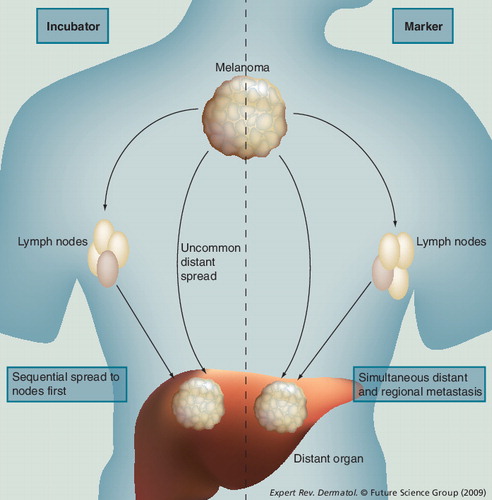

The incubator hypothesis: primary melanoma spreads first to regional draining nodes and only subsequently to distant sites. The marker hypothesis: spread occurs simultaneously to nodal and distant sites.

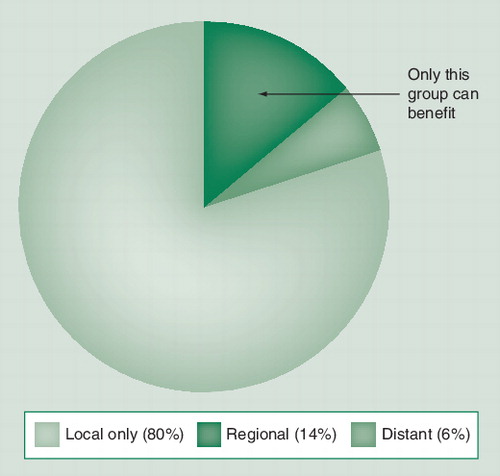

The majority of cases (80%) are limited to the primary site, while a smaller fraction (6%) have disease already beyond the regional nodes. Only those with nodal disease but not systemic disease (14%) will be cured by early nodal excision.

Subgroup 1: patients with positive sentinel lymph node (SLN). Subgroup 2: those with positive SLN or false-negative SLN. Subgroup 3: those with nodal recurrence in the wide excision-alone arm.

Subgroup 4: those with false-negative SLN.

Redrawn with permission from Citation[7] © 2006 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

![Figure 3. Melanoma-specific survival in the Multicenter Selective Lymphadenectomy Trial clinical trial.Subgroup 1: patients with positive sentinel lymph node (SLN). Subgroup 2: those with positive SLN or false-negative SLN. Subgroup 3: those with nodal recurrence in the wide excision-alone arm.Subgroup 4: those with false-negative SLN.Redrawn with permission from Citation[7] © 2006 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.](/cms/asset/463f8e8e-77bb-43fe-898a-c486ea2f0c95/ierg_a_11208297_f0003_b.jpg)

The controversy surrounding the treatment of lymph nodes in clinically localized melanoma has swirled for over 100 years since Herbert Snow initiated the controversy at the end of the 19th Century. A cancer surgeon at the London Cancer Hospital (a forerunner to the current Royal Marsden Hospital), Snow advocated early removal, saying:

“It is essential to remove, whenever possible, those lymph glands which first receive the infective protoplasm, and bar its entrance into the blood, before they have undergone increase in bulk. This is ‘Anticipatory Gland-Excision’, a simple common-sense measure, adding nothing to the gravity of a surgical operation, while most materially enhancing its efficacy. A radical cure is alone thus rendered possible in the more common instance of the more common forms of ‘Cancer’. It was, and unfortunately, too often still is, the custom to neglect the infected glands unless palpably enlarged”Citation[1].

The rationale for early treatment of regional nodes was based on the observation that melanoma usually progresses in a predictable fashion from the primary site to regional lymph nodes and is only detected subsequently in distant sites. Two competing hypotheses describe progression of malignant cells from the primary site to both regional lymph nodes and distant sites. These are the ‘incubator hypothesis’, in which metastatic disease is limited to regional nodes for a period prior to spreading further, and the ‘marker hypothesis’, in which nodal disease is merely an indicator of a metastatic phenotype . Under the incubator hypothesis, early removal of nodal metastases will improve survival. Under the marker hypothesis, early removal provides only prognostic information and has no therapeutic value.

