Economic Evaluation in Immunization Decision Making

Toronto, Ontario, Canada, Monday, 25 November 2013

To discuss the potential for systematically incorporating economic evaluation into immunization decision-making in Canada, the Vaccine Industry Committee of BIOTECanada, together with the Public Health Agency of Canada, academic vaccine researchers, economists, and modelers, held a workshop titled ‘Economic Evaluation in Immunization Decision Making’. The workshop brought together multiple interested parties to discuss opportunities and challenges in the Canadian system, learn about proposed best practices in this field, and consult about the optimal use of economic analysis in an overall coherent vaccine decision-making framework. Participants were asked to reflect on how economic evaluation can best fit in Canada, whether current standards for economic evaluation are sufficient, and how and by whom these evaluations should be conducted. In this paper, we summarize the workshop presentations and consultations as well as insights about what approaches may be needed and feasible in Canada.

Immunization has been lauded as a major public health achievement, leading to reductions in morbidity, mortality and long-term sequelae of infection. Although vaccines considered for introduction into public programs meet high standards for safety and efficacy, anticipated costs may prevent their immediate introduction into population-based public health programs. While the WHO recommends systematic use of economic evaluation in immunization decision-making processes by National Immunization Technical Advisory Groups Citation[1], a transparent, consistent and predictable process does not exist in Canada and many other countries. To discuss the potential for routinely incorporating economic evaluation into immunization decision-making in Canada, the Vaccine Industry Committee of BIOTECanada, together with the Public Health Agency of Canada, academic vaccine researchers, economists and decision-analytic modelers, held a workshop to determine the challenges and opportunities within a Canadian context.

The Canadian context for immunization decision-making & the consideration of economic issues

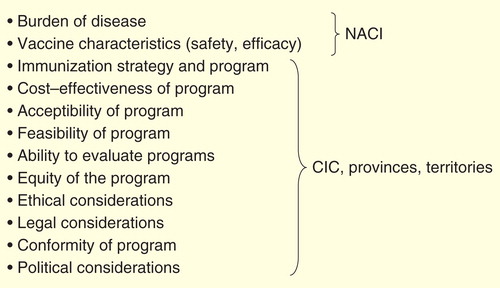

The workshop began with presentations on the current Canadian framework for immunization decision-making. Canada has a decentralized health system with federal, provincial and territorial health systems that share responsibility for delivering health care and public health programs. Canada’s National Immunization Technical Advisory Group, the National Advisory Committee on Immunization (NACI), has provided medical and scientific advice on immunization for Canadians since 1964 Citation[2]. Since the planning and implementation of programs is under the purview of provinces and territories Citation[2], the number of vaccines provided in public programs and their schedules differ across jurisdictions Citation[3] similar to Spain or Italy, also federal countries Citation[4]. In 2003, a National Immunization Strategy was implemented as a federal, provincial and territorial initiative with the objectives of improving equity of access to vaccines, increasing coordination of safety monitoring, program planning and immunization registries, development of national goals and objectives and other aspects of implementation Citation[5]. This was supported by a federal commitment of C$45 million over 5 years to strengthen a national collaboration framework and C$300 million over 3 years in the 2004 federal budget for an immunization trust to introduce four new vaccines Citation[6]; another C$300 million 3-year trust was also funded in 2007 to support the introduction of HPV vaccines. The National Immunization Strategy accepted an analytic framework for immunization decision-making, in which cost-effectiveness is one of 13 information categories for consideration Citation[7]. In 2004, other national bodies were created to strengthen public health (the Public Health Agency of Canada and the Pan-Canadian Public Health Network), and a federal, provincial and territorial committee was established (the Canadian Immunization Committee) separate from NACI with the responsibility for planning and delivery of immunization programs, including economic considerations Citation[2].

Within the 3-year period of each immunization trust, all 13 provinces and territories provided coverage for new childhood and adolescent vaccines against varicella, pertussis, invasive pneumococcal and meningococcal disease and HPV Citation[8]. The establishment of the National Immunization Strategy was also associated with lower prices through bulk purchasing and improved supply chain management Citation[8]. Since the expiration of the immunization trust funding, a disparity of immunization schedules across provinces has re-emerged across Canada Citation[9]. As well, the phenomenon of ‘recommended but unfunded vaccines’ – considered safe and effective by the NACI, but not publicly funded – has been noted Citation[10]. There are diverse challenges to coordinated immunization decision-making in countries with decentralized health care delivery. However, the inconsistent approach to economic evaluation of vaccines across provinces could be an obstacle to program implementation, and may also lead to decisions that do not reflect the values of all stakeholders Citation[10,11].

