Abstract

Biologic drugs have proved highly effective for the treatment of immune-mediated inflammatory diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA). These drugs are often considered cost-effective for well-defined RA patient populations not responding adequately to conventional treatment, but are used first-line relatively rarely, partly due to high costs. Furthermore, not all clinically eligible patients can access biologics even as second-line therapy. Recently, there has been a rise in interest in ‘biosimilar’ drugs that are highly comparable to the ‘reference medicinal product’ (RMP) in terms of efficacy and safety but may generally be lower in price. This review summarizes the cost burden of RA and considers the potential role of biosimilars in reducing drug costs and increasing patient access to biologics.

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic, systemic autoimmune disease, characterized by joint pain and stiffness, progressive destruction of joints and increasing functional disability. The ‘Global Burden of Disease 2010’ study estimated the worldwide prevalence of RA to be 0.24%, with at least twice as many women affected as men Citation[1]. The prevalence of RA is estimated to be highest in Australasia (mean 0.46%), Western Europe (0.44%) and North America (0.44%), and lowest in East/Southeast Asia and North Africa/Middle East (all with mean 0.16%) Citation[1]. Both genetic susceptibility and environmental triggers are believed to play key roles in RA development Citation[2,3].

RA results in considerable disability, accounting for 0.8% of all disability-adjusted life-years lost in Europe Citation[4]. Furthermore, RA has a significant and negative impact on all aspects of quality of life Citation[4]. Mortality is also increased in patients with RA, a finding that may reflect an increased incidence of cardiovascular disease in this population Citation[5]. Individual patients with RA differ widely with respect to progression of disease and clinical presentation Citation[2]. The health burden of RA also seems to vary according to certain socioeconomic factors; for example, countries with a low per-capita income show a relatively high health burden of disease, while macroeconomic conditions are a key factor affecting access to treatment, at least in some regions of Europe Citation[6,7].

RA-related costs are substantial, a fact due in large part to the high cost of biologic drugs such as infliximab and other TNF inhibitors. In this article, we describe the cost burden of RA and consider the impact of the recent introduction of so-called ‘biosimilar’ drugs as potentially cost-effective alternatives to ‘originator’ or ‘reference medicinal product’ (RMP) biologics. A biosimilar is defined by WHO as a “biotherapeutic product that is similar in terms of quality, safety, and efficacy to an already licensed reference biotherapeutic product” Citation[8]. In particular, this article will focus on data regarding the potential economic impact of CT-P13 (Remsima®, Inflectra®), a biosimilar of the infliximab RMP (Remicade®).

Economic burden of RA

The economic burden of RA mainly comprises indirect costs and direct medical and direct non-medical costs. Although there is a certain heterogeneity in the literature with respect of categorizing disease-related cost items, indirect costs usually include losses due to disability, unemployment and productivity loss. Direct medical costs include expenditure on drugs, hospitalization, surgery, tests and various related medical procedures, while costs of informal caregiver time, disease-related home remodeling and travel costs for health services are considered as direct non-medical costs. There are also intangible costs involved, which reflect the psychological distress and deterioration in quality of life that are often experienced by patients and their families. Although such intangible costs are somewhat harder to quantify than indirect and direct costs, they can be expressed to some degree in quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) either by direct measurements or via estimations based on the significant relationship between measures of functional status (e.g., the Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index [HAQ-DI]) and health-related quality of life (e.g., EQ-5D) Citation[9,10]. The Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ) is a comprehensive, self-reported, patient-oriented measure of outcome in patients with rheumatic diseases, including RA. This validated questionnaire is based on five patient-centered dimensions: costs of care, disability, medication effects, pain and mortality, and the higher the HAQ values, the more severe the outcomes Citation[11]. The disability assessment component of the HAQ, the HAQ-DI, assesses a patient’s level of functional ability. illustrates the statistically significant relationship between HAQ-DI and EQ-5D. As HAQ-DI increases (i.e., outcomes worsen), so quality of life (determined by EQ-5D) decreases Citation[9,10].

Figure 1. The relationship between functional status (measured using the Health Assessment Questionnaire [HAQ]) and a generic health-related quality of life measure (EQ-5D) in rheumatoid arthritis. As HAQ increases (i.e., outcomes worsen), so quality of life (determined by EQ-5D) also decreases Citation[9,10].

![Figure 1. The relationship between functional status (measured using the Health Assessment Questionnaire [HAQ]) and a generic health-related quality of life measure (EQ-5D) in rheumatoid arthritis. As HAQ increases (i.e., outcomes worsen), so quality of life (determined by EQ-5D) also decreases Citation[9,10].](/cms/asset/b6040b71-3434-4f12-86ae-6c0b6cf3ac39/ierm_a_1090313_f0001_b.jpg)

Indirect costs of RA

As a chronic disease that often begins when individuals are of working age, the indirect costs associated with RA are substantial. With so many individuals in employment affected, even small reductions in work capacity can cost tens of billions of dollars each year Citation[12]. The Medical Expenditure Panel Survey in the USA found that individuals with RA were 53% less likely to be employed, and spent 3.6-times as many days ill in bed as those without RA Citation[13]. A systematic literature review also revealed that a median of 66% of employed individuals with RA had been absent from work within the previous 12 months because of their RA, with a median duration of absence of 39 days (range 7–84 days) Citation[14]. In Sweden, 28% of a sample of 148 working-age patients with early-stage RA showed work disability at baseline; after 15 years, this had increased to 44% Citation[15]. Such data highlight the increase in work disability that occurs over time in RA patients.

