Abstract

Obesity/higher BMI appears to be important determinants in the development of colon cancer as well as in predicting outcomes in the adjuvant setting in these patients. These associations seem to be stronger for men and tend to be ‘J-shaped’, with worse outcomes in both lower and upper BMI categories than in the middle categories. How this factors in the metastatic setting is less clear. A recent pooled analysis of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer receiving bevacizumab in the first-line setting observed that patients with the lowest BMI had the lowest median overall survival. An incremental BMI increase of 5 kg/m2 led to actually a decrease in the risk of death (hazard ratio, 0.911 [95% CI, 0.879–0.944]). The observed association does not necessarily mean that obesity is an advantage for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. More likely, it is conceivable that, in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer with a lower BMI, the effects of cancer-related cachexia may be more deleterious than the potential adverse events related to a higher BMI. In patients already diagnosed with metastatic disease, studying how body weight affects tumor biology and treatment-related decisions are important considerations.

Obesity is an established risk factor for development of colon cancer. A recent pooled analysis showed that with each 5 kg increase in adult weight gain, there was an estimated 6% increased risk of colon cancer incidence (risk ratio [RR] = 1.06, 95% CI = 1.03) Citation[1,2]. Similar results were reported by Larsson et al. with a 5-unit increase in BMI leading to an increased risk of carcinogenesis Citation[2]. These associations seem to be stronger for men Citation[1–3]. The ‘Health Professionals Follow-Up Study’ that included 46,349 men over a prospective 28-year period, the ‘Melbourne Collaborative Cohort Study’ with 16,188 men and 23,438 women with almost a 14-year follow-up, and the ‘Norwegian population-based Study’ of 8,822 men and 37,357 women corroborated these findings Citation[4–6].

In evaluating outcomes after diagnosis in the adjuvant setting, Dignam et al. reported worse outcomes (recurrent colon cancer, second primary tumor and/or mortality) for patients with a very high BMI (≥35 kg/m2) compared with normal weight patients (18.5–24 kg/m2) Citation[7]. Underweight patients (BMI <18.5 kg/m2) also were at risk for higher mortality. However, the deaths reported in the latter group of patients were more non-cancer related compared with the very high BMI group, in which deaths were attributed to colon cancer Citation[7]. Similarly, analysis of the Adjuvant Colon Cancer Endpoints database utilizing more than 20,000 patients with colon cancer receiving chemotherapy in the adjuvant setting showed inferior outcomes both for obese as well as underweight individuals Citation[8]. The worse outcomes for both obese and underweight individuals in the Adjuvant Colon Cancer Endpoints database appeared to be cancer-related Citation[8]. Associations with a variable such as BMI tend to be ‘J-shaped’, with worse outcomes in both ‘lower and upper BMI categories than in the middle categories’ Citation[9].

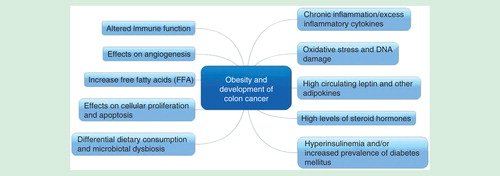

From the data reported thus far, obesity and higher BMI appear be to important factors in cancer development as well as predictors of outcomes in the adjuvant setting in these patients. Pathophysiology implicated in patients with obesity is outlined in Citation[10]. It is likely that signaling pathways involved in obesity-related colon cancers are different as well Citation[10–12]. How this factors in the metastatic setting is less clear. In general, the thought process is that patients who are obese tend to fare poorly due to several factors including: receipt of inadequate anti-cancer therapy; presence of other comorbidities; and higher postoperative adverse events and longer hospital stay after colorectal surgery Citation[13,14]. With respect to diabetes, for example, colon cancer patients were noted have higher rates of recurrence and mortality Citation[15]. It is not entirely clear if it is only the all-cause mortality versus any direct contribution of diabetes to cancer-specific mortality as well Citation[16]. In a meta-analysis, diabetes appeared to increase the risk of developing colon cancer by 30%, even when controlled for BMI for some of the studies that included this variable in their analysis Citation[17]. Pathophysiology behind these postulated mechanisms is being extensively studies and the outcomes are likely a complex interplay of all these factors .

In a pooled analysis of 6128 patients from four large, prospective, US and European registry studies of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer receiving bevacizumab in the first-line setting, patients with the lowest BMI experienced the lowest median overall survival Citation[18]. A BMI increase of 5 kg/m2 led to a decrease in the risk of death (hazard ratio, 0.911 [95% CI, 0.879–0.944]). In this particular study presented at the World Congress on Gastrointestinal Cancer 2015, the patients were divided into four categories based on their BMI: <25, 25–29, 30–35 and ≥35 kg/m2 respectively. This relationship persisted after adjusting for study, age, ECOG performance status, gender, and hypertension in the four groups of patients Citation[18].