Most of the components of Snow’s aforementioned assertion have been challenged in the intervening century. Numerous retrospective studies confirmed the prognostic significance of nodal metastases and suggested that those patients diagnosed and treated for the metastatic disease prior to clinical detection enjoyed a much better outcome than those who were treated only after the metastases became clinically apparent. Elective lymph node dissection became practiced by a number of surgical oncologists based on these data, but the procedure was not universally accepted. Eventually, a series of randomized clinical trials were performed in which patients with clinically localized melanoma received either elective complete lymph node dissection initially or therapeutic lymph node dissection upon clinical recurrence in the nodal basin.

Two of these trials enrolled patients with all thicknesses of melanoma and neither showed a significant advantage for early nodal treatment Citation[2,3]. Two other trials specifically examined patients with intermediate-thickness melanoma for entry into the trial or a planned subgroup analysis. In the WHO trial number 14, there was a significant survival advantage seen among patients with melanoma between 1.5 and 4 mm in thickness (p = 0.03) Citation[4]. In the Intergroup Melanoma Trial, significant benefits were seen for patients with nonulcerated melanoma (p = 0.03), extremity melanoma (p = 0.05) and lesions 1–2 mm in thickness (p = 0.03) Citation[5]. However, the overall group in this trial showed only a trend toward improved survival (p = 0.12) Citation[5]. These trials, therefore, did not end the controversy regarding treatment of lymph nodes in melanoma.

However, there is a basic difficulty with all of these trials. Since only a minority (∼20%) of patients with intermediate-thickness melanoma will ever develop nodal metastasis, the bulk of patients in the trials have normal lymph nodes and cannot possibly derive any benefit from their removal. Of those with nodal disease, approximately 30% will have concomitant distant metastases and cannot benefit either . Since there is no way to select these patients preoperatively, all patients with intermediate-thickness melanoma must be included and suffer the morbidity of a complete lymph node dissection, even though for most it is not helpful. This is similar to conducting a trial of a targeted cancer drug, such as trastuzumab, without selecting for patients whose tumors expressed the receptor. Any such trial would naturally be statistically negative given the dilution of a therapeutic effect by large numbers of patients who could not benefit. This difficulty became apparent to Donald Morton, who examined the question of determining whether patients with clinically occult nodal metastasis could be identified prior to complete lymph node dissection Citation[6]. He subsequently developed the sentinel lymph node (SLN) biopsy technique, which allowed for identification of these patients Citation[6].

After validation of the technique’s accuracy in single-institution studies, the first Multicenter Selective Lymphadenectomy Trial (MSLT) was initiated Citation[7]. The trial was conducted at melanoma centers in the USA, Europe and Australia, and randomized 2001 patients to undergo wide local excision (WLE) of their primary melanoma alone or with lymphatic mapping and sentinel lymphadenectomy. Complete lymph node dissections were performed if the SLN had metastasis or after a clinical nodal recurrence. The primary analysis stratum included patients with primary melanoma 1.2–3.5 mm in thickness.

The results of the trial were published after several of the secondary end points showed clinical and statistical significance, even though the final analysis of the primary end point, melanoma-specific survival, was still pending and did not show a significant difference Citation[7]. The significant secondary end points included improved disease-free survival, a significant prognostic impact of SLN status (the most powerful factor) and improved melanoma-specific survival among patients with metastasis detected by SLN biopsy or by clinical recurrence. These data confirmed the role of SLN biopsy for patients with intermediate-thickness melanoma, but disagreement remains over the impact of early nodal treatment on overall survival. Since the MSLT trial could never ethically be run again, given the importance of SLN information to melanoma patients, we must try to draw conclusions based upon the data we have available, pending the remaining interim and final analyses of MSLT. The preponderance of evidence strongly suggests that a survival benefit is imparted by early removal of nodal metastases.

Essentially, the MSLT trial was hampered in detecting an overall survival benefit in the same way the prior elective lymph node dissection trials were hampered: the majority of patients had normal lymph nodes at the time of trial entry and could not benefit. Only those patients with nodal metastases could possibly benefit from their removal and the comparison of survival of patients with nodal disease is most telling of the impact of early treatment on the course of disease progression. Comparison of melanoma-specific survival between patients with SLN metastasis and those with clinical recurrence in the WLE-alone arm demonstrates a dramatic decrease in melanoma deaths in the group whose disease was removed early . The relative risk for this comparison (subgroup 1 vs 3) is 0.51, suggesting that the risk of melanoma death is reduced by almost 50% following early removal of metastases. Since there are false-negative SLN biopsies, the actual impact on survival for those with nodal metastases is diminished. However, even taking this into account (subgroup 2 vs 3), a relative risk of 0.63 still favors the SLN group and, at institutions with lower false-negative rates than those seen in this multicenter study, the benefit is probably closer to the former value.