The global context for immunization decision-making with regard to economic issues

The 2006–2015 WHO Global Immunization Vision and Strategy called for countries to make ‘rational, evidence-based decisions about the choice of new vaccines and technologies’ Citation[12]. Systematic consideration of economic impact (future disease burden to the health care system, cost of disease including the impact of epidemics on social and political structures, cost and cost–effectiveness and affordability of immunization) was identified as an element of decision-making for National Immunization Technical Advisory Groups as a means to achieving sustainable introduction of new vaccines Citation[1,12]. Consideration of economic impact has been introduced in many advanced-economy countries, notably countries with federal system: the USA Citation[13] the UK Citation[14] and Australia Citation[15].

Implications of public health decision-making processes for industry & innovation

Presentations from industry noted the need for clear and transparent decision-making frameworks for evaluation of economic considerations. The lack of clear and consistent payer processes globally can present significant challenges for industry innovators, who must make costly research and development (R&D) decisions based on expected return on investment for new products Citation[16]. These challenges are amplified in an environment of health system austerity, increased R&D costs and diminishing revenues. Inconsistent payer decisions or delays in uptake of new products can also lead to lower-than-anticipated sales which are highly correlated with company profitability, stock prices and future expenditures on development R&D Citation[17].

Future innovation and potential benefits to future patients, it can be argued, rely on clear and explicit definitions from payers regarding what is needed and valuable accompanied by efficient and consistent appraisal and decision processes. Although there is considerable upstream collaboration between regulators and industry regarding evidence requirements for regulatory approval, the same level of engagement does not exist between industry and payers (and their respective immunization decision-making bodies) Citation[18]. Uncertainty about information relevant to payer decisions introduces considerable risk for industry and not addressing these knowledge gaps can delay the introduction of new vaccines, increase R&D costs and potentially increase future product prices Citation[19]. Upstream discussion and consensus regarding necessary evidentiary requirements, what vaccine innovations and products are needed and valuable and program approval expectations can mitigate these risks.

Immunization decision-making bodies that include economic evaluation in their scope must also embrace principles of neutrality, transparency, fairness and accountability (i.e., principles of moral social choice) while using consistently applied analytic methods and incorporating a wide range of stakeholder perspectives and societal value Citation[20]. To be effective, these processes should be linked to, or accountable for, budgetary decisions and payers. Ideally, they would be designed to meet overlapping health system and industry policy goals with respect to providing access to new technologies to improve health.

Successful models of use of economic evaluation in health care decision-making in Canada

Presentations from established Canadian health technology assessment bodies, Health Quality Ontario (HQO) and the pan-Canadian Oncology Drug Review (pCODR) provided lessons about the successful implementation of economic evaluation into recommendatory and decision-making frameworks. One of the functions of HQO is to improve the use of medical technology within the Ontario provincial health system Citation[21]. It is founded on a neutral and impartial analysis based on the principles of evidence-based medicine and consideration of social values and preferences, along with robust economic evaluation using standard methods Citation[22] that may also require decision-analytic approaches. These analyses are then used to inform a process of deliberation that includes representative stakeholders including the public, clinicians, economists and, to a limited extent, industry Citation[21]. The intent is to ground decision-making in the values of Ontarians with respect to health and health technology. The experience of HQO has informed the development of a provincial and territorial health technology assessment process for new oncology drugs, pCODR.

pCODR was developed and implemented to reflect the unique structure of Canadian health care delivery. Like the HQO, pCODR is predicated on impartial knowledge synthesis and analysis, followed by deliberation with an expert committee, to provide non-binding recommendations for the use of new oncology drugs. Individual provinces then make their own decisions on what drugs should be reimbursed in their jurisdictions. The pCODR expert committee explicitly considers evidence of clinical effectiveness, cost–effectiveness and patient value. In addition to aspiring to more consistent and timely listing decisions, another perceived benefit of this coordinated approach is efficiency of leveraged resources to produce rigorous evaluation, as some provinces have the capacity to perform these assessments while others do not.

pCODR was implemented in 2011 in an environment of increasingly expensive new cancer therapies, an accelerated pipeline of new therapies and wide cross-provincial variation in access. Provinces also differed greatly in their capacity to evaluate new technologies, with a limited and geographically dispersed pool of economic and modeling expertise in Canada. The development of pCODR required full participation and collaboration among provincial leaders, guided by principles of accountable governance, efficiency, continuous evaluation and a commitment to excellence.

