Abstract

Prompt identification of individuals during the highly infectious acute or early stage of HIV infection has implications for both patient management and public health interventions. The studies on natural history of HIV infection over the last three decades have uncovered several clinical features and virological markers to diagnose early infection. However, the brevity of the acute symptomatic phase combined with the difficulty in identifying non-specific signs and symptoms poses diagnosis of early HIV infection as a remaining challenge. Furthermore, underestimation of risky behavior in the absence of detailed patient history and possible concurrent sexually transmitted infections render the diagnosis of recent infection difficult. Herein, we focus on the multifaceted clinical manifestations and the best usage of technological advancements to detect early HIV infection. Early diagnosis of HIV infection contributes to further improving patient outcomes and preventing transmission.

Three decades ago: a mononucleosis-like syndrome heralding the initial combat between virus & host

Acute HIV infection was first described by Cooper et al. in 1985 through the assessment of 12 seroconverted patients, with the ultimate finding that 11 of them had experienced a transient illness resembling infectious mononucleosis soon before HIV diagnosis Citation[1]. The symptoms usually occurred within 2 weeks following exposure and lasted from 3 to 14 days, most often including fever, pharyngitis, night sweats, lethargy and rash. Since this initial description, more symptomatic cases of acute HIV infection were recognized and reported, leading to the designation of ‘acute retroviral syndrome’ (ARS) to encompass signs and symptoms occurring during this seroconversion phase, which corresponds to acute or primary HIV infection (PHI). The awareness of this primary phase has contributed to enhancing detection and further characterizing this transient symptomatic phase. The incidence of symptomatic presentation of PHI ranges from 92 to 23% depending on the recruitment bias. Studies from hospital-based centers reported patients more severely affected compared to community medical centers and observational cohort studies Citation[2–4]. Most signs and symptoms of PHI are transient and non-specific, mimicking flu-like syndrome or acute mononucleosis syndrome. Moreover, the diagnosis can easily be missed in certain cases where the risk for HIV acquisition is underestimated, such as in older adults and females Citation[5]. Despite best efforts by healthcare professionals, the diagnosis of PHI remains difficult, as the symptoms are non-specific and transient and laboratory tests may not detect antibody response during this pre-seroconversion phase Citation[6,7]. However, early diagnosis exhibits immediate public health influence due to an 8- to 10-fold increase in the risk of secondary transmission during the early compared to chronic phase of infection Citation[8,9]. Furthermore, it has been shown that early initiation of ART can reduce AIDS and non-AIDS clinical events and decrease risk of secondary transmission Citation[10,11].

Signs & symptoms leading to a diagnosis of recent HIV infection

Commonly reported clinical manifestations of PHI include fever, malaise, pharyngitis, rash, headache and nausea . About half of the cases have digestive symptoms such as diarrhea, weight loss and vomiting. Lymphadenopathy usually presents as symmetrical lymph node enlargement less than 1 cm in diameter, predominantly in the cervical, axillary and inguinal regions. Of note, symmetrical occipital lymphadenopathy is a characteristic presentation of viral infections and should evoke consideration of HIV infection if encountered in an adult subject Citation[4]. These constellations of symptoms are not specific. However, their combination with the presence of symmetrical enlarged lymph nodes should contribute to clinical diagnosis Citation[12,13]. Notably, patients reported their transient illness as a unique experience characterized by an onset of fatigue and often recalled being bedridden for a few days. Clinical features differ slightly by the route of infection. Sore throat, oral and genital ulcers are more frequently observed in men who have sex with men (MSM) than in drug users, suggesting the presence of inoculation chancre induced by HIV Citation[4,12].

Table 1. Common and rare clinical manifestations associated with primary HIV infection.