Several studies in different countries have estimated the indirect costs of RA Citation[4,16–18]. A study published in 2010 estimated these costs in the USA to be $10.9 billion (in 2005 dollars) plus a further $9.6 billion due to premature mortality Citation[16]. In Canada, indirect costs have been estimated to account for 45% of total spending on RA Citation[17], while in Italy, these costs are believed to account for as much as 76% of total spending on the disease (€1210 million out of €1600 million in 2002) Citation[18].

Direct costs of RA

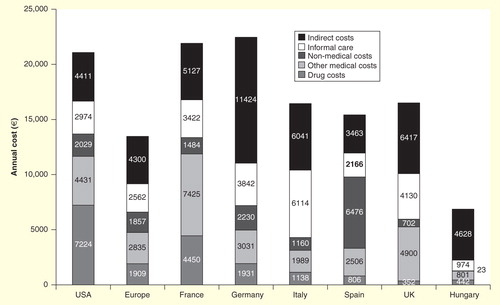

The direct costs of RA are substantial and vary between countries . Previously, hospitalization accounted for the bulk of direct medical costs of RA. Another direct cost of RA that places a burden on both individuals and society is long-term care (LTC). A study in Hungary, where LTC primarily consists of day care, nursing, chronic care and rehabilitation, found that the costs of LTC for RA patients were 32% higher than those for the general LTC population Citation[19]. Besides the professional care that is provided by the health and social care systems (direct medical costs), RA patients often receive informal care, that is, help by non-professional caregivers such as family members, for their everyday activities and self-care (direct non-medical costs). Although economic evaluations often ignore informal caregiving, the inclusion of informal care costs can impact on the results of economic evaluations of RA treatments Citation[20]. However, the largest expense now tends to be on drugs Citation[21]. In the most part, this is due to the introduction and costs of biologic drugs. This topic is discussed in greater depth in the following section.

Costs & cost–effectiveness issues with RMP biologics for RA

The treatment of RA and other immune-mediated inflammatory diseases (IMIDs) has been transformed by the introduction of targeted biologic therapies, which are able to improve symptoms and slow disease progression Citation[22–24]. However, biologic therapies are costly: a month’s supply of a biologic for the treatment of RA costs considerably more than a year’s supply of methotrexate Citation[25]. Consequently, the introduction of biologics has led to substantial increases in the direct costs of treating RA Citation[26]. For example, in the USA, annual direct costs per patient are estimated to be $10,000 to $30,000 Citation[21,27–29] versus approximately $3,000 when only ‘synthetic’ or ‘conventional’ disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (cDMARDs) are used Citation[27].

At a willingness-to-pay threshold of $50,000 per QALY gained, biologics are generally not considered cost-effective compared with cDMARDs in treatment-naïve patients in RA Citation[30]. It is important to note that most analyses were performed from the payer’s perspective. Such data have meant that use of biologics in RA is often restricted to the second-line setting. Another cost–effectiveness threshold used in some countries is three-times per-capita gross domestic product (GDP) per QALY, and a recent study has shown that estimates of cost–effectiveness for biologics in several IMIDs, including RA, were higher than this threshold in some middle-income countries Citation[31]. Relevant data also emerged in a recent systematic review which utilized data from 41 different cost-utility analyses in order to examine the cost–effectiveness of biologics in RA. At a threshold of €35,000 per QALY, TNF inhibitors were found not to be cost-effective in both cDMARD-naïve patients and those with an inadequate response to cDMARD treatment, if only direct costs were considered. However, with willingness-to-pay thresholds of €50,000 to €100,000 per QALY, biologics were possibly cost-effective in patients with an inadequate response to cDMARDs Citation[32]. Cost–effectiveness results were generally more favorable if indirect costs were also included; nevertheless, considerably fewer studies are available that performed analyses from a societal perspective. At best, such data appear to support use of RMP biologics only as second-line therapy.

