Abstract

Onychomycosis in children is rare, with an approximate worldwide prevalence in children below the age of 18 years of lower than 0.5%. Dermatophytes are responsible for the majority of the cases, with distal subungual onychomycosis of one toenail the most frequent clinical variety. Candida sp. may invade the nails only in predisposed children, usually producing a total onychomycosis. Care should be taken when diagnosing onychomycosis in children, as the sole clinical appearance is not enough to establish a diagnosis and mycology is always mandatory.

Medscape: Continuing Medical Education Online

This activity has been planned and implemented in accordance with the Essential Areas and policies of the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education through the joint sponsorship of Medscape, LLC and Expert Reviews Ltd. Medscape, LLC is accredited by the ACCME to provide continuing medical education for physicians.

Medscape, LLC designates this Journal-based CME activity for a maximum of 1 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit(s)™. Physicians should claim only the credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity.

All other clinicians completing this activity will be issued a certificate of participation. To participate in this journal CME activity: (1) review the learning objectives and author disclosures; (2) study the education content; (3) take the post-test with a 70% minimum passing score and complete the evaluation at www.medscape.org/journal/expertderm; (4) view/print certificate.

Release date: 11 December 2012; Expiration date: 11 December 2013

Learning objectives

Upon completion of this activity, participants should be able to:

• Assess the epidemiology and etiology of onychomycosis among children

• Distinguish the clinical presentation of onychomycosis among children

• Analyze the differential diagnosis of nail disorders among children

• Evaluate the management of onychomycosis among children

Financial & competing interests disclosure

EDITOR

Elisa Manzotti

Publisher, Future Science Group, London, UK

Disclosure: Elisa Manzotti has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

CME AUTHOR

Charles P Vega, MD

Health Sciences Clinical Professor; Residency Director, Department of Family Medicine, University of California, Irvine, CA, USA.

Disclosure: Charles P Vega, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

AUTHORS AND CREDENTIALS

Bianca Maria Piraccini, MD

Department of Specialised Experimental and Diagnostic Medicine, University of Bologna, Bologna, Italy

Disclosure: Bianca Maria Piraccini, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Michela Starace, MD

Department of Specialised Experimental and Diagnostic Medicine, University of Bologna, Bologna, Italy

Disclosure: Michela Starace, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Francesca Bruni, MD

Department of Specialised Experimental and Diagnostic Medicine, University of Bologna, Bologna, Italy

Department of Specialised Experimental and Diagnostic Medicine, University of Bologna, Bologna, Italy

Mild erythema and scaling.

Differential diagnosis with distal subungual onychomycosis requires mycology.

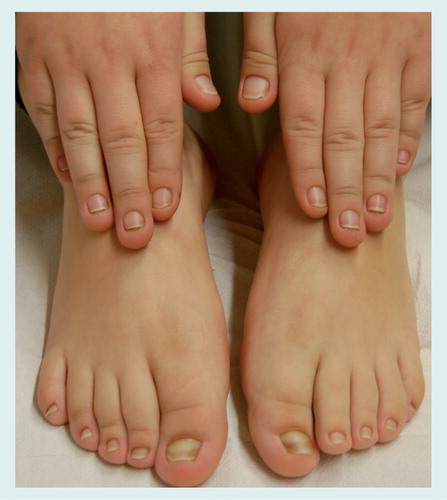

Nail lesions in a 7-year-old boy. All nails show mild thickening with distal onycholysis and subungual hyperkeratosis.

Diffuse crumbling of the nail plate.

Onycholysis with erythematous border and splinter hemorrhages.

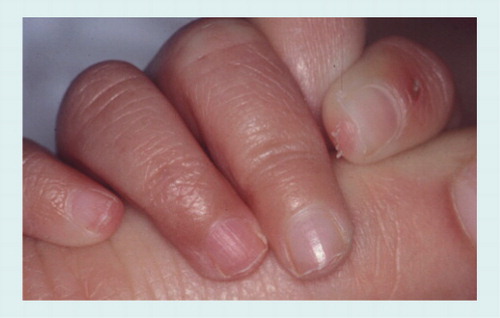

A single fingernail showing mild subungual hyperkeratosis and onycholysis, associated with periungual scaling. Note traumatic punctate leukonychia of the fifth fingernail.

Isolation of Candida indicates secondary colonization and not primary invasion.