Atypical manifestation of PHI: the importance of routine HIV screening

Misleading clinical presentation of PHI includes predominantly neurological or digestive manifestations. Neurological presentations have been reported, including Bell’s palsy, Guillain–Barré syndrome (peripheral polyradiculoneuritis), viral encephalitis, peripheral neuromotor disorder and acute psychiatric disorders Citation[14]. Infrequent as they remain, the diagnosis can be made through a systematic virological screening test, which justifies the immediate initiation of ART to alleviate symptoms Citation[14]. Digestive manifestations including unilateral or bilateral tonsillitis and severe gastritis can also be misleading, as they are often attributed to other infections or gastrointestinal conditions Citation[2]. In rare cases, opportunistic infections like cytomegalovirus (CMV) colitis or gastritis and oral or esophageal candidiasis have also been reported, where patients were diagnosed with an AIDS-defining event at the time of PHI, often associated with a CD4 count below 350 cells/μl Citation[15]. Other rare manifestations include alopecia, bacterial and Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia. Globally, the intensity of acute retroviral syndrome (ARS) and higher viral load measured at set point are predictive of a rapid decay of CD4 T-cell counts and disease progression.

Be on the lookout for ‘the great masquerader’ when other sexually transmitted infections collide with HIV

HIV screening is very important whenever any other sexually transmitted infection is diagnosed as patients may acquire HIV in the context of concurrent primary or secondary syphilis, gonorrhea, chlamydia or others transmitted infections, including herpetic and HCV infections Citation[16,17]. Due to increased sexually transmitted infection incidence and a status quo of less frequent condom use, only systemic screening of persons at risk may provide an early diagnosis in this ‘treatment as prevention’ era.

Routine laboratory testing

Patients undergoing PHI often present with transient elevation of liver enzymes with or without thrombocytopenia evoking a mononucleosis syndrome Citation[18]. Neutropenia and pancytopenia have been reported and generally wane in the absence of therapy. Less frequently cryoglobulinemia and anti-phospholipid syndrome have been reported. The index of suspicion of HIV infection remains a key element for diagnosis, particularly in the investigation of individuals exhibiting HIV risk behavior while traveling in zones of high prevalence. Interestingly, the CD4 to CD8 T-cell ratio can be used for the diagnosis of mononucleosis syndrome such as Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) and CMV infections. Likewise, an inverted CD4 to CD8 ratio is characteristic of HIV infection and may even present prior to seroconversion. The ratio can have practical relevance as the test results are available within 24 hours and strongly support the suspicion of infection while waiting for the confirmatory tests Citation[19]. Drug resistance testing should be performed at the initial visit to assess the presence of resistant mutant variants that will guide the selection of optimal ART and will be of relevance for epidemiological survey of transmitted drug resistance.

Testing for hepatitis B, C and syphilis should also be considered, as they share similar routes of transmission and may interact with clinical manifestations.

Improvements in the laboratory diagnosis of PHI

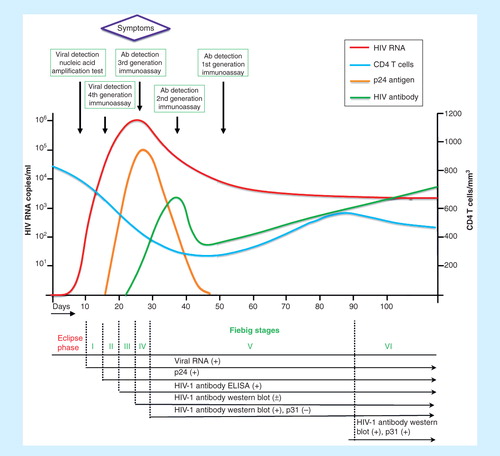

The definition of PHI generally covers the acute symptomatic phase spanning from the virus entry to the detection of an antibody response. The new immunoassays with improved sensitivity and specificity have reduced the interval between HIV acquisition and detection of sero-positivity from 21–30 days to 15 days. During the ‘window phase’ when antibodies are not yet detectable, the diagnosis must rely on the detection of viral antigen such as p24 and/or nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs). Due to the cost and time limitations of NAATs, third- and fourth-generation indirect immunoassays have become a routine. To reduce the eclipse phase, third-generation assays involve the detection of both IgM and IgG antibodies, while fourth-generation assays also include the assessment of p24 antigen. Based on this technology, the introduction of the Fiebig staging system has enabled a better estimate of the date of HIV acquisition by subdividing PHI to six phases Citation[20]. However, the Fiebig staging system only represents a mean estimation of time from viral acquisition, which limits its use in explaining individual variations in real clinical practices.

