of seizures, thus overall and epilepsy-related medical services, including hospitalizations and ER visits, were used as a surrogate for clinical outcome measures. Information on epilepsy severity is also not possible to capture although some general baseline characteristics are captured by the use of the Charlson Comorbidity Index. Because of the nature of the pharmacy claims, it is only possible to determine that a patient had a claim filed for a specific AED; no information is available regarding clinical implications, such as discontinuation rates because of side effects, effectiveness or costs. Furthermore, because the results are based on claims data alone, it is possible that some patients may have required more than our 60-day window to transition from one monotherapy to another, making it appear as though they were receiving adjunctive therapy. However, when the window was extended to 90 days, it did not affect the directionality or significance of the results. It is also possible that some patients may have been treated for seizure disorders in the past but were in remission during the 6-month pre-period. Literature suggests that seizure outcome worsens with the number of lifetime AEDs Citation[30,31]; however, our comparison among the number of agents received in the monotherapy phase of therapy showed no difference in cost comparisons for patients receiving 1, 2 or ≥3 agents as monotherapy. It is our assumption that this 6-month window was beneficial in helping capture newly diagnosed patients in an effort to gain a clearer picture of the outcomes by therapy cohort.

It should also be noted that there was a small cohort of patients who received adjunctive therapy (by our data analysis definition) as initial AED therapy. Because physicians do not often start adjunctive therapy on newly diagnosed patients, the cohort may represent patients who started with AED rescue therapy but switched to other AEDs for long-term use, or patients who were not newly diagnosed, but may have entered from another plan or had prior pharmacy benefits not captured in this particular database.

Finally, information that may contribute to a patient’s quality of life is not captured through insurance claims, yet is an important aspect in this patient population and may weigh heavily into the physician’s choice of therapy for individual patients.

Conclusion

Results of this study indicate that transitioning from monotherapy to adjunctive therapy in patients with potentially drug-resistant POS can lead to reduced overall and epilepsy-related healthcare use and costs. Identification of patients who may be candidates for adjunctive therapy has important implications for the patient as well as the payers. Real-world data surrounding the use and outcomes of adjunctive therapy are sparse, and further analyses are needed to help further define the benefits of appropriate adjunctive therapy.

Partial onset seizures account for approximately 60% of patients with epilepsy.

Even when medications are taken properly, up to 30% of patients with partial onset seizures still suffer from inadequate seizure control.

Adjunctive therapy is a viable option for patients who do not respond to monotherapy, but the clinical and economic evidence to support the use of adjunctive therapy is still limited.

Results from this study indicate that patients who were initiated on monotherapy and transitioned to adjunctive therapy incurred lower resource use and costs.

Transitioning from monotherapy to adjunctive therapy in potentially drug-resistant patients with partial onset seizures can lead to reduced overall and epilepsy-related healthcare use and costs.

Financial & competing interests disclosure

This work was funded by Eisai Inc. Z Wang, X Li and A Powers are all employees of Eisai Inc. Meg Franklin of Franklin Pharmaceutical Consulting LLC provided assistance with manuscript preparation. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

Notes

References

- World Health Organization. Epilepsy: fact sheet N999 October 2012. Available from: www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs999/en/ [Last accessed on 24 October 2014]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Targeting epilepsy: improving the lives of people with one of the nation’s most common neurological conditions. Chronic disease at a glance reports 2011. Available from: www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/resources/publications/aag/epilepsy.htm [Last accessed on 24 October 2014]

- Banerjee PN, Filippi D, Allen Hauser W. The descriptive epidemiology of epilepsy-a review. Epilepsy Res 2009;85:31-45

- Baulac M, Leppik E. Efficacy and safety of adjunctive zonisamide therapy for refractory partial seizures. Epilepsy Res 2007;75(2-3):75-83

- Ben-Menachem E. Medical management of refractory epilepsy- practical treatment with novel antiepileptic drugs. Epilepsia 2014;55(Suppl 1):3-8

- Simoens S. Pharmacoeconomics of anti-epileptic drugs as adjunctive therapy for refractory epilepsy. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res 2010;10:309-15