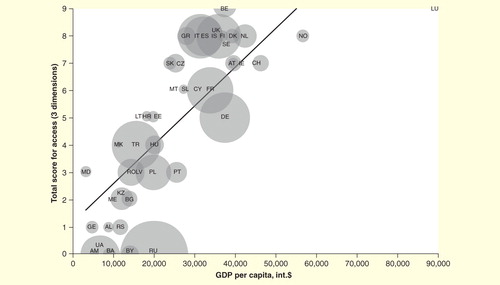

Beyond restriction to second-line use, the high cost of biologic therapies has led to additional access restrictions for some patients with RA. A study of 46 countries within the WHO European Region found that 10 countries did not reimburse any biologics for the treatment of RA Citation[33]. This study also showed that the treatment of a single patient for 1 year with a biologic exceeded per-capita GDP in 26 countries . The range was 0.18–11.05 times per-capita GDP for a biologic compared with 0.01–0.23 times per-capita GDP for a cDMARD Citation[33]. Per-capita GDP was positively correlated with access to biologics (r = 0.86), and negatively correlated with health status (r = –0.78) Citation[33]. Despite this, there is still large variation in the access to, or use of, biologic treatment in countries with similar per-capita GDP across different IMIDs, including RA, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and psoriasis Citation[34,35], suggesting that other factors, such as reimbursement, play an important role in determining access. Of note, several analyses performed in a number of different countries have shown that the high price of biologics contributes to inequalities of care, and that patients with limited access to biologics have poorer clinical outcomes Citation[25,36–38].

Role of biosimilars in reducing costs & increasing patient access to biologics: lessons from other therapy areas

Many RMP biologics have now reached, or are approaching, patent expiry. This is heralding a new era of biologic therapy in RA, thanks to the increasing development and use of biosimilar drugs. Biosimilars offer the promise of substantial savings relative to the RMP. For example, it has been estimated that Germany, France and the UK each stand to save between €2.3 billion and €11.7 billion between 2007 and 2020 in response to the introduction of biosimilars Citation[39]. These savings have the potential to be used either to increase the number of patients with access to biologics, or to be diverted into other aspects of care, such as increasing physician numbers, providing rehabilitation services, home help or transportation facilities.

Such benefits are already being demonstrated for so-called ‘first-generation’ biosimilars approved in Europe from 2006 onward, including granulocyte colony-stimulating factors (G-CSFs) Citation[40,41] and erythropoietins Citation[42–44]. Switching to biosimilar G-CSF from RMP G-CSF has been shown to markedly reduce expenditure, increase patient access and improve adherence to disease-management guidelines Citation[40,41]. In 2011 alone, annual savings from the use of biosimilar rather than RMP G-CSF amounted to €85 million across 17 European countries Citation[40].

Data are also beginning to emerge which show that cost savings can also be achieved by the adoption of biosimilars in RA. For example, a recent study in China used a discrete event stimulation model to assess the cost–effectiveness of a biosimilar of etanercept. This study showed that replacing RMP etanercept with its biosimilar was likely to be cost-effective in patients with moderately active RA Citation[45]. In the section below, we focus on information regarding the cost–effectiveness of CT-P13 in RA, as well as in other IMIDs.

Pharmacoeconomic appraisal of CT-P13: an infliximab biosimilar

CT-P13 is a biosimilar version of the TNF inhibitor infliximab that, in 2013, became the first biosimilar monoclonal antibody (mAb) to be approved by the EMA. In a multicenter, double-blind, randomized, controlled Phase III trial, CT-P13 and RMP infliximab were shown to have equivalent efficacy, as well as highly comparable safety, pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics in patients with RA Citation[46]. These data were supported by the findings of a Phase I trial in patients with ankylosing spondylitis (AS) Citation[47]. Two meta-analyses have also confirmed that CT-P13 possesses efficacy and safety profiles similar to other biologic drugs, both in RA and AS Citation[48,49]. In these analyses, CT-P13 was compared with several RMP biologics, namely infliximab, abatacept, adalimumab, certolizumab pegol, etanercept, golimumab, rituximab and tocilizumab.

In the last few years, CT-P13 has been introduced into clinical practice in an increasing number of countries. According to a recent study on the use of biologics in patients with IBD living in Central and Eastern European (where marketing of CT-P13 began in 2014), the introduction of CT-P13 has resulted in a 20–25% reduction in the price of infliximab Citation[34]. From May 2015 onward, patients in Hungary who initiate biologic therapy with infliximab must be treated with CT-P13. In addition, although a mandatory switch to CT-P13 in patients currently treated with RMP infliximab is not recommended, IBD patients in Hungary who relapse more than a year after the previous biologic therapy is stopped should only be treated with the biosimilar Citation[34]. In Poland, biologic therapy-naïve patients must be treated with the biosimilar, and patients receiving RMP are mandated to switch to CT-P13 maintenance therapy Citation[34]. Furthermore in May 2015, NICE in the UK issued a consultation on draft guidance for patients with AS and axial spondyloarthritis, which covers use of biosimilars Citation[50]. Due to the lower price of CT-P13 compared with RMP, cost savings in the National Health Service have been projected, depending on final details of the guidance adopted.

Budget impact of CT-P13 in RA

A number of different budget-impact analyses have been conducted to evaluate the cost savings that may be associated with switching from RMP infliximab to CT-P13 in patients with RA. These analyses have demonstrated that switching RA patients could lead to considerable savings and increase access to effective biologic therapy Citation[51–53].

Budget impact analysis of CT-P13 in the UK, Italy, France & Germany

The budget impact of the introduction of CT-P13 for treating RA in four Western European countries (the UK, Italy, France and Germany) has been estimated Citation[51]. In this study, three different scenarios were evaluated: discounts of 10, 20 and 30% with market uptake growth rates of 20, 30 and 40%, respectively. The market share for CT-P13 was assumed to be 25% in the first year in all three scenarios Citation[51].