Figure 1. Trajectories of HIV-RNA viremia, CD4 T cells, p24 antigen and HIV antibody over the early phase of HIV infection. Sequence of appearance of different generations of HIV diagnostic assays is presented. Fiebig staging which represents a mean estimation of time from viral acquisition, divided into six phases, has also been superimposed. Eclipse phase is defined by the absence of any marker including p24 and viral RNA.

The development of new technology allows for an easier link between the clinical symptoms and a biological diagnosis of the infection. A confirmation test more sensitive than western blot, using recombinant proteins and synthetic peptides from HIV-1 and HIV-2, and a synthetic peptide from the rare subtype HIV-1 group O assay is currently available in Europe. Such assays will be able to reduce the window period and shift Fiebig V and VI stages to earlier time points.

The availability of rapid testing methods (20 min) self-operable by the patient can increase the frequency of screening procedures. However, the lower sensitivity and specificity of these rapid tests necessitate confirmation with standard serological testing Citation[21]. For example, the third-generation of rapid tests are equally sensitive as third-generation ELISA, while the current fourth-generation rapid tests tend to be somewhat less sensitive than the homologous ELISAs.

Quantitative HIV viral load (HIV RNA) testing is currently used in the clinical practice as a prognostic marker and as a criterion for treatment response and not as a diagnostic tool. However, such testing can be requested by a clinician to facilitate prompt diagnosis when faced with discordant screening results. More recently, qualitative molecular detection by real-time PCR or transcription-mediated assay can also be useful to facilitate prompt diagnosis. The HIV RNA determination based on real-time technologies, which are more sensitive and quantitative, will soon be available as clinical diagnostic tool for the window phase Citation[22].

Conclusion

Identification of individuals in the earliest phases of HIV infection remains a difficult task due to the added demands of repeat HIV testing and limitations of detection using currently available technologies. There is a need to increase awareness about common and rare features of PHI in healthcare personnel, community representatives and persons at high risk of HIV acquisition. New generation immunoassays combining p24 antigen and antibody testing shorten the window period to 10 days, leading to a more rapid diagnosis. The importance of early diagnosis of HIV infection represents a distinct opportunity to intervene with the potential to benefit the individual and prevent onward transmission. Treatment of acute and early HIV-1 infection with current ART regimen has shown the benefit of viral suppression, preservation of immune function and delayed disease progression. Moreover, early ART also contributes to a reduction in the size of viral reservoir, a decreased rate of viral mutation due to viral suppression and improved control of chronic inflammation. The importance of such early HIV diagnosis is undeniable as this period of time represents a critical opportunity for intervention to halt disease progression and limit onward transmission.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Angie Massicotte for coordination and assistance and Kishanda Vyboh and Alexandra Averback for a critical reading.

Financial & competing interests disclosure

This work was supported by the Fonds de la Recherche Québec-Santé (FRQ-S): Thérapie cellulaire and Réseau SIDA/Maladies infectieuses, Canadian Institutes of Health Research (grants MOP 103230 and CTN 257), the Canadian Foundation for AIDS Research (CANFAR; grant 023-512), and the Canadian HIV Cure Enterprise Team Grant HIG-133050 from the CIHR in partnership with CANFAR. JP Routy is the holder of Louis Lowenstein Chair in Hematology & Oncology, McGill University. W Cao is supported by CTN postdoctoral fellowship award and V Mehraj is supported by FRQ-S postdoctoral fellowship award. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed. No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

Notes

References

- Cooper DA, Gold J, Maclean P, et al. Acute AIDS retrovirus infection. Definition of a clinical illness associated with seroconversion. Lancet 1985;1(8428):537-40

