Abstract

The role of inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) as rescue medication for asthma exacerbations in children is controversial. ICS have the important potential advantage of direct delivery to the airways, which substantially reduces the risk of the adverse systemic effects that may be associated with oral corticosteroids. Oral corticosteroids are still prefered for severe attacks. Five randomized, controlled studies performed at home and six performed in the emergency department indicated that ICS are at least as effective as the oral route. Our pediatric out-patient asthma clinic has been using ICS for asthma exacerbations for more than 25 years. The key elements to success are the administration of repetitive doses at least four-times higher than the maintenance dose and parental adherence to the treatment plan. This article reviews the findings in the literature favoring this approach and describes our methodology in detail.

Current international guidelines, such as the Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) Citation[1] and the Expert Panel Report (EPR)-3 Citation[2], in addition to the 2008 Practical Allergy consensus report (PRACTALL) Citation[3], have only recently begun to include children under 5 years of age in their recommendations for asthma control. These international guidelines and consensus reports recommend the early use of oral corticosteroids, in addition to oxygen and β2-agonists, for the control of asthma exacerbations. Nevertheless, several recent reviews have presented evidence of the effectiveness and safety of inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) in both adults Citation[4] and children Citation[5,6]. Oral corticosteroids have been proven to be effective in children with asthma; they are less expensive than ICS and are more convenient for use in children, who can tolerate several days of treatment with this modality Citation[7]. However, even short intermittent courses can cause adverse clinical effects Citation[8]. ICS, at conventional doses, avoid this problem Citation[9], mainly because the drug is delivered directly to the lung and enters into the body in lower concentrations Citation[10]. Unlike oral corticosteroids, they are not associated with a decrease in serum cortisol concentrations Citation[11–13] and they may enhance the local and systemic effect of β2-agonists Citation[14]. Even in relatively high doses, ICS are metabolically safe for use in children Citation[7,11–13]. In studies of asthmatic children treated with inhaled budesonide, there was no change in plasma cortisol concentrations, either fasting at 8 a.m. or 1 h after adrenocorticotropic hormone stimulation Citation[8], and there were no adverse effects of relatively high doses on the diurnal variation of serum cortisol levels Citation[9]. De Benedictis et al. reported that 10 days’ administration of nebulized budesonide 500 µg or fluticasone 250 µg did not suppress the hypothalamic–pituitary axis Citation[13].

The rapid action of ICS, starting within the first hour of administration Citation[8], may be attributable to their nongenomic effect Citation[4,15–17], as opposed to the action of oral corticosteroids, which involves genomic transcription. The vasoconstriction induced by ICS is transitory; therefore, the improved clinical response may be explained by the direct effect of the inhaled drug on the mucosal blood vessels, in addition to its effects on plasma exudation and bronchial secretion Citation[17]. Furthermore, the decrease in airway blood flow is likely to enhance the action of inhaled bronchodilators by diminishing their clearance from the airway Citation[18]. Thus, simultaneous administration of ICS and β2-agonists could be of clinical significance.

The present article investigates the evidence for the effectiveness of ICS as rescue medication in asthma exacerbations in children. In almost all of the studies presented, inhaled β2-agonists were given before the administration of ICS. The data were derived from a comprehensive Medline search, assisted by a library information expert at a university medical center, and included studies conducted at the allergy clinic of the same center over the last 25 yearsg.

ICS for the treatment of asthma exacerbations at home

The literature search yielded five randomized, controlled studies Citation[19–24] and two uncontrolled studies Citation[24,25] of children with asthma who were treated at home with ICS. All showed that ICS were effective at controlling wheezing and asthma exacerbations. In all cases, the ICS were administered either at the first sign of an upper-respiratory tract infection Citation[19,20], at the onset of virus-induced symptoms of asthma Citation[21] or at the first sign of an asthma exacerbation Citation[22,23].

