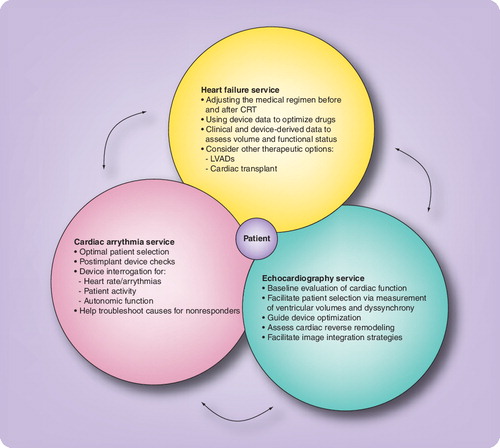

Arrows represent the two-way communication of information between the different services to facilitate optimal care.

CRT: Cardiac resynchronization therapy; CRT-D: Cardiac resynchronization defibrillator; LVAD: Left ventricular assist device.

Heart failure (HF), a final common pathway for the majority of cardiovascular illnesses, affects nearly 5 million Americans. As the population ages and the prevalence of cardiac risk factors continues to climb, the incidence of HF will increase. The fiscal impact of HF on the national exchequer is colossal since it constitutes the number one hospital diagnosis-related group in Medicare patients. The estimated combined direct and indirect cost in 2006 for HF in the USA was US$29.6 billion, and this will continue to grow, with 550,000 new cases of HF diagnosed each year Citation[1].

Electrical therapy for heart failure

Despite pharmaceutical advances, patients with HF reach a stage when they become refractory to medical therapy and remain at-risk for either progressive pump failure or sudden death. The advent of device therapy in the form of either cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) and/or defibrillator therapy has provided a new lease of life for many such patients. CRT has gained widespread acceptance as a safe and efficacious therapeutic measure for patients with advanced HF with evidence of systolic dysfunction (ejection fraction < 35%), conduction tissue disease (QRS duration > 120 ms) and persistent cardiac symptoms (New York Heart Association class III and IV). CRT and CRT with defibrillator therapy, involves placement of right atrial, right ventricular and left ventricular leads to restore synchronous ventricular contraction. Optimizing the timing of left and right ventricular contraction to one another through cardiac pacing offsets the mechanical inefficiency caused by dyssynchronous mechanical activation owing to the conduction disease. Several prospective randomized studies have shown that CRT is associated with significant improvement in hemodynamics and functional status, reduction in hospitalization rates for HF and enhanced long-term survival Citation[2–4]. These implantable devices have appreciably altered the natural course of ventricular failure and exert their physiological impact through improved myocardial contraction, reduction in mitral regurgitation and enhanced left ventricular filling Citation[5]. Ventricular remodeling occurs over time with a reduction in left ventricular volumes and improvement in ejection fraction Citation[6,7]. Of note, despite enhanced patient selection strategies and technological advances in devices and left ventricular lead systems, nearly a third of patients remain nonresponsive to the implanted device Citation[8]. Worsening HF requiring emergent care and recurrent hospitalizations has a negative impact on the cost–effectiveness of this therapeutic modality in a substantial minority of treated patients.

Integrating care: the need

The high prevalence of HF and the increasing patient population that is eligible for device therapy has created a new genre of ambulatory HF patients with implanted devices. The complex nature of heart disease in these patients often results in the need for integrated care from their internist, primary cardiologist, electrophysiologist (EP) and HF specialist with echocardiography support. Unfortunately, in most centers there is no structured cross-talk between the cardiac subspecialties and several weeks may pass between individual evaluations, resulting in disjointed, and often less than optimal, medical care. Current postdevice implant care is lacking on many fronts, namely: attention to device diagnostic information and use of such data to titrate medications; evaluating and maximizing device response in patients; and, more importantly, identifying and treating nonresponders. Currently, nonresponsive patients usually come to attention as a result of HF exacerbation or a hospitalization. One of the goals of an integrated healthcare delivery program is to detect problems early, with proactive modification of the drug regimen or device settings to prevent acute disease decompensation.

Although each subspecialty has an important independent role to play , the disciplines need to be integrated to further the care of the patient. A multidisciplinary clinic approach can facilitate better patient selection, CRT device optimization and careful titration of medical therapy in the post-implantation period. CRT devices record and provide detailed information pertaining to patient activity, heart rate, autonomic activity and transthoracic impedance; in the near future, they will also provide real-time hemodynamic data (Box 1). A multidisciplinary clinic provides an ideal structure for consultation between different specialties to allow these data to be used more efficiently in the care of these patients.

