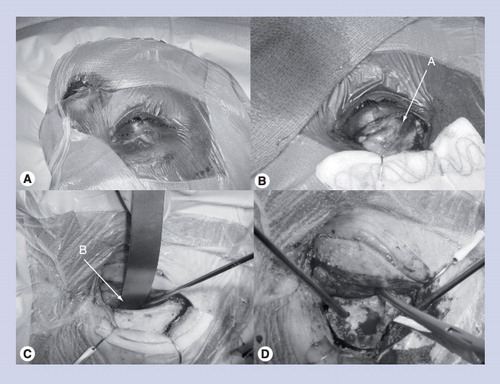

Please note that the images are compiled from different patients. (A) Incision is marked in a crease in the upper eyelid and extends lateral to, but not involving, the lateral canthal ligament. (B) Image is shown with orbital septum preserved and eyelid flap retracted by fishhooks after utilizing a combination of sharp and blunt dissection. (C) Subperiosteal dissection is performed while preserving the orbital contents. (D) Image showing one-piece craniotomy-orbital ridge osteotomy being elevated after osteotomies are made with a craniotome.

A: Orbital septum; B: Orbital ridge.

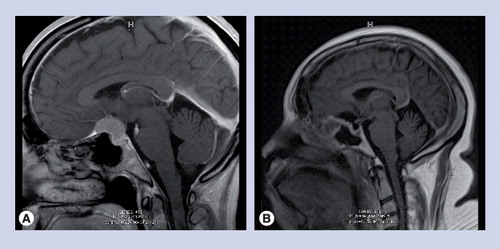

(A) Preoperative sagittal MR contrast-weighted scan demonstrating tuberculum sella meningioma. (B) Postoperative sagittal MR contrast-weighted scan demonstrating gross total resection.

The push in modern neurosurgery has been for the development of minimally invasive approaches for cranial base lesions, as an alternative to the larger, more complex skull base approaches. The introduction of endonasal endoscopic approaches provided a minimally traumatic approach to lesions in the midline skull base from the cribiform plate to the sella and clivus. The keyhole craniotomies, such as the supraorbital craniotomy, have provided a similar solution for select lesions in all three cranial fossae. Concurrently, with an improved appreciation on postoperative wound healing and cosmesis, the current trend is to also take advantage of natural orifices (endonasal techniques) and skin creases. The transpalpebral incision – borrowed from ocular plastics – has been paired with the supraorbital craniotomy as a keyhole approach. In this brief article, we discuss current trends in minimally invasive approaches and considerations in using the transpalpebral approach for a variety of tumors.

The evolution of minimally invasive approaches: the concept of the keyhole craniotomy

In the very nascent stages of neurosurgery, the primary surgical treatment of intracranial lesions was via large craniotomies. This, in part, was necessary for several reasons. At the time, diagnostic techniques were poorly developed (i.e., computed topography); hence, the accurate anatomic localization of lesions was inaccurate due to the radiographic tools available at the time. As a consequence, craniotomies had to be large in order to find and visualize the target lesion. In addition, initial methods of illumination were unsophisticated and the instruments initially used were not designed for microsurgery, but for general surgery.

In recent decades, the field has seen technological advancements and the discovery of fundamental anatomic principles. Improvements in visualization with the operating microscope and the introduction of refined instrumentation have led to the evolution of microneurosurgical techniques. Concurrently, the advent of MRI and the introduction and widespread adoption of MR-based neuronavigation have improved the intraoperative targeting of lesions by facilitating more efficient microsurgical dissection.

The recent push in the field of neurosurgery has been for minimally invasive approaches (open and endoscopic) to target deep-seated pathology in all three cranial fossae. While endoscopic approaches have been introduced to target selected pathology in the sella and parasellar regions, the concept of the ‘keyhole’ craniotomy was introduced by Pernezcky and colleagues for remaining lesions in the cranial space Citation[1]. This is based on the concept that a smaller, more tailored craniotomy can provide equivalent, if not superior, visualization to larger cranial base approaches, while minimizing manipulation of neurovascular structures and with limited retraction needed for visualization. The simple analogy is that an entire room can be visualized through a peep-hole (as opposed to opening the entire door), as long as the viewer changes their angle of view through the hole. The keyhole craniotomy essentially implies that craniotomies should be restricted in the extent of neurovascular tissue damage, but appropriately designed such that the surgeon can take advantage of appropriate anatomic windows and triangles to access deep-seated lesions. As a result, we have seen a stepwise reduction in craniotomies necessary for deep lesions.