Connett and Lenney reported that treatment with inhaled budesonide 800 or 1600 µg twice daily significantly decreased daytime and night-time wheezing in preschool children Citation[19]. The parents reported a preference for budesonide over placebo. Svedmyr et al. showed that treatment with inhaled budesonide by Turbohaler®, 200 µg four-times daily for 3 days, followed by three-times daily for 3 days and then twice daily for 3 days, reduced asthma symptoms in toddlers with episodic asthma Citation[20]. Accordingly, in the study of Wilson and Silverman, symptom scores were significantly lower during treatment with inhaled beclometasone 750 µg, administered three-times daily for 5 days, than for placebo, with a significantly higher peak flow during active treatment Citation[21]. More recently, Volovitz et al. showed that high starting doses of either budesonide (1600 µg) or fluticasone (1000 µg), followed by a gradual decrease in dose over 4–8 days, controlled 86% of 237 asthma exacerbations in preschool children Citation[22]. None of the patients required oral corticosteroids. In the mildest cases, just doubling the maintenance dose was effective. Mannan et al. treated asthmatic children aged 2–7 years with increased doses of ICS for 12 days, starting early in the course of the exacerbation Citation[23]. They reported that this protocol prevented the worsening of symptoms that would otherwise have required treatment with systemic corticosteroids. There was no significant difference between the patients treated with twice (n = 23), four-times (n = 43) or eight-times (n = 83) their maintenance dose of ICS. In an open-label study in young children, Nuhoglu et al. reported that 1600 µg/day of inhaled budesonide delivered by Turbohaler was more effective in decreasing the pulmonary index score than budesonide 800 µg/day combined with oral methylprednisone 1 mg/kg/day Citation[24]. Using a similar design, Volovitz et al. found that in children treated with budesonide 200–400 µg four-times daily at the first signs of an asthma exacerbation, followed by a gradual decrease in dose over 4–8 days, 94% of the 1061 asthma exacerbations were well controlled, with almost no need for oral corticosteroid therapy or hospitalization Citation[25].

In a Cochrane review, McKean and Ducharme concluded that in randomized controlled trials of corticosteroid treatment versus placebo, episodic high doses of ICS were a partially effective strategy for the treatment of mild episodic viral wheeze of childhood Citation[26]. Unfortunately, there are no published studies comparing the use of oral corticosteroids with ICS at home in children with asthma exacerbations.

ICS for the treatment of asthma exacerbation in the emergency department

Overall, eight randomized, controlled studies have been performed on the use of ICS to control asthma in children in the emergency department Citation[8,27–33]. The methodological quality was high, validating the conclusions of this article. When pooled, the results suggested that ICS are effective in controlling most acute asthma exacerbations in this setting.

Six of the eight studies were double-blind trials comparing ICS to oral prednisone 2 mg/kg Citation[8,27–31]. One study compared ICS to placebo Citation[32] and one investigated the addition of ICS to oral corticosteroids Citation[33]. In all of them, the children were also treated with β2-agonists and, when necessary, oxygen, and the doses of ICS were at least four-times the maintenance dose. It is noteworthy that the latest GINA Citation[102], which recommends systemic corticosteroids for the treatment of asthma exacerbations, also includes ICS at four-times the maintenance dose as an effective option.

Scarfone et al. compared the effectiveness of a single dose of nebulized dexamethasone 2000 µg/kg with oral prednisone 2 mg/kg for controlling asthma in the emergency department in 111 children aged 1–17 years Citation[27]. They found that the nebulized dexamethasone group was significantly more ready for discharge at 2 h from presentation. Volovitz et al. allocated children aged 6–16 years to receive one dose of budesonide 1600 µg by Turbohaler or prednisone 2 mg/kg, followed by a rapid reduction in dose over the next few days Citation[8]. In both groups, there was a rapid, hour-by-hour decrease in the pulmonary index score in the first 4 h after treatment. However, oral corticosteroids were associated with a decrease in serum cortisol concentration, whereas ICS were not. In a study of 80 children, Devidayal et al. reported that three doses of nebulized budesonide 800 µg given at half-hourly intervals resulted in a significantly better improvement in oxygen saturation, respiratory rate, pulmonary index and respiratory distress score compared with prednisone Citation[29]. The children treated with nebulized budesonide were also discharged significantly earlier. In the study of Matthews et al. of 46 children, treatment with nebulized budesonide 2000 µg over 8 h was associated with a significantly greater improvement in forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) than treatment with oral prednisone Citation[28]. Accordingly, in a larger study of 321 children, Manjra et al. found that treatment with nebulized fluticasone 1000 µg twice daily during asthma exacerbations, resulted in similar symptom scores to treatment with oral corticosteroids, but better peak expiratory flow values Citation[30]. In a study of 49 children aged 2–7 years, Milani et al. reported equally good results for a single dose of nebulized budesonide 2000 µg and oral prednisone 2 mg/kg in improving symptom severity Citation[31]. Similar findings were observed when ICS were compared with placebo Citation[32] or added to oral corticosteroids Citation[33]. Songhai et al. administered three doses of budesonide 400 µg by holding chamber at half-hourly intervals and noted greater improvement in lung function tests and respiratory distress score, and less need for oxygen than the placebo group Citation[32]. None of the budesonide-treated children were hospitalized, compared with 23% of the placebo group. Sung et al. compared the addition of a single dose of budesonide inhalation suspension by mobilization 2000 µg, or placebo, to 1 mg/kg oral prednisone, and found that the budesonide-treated patients were released from the emergency department significantly sooner Citation[33].