Although the EP implants and interrogates the CRT device, it is the HF specialist who can best assess the volume and functional status of the patient and optimize the medical regimen. The interdependence of the specialties is exemplified by the fact that the adjustment of the medications can be aided by using the longitudinal diagnostic data obtained from the device interrogation. Response to therapy is assessed via clinical improvement and echocardiographic evidence of reduction in ventricular dyssynchrony, positive ventricular remodeling and improved contractility. Nonresponsive patients can have their device programming optimized, through adjustment of certain parameters (the atrioventricular and inter-ventricular timings) with echocardiographic guidance Citation[6]. The Multispeciality clinic provides the opportunity to implement optimization protocols to treat nonresponders, maximize device benefit (even in responders) and integrate echocardiography and device diagnostic information into the clinical care of these patients. The closed circuit of such an approach also provides feedback to the device implanting physician, which, in turn, enhances ventricular lead implantation and positioning strategies. Unfortunately, there is no one-size-fits-all strategy and peri-implant care needs to be individualized based upon the clinical characteristics and cardiac substrate of the patient. Dedicated multidisciplinary programs enhance this collaborative care model and facilitate cross-training among specialties, enabling the provision of optimal care and potentially improving patient outcomes. Postdevice implantation, the hemodynamic status changes and the heart remodels, which, in turn, impacts the ventricular filling and contractility patterns. In order to keep pace with this evolving pattern, it appears intuitive that one needs to proactively institute medication and device programming changes, on an individualized basis Citation[9]. However, such care would only be possible through an integrated healthcare delivery setup. Recently, remote monitoring of these devices has become possible, and ambulatory information regarding the heart rate, physical activity and development of incipient pulmonary edema (e.g., transthoracic impedance measure) can be transmitted from these implanted devices either voluntarily or automatically via the internet. Although this advent of remote device monitoring has increased the risk of information overload, it provides the opportunity to enhance the quality of patient care. Web-based monitoring of these patients and their devices provides the option for the different subspecialists to share patient data and individualize treatment. In addition, ongoing work to enhance sensor technology has enabled over-the-web transmission of other important parameters (e.g., blood pressure, weight and oxygen saturations). In turn, this has augmented the level of sophistication routinely available for managing patients with HF, calling for a structured multidisciplinary approach to this patient population.

Multispeciality care: the new model?

HF management programs have been shown to be successful in improving quality of life and patient satisfaction, while reducing hospital admissions and hospital stay Citation[10]. Many such models involving home care and specialized nursing follow-up for patients with HF (without CRT devices), have also been shown to improve clinical outcome. A recent meta-analysis of multidisciplinary strategies involving specialized nurses and follow-up strategies have demonstrated a 27% reduction in hospitalization rates and a 43% reduction in HF hospitalizations Citation[10]. Such disease management programs have been shown to be successful, with short-term gains subsequently being translated into long-term gains through improved outcomes and reduced medical care costs.

However, it is important to note that these multidisciplinary approaches have neither involved HF patients with implanted devices, nor have they involved care across the specialties. Although it appears intuitive that this multispecialty model would translate into better patient care, the impact of such integrated services will need to be assessed prospectively. Besides hard endpoints, such as cardiovascular events, hospitalization for heart failure and total mortality, other measures, such as quality of life, cost–effectiveness, patient satisfaction and physician efficiency, will also need to be evaluated.

Advances in medical technology strain the finite healthcare resources, necessitating the demonstration of cost–benefit advantages of new technological approaches. The clear benefit of device therapy in the symptomatic patient refractory to conventional medical therapy has brought up the possibility of expanding its role to the well-controlled HF patients (New York Heart Association class I and II), as well as to some subjects with a narrow QRS but with echocardiographic evidence of mechanical dyssynchrony Citation[11,12]. As the population eligible for device therapy rapidly expands, the need to be more cognizant of its cost–effectiveness and to refine the selection criteria will become more important. In order to ensure that we accurately select the patient most likely to respond, recognize early the nonresponder and accordingly alter the drug–device therapy, communication lines between the EP, echocardiographer and HF specialist need to be facilitated. An integrated multidisciplinary approach involving the different cardiac subspecialties for treating HF patients with device therapy has been overdue and some centers have begun moving in that direction.