The observed association does not necessarily mean that obesity is an advantage in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. More likely, it is postulated that in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer with a lower BMI, the effects of cancer-related cachexia may be more deleterious than the potential adverse events related to a higher BMI. Being underweight may also be a surrogate marker of the advanced or aggressive nature of disease paired with lesser treatment tolerated by those patients with a lower BMI. Tumor, environmental and patient-related biologic factors might also explain the relationship between BMI and outcome. For example, it is noted in studies that smokers tend to have a lower BMI and overall worse outcomes Citation[19]. Additionally, obesity and the associated metabolic dysfunction may promote angiogenesis, and one can speculate that maybe anti-angiogenic targeting VEGF-based treatments may have a more of role to play in obese patients. This might explain slightly better outcomes in obese patients receiving bevacizumab in our cohort of patients evaluated. However, other studies have shown contradictory results, postulating decreased efficacy of bevacizumab in obese patients Citation[13,20,21]. In fact, response rates, time to progression as well as survival was worse in patients receiving bevacizumab with a higher BMI Citation[21]. The authors speculate it might be higher circulating levels of VEGF conferring resistance to bevacizumab alongside higher volume of distribution in obese patients Citation[13]. Furthermore, in another study, obese patients with colon cancer were less likely to have deficient mismatch repair status (10 vs 17%, p-value <0.001), which maybe another factor affecting outcome in these patients Citation[22].

Whether patients with metastatic colorectal cancer with a lower BMI need a more aggressive or altered treatment approach is open to debate. The question could be better informed by trials that prospectively assess BMI for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Utilizing animal models for studying obesity-related colon cancer can further help elucidate some of these mechanisms Citation[23].

How obesity factors in with other modifiable factors such as physical activity and diet in terms of increasing or decreasing the risk of colon cancer, respectively, are important observations Citation[24–26]. However, it is not just the BMI or obesity or being underweight that are solely responsible; but likely more so the dynamic changes in weight with time in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer that are likely to be playing a role and reflective of other comorbidities and nutritional status in this patient population. How these environmental exposures can affect the development of malignancies and how early these changes can be important is an area of increasing interest Citation[27].

Additionally, we must be cautious in interpreting these results since BMI might be only a part of the clinical picture when considering body weight and cancer Citation[28,29]. For example, patients with low BMI might still be viscerally obese. In an interesting observation by Cakir et al., visceral obesity was noted to be a predictor of worse outcome after surgery in patients with resectable colon cancer Citation[30]. However, outcomes were worse among patients with BMI <25 kg/m2, although up to 44% in this group also had visceral obesity Citation[30]. In another study, while only 3.2% of the patients met the criteria for obesity (BMI >30 kg/m2), more than two-thirds of the patients met the criteria for visceral obesity Citation[31]. So it is not only the ‘general obesity’ but also the ‘abdominal obesity’ that can be assessed with clinical measurements like waist-to-hip ratio or waist circumference that may be determining outcomes in these patients Citation[9]. Incorporating surrogate radiological measures is also an accurate and cost-effective method, as patients with colon cancer might receive several CT scans during the course of their disease Citation[30,32]. Furthermore, it is important to note that a proportion of overweight/obese patients may still be ‘metabolically healthy’ (normal glucose tolerance, lipid levels, and blood pressure as well as less ectopic fat) compared with those with ‘metabolic dysfunction,’ with overall higher risk and poorer outcomes in the latter group Citation[26].

With the rising prevalence of overweight and obese individuals, focusing on modifiable factors such as obesity is important and can have a significant impact in decreasing the burden of obesity-related malignancies such as colon cancer Citation[28]. In patients already diagnosed with metastatic disease, studying how body weight affects carcinogenesis, tumor biology, and ultimately, treatment-related decisions are important considerations.

Methodology

The selection of articles presented in this review was based on expert opinion with focus on landmark studies that have had practice-changing implications for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer, in the opinion of the authors. Data that were presented in the form of abstracts from recent meetings was also considered.

Financial & competing interests disclosure

A Grothey has received research support from Genentech, Bayer, Eisai, Pfizer and Eli-Lilly. Y. Zafar’s spouse has been employed by Novartis and has stocks in Novartis and GlaxoSmithKline. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

References

- Keum N, Greenwood DC, Lee DH, et al. Adult weight gain and adiposity-related cancers: a dose-response meta-analysis of prospective observational studies. J Natl Cancer Inst 2015;107:2

- Larsson SC, Wolk A. Obesity and colon and rectal cancer risk: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Am J Clin Nutr 2007;86(3):556-65

- Li H, Yang G, Xiang YB, et al. Body weight, fat distribution and colorectal cancer risk: a report from cohort studies of 134 255 Chinese men and women. Int J Obes 2013;37(6):783-9

- Thygesen LC, Thygesen LC, Grønbaek M, et al. Prospective weight change and colon cancer risk in male US health professionals. Inter J cancer 2008;123(5):1160-5

- Rodriguez C, Freedland SJ, Deka A, et al. Body mass index, weight change, and risk of prostate cancer in the Cancer Prevention Study II Nutrition Cohort. Am Soc Preven Oncol 2007;16(1):63-9

- Laake I, Thune I, Selmer R, et al. A prospective study of body mass index, weight change, and risk of cancer in the proximal and distal colon. Am Soc Preven Oncol 2010;19(6):1511-22