In a Cochrane review of four studies in adult patients and three in children, Edmonds and Camargo suggested that the early use of ICS in acute asthma exacerbations reduces hospital admissions and improves pulmonary function compared with placebo Citation[34].

There are two double-blind, randomized studies, both by the same group, in which oral corticosteroids were found to be superior to ICS in children with asthma Citation[35,36]. In the first study, 31% of the children treated with a single dose of inhaled fluticasone 2000 µg were hospitalized, compared with 10% of the prednisone group. In addition, the children treated with prednisone had a significantly greater reduction in FEV1 from baseline to 4 h Citation[35]. In the second study, the authors noted better transient results on lung function tests in children treated with oral prednisone (28% change in FEV1) than in children treated with fluticasone by metered dose inhaler and holding chamber (19.1% change in FEV1) Citation[36]. However, the respective mean baseline FEV1 values in the ICS and oral corticosteroid groups were 46.3 and 43.9% of the predicted value in the first study Citation[35], and 63.0 and 61.5% of the predicted value in the second study Citation[36]. It is well recognized that the greater the airway restriction in children with asthma, the harder it is for the inhaled drug to enter the alveoli.

ICS for the treatment of asthma exacerbations in the hospital

We found only two studies of children with asthma exacerbations who were treated with high-dose ICS during hospitalization Citation[37,38]. Using a double-blind, parallel-group, placebo-controlled design, Daugbjerg et al. investigated the outcome of 123 children aged 1.5–18 months, hospitalized for an acute exacerbation of asthma Citation[37]. The children were randomized to one of four groups: inhaled β2-agonist alone; inhaled β2-agonists with oral prednisone; inhaled β2-agonists with nebulized budesonide (500 µg every 4 h for 5 days); and placebo. There was a higher frequency of treatment failure in the placebo group. The nebulized budesonide group had significantly better symptom scores than the oral prednisone group, and both the inhaled and oral corticosteroid groups had significantly better results than the placebo group and the β2-agonist-only group. In a prospective study, Sano et al. compared the effect of the addition of nebulized budesonide 2500 µg every 6 h with nebulized ipratropium bromide 0.1 mg every 6 h to the normal treatment regimen in 71 children with asthma exacerbations aged 3–24 months Citation[38]. The children who received inhaled budesonide improved significantly faster and their hospitalization period was significantly shorter.

Optimal control of asthma exacerbations with ICS

As noted, international guidelines and consensuses recommend the early use of oral corticosteroids, in addition to oxygen and β2-agonists, for the control of asthma exacerbation Citation[1–3]. In a review of the effectiveness of systemic corticosteroids, Rachelefsky et al. concluded that they should be used when considerable constriction of the airways is suspected Citation[7], which prevents oxygen from entering the lung. In all other circumstances, ICS may be a good choice.