Having recently implemented such a multidisciplinary clinic at our institution, it is important to emphasize that such an endeavor requires buy-in from the different disciplines and considerable resources from the parent institution. It is understandable that this might not be achievable everywhere and, possibly, will be restricted to major academic centers. This obviously brings up the question as to whether an equivalent level of care can be provided by a single physician or subspecialty. Although this is possible, it would require a significant amount of cross-training among the different subspecialties. For example, a HF physician would clearly need to acquire a considerable measure of device therapy experience (implantation, interrogating, programming and trouble-shooting), as well as insight into echocardiographic and other imaging techniques to assess for mechanical dyssynchrony and reverse remodeling in order to to be able to single-handedly, comprehensively manage this patient group. The same applies to the EP, who would need to learn the skill set of the HF physician, be willing to spend more time manipulating the drug therapy regimen and understand the echocardiographic techniques. The advent of remote monitoring of these devices and frequent electronic data transmissions of physiological parameters (e.g., weight or blood pressure), although enhancing the level of patient care, has further complicated the division of labor amongst the different subspecialties. As this population of patients with HF and implanted devices continues to increase, it becomes clear that the current status quo will not work, and it obligates us to ask the question: is multidisciplinary care the best approach or is it time to create a new subspecialty?

Box 1. Diagnostic features in cardiac resynchronization therapy devices for managing the heart failure patient.

Heart failure diagnostics

| • | Parameters - Resting heart rate - Patient activity log - Heart rate variability - Standard deviation of the average normal-to-normal intervals - Heart rate variability footprint - Autonomic balance monitor - Percent pacing - Detection of atrial or ventricular arrhythmias - Ventricular rate during atrial arrhythmias - Transthoracic impedance (OptiVol®) | ||||

| • | Hemodynamic measures -Pulmonary artery pressure - Right ventricular pressure - Right ventricular dP/dt - Left atrial pressure | ||||

Rhythm management

| • | Atrial fibrillation episodes | ||||

| • | Supraventricular arrhythmias | ||||

| • | Ventricular arrhythmia | ||||

Therapy delivery

| • | Antitachycardia pacing | ||||

| • | Implantable cardioverter defibrillator shocks | ||||

Device management

| • | Pacing lead thresholds | ||||

| • | Electronic repositioning | ||||

| • | Biventricular pacing during atrial fibrillation | ||||

| • | Atrioventricular timing | ||||

| • | Interventricular timing | ||||

Financial disclosure

The author has no relevant financial interests related to this manuscript, including employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

References

- Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics – 2006 Update. A report from the American heart association statistics committee and stroke statistics subcommittee. Circulation14, 1–67 (2006).

- Bradley DJ, Bradley EA, Baughman KL et al. Cardiac resynchronization and death from progressive heart failure, a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. JAMA289, 730–740 (2003).

- Bristow MR, Saxon LA, Boehmer J et al. Comparison of Medical Therapy, Pacing, and Defibrillation in Heart failure I. Cardiac-resynchronization therapy with or without an implantable defibrillator in advanced chronic heart failure. N. Engl. J. Med.350(21), 2140–2150 (2004).

- Cleland JG, Daubert JC, Erdmann E et al. The effect of cardiac resynchronization on morbidity and mortality in heart failure. N. Engl. J. Med.352, 1539–1549 (2005).

- Kass DA. Ventricular resynchronization: pathophysiology and identification of responders. Rev. Cardiovasc. Med.4(Suppl. 2), S3–S13 (2003).

- Yu CM, Chau E, Sanderson JE et al Tissue Doppler echocardiographic evidence of reverse remodeling and improved synchronicity by simultaneously delaying regional contraction after biventricular pacing therapy in heart failure. Circulation105, 438–445 (2002).

- Sutton MG, Plappert T, Hilpisch KE et al. Sustained reverse left ventricular structural remodeling with cardiac resynchronization at one year is a function of etiology, quantitative Doppler echocardiographic evidence from the Multicenter InSync Randomized Clinical Evaluation (MIRACLE). Circulation113, 266–272 (2006).

- Abraham WT, Fisher WG, Smith AL et al. Cardiac resynchronization in chronic heart failure. 346, 1845–1853 (2002).

- O’Donnell D, Nadurata V, Hamer A, Kertes P, Mohammed W. Long-term variations in optimal programming of cardiac resynchronization therapy devices. Pacing Clin. Electrophysiol.28(Suppl. 1), S24–26 (2005).

- McAlister FA, Stewart S, Ferrua S et al. Multidisciplinary strategies for the management of heart failure patients at high risk for admission: a systematic review of randomized trials. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol.44, 810–819 (2004).

- Achilli A, Sassara M, Ficili S et al. Long-term effectiveness of cardiac resynchronization therapy in patients with refractory heart failure and ‘narrow’ QRS. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol.42(12), 2117–2124 (2003).

- Turner MS, Bleasdae RA, Vinereanu D et al. Electrical and mechanical components of dyssynchrony in heart failure patients with normal QRS duration and left bundle-branch block, impact of left and biventricular pacing. Circulation.109, 2544–2549 (2004).