Onychomycosis is traditionally a disease of the elderly, with prevalence increasing above the age of 60 years Citation[1]. However, this diagnosis cannot be excluded in children presenting with suggestive nail abnormalities, and mycology should be performed. After a review in 2009 Citation[2], other articles have been published reporting onychomycosis in children, sometimes as single case reports Citation[3–5], other times as case series Citation[6–11].

This review will cover old and new data on onychomycosis in children with regards to prevalence, etiological agents, predisposing factors, clinical features and treatment. A special section has been devoted to differential diagnosis of onychomycosis in children, a task that sometimes is not adequately considered.

Prevalence of onychomycosis in children: is there any change?

Onychomycosis in children is rare. The prevalence that results from new articles, even if difficult to assess, confirms a worldwide prevalence of onychomycosis in children below the age of 18 years of lower than 0.5%, with higher numbers in some countries. A case series study from Peru reports, in fact, a prevalence of onychomycosis in adolescents aged 12–17 years of 3.4% Citation[8], figures similar to those found years ago in other tropical countries such as Mexico and Guatemala Citation[12,13]. This higher prevalence of onychomycosis in children in countries with a hot climate is not related to causative fungi, that is dermatophytes and Trichophyton rubrum in particular, the responsible pathogens in all series, but it is possibly related to the humid feet environment that facilitates tinea pedis. Although the prevalence of onychomycosis increases with child age, with higher frequency above the age of 12 years, cases in infants can indeed occur.

Etiological agents: dermatophytes

Dermatophytes are responsible for the great majority of onychomycosis in children, accounting for more than 95% of cases. Nondermatophyte molds are extremely rare. Among dermatophytes, the prevalence of the different species parallels that of adults, with T. rubrum and Trichophyton interdigitale as the most common causes.

A study on onychomycosis observed in children in a 20-year period in the sanitary area of Santiago de Compostela, Spain, has reported several cases of onychomycosis of the fingernails and toenails due to Trichophyton tonsurans, not associated with tinea capitis Citation[10]. The authors related this emerging pathogen as a sign of migratory phenomenon and suggest to look for tinea capitis in children with T. tonsurans fingernail onychomycosis. In the same way, Microsporum canis can invade the nails in children with tinea capitis due to this dermatophyte, but this occurrence is very rare, probably due to the low capacity of Microsporum canis for invading hard keratins.

Candida sp. may invade the nails – both fingernails and toenails, in predisposed children – as occurs in premature newborns and in children with iatrogenic or genetic immunodeficiencies.

Predisposing factors: tinea pedis, family history & immunodepression

The most important predisposing factors for dermatophyte onychomycosis in children include tinea pedis and family members affected by onychomycosis or tinea pedis. It is well-known that anthropophylic dermatophytes such as T. rubrum and T. interdigitale may produce chronic foot disease in several members of the same family due to a genetic predisposition to the infection Citation[14]. Tinea pedis in children is usually moccasin-type and very mild. It clinically presents with bilateral slight erythema of the sole with mild scaling .

The use of occlusive shoes, feet trauma and barefoot contact with the soil are, on the other hand, still not proven predisposing factors for the development of onychomycosis in children. Predisposing factors to Candida onychomycosis are all types of immunodeficiencies, including incomplete development of the immune system in premature newborns, chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis and iatrogenic immunodeficiencies.

Clinical features: do not overestimate!

Distal and lateral subungual onychomycosis is the most common clinical presentation of onychomycosis owing to dermatophytes in children, as it is in adults Citation[15]. The affected nail, usually a single toenail in children, presents a disto-lateral area of onycholysis and a mild-to-moderate subungual hyperkeratosis . The color of the detached area ranges from white to yellow to orange.

Superficial onychomycosis, both in its ‘deep’ and ‘classic’ varieties, is rare and especially found in young children. In the ‘classic’ variety of superficial onychomycosis, the nail plate of one or several toenails shows multiple small, whitish opaque friable patches that are easily scraped away . The ‘deep’ variety of superficial onychomycosis presents with a larger and deeper nail plate involvement . Proximal subungual onychomycosis in children is uncommon, while total onychomycosis can occur as an evolution of any form, when fungi grow to colonize the whole nail.

Onychomycosis owing to Candida may present as disto-lateral subungual onychomycosis, usually affecting fingernails and toenails , and as superficial onychomycosis. Paronychia is frequently associated with any form of Candida onychomycosis and is especially severe in children affected with chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis.