The out-patient pediatric asthma clinic of Schneider Children’s Medical Center of Israel, which treats 600–800 new patients annually, has used ICS almost exclusively for the last 25 years for the treatment of mild-to-moderate exacerbations of asthma in children . The clinical results have been excellent Citation[5,6,8,11,12,22,25,39]. We define asthma exacerbations according to the GINA guidelines as ‘a sudden, progressive increase in asthma symptoms: shortness of breath, cough, wheezing and chest tightness, alone or in combination’ Citation[101]. Asthma exacerbations due to viral respiratory infections in young children are considered to be the same disease as asthma exacerbations in older children, and are treated in a similar manner. Accordingly, the GINA guidelines recommend that ‘treatment of an infectious exacerbation follows the same principles as treatment of other asthma exacerbations, that is, rapid-acting inhaled β2-agonists and early introduction of oral glucocorticosteroids or increases in inhaled glucocorticosteroids by at least fourfold.’ Citation[102].

Our clinical experience with inhaled budesonide has been described in various publications Citation[8,12,22,25,39]. We found that when parents administered early, high starting dosages of budesonide to children aged 1–14 years, they were able to control 1001 of the 1061 asthma exacerbations at home Citation[25]. Using a randomized design, we investigated children aged 6 months to 5 years with asthma exacerbations that did not respond to β2-agonists and would otherwise have been treated with oral corticosteroids. We found that treatment with high starting doses of either budesonide (1600 µg) or fluticasone (1000 µg), followed by a rapid stepwise decrease in dose over 4–8 days, successfully controlled 86% of 237 asthma exacerbations Citation[22]. In this study, even just doubling the dose in the mildest cases was also effective. By contrast, other studies claimed that simply doubling the dose was not effective in controlling asthma exacerbations. These included one study by Garrett et al.of 18 pairs of exacerbations in children (possibility of type II error) Citation[40] and two studies in adults Citation[41,42], numbering 390 and 290 subjects, respectively. We also found that treating moderately severe asthma with high doses of ICS in the emergency department yielded equally good results to oral corticosteroids for all parameters evaluated (spirometry, pulmonary indices, wheezing, accessory muscle use and oxygen saturation) Citation[8]. Furthermore, during the first week after discharge, symptoms scores improved more quickly in the ICS group Citation[8].

The excellent outcome of children treated at our pediatric clinic is attributed to three key elements of our program:

• Asthma education for the parents in recognizing the early signs of asthma exacerbations, adhering to the treatment plan and applying the correct technique of drug delivery;

• Rapid administration of ICS at home, at the first signs of asthma exacerbation;

• Starting treatment with repetitive doses of ICS at least four-times higher than the maintenance dose, followed by a gradual decrease in dose over the next few days .

The treatment of children with ICS requires a dedicated effort by the asthma clinic to impart to the parents the skills necessary to administer the drug using an inhaler and spacer. In particular, holding the mask of the spacer over the face of a child is very difficult. Our asthma clinic routinely offers parents educational sessions in which we explain the underlying mechanisms of asthma, outline the early signs of an attack, describe the general treatment plans and offer ‘hands-on’ training in drug administration. Information is provided by individual counseling, written material and targeted internet sites (the one used in our clinic is www.volovitz.co.il Citation[103]). In addition, for each individual patient, the physician formulates a detailed asthma-management plan, including information regarding the drug to be used and the frequency of its administration, taking the health-related beliefs and attitudes of the parents into account. In cases of treatment failure, before considering a change in the plan, the physician checks the integrity of the drug-delivery device and questions the parents to make sure it was filled with the drug during treatment and used properly. A follow-up visit is scheduled, and the parents are encouraged to contact the physician in the event of additional problems.

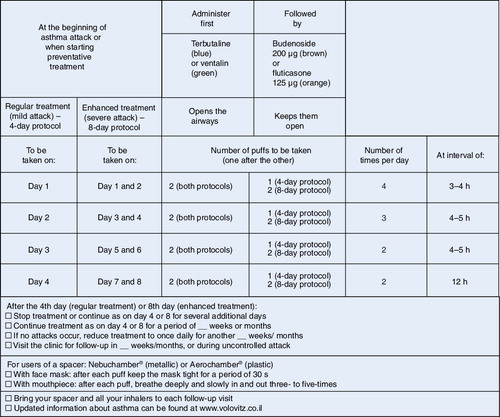

We employ three general protocols for the control of asthma exacerbations with ICS, mainly budesonide delivered by holding chamber Citation[8,12,22,25,39]:

• A 4-day protocol is used for children starting treatment with ICS and for children with relatively mild exacerbations. We encourage the parents to start the protocol at the first signs of an asthma exacerbation (usually coughing in the early stages of the common cold with runny nose). Children under 1 year of age are started at higher doses, using the 8-day protocol;

• An 8-day protocol is used for children who do not respond to treatment with the 4-day protocol and for children with moderate-to-severe exacerbations, with more significant cough, dyspnea or wheezing. We advise parents of children under 1 year of age with severe exacerbations to present to the emergency department for oxygen, because the administration of β2-agonists alone in this age group could worsen the hypoxemia;

• An 8-day plus azithromycin or doxycycline protocol is used for children who do not respond to the standard 8-day protocol and for children in whom infection with an atypical agent is suspected.

In all three protocols, children are asked to drink or to rinse their mouths after two puffs of inhaled budesonide to prevent thrush. In all three protocols, β2-agonists are administered in the first 2–4 days of treatment. In the third protocol, the rationale underlying the addition of azithromycin or doxycycline is based on growing evidence of the key role of atypical respiratory agents, such as Chlamydia pneumoniae and Mycoplasma pneumoniae, in the pathogenesis of asthma exacerbations Citation[43]. Routine antibiotic treatment has shown only a very limited benefit in asthma. However, azithromycin and doxycycline, in addition to their action on atypical respiratory pathogens, exert an anti-inflammatory effect and, at least for azithromycin, an anti-allergenic effect Citation[44]. In a recent study, we showed that in 95% of the children who did not respond to our 8-day protocol, and in children with a suspected infection with an atypical agent, the addition of azithromycin to ICS successfully controlled asthma exacerbations Citation[22].

In older children, we use a combination of an inhaled corticosteroid and a long-acting β2-agonist (Symbicort®). The Symbicort Maintenance and Reliever Therapy (SMART) approach, whereby patients increase the dose of Symbicort during worsening of symptoms, has yielded good results in adults Citation[45]. Accordingly, a recent study of 341 children with asthma showed that the approach was associated with a significant decrease in the number of days of asthma exacerbation Citation[46].

On the basis of the findings in the literature to date and our own clinical experience, we suggest that oral corticosteroids should be given to children with severe asthma exacerbation or when ICS are not available. Otherwise, a starting dose of ICS, either budesonide or fluticasone, at least four-times higher than the maintenance dose should be administered repetitively at the onset of symptoms, followed by a gradual decrease in dose over the next few days. ICS have been shown to be at least as effective as oral corticosteroids as rescue medication for mild-to-moderate asthma exacerbations in children, without the side effects associated with the oral route.

Expert commentary

International guidelines and a consensus report recommend the use of oral corticosteroids as rescue medication for asthma exacerbations in children. However, a growing body of evidence indicates that ICS are at least as effective in controlling most asthma exacerbations. Oral corticosteroids, which are less expensive and easier to use, are still recommended for severe asthma exacerbations in which penetration of the inhaled drug could be blocked by severe airway restriction. The advantages of ICS include rapid action, low concentration and, in conventional doses, absence of adverse effects. The issue remains controversial because physicians in the USA are clinically unfamiliar with budesonide metered dose inhalers with a holding chamber, which have been used at our out-patient asthma clinic for the last 25 years as rescue medication for asthma exacerbations in children. We consider exacerbations of asthma symptoms in young children under the age of 3 years with a respiratory viral infection as the same disease as asthma exacerbations in older children. Our treatment schedule is based on the repetitive administration of high doses of the inhaled drug – at least four-times the maintenance dose – followed by a gradual reduction in dose over a few days. Parental adherence to treatment is a key factor for success. This article has outlined the literature favoring the use of ICS for the early treatment of asthma exacerbation attacks in young children, at home and in the emergency setting, and describes our experience in detail.