Over 5 years, the total savings associated with switching patients with RA to CT-P13 were predicted to be €95.9, €233 and €433.5 million for the 10, 20 and 30% discount scenarios, respectively Citation[51]. These results are supported by another analysis – focused just on Italy – which demonstrated that the availability of CT-P13 could lead to cumulative national cost savings of €47 million over 5 years Citation[54].

Table 1. Predicted budget impact of introduction of CT-P13 for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis in the UK, Italy, France and Germany, based on three different scenarios regarding discount relative to the ‘reference medicinal product’ and percentage market uptake.

Budget impact of the introduction of CT-P13 in six Central & Eastern European countries

The budget impact of CT-P13 introduction has also been estimated for patients with RA in Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Romania and Slovakia Citation[52]. To do this, two scenarios were compared with a reference scenario, in which only the RMP was available. In the first scenario, only patients with no prior history of biologic therapy received CT-P13. In the second scenario, interchange from the RMP to CT-P13 was permitted and 80% of the patients were assumed to change.

Over 3 years, and assuming the availability of CT-P13 at a 25% discount, savings of €15.3 million could be made in the first scenario, and €20.8 million in the second . This would allow the treatment of an additional 1200 or 1800 patients across the six countries, respectively Citation[52].

Table 2. Predicted budget impact of the introduction of CT-P13 for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis in Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Romania and Slovakia based on two different scenarios over 3 years.

Budget impact analysis of the introduction of CT-P13 in Ireland

A budget impact analysis has also been conducted to evaluate the introduction of CT-P13 for patients with RA in Ireland Citation[53]. This analysis assumed the transfer of all existing RMP infliximab users to CT-P13, use of CT-P13 in new cases and that CT-P13 is available at a discount of 20% Citation[53]. Annual savings with CT-P13 were predicted to be €579,631 in year 1; €1,165,400 in year 2; €1,177,553 in year 3; €1,189,463 in year 4 and €1,201,137 in year 5. The total savings over 5 years made by the introduction of CT-P13 for RA patients would be up to €5,313,184. This amount would be enough to treat an additional 337 patients with a biosimilar for 1 year.

Budget impact of CT-P13 in other IMIDs

Budget savings have also been demonstrated with CT-P13 in IMIDs aside from RA. A budget-impact model was used to predict total savings from the introduction of CT-P13 to treat Crohn’s disease (CD) in the UK, Italy and France. Total savings over 5 years across the three countries ranged from €76 million to €336 million Citation[55]. In addition, a similar model was used to predict total savings from the introduction of CT-P13 to treat CD and ulcerative colitis in Germany, Italy, Belgium, the Netherlands and the UK. For treatment-naïve and switch patients combined, the projected net budget savings over 1 year due to the introduction of CT-P13 ranged from €0.7 million (Italy) to €17.9 million (Germany) for CD, and from €0.3 million (UK) to €6.3 M (Germany) for ulcerative colitis, depending on the discount rate applied Citation[56]. Likewise, significant savings have been predicted to be made in CD in a budget impact analysis conducted in Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Romania and Slovakia Citation[57].

Discussion

Since the introduction of the first biological DMARD (or ‘biologic’) over 15 years ago, the number of these drugs available for the treatment of IMIDs such as RA has grown considerably. Biologics have proved to be highly effective treatments for RA Citation[23,58] and have revolutionized outcomes in many patients with this often devastating condition. Indeed, a recent systematic review has confirmed the efficacy of nine RMP biologics, as well as that of the infliximab biosimilar CT-P13, for the treatment of RA Citation[22]. According to this analysis, the combination of a biologic with a cDMARD is significantly more efficacious than a cDMARD alone Citation[22]. Development of biologics has also led to an increase in the speed with which health economic analyses and health technology assessments in RA are performed Citation[59].

Biologics are complex, heterogeneous molecules and are therefore expensive to produce. Due to the high price of RMP biologics, use of these agents is generally limited to the second-line setting. Indeed, in Europe, biologics are only recommended for RA patients who fail to respond adequately to cDMARD treatment alone Citation[60]. In response to the challenges posed by the high cost of biologics in IMIDs and other areas of medicine, interest in biosimilars is on the rise. Currently, 19 biosimilars have been approved by the EMA across four different classes (the somatropins, erythropoietins, G-CSFs and mAbs). Although these biosimilars have a significant share of the biologics market in central Europe Citation[61], uptake of biosimilars could be higher elsewhere in Europe and in other parts of the world. Various reasons may account for low uptake of biosimilars, including the attitudes of physicians and patients to the use of these agents and the reimbursement conditions in different countries. In a recent Canadian study, 81 rheumatologists were surveyed to determine their attitude toward offering biosimilars as an alternative to RMP biologics Citation[62]. Only 31% of those surveyed were found to be familiar with biosimilars, while a high proportion (72%) were unlikely to offer biosimilar treatment to a biologic-naïve patient as initial therapy. The majority (88%) would be concerned if pharmacists were able to substitute an RMP biologic with its biosimilar without the knowledge of the physician Citation[62]. Another study investigated the attitudes of IBD specialists toward biosimilars. Here, 307 specialists were surveyed, with 50% of responders believing that biosimilars can bring significant reductions in healthcare costs. Of note, however, less than 10% of the specialists thought that biosimilar and RMP mAbs were interchangeable Citation[63].