Differential diagnosis of onychomycosis in children

Care should be taken when diagnosing onychomycosis in children, as the sole clinical appearance is not enough to establish the diagnosis and mycology is always mandatory. Potassium hydroxide (KOH) and cultures are still the easiest way to confirm the clinical diagnosis of onychomycosis, as other techniques, including PAS stain of nail clippings and PCR, are not always available. Differential diagnosis may sometimes be difficult, especially in older children who may have nail diseases that are, on the other hand, rare before the age of 5 years Citation[16]. Dermatophyte onychomycosis is frequently restricted to one digit, usually the toenail, but a fingernail can also be affected. Candida onychomycosis frequently occurs in all digits and is most severe in the fingernails.

Diseases that should be excluded in differential diagnosis with onychomycosis in children are listed in Box 1.

Congenital malalignment of the great toenail

The condition is not rare but is frequently undiagnosed. The nail plate of one of both the big toenails deviates laterally from the longitudinal axis of the distal phalanx. Congenital malalignment is already present at birth, but the nail becomes thickened and discolored with aging, clinical dystrophy being evident at around the age of 3 years. The affected nail has a triangular shape and frequently shows dystrophic changes due to repetitive traumatic injuries. The nail plate may be thickened, yellow–brown in color and presents transverse ridging due to intermittent nail matrix damage Citation[17]. Onycholysis is frequent .

Pachyonychia congenita

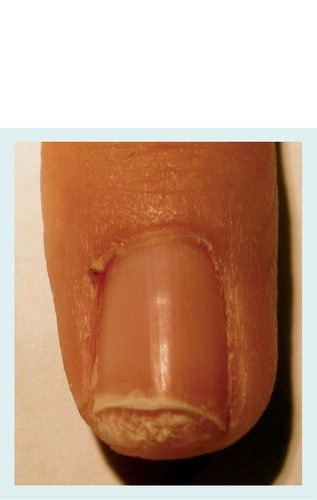

This is a rare condition but must be excluded in children with thick nails. Nail abnormalities are in fact a constant feature and usually develop during childhood Citation[18]. All the nails are thickened, difficult to trim and show an increase in the lateral curvature of the nail plate . Associated findings include follicular hyperkeratosis and palmoplantar keratoderma. Oral lesions are characteristic for type I, while premature dentition and pilosebaceous cysts are observed in type II. When presented with a child with thickening of all nails a careful family history should be taken.

Traumatic onycholysis of the toenails

Traumatic onycholysis of the toenails is very common in adults but can occur in children due to trauma from ill-fitting shoes. The nail plate is detached from the nail bed and appears white because of the presence of air in the subungual space . Onycholysis frequently involves the lateral side of the nail. Although nail dermoscopy may be useful for differential diagnosis, showing specific patterns for onychomycosis, mycology is mandatory to rule out fungal infection Citation[19].

Nail psoriasis

Nail involvement is not rare in children with skin psoriasis and the nails may be the sole localization of the disease. The clinical manifestations of nail psoriasis in children are quite similar to those of adults, with fingernails more commonly affected than toenails. The typical symptom is nail pitting, characterized by deep and irregular punctate depressions on the nail plate surface. Diffuse crumbling of the nail plate is uncommon and must be differentiated from total onychomycosis caused by Candida in immunodepressed patients . Nail psoriasis of the nail bed produces salmon patches, which appear as reddish-orange patches localized in the center of the nail or surrounding an area of onycholysis, onycholysis and subungual hyperkeratosis. Differential diagnosis with distal subungual onychomycosis may be difficult when nail psoriasis involves the nail bed of one or a few digits, producing onycholysis and subungual hyperkeratosis. The presence of splinter hemorrhages suggests psoriasis .

Parakeratosis pustulosa

Parakeratosis pustulosa is a chronic condition that exclusively affects children and usually involves a single finger, most commonly a thumb or an index finger. It is now considered a variant of nail psoriasis in children, as most of the patients will develop psoriasis Citation[20]. The affected digit shows eczematous changes of the hyponychium and pulp associated with mild distal subungual hyperkeratosis and onycholysis . Nail abnormalities are usually more marked on a corner of the nail. The nail plate may occasionally show superficial abnormalities and pitting. Differential diagnosis with distal subungual onychomycosis requires mycology, also taking into account that in children distolateral subungual onychomycosis is often confined to a single fingernail.