Five-year view

International guidelines and a consensus report have only recently begun to include children under 5 years of age in their recommendations for asthma control (GINA 2008, EPR-3 2008 and PRACTALL 2008). Unfortunately, they still leave many questions unanswered because the evidence-based data are sparse. Even their definition of asthma fails to reflect contemporary changes in the concept of the disease in young children. The concept of asthma in the young pediatric group is changing and we expect that within 5 years the disease will be redefined within the medical community worldwide. The diagnosis of asthma is difficult, especially in young babies with congenital anomalies, which are sometimes associated with wheezing and cough; in infants and toddlers, the most important differential diagnosis is a foreign body, although this occurs much more rarely than asthma. At our clinic, we suspect asthma in a child with a prolonged cough (more than 3–4 weeks) that cannot be traced to another source and that responds completely to anti-asthma treatment. The diagnosis is also suspected in a child with a history of cough who presents with a wheezing episode that responds to anti-asthma medication and a child who coughs for more than 1 week after every viral respiratory infection. This type of ‘asthma of children’ is expected to disappear by 3–5 years of age.

Treatment of asthma in young children at our clinic consists of ICS at each exacerbation. However, if the exacerbations recur frequently (at less than 3-week intervals), we administer preventive treatment with ICS until the symptoms disappear. Large-scale, well-designed studies are still needed to unequivocally establish the use ICS as rescue medication for asthma exacerbations in children and to determine the optimal doses, schedules and delivery techniques. We trust that, parallel to this development, physicians will recognize the importance of parental instruction and training in identifying the early signs of an asthma exacerbation in their child and properly administering the inhaled drug. This will help ensure the success of the treatment.

Table 1. Comparison of inhaled corticosteroids and oral prednisone 2 mg/kg for the treatment of acute asthma in children in the emergency department.

Key issues

• In children with previously diagnosed asthma, signs of upper-respiratory infection should be considered signs of an asthma exacerbation.

• Viral-induced asthma exacerbations in young children should be treated in the same way as asthma exacerbations in older children.

• Parents should be taught to start treatment of asthma exacerbations at home.

• Asthma attack, acute asthma and asthma episode are the other names for asthma exacerbation.

• Asthma exacerbations should be treated with β2-agonists and corticosteroids, and oxygen when needed.

• Mild and moderate asthma exacerbations in children can be treated effectively with high doses of inhaled corticosteroids (at least four-times the maintenance dose), given repetitively for a few days until symptoms stop.

• Severe asthma exacerbations should be treated with oral corticosteroids.

• Asthma attacks, if properly treated, should be controlled within a few days. In cases of failure, the integrity of the inhaler and spacer, and the adherence of the parents to the drug treatment, should be evaluated before changing the treatment instructions.

• Children who have repeated asthma exacerbations (more than once monthly) should be treated with continuous preventive asthma medication.

• In order to succeed in treatment, parents must learn to recognize the first signs of an asthma exacerbation, follow the prescribed asthma treatment plan and use the proper drug-delivery technique.

Financial & competing interests disclosure

The author has no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

References

- Bateman ED, Hurd SS, Barnes PJ et al. Global strategy for asthma management and prevention: GINA executive summary. Eur. Respir. J.31(1), 43–178, (2008)

- Expert Panel Report 3 (EPR-3). Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of asthma – summary report 2007. Allergy Clin. Immunol.120(5 Suppl.), S94–S138 (2007).

- Bacharier LB, Boner A, Carlsen KH et al. Diagnosis and treatment of asthma in childhood: a PRACTALL consensus report. Allergy63(5), 34 (2008).

- Rodrigo GJ. Rapid effects of inhaled corticosteroids in acute asthma: an evidence-based evaluation. Chest130, 1301–1311 (2006).

- Volovitz B. Inhaled budesonide in the management of acute worsenings and exacerbations of asthma: a review of the evidence. Respir. Med.101, 685–695 (2007).

- Volovitz B, Nussinovitch M. Management of children with severe asthma exacerbation in the emergency department. Paediatr. Drugs4, 141–148 (2002).

- Rachelefsky G. Treating exacerbations of asthma in children: the role of systemic corticosteroids. Pediatrics112, 382–397 (2003).

- Volovitz B, Bentur L, Finkelstein Y et al. Effectiveness and safety of inhaled corticosteroids in controlling acute asthma attacks in children who were treated in the emergency department: a controlled comparative study with oral prednisolone. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol.102, 605–609 (1998).

- Pedersen S. Clinical safety of inhaled corticosteroids for asthma in children: an update of long-term trials. Drug Saf.29, 599–612 (2006).