In order for biosimilars to be accepted by healthcare professionals and patients, and therefore be used with confidence in the clinic, there needs to be robust evidence that they show comparable efficacy and safety to their respective RMP. In particular, increased knowledge and understanding of the long-term efficacy and safety of biosimilars is required. Two randomized controlled clinical trials have directly compared the safety and efficacy of CT-P13 and RMP infliximab in patients with RA or AS Citation[46,47]. Over the course of the 30-week, double-blind treatment phases of these trials, CT-P13 was found to be equivalent to RMP infliximab in terms of efficacy and pharmacokinetics, and highly comparable with respect to safety. The effects of longer-term CT-P13 treatment and of switching from RMP infliximab to CT-P13 were investigated in open-label extensions of the two trials that continued to week 102. No noticeable effects on safety or efficacy were observed after longer-term (i.e., 102 weeks’) treatment with CT-P13 or in patients who switched from RMP infliximab to CT-P13 treatment at week 54 Citation[64–67].

Another aspect influencing the attitude of physicians toward biosimilars is reimbursement conditions. Physicians are likely to offer patients already on biologic therapy a change to a biosimilar if the patient will benefit from the reimbursement and cost savings, and if this change resulted in a continuous medicine supply for the patient Citation[68]. Notably, lack of reimbursement strategies was the main contributor to the slow uptake of biologics in Eastern European countries and, via the adoption of such strategies, this issue has now been largely addressed.

By highlighting the comparability of biosimilars to their RMP, and the expected economic and budgetary benefits of these drugs to physicians, it is likely that uptake of biosimilars will increase in the future, both in Europe and worldwide. It is also predicted that continued development of biosimilars, and of course the increased use of these drugs, will ease the pressure on healthcare systems by providing a more cost-effective alternative to RMPs.

Conclusions

RA is a significant burden both for affected individuals and for society, and this burden will only increase as the world’s population ages. Biologic therapies have transformed treatment of RA in recent years; however, these drugs are expensive and therefore access for many patients is limited or non-existence. Biosimilar versions of RMP biologics have the potential to help address this expense and inequality. In patients with RA, CT-P13 has been shown to have equivalent efficacy and highly comparable safety to RMP infliximab Citation[46]. Forecasts suggest that substitution of CT-P13 for its RMP in various European countries could save hundreds of millions of euros, allowing more RA patients to be treated, or for funds to be diverted into other aspects of healthcare. Clinical data collected to date suggest this change could be made without compromising either efficacy or safety for patients.

Expert commentary

Biologic therapy of IMIDs such as RA is often extremely effective; however, due to the high cost of biologic drugs, many patients with RA cannot access this type of therapy. The introduction of biosimilars has offered a cost-effective alternative to the more expensive RMP biologics. Significant savings are likely to be made if eligible RA patients on RMP biologics are switched to biosimilars, or if biologic therapy-naïve patients are first offered treatment with biosimilars. These savings will allow funds to be re-directed; for example, to give other patients access to treatment. Evidence from other areas of medicine has confirmed that such predicted benefits of biosimilar adoption have been observed in ‘real-life’. However, in order to maximize savings in RA, physicians need to be educated to understand that biosimilars undergo a strict process of evaluation prior to approval; one that usually includes the performance of randomized trials in the patient population of interest. Furthermore, the budget savings that can be made via use of biosimilars, and how these savings ease the pressure on healthcare systems, need to be emphasized. Changes in reimbursement strategies in many countries may also be needed.

Five-year view

Biologics have revolutionized the treatment of RA. However, these drugs are extremely expensive and this fact has resulted in wide inequalities in their use. An increase in awareness of biosimilars, and in particular the robustness with which they are developed, is likely to increase uptake of these drugs over the coming years. As biosimilars offer a cost-effective alternative to their RMP biologics, their increased uptake will drive significant savings. The savings made will enable more patients to access biologic therapy and thus current treatment inequalities will begin to dissipate. Savings may also be diverted to other aspects of care and therefore help combat the increasing pressure on general healthcare budgets in Europe and worldwide. The expiry of further biologic drug patents in the next few years will generate interest in the development of new biosimilars, as well as stimulate the development of novel therapeutics for the treatment of IMIDs.

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a debilitating disease that leads to increasing levels of disability in working-age patients.

The economic burden of RA is high and results in huge pressure on healthcare systems, as well as on patients and their families.

Biologic drugs have revolutionized the treatment of RA and are highly effective. However, because of their complex nature, these drugs are extremely expensive compared with ‘synthetic’ or ‘conventional’ disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (cDMARDs).

Cost–effectiveness analyses have shown biologics to be cost-effective as second-line therapy in combination with cDMARDs in RA patients who have not adequately responded to cDMARD therapy alone.