Subungual exostosis

Subungual exostosis is a benign bone tumor of the distal phalanx occurring beneath or adjacent to the nail. It is commonly precipitated by trauma and is usually seen on the great toe of young patients. Clinically, subungual exostosis appears as a firm, tender subungual nodule that elevates the nail plate . The nodule may ulcerate or become hyperkeratotic. The diagnosis is confirmed by x-ray examination.

Subungual warts

HPV-induced warts are frequent in children, the most common localizations being the proximal nail fold and the pulp. Warts may localize in the hyponychium, producing a keratotic mass under the nail .

Punctate leukonychia

Punctate leukonychia should be considered in differential diagnosis with white superficial onychomycosis. The nail plate shows small, opaque, white spots that move distally with nail growth and sometimes disappear before reaching the distal nail . It is caused by trauma and is most commonly observed in the fingernails.

Nail fragility

Children’s nails are very thin, as thickening gradually occurs with aging, and are very prone to breakage. The distal nail plate often has an irregular, sharp margin due to breakage of small nail fragments and shows lamellar splitting. Diffuse nail plate fragility can be see on the toenails and may be misdiagnosed as superficial onychomycosis .

Besides these nail diseases that can be differentiated from onychomycosis through a careful clinical examination and mycology, other nail abnormalities are commonly wrongly called onychomycosis as yeast can be isolated from them. These mainly include irritant paronychia (nail sucking). Thumb sucking occurs in approximately 80% of babies and infants, and generally stops by the age of 5 years. The continuous maceration of the periungual tissues by saliva, which also has irritant properties as it is more alkaline, induces inflammation of the periungual tissues and nail plate changes (chronic paronychia). The proximal nail fold shows mild erythema, edema and absence of the cuticle, and the nail plate shows surface abnormalities . Bacteria and yeast easily colonize the moistened new space under the proximal nail fold and are often isolated when microbiology tests are carried out. Isolation of Candida from the fingers with paronychia due to sucking, however, only indicates secondary colonization and not primary invasion.

In the same way, isolation of fungi from the nails or a positive KOH nail examination do not allow diagnosis of onychomycosis if the clinical features are not consistent with fungal nail invasion. A paper published in 2012 reports a 9-month-old child with recurrent onychomadesis of the fingernails associated with erythematous papules and plaques on the dorsum of the hand and wrist Citation[5]. Skin scrapings from the hand cultured T. tonsurans and KOH examination of the nail showed septate hyphae. The authors concluded that onychomadesis was a clinical presentation of fungal nail infection, while it is more likely that periodic nail shedding resulted from nail matrix damage due to inflammation of the skin on the hand induced by the fungus.

Treatment

There are no new data on the treatment of onychomycosis in children, and the drugs available remain the same. Since the condition is very rare, there are no published series, thus a comparison between efficacy and tolerability of the different agents is not possible. The indications for treatment come from the authors’ personal experience, discussion with other nail experts and from cases published in the literature.

Distal subungual onychomycosis caused by dermatophytes involving several digits, particularly in children with tinea pedis and strong familial predisposition, which are therefore prone to recurrences, is an indication for systemic treatment. Possible options include terbinafine tablets, which can be chopped into small pieces and put into meals at a dosage of a quarter of a tablet in children weighing <20 kg and half of one tablet in children weighing 20–40 kg. Above that weight, the dosage is 1 tablet, as for adults. Duration of treatment is 6 weeks for fingernail and 3 months for toenail onychomycosis. Terbinafine is not effective against Candida. A possible alternative for children suffering from onychomycosis is itraconazole, also effective against Candida, prescribed in pulse therapy as for adults, at a dose of 5 mg/kg/day for 1 week per month for 2 months for fingernails and 3 months for toenails. Fluconazole can be used both in dermatophyte and Candida onychomycosis at a dose of 3–6 mg/kg once a week. Duration of therapy is 12–16 weeks for fingernails and 18–26 weeks for toenails.

Duration of treatment with itraconazole and fluconazole may be longer in children with immunodepression and with chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis. Topical therapy, whether associated or not with mechanical or chemical avulsion of the affected nail, is suggested in mild distal subungual onychomycosis of one digit and in superficial onychomycosis. However, none of the available topical drugs for onychomycosis are indicated for use in children. Recurrences of dermatophyte onychomycosis seem to be more common in children than in adults, perhaps due to their strong predisposing factors.