- Barnes PJ. Inhaled glucocorticoids for asthma. N. Engl. J. Med.332, 868–875 (1995).

- Volovitz B, Kauschansky A, Nussinovitch M, Harel L, Varsano I. Normal diurnal variation in serum cortisol concentration in asthmatic children treated with inhaled budesonide. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol.96, 874–878 (1995).

- Volovitz B, Amir J, Malik H, Kauschansky A, Varsano I. Growth and pituitary–adrenal function in children with severe asthma treated with inhaled budesonide. N. Engl. J. Med.329, 1703–1708 (1993).

- De Benedictis FM, Del Giudice MM, Vetrella M et al. Nebulized fluticasone propionate vs. budesonide as adjunctive treatment in children with asthma exacerbation. J. Asthma42, 331–336 (2005).

- Lin RY, Newman TG, Sauter D et al. Association between reported use of inhaled triamcinolone and differential short-term responses to aerosolized albuterol in asthmatics in an emergency department setting. Chest106, 452–457 (1994).

- Horvath G, Wanner A. Inhaled corticosteroids: effects on the airway vasculature in bronchial asthma. Eur. Respir. J.27, 172–187 (2006).

- Wanner A, Horvath G, Brieva JL, Kumar SD, Mendes ES. Nongenomic actions of glucocorticosteroids on the airway vasculature in asthma. Proc. Am. Thorac. Soc.1, 235–238 (2004).

- Urbach V, Walsh DE, Mainprice B, Bousquet J, Harvey BJ. Rapid non-genomic inhibition of ATP-induced Cl- secretion by dexamethasone in human bronchial epithelium. J. Physiol.545, 869–878 (2002).

- Kelly L, Kolbe J, Mitzner W, Spannhake EW, Bromberger-Barnea B, Menkes H. Bronchial blood flow affects recovery from constriction in dog lung periphery. J. Appl. Physiol.60, 1954–1959 (1986).

- Connett G, Lenney W. Prevention of viral induced asthma attacks using inhaled budesonide. Arch. Dis. Child.68, 85–87 (1993).

- Svedmyr J, Nyberg E, Asbrink-Nilsson E, Hedlin G. Intermittent treatment with inhaled steroids for deterioration of asthma due to upper respiratory tract infections. Acta Paediatr.84, 884–888 (1995).

- Wilson NM, Silverman M. Treatment of acute, episodic asthma in preschool children using intermittent high dose inhaled steroids at home. Arch. Dis. Child.65, 407–410 (1990).

- Volovitz B, Bilavsky E, Nussinovitch M. Effectiveness of high repeated doses of inhaled budesonide or fluticasone in controlling acute asthma exacerbations in young children. J. Asthma45(7), 561–567 (2008).

- Mannan SE, Yousef E, Mcgeady SJ. Early intervention with high-dose inhaled corticosteroids for control of acute asthma exacerbations and improved outcomes: a randomized controlled trial. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol.121(Suppl. 1), S219 (2008).

- Nuhoglu Y, Bahceciler NN, Barlan IB, Müjdat Basaran M. The effectiveness of high-dose inhaled budesonide therapy in the treatment of acute asthma exacerbations in children. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol.86, 318–322 (2001).

- Volovitz B, Nussinovitch M, Finkelstein Y, Harel L, Varsano I. Effectiveness of inhaled corticosteroids in controlling acute asthma exacerbations in children at home. Clin. Pediatr. (Phila.)40, 79–86 (2001).

- McKean M, Ducharme F. Inhaled steroids for episodic viral wheeze of childhood. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev.2, CD001107 (2000).

- Scarfone RJ, Loiselle JM, Wiley JF 2nd, Decker JM, Henretig FM, Joffe MD. Nebulized dexamethasone versus oral prednisone in the emergency treatment of asthmatic children. Ann. Emerg. Med.26, 480–486 (1995).

- Matthews EE, Curtis PD, McLain BI, Morris LS, Turbitt ML. Nebulized budesonide versus oral steroid in severe exacerbations of childhood asthma. Acta. Paediatr.88, 841–843 (1999).

- Devidayal Singhi S, Kumar L, Jayshree M. Efficacy of nebulized budesonide compared with oral prednisolone in acute bronchial asthma. Acta Paediatr.88, 835–840 (1999).