In recent years, interest in so-called ‘biosimilar’ drugs has risen. Biosimilars are highly comparable to ‘reference medicinal product’ (RMP) biologics in terms of their efficacy and safety profiles. A key advantage of biosimilars over RMPs is their lower cost.

Studies have estimated huge savings to be made through the introduction of biosimilars into the RA setting. Significant savings can be made both from switching patients already on an RMP to biosimilar treatment, as well as from offering biosimilars to biologic therapy-naïve patients.

Such savings are likely to result in an increase in the number of patients with access to biologic therapy, thereby easing the inequalities that have arisen due to the high cost of RMP biologics. Savings may also be diverted to other aspects of care and thereby ease pressure on healthcare system budgets in general.

Acknowledgements

Editorial support (writing assistance, assembling tables and figures, collating author comments, grammatical editing and referencing) was provided by Ryan Woodrow (Aspire Scientific Limited, Bollington, UK) and was funded by Celltrion Healthcare Co., Ltd (Incheon, Republic of Korea).

Financial & competing interests disclosure

L Gulácsi has been paid as a consultant by Celltrion and received funding and support for research on biosimilars from EGIS Pharma, the distributor of CT-P13 in Hungary. M Péntek, P Baji and V Brodszky have received funding and support for research on biosimilars from EGIS Pharma, the distributor of CT-P13 in Hungary. HU Kim, SY Kim and YY Cho are full-time employees of Celltrion. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

Notes

References

- Cross M, Smith E, Hoy D, et al. The global burden of rheumatoid arthritis: estimates from the global burden of disease 2010 study. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:1316-22

- Ollier WE, Harrison B, Symmons D. What is the natural history of rheumatoid arthritis? Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2001;15:27-48

- McInnes IB, O’Dell JR. State-of-the-art: rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2010;69:1898-906

- Furneri G, Mantovani LG, Belisari A, et al. Systematic literature review on economic implications and pharmacoeconomic issues of rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2012;30:S72-84

- Gabriel SE. Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in rheumatoid arthritis. Am J Med 2008;121:S9-14

- Lundkvist J, Kastang F, Kobelt G. The burden of rheumatoid arthritis and access to treatment: health burden and costs. Eur J Health Econ 2008;8(Suppl 2):S49-60

- Orlewska E, Ancuta I, Anic B, et al. Access to biologic treatment for rheumatoid arthritis in Central and Eastern European (CEE) countries. Med Sci Monit 2011;17:SR1-13

- World Health Organization. Expert Committee on Biological Standardization. Geneva, 19 to 23 October 2009. Guidelines on evaluation of similar biotherapeutic products (SBPs). Available from: www.who.int/biologicals/areas/biological_therapeutics/BIOTHERAPEUTICS_FOR_WEB_22APRIL2010.pdf [Last accessed 28 July 2015]

- Pentek M, Kobelt G, Czirjak L, et al. Costs of rheumatoid arthritis in Hungary. J Rheumatol 2007;34:1437

- Pentek M, Szekanecz Z, Czirjak L, et al. Impact of disease progression on health status, quality of life and costs in rheumatoid arthritis in Hungary. Orv Hetil 2008;149:733-41

- Bruce B, Fries JF. The Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ). Clin Exp Rheumatol 2005;23:S14-18

- Ma VY, Chan L, Carruthers KJ. Incidence, prevalence, costs, and impact on disability of common conditions requiring rehabilitation in the United States: stroke, spinal cord injury, traumatic brain injury, multiple sclerosis, osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, limb loss, and back pain. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2014;95:986-95

- Sullivan PW, Ghushchyan V, Huang XY, et al. Influence of rheumatoid arthritis on employment, function, and productivity in a nationally representative sample in the United States. J Rheumatol 2010;37:544-9

- Burton W, Morrison A, Maclean R, et al. Systematic review of studies of productivity loss due to rheumatoid arthritis. Occup Med (Lond) 2006;56:18-27

- Eberhardt K, Larsson BM, Nived K, et al. Work disability in rheumatoid arthritis–development over 15 years and evaluation of predictive factors over time. J Rheumatol 2007;34:481-7

- Birnbaum H, Pike C, Kaufman R, et al. Societal cost of rheumatoid arthritis patients in the US. Curr Med Res Opin 2010;26:77-90

- Maetzel A, Li LC, Pencharz J, et al. The economic burden associated with osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, and hypertension: a comparative study. Ann Rheum Dis 2004;63:395-401

- Benucci M, Saviola G, Manfredi M, et al. Cost effectiveness analysis of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs in rheumatoid arthritis. A systematic review literature. Int J Rheumatol 2011;2011:845496

- Horvath CZ, Sebestyen A, Osterle A, et al. Economic burden of long-term care of rheumatoid arthritis patients in Hungary. Eur J Health Econ 2014;15(Suppl 1):S131-5

- Krol M, Papenburg J, van Exel J. Does including informal care in economic evaluations matter? A systematic review of inclusion and impact of informal care in cost-effectiveness studies. Pharmacoeconomics 2015;33:123-35