Expert commentary

From our experience and from the data obtained in the literature, few comments are new since our 2009 review. The most common form of onychomycosis we can encounter in our practice is distal subungual onychomycosis due to dermatophyte involving the first toenail or a fingernail, as onychomycosis caused by Candida is more commonly seen by pediatricians or by pediatric dermatologists.

When facing a child with a whitish nail, or a nail detached and uplifted from the nail bed, we should perform a thorough clinical examination, looking at the nail dystrophy with attention, perhaps with the aid of a dermatoscope. The soles and interdigital spaces should be checked for signs of tinea pedis, and a family history of nail diseases should be obtained.

In our experience, onychomycosis is not a common cause of nail disease in children, thus other possible causes should be ruled out in differential diagnosis. Mycology will solve any doubt. The choice of treatment should be based on mycology results and disease severity. Follow-up is mandatory as onychomycosis tends to relapse, more often in children than in adults.

Five-year view

Diagnostic methods could be improved over the next 5 years, with quick and inexpensive techniques made available to every dermatological center. Most topical drugs on the market are not approved for child use, and the possibility of overcoming this problem is the best hope for the future.

Box 1. Differential diagnosis of onychomycosis in children, according to clinical presentation.

• Congenital malalignment of the great toenail

• Pachyonychia congenita

• Traumatic onycholysis

• Nail psoriasis

• Parakeratosis pustolosa

• Punctate leukonychia

• Nail fragility

Key issues

• Onychomycoses in children are rare, and worldwide data confirm a prevalence below 0.5%, except for some countries with a higher incidence, as such as Mexico and Guatemala (>5%).

• Dermatophytes are the most common cause in children with familial predisposition to fungal disease.

• The most difficult task is diagnosis: do not underestimate, but to not overestimate onychomycosis in children!

• Treatment options are the same as for adults, but topical drugs are not approved for use in children.

References

- Raran R. The nail in the elderly. Clin. Dermatol. 29, 54–60 (2011).

- Piraccini BM, Patrizi A, Sisti A, Neri I, Tosti A. Onychomycosis in children. Exp. Rev. Dermatol. 4, 177–184 (2009).

- Zac RI, Café ME, Neves DR, E Oliveira PJ, Barbosa VG. Onychomycosis in a very young child. Pediatr. Dermatol. 26(6), 761–762 (2009).

- Khurana VK, Gupta RK, Pant L, Jain S, Chandra K, Sharma Y. Trichophyton rubrum onychomycosis in an 8-week-old infant. Indian J. Dermatol. Venereol. Leprol. 77(5), 625 (2011).

- Khanna D, Khanna PP, Fitzgerald JD et al. 2012 American College of Rheumatology guidelines for management of gout. Part 2: therapy and antiinflammatory prophylaxis of acute gouty arthritis. Arthritis Care Res. (Hoboken) 64(10), 1447–1461 (2012).

- Vásquez-del Mercado E, Arenas R. [Onychomycosis among children. A retrospective study of 233 Mexican cases]. Gac. Med. Mex. 144(1), 7–10 (2008).

- Pérez-González M, Torres-Rodríguez JM, Martínez-Roig A et al. Prevalence of tinea pedis, tinea unguium of toenails and tinea capitis in school children from Barcelona. Rev. Iberoam. Micol. 26(4), 228–232 (2009).

- Medina Flores J, Bejar Castillo V, Cortez Franco F, Betanzos Huata A. Superficial fungal infections: clinical and epidemiological study in adolescents from marginal districts of Lima and Callao, Peru. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries 3, 313–317 (2009).

- Leibovici V, Evron R, Dunchin M, Westerman M, Ingber A. A population-based study of toenail onychomycosis in Israeli children. Pediatr. Dermatol. 26(1), 95–97 (2009).

- Rodríguez-Pazos L, Pereiro-Ferreirós MM, Pereiro M Jr, Toribio J. Onychomycosis observed in children over a 20-year period. Mycoses 54(5), 450–453 (2011).

- Young LS, Arbuckle HA, Morelli JG. Onychomycosis in the Denver pediatrics population: a retrospective study. Pediatr. Dermatol. (2012) doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.2012.01769.x. (Epub ahead of print).