Several key lessons from the development of pCODR were shared at the workshop. First is the need for active participation and ownership by its provincial end-users – in Canada, the participation of decision-makers in cancer agencies responsible for the delivery of new oncology products was critical and in line with best practices Citation[23]. Second, pCODR provided the needed support to facilitate the interpretation and use of cost-effectiveness information, specifically for those provinces without previous experience. pCODR also provides extra support to decision-makers to help them understand and use recommendations.

The value of clear and transparent communication to all stakeholders (ministries, agencies, patients, providers and producers) was another key lesson learned. pCODR makes publicly available documentation describing the decision process, the duration of the process, what products are being assessed, initial recommendation(s), summaries of deliberations, relevant background information including clinical and economic reports, all recommendation(s) and stakeholder feedback.

A final lesson from both pCODR and HQO processes was the need to develop a robust deliberative process. Deliberative processes (also deliberative methods) allow stakeholders with different perspectives and affected by the adoption of new technology to reflect on available evidence in a constructive and involved manner Citation[24]. Unlike the assessment of evidence, which involves scientific and other logic-based judgments, deliberative processes incorporate value-based judgments and are useful when there are issues of fairness and equity and significant uncertainty about social value. The pCODR deliberative process was inspired by the HQO model and further developed collaboratively with stakeholder participation. It uses explicit and clear definitions to help carefully guide discussion and encourage wider dialogue.

Are economic evaluations of vaccines different?

One presentation provided an overview of the emerging standards for economic evaluation and focused on specific challenges of the economic evaluation of vaccines compared to other health interventions. Communicable diseases differ from many other disease states because disease risk changes over time (i.e., is dynamic) as the number of cases in the population increases or decreases, leading to the potential for important ‘feedback’ whereby increasing case numbers can cause explosive epidemics, but increasing population-level immunity can result in communicable diseases being eliminated (from a local area) or eradicated altogether Citation[25]. This feedback, particularly when it results in herd immunity, constitutes a major component of the economic value of vaccines Citation[26]. Indeed, until recently, vaccination against childhood diseases provided a positive cost-benefit for society Citation[26], but total avoided expenditure could only be appreciated when the impact of vaccination on both program participants and non-participants was considered Citation[27]. There may also be other important dynamic effects that require consideration, including individual patient and provider behaviors, varying population demographics and density and geography. In some cases, consideration of these indirect effects may not improve cost–effectiveness; for example, reduced risk of infection as a result of decreased transmission drives up age at infection, which can increase the risk of complications of infection in later years. This has been seen with rubella vaccines and pregnancy Citation[28].

Unfortunately, modeling methods required to assess these dynamic effects may not be part of the traditional toolbox of disease modeling methods more widely used by health economists for chronic diseases (e.g., decision trees, semi-Markov models) Citation[28]. This means there is a risk that the value of dynamic effects such as herd immunity may not be considered by decision-makers Citation[27]. The challenge for assessment in Canada will be the required support and training for analysts and reviewers of these models to promote a greater understanding of when traditional methods are inappropriate and using recent expert consensus guidelines for modeling these effects Citation[29–31]. An additional challenge may be the time and material resources required to develop models that require additional data, software and training Citation[28].

Other issues in the health economic evaluation of vaccines apply more broadly to the evaluation of public health interventions, such as the complexity of interventions, the wider social and environmental costs that require consideration and how to best consider equity. The reader is referred to more in-depth analyses of these issues Citation[32].

The local perspective

The final set of presentations was given by provincial decision-makers, who described their experience with using economic evaluations in decision-making. Provinces have different capacities to conduct or use economic evaluations, and those with fewer available resources become more reliant on analyses performed elsewhere, which may not be fully appropriate for their local context. Economic evaluations that provide a range of relevant policy options and therefore could be applied to multiple settings would be of assistance. Some provinces have routinely incorporated economic evaluation into decision-making, and this has helped to establish flexible prices and price negotiation that reflects the economic value of the product as well as programs that are seen to meet local needs. At the local level, the economic impact of immunization must be weighed with the value of other public health programming. Even highly cost-effective vaccines may entail significant budget impact (and opportunity costs) and be unaffordable to provinces that are hoping to remain cost neutral (or cost reducing) from investments in new vaccines. The dynamic nature of price and its relationship to tendering and supply chain management is a particular characteristic of the Canadian situation and also requires consideration.

Summary

Following plenary sessions, participants were divided into groups to consult about several key questions, including how economic evaluation could be systematically integrated into immunization decision-making in Canada, what standards should be used to judge the quality of evaluations and who should perform and critically evaluate the analyses so they meet an acceptable standard for users.