- Braun DL, Kouyos RD, Balmer B, et al. Frequency and Spectrum of Unexpected Clinical Manifestations of Primary HIV-1 Infection. Clin Infect Dis 2015. [Epub ahead of print]

- Kinloch-de Loes S, de Saussure P, Saurat JH, et al. Symptomatic primary infection due to human immunodeficiency virus type 1: review of 31 cases. Clin Infect Dis 1993;17(1):59-65

- Routy JP, Vanhems P, Rouleau D, et al. Comparison of Clinical Features of Acute HIV-1 Infection in Patients Infected Sexually or Through Injection Drug Use. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2000;24(4):425-32

- Meditz AL, MaWhinney S, Allshouse A, et al. Sex, race, and geographic region influence clinical outcomes following primary HIV-1 infection. J Infect Dis 2011;203(4):442-51

- Poon AF, McGovern RA, Mo T, et al. Dates of HIV infection can be estimated for seroprevalent patients by coalescent analysis of serial next-generation sequencing data. AIDS 2011;25(16):2019-26

- Hecht FM, Wellman R, Busch MP, et al. Identifying the early post-HIV antibody seroconversion period. J Infect Dis 2011;204(4):526-33

- Pilcher CD, Tien HC, Eron JJJr, et al. Brief but efficient: acute HIV infection and the sexual transmission of HIV. J Infect Dis 2004;189(10):1785-92

- Brenner BG, Roger M, Routy JP, et al. High rates of forward transmission events after acute/early HIV-1 infection. J Infect Dis 2007;195(7):951-9

- Grinsztejn B, Hosseinipour MC, Ribaudo HJ, et al. Effects of early versus delayed initiation of antiretroviral treatment on clinical outcomes of HIV-1 infection: results from the phase 3 HPTN 052 randomised controlled trial. Lancet Infect Dis 2014;14(4):281-90

- Group ISS. Initiation of Antiretroviral Therapy in Early Asymptomatic HIV Infection. N Engl J Med 2015. [Epub ahead of print]

- Vanhems P, Routy JP, Hirschel B, et al. Clinical features of acute retroviral syndrome differ by route of infection but not by gender and age. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2002;31(3):318-21

- Wood E, Kerr T, Rowell G, et al. Does this adult patient have early HIV infection?: The Rational Clinical Examination systematic review. JAMA 2014;312(3):278-85

- Valcour V, Chalermchai T, Sailasuta N, et al. Central nervous system viral invasion and inflammation during acute HIV infection. J Infect Dis 2012;206(2):275-82

- Vanhems P, Voirin N, Hirschel B, et al. Brief report: incubation and duration of specific symptoms at acute retroviral syndrome as independent predictors of progression to AIDS. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2003;32(5):542-4

- Thomson EC, Nastouli E, Main J, et al. Delayed anti-HCV antibody response in HIV-positive men acutely infected with HCV. AIDS 2009;23(1):89-93

- Ward H, Ronn M. Contribution of sexually transmitted infections to the sexual transmission of HIV. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 2010;5(4):305-10

- Vanhems P, Allard R, Cooper DA, et al. Acute human immunodeficiency virus type 1 disease as a mononucleosis-like illness: is the diagnosis too restrictive? Clin Infect Dis 1997;24(5):965-70

- Lu W, Mehraj V, Vyboh K, et al. CD4:CD8 ratio as a frontier marker for clinical outcome, immune dysfunction and viral reservoir size in virologically suppressed HIV-positive patients. J Int AIDS Soc 2015;18:20052

- Fiebig EW, Wright DJ, Rawal BD, et al. Dynamics of HIV viremia and antibody seroconversion in plasma donors: implications for diagnosis and staging of primary HIV infection. AIDS 2003;17(13):1871-9

- Rosenberg NE, Pilcher CD, Busch MP, et al. How can we better identify early HIV infections? Curr Opin HIV AIDS 2015;10(1):61-8

- CDC. Laboratory Testing for the Diagnosis of HIV Infection: Updated Recommendations. In: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Association of Public Health Laboratories. 2014. Available from: http://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/23447 [Last accessed 21 July 2015]