- Ruiz-Esmenjaud J, Arenas R, Rodríguez-Alvarez M, Monroy E, Felipe Fernández R. [Tinea pedis and onychomycosis in children of the Mazahua Indian Community in Mexico]. Gac. Med. Mex. 139(3), 215–220 (2003).

- Chang P, Logemann H. Onychomycosis in children. Int. J. Dermatol. 33(8), 550–551 (1994).

- Rebell G, Zaias N. Tinea pedis: the child and the family. Pediatr. Dermatol. 16(2), 157 (1999).

- Hay RJ, Baran R. Onychomycosis: a proposed revision of the clinical classification. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 65(6), 1219–1227 (2011).

- Richert B, André J. Nail disorders in children: diagnosis and management. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 12(2), 101–112 (2011).

- Perlis CS, Telang GH. Congenital malalignment of the great toenails mimicking onychomycosis. J. Pediatr. 146(4), 575 (2005).

- Iorizzo M, Vincenzi C, Smith FJ, Wilson NJ, Tosti A. Pachyonychia congenita type I presenting with subtle nail changes. Pediatr. Dermatol. 26(4), 492–493 (2009).

- Piraccini BM, Balestri R, Starace M, Rech G. Nail digital dermoscopy (onychoscopy) in the diagnosis of onychomycosis. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. (2011) doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2011.04323.x. (Epub ahead of print).

- Tosti A, Peluso AM, Zucchelli V. Clinical features and long-term follow-up of 20 cases of parakeratosis pustulosa. Pediatr. Dermatol. 15(4), 259–263 (1998).

Onychomycosis in children

To obtain credit, you should first read the journal article. After reading the article, you should be able to answer the following, related, multiple-choice questions. To complete the questions (with a minimum 70% passing score) and earn continuing medical education (CME) credit, please go to www.medscape.org/journal/expertderm. Credit cannot be obtained for tests completed on paper, although you may use the worksheet below to keep a record of your answers. You must be a registered user on Medscape.org. If you are not registered on Medscape.org, please click on the New Users: Free Registration link on the left hand side of the website to register. Only one answer is correct for each question. Once you successfully answer all post-test questions you will be able to view and/or print your certificate. For questions regarding the content of this activity, contact the accredited provider, [email protected]. For technical assistance, contact [email protected]. American Medical Association's Physician's Recognition Award (AMA PRA) credits are accepted in the US as evidence of participation in CME activities. For further information on this award, please refer to http://www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/category/2922.html. The AMA has determined that physicians not licensed in the US who participate in this CME activity are eligible for AMA PRA Category 1 Credits™. Through agreements that the AMA has made with agencies in some countries, AMA PRA credit may be acceptable as evidence of participation in CME activities. If you are not licensed in the US, please complete the questions online, print the AMA PRA CME credit certificate and present it to your national medical association for review.

Activity Evaluation: Where 1 is strongly disagree and 5 is strongly agree

1. You are seeing a 5-year-old boy with a chief complaint of nail abnormalities. As you begin to evaluate this child, what should you consider regarding the epidemiology and etiology of onychomycosis among children?

□ A The prevalence of onychomycosis among children is less than 0.5%

□ B The causative organisms of onychomycosis differ in tropical vs temperate countries

□ C Trichophyton tonsurans is the most important cause of onychomycosis among children

□ D Microsporum canis is the mostimportant cause of onychomycosis among children

2. What should you consider regarding the clinical features of onychomycosis and fungal infections among children as you examine this patient?

□ A Tinea pedis is usually limited to the interdigital space and is severe among children

□ B Most cases involve the entire nail

□ C Most cases involve only a single toenail

□ D The color of the nail in onychomycosis is invariably white

3. What should you consider regarding other conditions that might mimic onychomycosis in this case?

□ A Congenital malalignment of the great toenail is usually evident by age 3 months

□ B Pachyonychia congenita involves all the nails

□ C Traumatic onycholysis is characterized by a lack of changes to the color of the nail plate

□ D Toenails are more commonly affected than fingernails in cases of psoriasis

4. You diagnose onychomycosis in this child. What should you consider regarding treatment of this condition?

□ A Onychomycosis limited to the distal subungual area does not merit treatment

□ B Onychomycosis in several digits is an indication for systemic treatment

□ C Terbinafine should be avoided among children

□ D Several topical drugs are indicated for the treatment of superficial onychomycosis among children