- Kawatkar AA, Jacobsen SJ, Levy GD, et al. Direct medical expenditure associated with rheumatoid arthritis in a nationally representative sample from the medical expenditure panel survey. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2012;64:1649-56

- Nam JL, Ramiro S, Gaujoux-Viala C, et al. Efficacy of biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: a systematic literature review informing the 2013 update of the EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:516-28

- St Clair EW, van der Heijde DM, Smolen JS, et al. Combination of infliximab and methotrexate therapy for early rheumatoid arthritis: a randomized, controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum 2004;50:3432-43

- Kuek A, Hazleman BL, Ostor AJ. Immune-mediated inflammatory diseases (IMIDs) and biologic therapy: a medical revolution. Postgrad Med J 2007;83:251-60

- Fischer MA, Polinski JM, Servi AD, et al. Prior authorization for biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: a description of US Medicaid programs. Arthritis Rheum 2008;59:1611-17

- Modena V, Bianchi G, Roccatello D. Cost-effectiveness of biologic treatment for rheumatoid arthritis in clinical practice: an achievable target? Autoimmun Rev 2013;12:835-8

- Nurmohamed MT, Dijkmans BA. Efficacy, tolerability and cost effectiveness of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs and biologic agents in rheumatoid arthritis. Drugs 2005;65:661-94

- Dorner T, Strand V, Castaneda-Hernandez G, et al. The role of biosimilars in the treatment of rheumatic diseases. Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72:322-8

- Yoo DH. The rise of biosimilars: potential benefits and drawbacks in rheumatoid arthritis. Expert Rev Clin Immunol 2014;10:981-3

- van der Velde G, Pham B, Machado M, et al. Cost-effectiveness of biologic response modifiers compared to disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs for rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2011;63:65-78

- Gulacsi L, Rencz F, Pentek M, et al. Transferability of results of cost utility analyses for biologicals in inflammatory conditions for Central and Eastern European countries. Eur J Health Econ 2014;15(Suppl 1):S27-34

- Joensuu JT, Huoponen S, Aaltonen KJ, et al. The cost-effectiveness of biologics for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review. PLoS ONE 2015;10:e0119683

- Putrik P, Ramiro S, Kvien TK, et al. Inequities in access to biologic and synthetic DMARDs across 46 European countries. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:198-206

- Rencz F, Pentek M, Bortlik M, et al. Biological therapy in inflammatory bowel diseases: access in Central and Eastern Europe. World J Gastroenterol 2015;21:1728-37

- Rencz F, Kemeny L, Gajdacsi J, et al. Use of biologics for psoriasis in Central and Eastern European countries. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2015; In Press

- Pease C, Pope JE, Truong D, et al. Comparison of anti-TNF treatment initiation in rheumatoid arthritis databases demonstrates wide country variability in patient parameters at initiation of anti-TNF therapy. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2011;41:81-9

- Sokka T, Kautiainen H, Pincus T, et al. Disparities in rheumatoid arthritis disease activity according to gross domestic product in 25 countries in the QUEST-RA database. Ann Rheum Dis 2009;68:1666-72

- Desai RJ, Rao JK, Hansen RA, et al. Predictors of treatment initiation with tumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibitors in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Manag Care Pharm 2014;20:1110-20

- Haustein R, de Millas C, Hoer A, et al. Saving money in the European healthcare systems with biosimilars. Generics and Biosimilars Initiative Journal 2012;1:120-6

- Gascon P, Tesch H, Verpoort K, et al. Clinical experience with Zarzio(R) in Europe: what have we learned? Support Care Cancer 2013;21:2925-32

- Verpoort K, Mohler TM. A non-interventional study of biosimilar granulocyte colony-stimulating factor as prophylaxis for chemotherapy-induced neutropenia in a community oncology centre. Ther Adv Med Oncol 2012;4:289-93

- Lapadula G, Ferraccioli GF. Biosimilars in rheumatology: pharmacological and pharmacoeconomic issues. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2012;30:S102-6

- Abraham I, Han L, Sun D, et al. Cost savings from anemia management with biosimilar epoetin alfa and increased access to targeted antineoplastic treatment: a simulation for the EU G5 countries. Future Oncol 2014;10:1599-609

- Horbrand F, Rottenkolber D, Fischaleck J, et al. Erythropoietin-induced treatment costs in patients suffering from renal anemia - a comparison between biosimilar and originator drugs. Gesundheitswesen 2014;76:e79-84

- Wu B, Song Y, Leng L, et al. Treatment of moderate rheumatoid arthritis with different strategies in a health resource-limited setting: a cost-effectiveness analysis in the era of biosimilars. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2015;33:20-6

- Yoo DH, Hrycaj P, Miranda P, et al. A randomised, double-blind, parallel-group study to demonstrate equivalence in efficacy and safety of CT-P13 compared with innovator infliximab when coadministered with methotrexate in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis: the PLANETRA study. Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72:1613-20