- Faught E. Should monotherapy for epilepsy be reconsidered? US Neurology 2009;5:59-62

- Kwan P, Brodie MJ. Early identification of refractory epilepsy. N Eng J Med 2000;342:314-19

- Kwan P, Brodie MJ. Epilepsy after the first drug fails: substitution or add-on? Seizure 2000;9:464-8

- Chung SS. Lacosamide: new adjunctive treatment option for partial-onset seizures. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2010;11:1595-602

- Kwan P, Arzimangolou A, et al. Definition of drug resistant epilepsy: consensus proposal by the ad hoc task force of the ILAE commission on therapeutic strategies. Epilepsia 2010;51:1069-77

- Ivanova JI, Birnbaum HG, Kidolezi Y, et al. Direct and indirect costs associated with epileptic partial onset seizures among the privately insured in the United States. Epilepsia 2010;51:838-44

- Ivanova JI, Birnbaum HG, Kidolezi Y, et al. Economic burden of epilepsy among the privately insured in the US. Pharmacoeconomics 2010;28:675-85

- Lee WC, Hoffmann MS, Arcona S, et al. A cost comparison of alternative regimens for treatment-refractory partial seizure disorder: an econometric analysis. Clin Ther 2005;27:1629-38

- Lee WC, Arcona S, Thomas SK, et al. Effect of comorbidities on medical care use and cost among refractory patients with partial seizure disorder. Epilepsy Behav 2005;7:123-6

- Chen S, Wu N, Boulanger L, Sacco P. Antiepileptic drug treatment patterns and economic burden of commercially-insured patients with refractory epilepsy with partial onset seizures in the United States. J Med Economics 2013;16:1-9

- Yoon D, Frick KD, Carr DA, et al. Economic impact of epilepsy in the United States. Epilepsia 2009;50:2186-91

- Cramer JA, Wang ZJ, Chang E, et al. Healthcare utilization and costs in children with stable and uncontrolled epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav 2014;32:135-41

- Margolis JM, Chu B, Wang ZJ, et al. Effectiveness of antiepileptic drug combination therapy for partial-onset seizures based on mechanisms of action. JAMA Neurol 2014;71:985-93

- Shorvon SD, Reynolds EH. Reduction in polypharmacy for epilepsy. Br Med J 1979;2:1023-5

- Schmidt D. Reduction of two-drug therapy in intractable epilepsy. Epilepsia 1983;24:368-76

- Schmidt D. Two antiepileptic drugs for intractable epilepsy with complex-partial seizures. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1982;45:1119-24

- French JA, Faught E. Rational polytherapy. Epilepsia 2009;50(Suppl 8):63-8

- St Louis E. Truly “rational” polytherapy: maximizing efficacy and minimizing drug interactions, drug load, and adverse effects. Current Neuropharmacol 2009;7:96-105

- Deckers CLP, Yechiel AH, Keyser A, et al. Monotherapy versus polytherapy for epilepsy: a multicenter double-blind randomized study. Epilepsia 2001;42:1387-94

- Beghi E, Gatti G, Tonini C, et al. Adjunctive therapy versus alternative monotherapy in patients with partial epilepsy failing on a single drug: a multicentre, randomised, pragmatic controlled trial. Epilepsy Res 2003;57:1-13

- Begley CE, Famulari M, Annegers JF, et al. The cost of epilepsy in the United States: an estimate from population-based clinical and survey data. Epilepsia 2000;41:342-51

- Lasoń W, Dudra-Jastrzębska M, Rejdak K, Czuczwar SJ. Basic mechanisms of antiepileptic drugs and their pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic interactions: an update. Pharmacol Rep 2011;63(2):271-92

- The human epilepsy project. Available from: http://humanepilepsyproject.org/ [Last accessed 15 September 2014]

- Schiller Y, Naijar Y. Quantifying the response to antiepileptic drugs: effect of past treatment history. Neurology 2008;70:54-65

- Shorvon SD, Goodridge DM. Longitudinal cohort studies of the prognosis of epilepsy: contribution of the National General Practice Study of Epilepsy and other studies. Brain 2013;11136:3497-510