Abstract

True cures in health care are rare but likely not for long. The high price tag that accompanies a cure along with its rapid uptake create challenges in the financing of cures by public and private payers. In the US, the disaggregated nature of health insurance system adds to this challenge as patients frequently churn across multiple health plans. This creates a ‘free-rider’ problem, where no one health plan has the incentive to invest in cure since the returns will be scattered over many health plans. Here, a new health currency is proposed as a generalized version of a social impact bond that has the potential to solve this free-rider problem, as it can be traded not only between public and private payers but also within the private sector. An ensuing debate as to whether and how to develop such a currency can serve the US health care system well.

There are growing concerns about the financing of technological breakthroughs in medicine that provide not just incremental health benefits, but substantial leaps in patients’ health in the form of cures. The introduction of Sovaldi by Gilead, which is shown to cure 80–95% of Hepatitis-C infections, highlights these issues Citation[1], but is not a unique case. US FDA approval of Harvoni, Citation[2], a first combination pill approved to treat chronic Hepatitis-C virus genotype one infection, and other targeted treatments in cancer and emerging health technologies like regenerative medicine and gene therapy indicates that the concerns of financing these technologies are real Citation[3]. The concerns are not only that these cures come, and rightfully so, with a high price tag, but they are likely to be adopted by a large patient population in a short amount of time. For example, a recent analysis shows that the potential cost to Medicare of covering Sovaldi alone is a 3–8% increase in federal Part D outlays and Part D premiums Citation[4]. Similar concerns are expressed for Medi-Cal, California’s Medicaid Program about financing stem-cell therapies Citation[5]. Payers need access to sufficient capital in order to finance such a sharp impact on their budgets. While the development of generic markets to bring down costs of a high price cure has been put forth as a solution Citation[6], these markets appropriately take time to develop in order to preserve the incentives for innovation for the original developer of the cure. In the meantime, payers and the patients bear the steep upfront costs of a cure while the benefits, in terms of longevity, quality of life, reduced health care costs and other economic benefits, are realized over a longer time period. This creates discrepancies in motifs for financing cure. Recent discussions have highlighted the need to develop credit markets that will be able to amortize the costs of financing a cure over a longer time period Citation[7,8].

I argue that while these new credit markets are necessary to finance cures, they are not enough to address the problem of underinvestment in cures because of the disaggregated, private-based health insurance system in the US. Philipson Citation[3] compares the financing of cure to the purchase of a house, whose value is realized over a long time period. He argues that credit markets similar to those in the housing sector should be able to smooth out the costs of paying for a cure over the patient’s lifetime. But Philipson also points out that such mechanisms will be less valuable within the private insurance markets due to the relatively frequent turnover of beneficiaries in those plans Citation[3]. In fact, the same concerns permeate the public insurance system in the US as they are being increasingly managed by private plans.

A solution to this problem can be found in the economic literature dealing with externalities in the efficient provision of a public good Citation[9]. In the US health care system, a cure can be conceptualized as a ‘non-excludable’ public good. That is, a cure is valued by all private and public payers, but no one payer can exclude the others from appropriating some of its value. Consequently, since no one payer can appropriate the full value of the cure, none may be willing to bear the full costs of the cure – a classic ‘free-rider problem’ Citation[5], which leads to the under-provision of cures and under-investment in innovation. While collective action and consensus are often put forward as a solution to a free-rider problem Citation[10], they may be subject to insurmountable transaction costs within the US health insurance system. Here, I propose a different solution that may lead to efficient provision of cures in the US – monetization of the public good, the trading of which can happen at a much lower transaction costs, much in line with the concept of social impact bonds but more general in its reach Citation[11].

Monetization of cures – HealthCoin?

In Philipson’s housing example, credit markets alone can solve the buyer’s financing problem since a house is an ‘excludable good’. If you do not want to sell the house, you benefit living in it over time and can exclude any other entity to enjoy it during that time. If you sell it, you stop getting the value of living in that house, but recover the forgone value through its selling price. This is not the case when a payer purchases a cure. Even if a payer access credit markets to finance the high costs of cures, it cannot exclude other payers to enjoy the benefits of cure if patients decide change insurance plans. Here, although the original payer is foregoing the subsequent value of cure for these patients, it is not getting anything in return for their upfront investment in the cure.

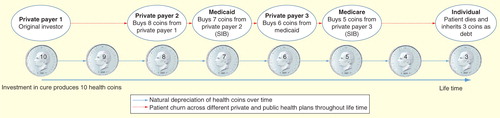

This problem can be solved by developing a tradable new currency that would convert the incremental consequences produced (but not the upfront costs incurred) by certain well-established cures to a common numeraire, such as health stock units, life-years equivalents or some other metric. Let’s call this currency HealthCoin. HealthCoins will depreciate over time (in line with depreciation of any capital stock) and could be traded with real dollars in the marketplace among private and public payers. Since Medicare is the largest public insurance system in the US and would often be the recipient of a substantial part of the value generated due to investment in cure in early life, it would be expected that the US government would back this currency with necessary assurances. Medicare or its managed care plans would also buy the present value of the HealthCoins as patients become eligible for Medicare, much in line with the spirit of social impact bonds that are being used across the world to pay for investments that produce returns to public sector Citation[12].

Figure 1. A stylized model illustrating how health coins could be traded across public and private payers thereby generating the incentives for efficient investments in developing and utilizing cures.