- Park W, Hrycaj P, Jeka S, et al. A randomised, double-blind, multicentre, parallel-group, prospective study comparing the pharmacokinetics, safety, and efficacy of CT-P13 and innovator infliximab in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: the PLANETAS study. Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72:1605-12

- Baji P, Pentek M, Szanto S, et al. Comparative efficacy and safety of biosimilar infliximab and other biological treatments in ankylosing spondylitis: systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Eur J Health Econ 2014;15(Suppl 1):S45-52

- Baji P, Pentek M, Czirjak L, et al. Efficacy and safety of infliximab-biosimilar compared to other biological drugs in rheumatoid arthritis: a mixed treatment comparison. Eur J Health Econ 2014;15(Suppl 1):S53-64

- NICE. Draft guidance for consultation: Ankylosing spondylitis and axial spondyloarthritis (non-radiographic) - adalimumab, etanercept infliximab and golimumab (inc rev TA143 and TA233) ID694. Available from: www.nice.org.uk/guidance/indevelopment/gid-tag355 2015. [Last accessed 24 June 2015]

- Kim J, Hong J, Kudrin A. 5 year budget impact analysis of biosimilar infliximab for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis in UK, Italy, France and Germany. Arthritis Rheumatol 2014;11(Suppl):S512 (abstract 1166)

- Brodszky V, Baji P, Balogh O, Pentek M. Budget impact analysis of biosimilar infliximab (CT-P13) for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis in six Central and Eastern European countries. Eur J Health Econ 2014;15(Suppl 1):S65-71

- McCarthy G, Ebel BC, Guy H. Introduction of an infliximab biosimilar (CT-P13): A five-year budget impact analysis for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis in Ireland. Value Health 2013;16:A558 (PMS22)

- Lucioni C, Mazzi S, Caporali R. Budget impact analysis of infliximab biosimilar: the Italian scenery. Global & Regional Health Technology Assessment 2015:Advanced online publication

- Kim J, An Hong J, Kudrin A. 5 year budget impact analysis of CT-P13 (infliximab) for the treatment of Crohn’s disease in UK, Italy and France. J Crohns Colitis 2015;9(Suppl 1):S144 (P137)

- Jha A, Dunlop W, Upton A. Budget impact analysis of introducing biosimilar infliximab for the treatment of gastro intestinal disorders in five European countries. J Crohns Colitis 2015;9(Suppl 1):S427 (P691)

- Brodszky N, Rencz F, Pentek M, et al. A budget impact model for biosimilar infliximab in Crohn’s disease in Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Romania and Slovakia. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res 2015. [Epub ahead of print]

- Maini RN, Breedveld FC, Kalden JR, et al. Therapeutic efficacy of multiple intravenous infusions of anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha monoclonal antibody combined with low-dose weekly methotrexate in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1998;41:1552-63

- Gulacsi L. Biological and biosimilar therapies in inflammatory conditions: challenges for the Central and Eastern European countries. Eur J Health Econ 2014;15(Suppl 1):S1-4

- Smolen JS, Landewe R, Breedveld FC, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2013 update. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:492-509

- Grabowski H, Guha R, Salgado M. Biosimilar competition: lessons from Europe. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2014;13:99-100

- Grabowski D, Henderson B, Lam D, et al. Attitudes towards subsequent entry biologics/biosimilars: A survey of Canadian rheumatologists. Clin Rheumatol 2015. [Epub ahead of print]

- Danese S, Fiorino G, Michetti P. Viewpoint: knowledge and viewpoints on biosimilar monoclonal antibodies among members of the European Crohn’s and Colitis Organization. J Crohns Colitis 2014;8:1548-50

- Park W, Jaworski J, Brzezicki J, et al. A randomised, double-blind, parallel-group, phase 1 study comparing the pharmacokinetics, safety and efficacy of CT-P13 and infliximab in patients with active ankylosing spondylitis: 54 week results from the PLANETAS study. Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72(Suppl 3):516 [FRI0421]

- Yoo DH, Racewicz A, Brzezicki J, et al. A phase 3 randomised controlled trial to compare CT-P13 with infliximab in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis: 54 week results from the PLANETRA study. Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72(Suppl 3):73 [OP0068]

- Yoo DH, Prodanovic N, Jaworski J, et al. Efficacy and safety of CT-P13 (infliximab biosimilar) over two years in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: comparison between continued CT-P13 and switching from infliximab to CT-P13. Arthritis Rheum 2013;65:3319 (L1)

- Park W, Miranda P, Brzosko M, et al. Efficacy and safety of CT-P13 (infliximab biosimilar) over two years in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: comparison between continuing with CT-P13 and switching from infliximab to CT-P13. Arthritis Rheum 2013;65:3326 (L15)

- Baji P, Gulacsi L, Lovasz D, et al. Treatment preferences of originator versus biosimilar drugs in Crohn’s disease; discrete choice experiment among gastroenterologists. Scand J Gastroenterol 2015. [Epub ahead of print]

- Brodszky V, Bálint P, Géher P, et al. Disease burden of psoriatic arthritis compared to rheumatoid arthritis, Hungarian experiment. Rheumatol Int 2009;30:199-205