- Manjra AI, Price J, Lenney W, Hughes S, Barnacle H. Efficacy of nebulized fluticasone propionate compared with oral prednisolone in children with an acute exacerbation of asthma. Respir. Med.94, 1206–1214 (2000).

- Milani GK, Rosário Filho NA, Riedi CA, Figueiredo BC. Nebulized budesonide to treat acute asthma in children. J. Pediatr. (Rio J.)80, 106–112 (2004).

- Songhai S, Banerjee S, Nanjundaswamy H. Inhaled budesonide in acute asthma. J. Paediatr. Child Health35, 483–487 (1999).

- Sung L, Osmond MH, Klassen TP. Randomized, controlled trial of inhaled budesonide as an adjunct to oral prednisone in acute asthma. Acad. Emerg. Med.5, 209–213 (1998).

- Edmonds ML, Camargo CA Jr, Pollack CV Jr, Rowe BH. Early use of inhaled corticosteroids in the emergency department treatment of acute asthma. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev.3, CD002308 (2003).

- Schuh S, Reisman J, Alshehri M et al. A comparison of inhaled fluticasone and oral prednisone for children with severe acute asthma. N. Engl. J. Med.343, 689–694 (2000).

- Schuh S, Dick PT, Stephens D et al. High-dose inhaled fluticasone does not replace oral prednisolone in children with mild to moderate acute asthma. Pediatrics118, 644–650 (2006).

- Daugbjerg P, Brenoe E, Forchhammer H et al. A comparison between nebulized terbutaline, nebulized corticosteroid and systemic corticosteroid for acute wheezing in children up to 18 months of age. Acta Paediatr.82, 547–551 (1993).

- Sano F, Cortez GK, Sole D, Naspitz CK. Inhaled budesonide for the treatment of acute wheezing and dyspnea in children up to 24 months old receiving intravenous hydrocortisone. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol.105(4), 699–703 (2000).

- Volovitz B, Soferman R, Blau H, Nussinovitch M, Varsano I. Rapid induction of clinical response with a short-term high-dose starting schedule of budesonide nebulizing suspension in young children with recurrent wheezing episodes. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol.101, 464–469 (1998).

- Garrett J, Williams S, Wong C, Holdaway D. Treatment of acute asthmatic exacerbations with an increased dose of inhaled steroid. Arch. Dis. Child.79, 12–17 (1998).

- Harrison TW, Oborne J, Newton S, Tattersfield AE. Doubling the dose of inhaled corticosteroid to prevent asthma exacerbations: randomised controlled trial. Lancet363, 271–275 (2004).

- FitzGerald JM, Becker A, Sears MR, Mink S, Chung K, Lee J. Doubling the dose of budesonide versus maintenance treatment in asthma exacerbations. Thorax59, 550–556 (2004).

- Principi N, Esposito S. Emerging role of Mycoplasma pneumoniaeand Chlamydia pneumoniae in paediatric respiratory-tract infections. Lancet Infect. Dis.1, 334–344 (2001).

- Amsden GW. Anti-inflammatory effects of macrolides – an underappreciated benefit in the treatment of community-acquired respiratory tract infections and chronic inflammatory pulmonary conditions? J. Antimicrob. Chemother.55, 10–21 (2005).

- D’Urzo AD. Inhaled glucocorticosteroid and long-acting β2-adrenoceptor agonist single-inhaler combination for both maintenance and rescue therapy: a paradigm shift in asthma management. Treat. Respir. Med.5, 385–391 (2006).

- Bisgaard H, Le Roux P, Bjamer D, Dymek A, Vermeulen JH, Hultquist C. Budesonide/formoterol maintenance plus reliever therapy: a new strategy in pediatric asthma. Chest130, 1733–1743 (2006).

Websites

- Global Initiative for Asthma: global strategy for asthma management and prevention (2007) www.ginasthma.org/guidelineitem.asp??l1=2&l2=1&intId=60

- The Global Initiative for Asthma: pocket guide for asthma management and prevention (2006) www.ginasthma.org/guidelineitem.asp??l1=2&l2=1&intId=37

- To learn more about asthma… www.volovitz.co.il