The valuation of HealthCoins for Medicare’s perspectives must go beyond just the health care costs perspectives since most cures would likely increase total health care costs rather decrease them due to the extension of life. Therefore, a public insurer is assumed to take a public perspective that values life years and quality-adjusted life years gains beyond the health care costs outlays and therefore wants the private payers to invest in these cures. Private payers would value HealthCoins because they can sell these coins to another insurer if a beneficiary leaves their rolls and also because they are able to recruit a patient who is cured of that disease at the point of recruitment, which would mean less expected health care costs over the subsequent years. This is especially important under the Affordable Care Act that disallows private payers to deny coverage based on pre-existing conditions.

A concept like HealthCoin, in principle, should go beyond a typical social impact bond and be able to address many problems associated with efficient financing of cures in the presence of multiple private payers. This is illustrated in . Health plans would give serious considerations to the upfront costs of cures and the returns on their investments in the form of Health Coins, which they can now trade. The key feature in this market is that when a patient decides to enroll in a new health plan, private or public, that new plan must purchase these Health Coins to enroll the patient to its rolls. In most cases, Health Coins would be traded virtually between the payers, with residual adjustments with real dollars made at year-end, thereby reducing transaction costs. In lieu of patient’s death these Health Coins transfer as debts to patients, which they may be able to insure against through life-insurance products. This last part, which involves some amount of risk-sharing with individual patients that they can re-insure, is important since financing the full upfront costs of cures through premiums could be prohibitive Citation[4]. Instead, the impact on premium for private health insurance products would be more moderate with Health Coins as private payers need to distribute only the net costs of buying and selling these units. Moreover, early investments in these cures could decrease the prevalence of the disease in older life thereby reducing the budget impact of these cures for Medicare and the impact on premium for Medicare Advantage plans.

An extensive version of this currency formulation could incorporate patients engaging in proven and well-established health promotion behaviors to add to these Health Coins, which their current payers could secure through premium subsidies to the patients. Physicians would continue to play a critical role at the center of this exchange. Generating Health Coins for a payer could be used as a separate dimension of reimbursements for physicians, which could better incentivize physicians to deliver life-saving interventions at lower costs and to engage patients to invest in health promoting behavior.

Conclusions

Given the disaggregated nature of the health care system in the US, investments in patient’s health and in long-term innovation can suffer if costly technology of today yields returns over long periods of time. Monetizing well-established and precise effects on health and cost-savings as a currency to be exchanged among the private and public payers could overcome these inefficiencies. An ensuing debate as to whether and how to develop such a currency can serve the US health care system well.

Acknowledgements

I thank two anonymous reviewers for their comments. The opinions expressed here is that of the author alone and do not reflect those of the University of Washington or the NBER.

Financial & competing interests disclosure

The author has no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

Notes

References

- Loftus P. Senate Committee is investigating pricing of Hepatitis C Drug. The Wall Street Journal 2014. Available from: http://online.wsj.com/articles/senate-finance-committee-is-investigating-pricing-of-hepatitis-c-drug-1405109206 [Last accessed on 11 August 2014]

- FDA approves first combination pill to treat hepatitis C. Available from: www.fda.gov/newsevents/newsroom/pressannouncements/ucm418365.htm [Last accessed on 18 October 2014]

- Mason C, Dunnill P. The strong financial case for regenerative medicine and the regen industry. Regen Med 2008;3(3):351-63

- Neuman T, Hoadley J, Cubanski J. The cost of a cure: Medicare’s role in treating hepatitis C. Health Affairs Blog 2014. Available from: http://healthaffairs.org/blog/2014/06/05/the-cost-of-a-cure-medicares-role-in-treating-hepatitis-c/ [Last accessed on 18 October 2014]

- Fulton BD, Felton MC, Pareja C, et al. Coverage, cost-control mechanism and financial risk-sharing alternative of high-cost healthcare technologies. California Institute for Regenerative Medicine Mimeo 2009. Available from: www.cirm.ca.gov/sites/default/files/files/about_cirm/UC-Berkeley%20final%20report%20to%20CIRM%2010.08.09.pdf [Last accessed on 18 October 2014]

- Hill A, Cooke G. Hepatitis C can be cured globally, but at what costs? Science 2014;345(6193):141-2

- Philipson T, von Eschenbach AC. Medical breakthroughs and credit market. Forbes, 2014. Available from: www.forbes.com/sites/tomasphilipson/2014/07/09/medical-breakthroughs-and-credit-markets/ [Last accessed on 2 August 2014]

- Gottlieb S, Carino T. Establishing new payment provisions for the high cost of curing disease. AEI Research 2014. Available from: www.aei.org/files/2014/07/10/-establishing-new-payment-provisions-for-the-high-cost-of-curing-disease_154058134931.pdf [Last accessed on 2 August 2014]

- Samuelson PA. The theory of public expenditure. Rev Econ Stat 1954;36:386-9

- Olson M. The logic of collective action. Public goods and the theory of groups. 2nd ed Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA: 1971

- Coase RH. The problem of social cost. J Law Econ 1960;1-44

- Azemati H, Belinsky M, Gillette R, et al. Social Impact Bonds: Lessons learned so far. Community Development Investment Review.. Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco. Available from: www.frbsf.org/community-development/files/social-impact-bonds-lessons-learned.pdf [Last accessed on 11 August 2014]