Participants agreed that a transparent, systematic, accessible and high-quality process for including economic evaluation is needed for Canadian immunization decision-makers, and that leadership is needed to make this a national process. There was a general agreement that there are established guidelines for conducting economic evaluation and these do not need to be reinvented. Given the increased complexity of economic evaluation of vaccine programs and the relatively small pool of economists and modelers in Canada, there is a need to increase the capacity to plan, conduct and interpret economic analyses through shared and leveraged action. Participants noted that expert support to immunization committees, to include those trained in economics or mathematical modeling, will be necessary to facilitate informed discussion.

Although avoidance of duplication of effort is wise, participants noted that the commissioning of two analyses concurrently could provide insight and strengthen confidence in decision-making. International efforts to avoid duplication, increase capacity Citation[28] and share the products of economic evaluation of vaccines across countries, such as the establishment of the WHO Collaborating Center for evidence-informed immunization policy-making Citation[33], are opportunities learning about collaboration across jurisdictional boundaries.

A process for independent funding of economic evaluation to address questions from all stakeholders (regulatory through to end-users) could increase the credibility of these analyses. The need for early engagement and collaboration of multiple stakeholders was seen as important. Technical aspects discussed were the advantages and disadvantages of the perspective taken during an economic evaluation of a vaccine (e.g., payer or societal) and recommended discount rates.

Participants voiced concern about a lack of an immunization registry, which is necessary to determine coverage rates and vaccine efficacy, and the need for Canadian surveillance and disease incidence data, rather than reliance on data from other countries to provide model inputs. Participants observed that many lessons could be learned from the HQO/pCODR approach, especially the use of a deliberative process. While NACI has explicit methods for knowledge synthesis and recommendation development, the deliberative process is not clearly articulated and economic considerations are not explicitly considered Citation[34]. The pCODR and HQO deliberative processes include participation by multiple affected stakeholders during deliberation explicit definitions and decision rules and clear communication regarding expectations and timing. Consideration of Canada’s uniquely decentralized structure and a willingness to collaborate across geographic and political boundaries will be needed.

Based on workshop discussion, some feasible next steps in Canada, all involving additional consultation, appear to be: to explore with provincial implementation committees what (at minimum) recommendations and analyses based on cost–effectiveness are required by provinces; to achieve multi-stakeholder (patients, academia, industry, provinces) consensus as to the timing and relevant decision-making framework (i.e., both the information/data requirements and process to consider them) used to support decision-making at the local and national level; to examine options with the research community, provinces and industry for increasing the capacity to conduct and interpret economic evaluation through shared resources and common guidance while improving access to administrative and surveillance data to support more robust economic evaluation.

Supplementary Material

Download MS Word (21.5 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the meeting attendees and presenters (list of meeting attendees and presenters can be found online at www.informahealthcare.com/suppl/10.1586/14760584.2014.939637).

Financial & competing interests disclosure

Support for the meeting and manuscript was provided by BIOTECanada’s Vaccine Industry Committee. D Husereau received payment for drafting the manuscript and JM Langley received reimbursement of expenses for travel to the workshop, and JM Langley’s institution has received research funding from Merck Inc, Sanofi Pasteur, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, and Pfizer. D Fisman has received vaccine-related research grants from Sanofi Pasteur Canada, Novartis Vaccines, GlaxoSmithKline Vaccines, and has also received unrestricted educational funding from these companies as well as Merck Vaccines, in support of the FitzGerald Seminar series at the University of Toronto. A Chit and R VanExan are employees of Sanofi Pasteur Ltd. A Chit is a former employee of GlaxSmithKlines Vaccines. R Van Exan is a member of the Vaccine Industry Committee of BIOTECanada. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

We would especially like to thank Sara Rafuse, Principal of the Rafuse Consulting Group, who served on the organizing committee and provided key support for facilitating this meeting and writing assistance for this draft.

Notes

References

- Duclos P. National Immunization Technical Advisory Groups (NITAGs): guidance for their establishment and strengthening. Vaccine 2010;28(Suppl 1):A18-25

- Ismail SJ, Langley JM, Harris TM, et al. Canada’s National Advisory Committee on Immunization (NACI): evidence-based decision-making on vaccines and immunization. Vaccine 2010;28(Suppl 1):A58-63

- Sibbald B. One country, 13 immunization programs. CMAJ 2003;168:598

- Freed GL. The structure and function of immunization advisory committees in Western Europe. Hum Vaccin 2008;4:292-7

- Public Health Agency of Canada GoC. National Immunization Strategy (NIS). Government of Canada; 2010