There has been objection to using this comparison, based on the fact that these patients were not randomized into the two groups that are being compared. It is argued that the two groups may not be biologically equivalent and that many of the metastases found in SLN are not clinically relevant but are, in fact, false positives. However, the data support the assertion that the two groups are biologically equivalent and that essentially all of these metastases are clinically relevant. Furthermore, the comparison, although not as statistically pure as one would wish for, is necessary if we are to determine the impact of early nodal treatment in patients with clinically occult nodal metastases.

Regarding the issue of the biological comparability of the two groups with nodal disease, we can examine their other prognostic characteristics to determine if there is any imbalance that might explain the marked difference in outcome; there is not. When compared by Breslow thickness (2.19 vs 2.32 mm in the positive SLN and clinical nodal recurrence groups, respectively), gender (60.7 vs 60.3% male), ulceration (30.3 vs 30.8%) and primary tumor site, the group with positive sentinel nodes was virtually identical to that with clinical nodal recurrence. Only in age was there a statistical difference, with the sentinel node arm being slightly younger (50 vs 54 years). These findings do not suggest the likelihood of more aggressive disease in the group that was assigned to WLE alone.

It has been argued that, since the rate of nodal disease in the sentinel lymphadenectomy arm is currently higher than that of the WLE arm, a number of the metastases found in SLN were not clinically significant and were, therefore, false-positives. This reasoning is mistaken due to the effect of the length of follow-up on the perceived rate of nodal metastasis in each arm. The SLN arm started with 16% positive sentinel nodes. At that time, there were no positive nodes in the WLE arm so, by this argument, the rate of false-positives was 16% at that point. However, as time passes, recurrences begin to accumulate in the WLE arm as they do to a lesser degree in the SLN arm. By a more appropriate actuarial analysis, the rates of nodal disease will become equal between 8 and 10 years of follow-up, at approximately 20% in both groups. So it appears that all of the detected SLN metastases are clinically relevant, although the low burden of disease means that it takes time for them to present.

Finally, the use of this comparison of patients with nodal disease is absolutely necessary given the realities of current melanoma treatment. SLN biopsy provides unambiguous benefits in terms of recurrence-free survival and prognostic assessment. These benefits are of sufficient value to preclude the possibility of ever randomizing patients with intermediate-thickness melanoma to WLE alone again. MSLT I cannot be repeated. Owing to the low event rate overall in MSLT, the trial may not be powered sufficiently to detect a real survival benefit, even if the risk of melanoma death is halved by early removal of occult nodal metastasis, as appears to be the case. Therefore, we must interpret the data that are available as reasonably and intelligently as possible, rather than cling to dogma. Our patients deserve this consideration.

Acknowledgements

The Multicenter Selective Lymphadenctomy Trials mentioned in this editorial are supported by funding from the National Cancer Institute (CA29605).

Financial & competing interests disclosure

The author has no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

References

- Neuhaus SJ, Clark MA, Thomas JM. Dr. Herbert Lumley Snow, MD, MRCS (1847–1930): the original champion of elective lymph node dissection in melanoma. Ann. Surg. Oncol.11(9), 875–878 (2004).

- Veronesi U, Adamus J, Bandiera DC et al. Delayed regional lymph node dissection in stage I melanoma of the skin of the lower extremities. Cancer49(11), 2420–2430 (1982).

- Sim FH, Taylor WF, Ivins JC et al. A prospective randomized study of the efficacy of routine elective lymphadenectomy in management of malignant melanoma. Preliminary results. Cancer41(3), 948–956 (1978).

- Cascinelli N, Morabito A, Santinami M et al. Immediate or delayed dissection of regional nodes in patients with melanoma of the trunk: a randomised trial. WHO Melanoma Programme. Lancet351(9105), 793–796 (1998).

- Balch CM, Soong S, Ross MI et al. Long-term results of a multi-institutional randomized trial comparing prognostic factors and surgical results for intermediate thickness melanomas (1.0 to 4.0 mm). Intergroup Melanoma Surgical Trial. Ann. Surg. Oncol.7(2), 87–97 (2000).

- Morton DL, Wen DR, Wong JH et al. Technical details of intraoperative lymphatic mapping for early stage melanoma. Arch. Surg.127(4), 392–399 (1992).

- Morton DL, Thompson JF, Cochran AJ et al. Sentinel-node biopsy or nodal observation in melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med.355(13), 1307–1317 (2006).