- Dignam JJ, Polite BN, Yothers G, et al. Body mass index and outcomes in patients who receive adjuvant chemotherapy for colon cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 2006;98(22):1647-54

- Sinicrope FA, Foster NR, Yothers G, et al. Body mass index at diagnosis and survival among colon cancer patients enrolled in clinical trials of adjuvant chemotherapy. Cancer 2013;119(8):1528-36

- Pischon T, Boeing H, Hoffmann K, et al. General and abdominal adiposity and risk of death in Europe. N Engl J Med 2008;359(20):2105-20

- Yehuda-Shnaidman E, Schwartz B. Mechanisms linking obesity, inflammation and altered metabolism to colon carcinogenesis. J Inter Assoc Study Obe 2012;13(12):1083-95

- Fazolini NP, Cruz AL, Werneck MB, et al. Leptin activation of mTOR pathway in intestinal epithelial cell triggers lipid droplet formation, cytokine production and increased cell proliferation. Cell cycle 2015:0

- Morikawa T, Kuchiba A, Liao X, et al. Tumor TP53 expression status, body mass index and prognosis in colorectal cancer. Inter J Cancer 2012;131(5):1169-78

- Simkens LH, Koopman M, Mol L, et al. Influence of body mass index on outcome in advanced colorectal cancer patients receiving chemotherapy with or without targeted therapy. Eur J Cancer 2011;47(17):2560-7

- Griggs JJ, Mangu PB, Anderson H, et al. Appropriate chemotherapy dosing for obese adult patients with cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline. J Clin Oncol 2012;30(13):1553-61

- Meyerhardt JA, Catalano PJ, Haller DG, et al. Impact of diabetes mellitus on outcomes in patients with colon cancer. J Clin Oncol 2003;21(3):433-40

- Stein KB, Snyder CF, Barone BB, et al. Colorectal cancer outcomes, recurrence, and complications in persons with and without diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Dig Dis Sci 2010;55(7):1839-51

- Larsson SC, Orsini N, Wolk A. Diabetes mellitus and risk of colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst 2005;97(22):1679-87

- Zafar Y, Hubbard J, Van Cutsem E, et al. Survival outcomes according to body mass index (BMI): results from a pooled analysis of 5 observational or phase IV studies of bevacizumab in metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC). ESMO World Congress on Gastrointestinal Cancer. Barcelona, 2015

- Adams KF, Schatzkin A, Harris TB, et al. Overweight, obesity, and mortality in a large prospective cohort of persons 50 to 71 years old. New Eng J Med 2006;355(8):763-78

- Bardou M, Barkun AN, Martel M. Republished: obesity and colorectal cancer. Postgrad Med J 2013;89(1055):519-33

- Guiu B, Petit JM, Bonnetain F, et al. Visceral fat area is an independent predictive biomarker of outcome after first-line bevacizumab-based treatment in metastatic colorectal cancer. Gut 2010;59(3):341-7

- Sinicrope FA, Foster NR, Yoon HH, et al. Association of obesity with DNA mismatch repair status and clinical outcome in patients with stage II or III colon carcinoma participating in NCCTG and NSABP adjuvant chemotherapy trials. J Clin Oncol 2012;30(4):406-12

- Chen J, Huang XF. High fat diet-induced obesity increases the formation of colon polyps induced by azoxymethane in mice. Ann Trans Med 2015;3(6):79

- Larsson SC, Rutegård J, Bergkvist L, et al. Physical activity, obesity, and risk of colon and rectal cancer in a cohort of Swedish men. Eur J Cancer 2006;42(15):2590-7

- Martinez ME, Giovannucci E, Spiegelman D, et al. Leisure-time physical activity, body size, and colon cancer in women. Nurses’ Health Study Research Group. J Natl Cancer Inst 1997;89(13):948-55

- Moore LL, Chadid S, Singer MR, et al. Metabolic health reduces risk of obesity-related cancer in Framingham study adults. Am Soc Preven Oncol 2014;23(10):2057-65

- Kantor ED, Udumyan R, Signorello LB, et al. Adolescent body mass index and erythrocyte sedimentation rate in relation to colorectal cancer risk. Gut 2015

- Stevens GA, Singh GM, Lu Y, et al. National, regional, and global trends in adult overweight and obesity prevalences. Popul Health Metr 2012;10(1):22

- Arnold M, Pandeya N, Byrnes G, et al. Global burden of cancer attributable to high body-mass index in 2012: a population-based study. Lancet Oncol 2015;16(1):36-46

- Cakir H, Heus C, Verduin WM, et al. Visceral obesity, body mass index and risk of complications after colon cancer resection: A retrospective cohort study. Surgery 2015;157(5):909-15

- Park SW, Lee HL, Doo EY, et al. Visceral Obesity Predicts Fewer Lymph Node Metastases and Better Overall Survival in Colon Cancer. J Gastroint Sur 2015;19(8):1513-21

- Yoshizumi T, Nakamura T, Yamane M, et al. Abdominal fat: standardized technique for measurement at CT. Radiology 1999;211(1):283-6