- Public Health Agency of Canada GoC. Canadian National Report on Immunization, 2006. CCDR; Caanda: 2006. 32S3: p. 1-44

- Erickson LJ, De Wals P, Farand L. An analytical framework for immunization programs in Canada. Vaccine 2005;23:2470-6

- Public Health Agency of Canada Government of Canada. Interim evaluation of the National immunization strategy April 2003 to June 2007. Government of Canada; Ottawa: 2008

- Macdonald N, Bortolussi R. A harmonized immunization schedule for Canada: a call to action. Paediatr Child Health 2011;16:29-31

- Scheifele DW, Ward BJ, Halperin SA, et al. Approved but non-funded vaccines: accessing individual protection. Vaccine 2014;32:766-70

- Black S. The role of health economic analyses in vaccine decision making. Vaccine 2013;31:6046-9

- Immunization Vaccines and Biologicals, World Health Organization. Global immunization vision and strategy. UNICEF; Geneva: 2011

- Smith JC. The structure, role, and procedures of the U.S. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). Vaccine 2010;28(Suppl 1):A68-75

- Hall AJ. The United Kingdom Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation. Vaccine 2010;28(Suppl 1):A54-7

- Nolan TM. The Australian model of immunization advice and vaccine funding. Vaccine 2010;28(Suppl 1):A76-83

- Hartz S, John J. Contribution of economic evaluation to decision making in early phases of product development: a methodological and empirical review. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 2008;24:465-72

- Golec JH, Vernon JA. European pharmaceutical price regulation, firm profitability, and R&D spending, NBER working paper No. 12676. National Bureau of Economic Research; Cambridge MA: 2006

- Tsoi B, Masucci L, Campbell K, et al. Harmonization of reimbursement and regulatory approval processes: a systematic review of international experiences. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res 2013;13:497-511

- Philipson TJ, Jena AB. Striking a balance on new technology. cost-effectiveness analysis can help sort out emerging health care technologies, but what are the consequences for continued medical innovation? AHIP Cover 2006;47:29-31-3

- Drummond M, Brown R, Fendrick AM, et al. Use of pharmacoeconomics information – report of the ISPOR Task Force on use of pharmacoeconomic/health economic information in health-care decision making. Value Health 2003;6:407-16

- Johnson AP, Sikich NJ, Evans G, et al. Health technology assessment: a comprehensive framework for evidence-based recommendations in Ontario. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 2009;25:141-50

- (CADTH). Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health. Guidelines for the Economic Evaluation of Health Technologies. CADTH; Ottawa:Canada: 2006

- Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). Health Technologies and Decision Making. OECD; Paris: 2005. p. 160

- Culyer AJ. Deliberative processes in decisions about health care technologies: combining different types of evidence, values, algorithms and people. 2009

- Giesecke J. Modern infectious disease epidemiology. Second edition. London: Arnold, a member of the Hodder Headline group, 2002.

- Jacobs P, Yim R, Ohinmaa A, Varney J. Economics of childhood immunizations in Canada: data book. Institute of Health Economics; Edmonton, Alberta

- Brisson M, Edmunds WJ. Economic evaluation of vaccination programs: the impact of herd-immunity. Med Decis Making 2003;23:76-82

- Walker DG, Hutubessy R, Beutels P. WHO Guide for standardisation of economic evaluations of immunization programmes. Vaccine 2010;28:2356-9

- Pitman R, Fisman D, Zaric GS, et al. Dynamic transmission modeling: a report of the ISPOR-SMDM Modeling Good Research Practices Task Force Working Group-5. Med Decis Making 2012;32:712-21

- Karnon J, Stahl J, Brennan A, et al. Modeling using discrete event simulation: a report of the ISPOR-SMDM Modeling Good Research Practices Task Force – 4. Value Health 2012;15:821-7

- Macal CM, North MH. Tutorial on agent-based modelling and simulation. J Simulation 2010;4:151-62

- Edwards RT, Charles JM, Lloyd-Williams H. Public health economics: a systematic review of guidance for the economic evaluation of public health interventions and discussion of key methodological issues. BMC Public Health 2013;13:1001

- Isabelle W, Duclos P. Editorial The Health Policy and Institutional Development Unit of AMP is WHO Collaborating Centre for evidence-informed immunization policymaking. 2013. Available from: www.sivacinitiative.org

- National Advisory Committee on Immunization (NACI). Evidence-based recommendations for immunization – methods of the National Advisory Committee on Immunization. An Advisory Committee Statement (ACS). Can Commun Dis Rep 2009;35:1-10