Lesions in the anterior cranial fossa, parasellar region and interpeduncular cistern can be difficult to resect due to surrounding neurovascular structures. Successful resection of lesions in these areas is dependent on selecting a microsurgical approach that places the target lesion at the ideal angle of attack in relation to the surrounding structure, while also allowing gravity to aid in brain retraction/manipulation. A myriad of approaches to the above-named regions are available – ranging from anterior/subfrontal to antero-lateral (trans-sylvian) to postero-lateral (trans-petrous, trans-tentorial) Citation[2–5]. Each approach is associated with its own set of angles of exposure, advantages and complications. For selected lesions, the anterior subfrontal trajectory often provides a shortened working distance, while also allowing the surgeon to work between neurovascular structures, as opposed to across them (such as in the trans-sylvian approaches). When initially described, the subfrontal approach was performed via a large frontal craniotomy exposing the entire frontal lobe, although only exposure of the basal frontal lobe was necessary.

The introduction of the supra-orbital craniotomy: the concept of a tailored craniotomy

A variant of the frontal craniotomy, the supraorbital craniotomy, was initially described by Jane et al.Citation[6]. Performed via a traditional scalp flap positioned behind the hairline, this craniotomy was centered antero-laterally around the orbital roof/anterior fossa floor, with limited exposure of the frontal pole. This approach was based on the concept of an optimally designed craniotomy that provides anatomic exposure equivalent to that of an anterior subfrontal approach. With or without the additional orbital osteotomy, the supra-orbital craniotomy is primarily indicated for those lesions either in the anterior cranial fossa (i.e., smaller olfactory groove meningiomas), parasaellar region (i.e., pituitary macroadenomas, craniopharyngiomas and anterior communicating artery aneurysms), interpeduncular cistern (i.e., basilar apex aneurysm) and proximal sylvian fissure (i.e., M1/2 aneurysms). Since its original description, numerous modifications of this approach have been described. A popular modification has been the addition of an orbital osteotomy Citation[7,8]. Providing increased visualization and thought to limit frontal lobe retraction while increasing working space, this modification has been employed for either lesions reaching several centimeters above the anterior clinoid or high-riding basilar apex aneurysms. In addition to modifying the osteotomies, changes have been suggested to make a more cosmetically appealing incision (ranging from a supraciliary incision, to a transciliary incision, to an upper blepharoplasty incision) Citation[8–10].

Improving cosmesis & patient perception: the transpalpebral incision

With the impetus for minimally invasive approaches and trans-nasal endoscopic resection of midline cranial base lesions, the modern neurosurgeon has been increasingly attuned with incision size/location and postoperative patient self-perception as a result of cosmetic outcomes. An incision that minimizes pain and heals well is thought to improve patient self-perception and postoperative quality of life. The supraorbital craniotomy, while initially introduced through a traditional and larger scalp flap, was popularized with an transciliary (eyebrow) incision Citation[1,11–14]. Such incisions are appealing due to the minimal tissue manipulation required. In addition, a transciliary incision provides direct access to the region of bone to be removed. However, while associated with overall acceptable wound healing, the incision is associated with the theoretical risk of alopecia and frontalis palsy, both of which can be cosmetically disfiguring. In addition, an incision made in the eyebrow is typically not well hidden or appreciated in females in general, or patients with thinning eyebrows. Moreover, a direct forehead or brow incision may be risky in patients with skin types prone to hypertrophic scarring.

In an effort to provide a cosmetically pleasing incision, the eyelid incision – or transpalpebral approach – has been introduced Citation[8–10]. Commonly used by ocular plastic surgeons for blepharoplasty and orbital tumors, this incision takes advantage of a natural skin fold Citation[10,15,16]. The incision is performed in a natural crease in the patient’s superior eyelid; this crease is identified by having the patient open and close their eyes immediately prior to anesthesia induction . Proven by its use in facial plastic surgery, we, in addition to several other groups, have adopted its use for performing supraorbital craniotomies. The incision is appealing in that it provides direct access to the orbital ridge and is associated with less soft-tissue dissection. Due to the bony exposure provided, we feel that this incision is most suited for performing a supraorbital craniotomy with an orbital osteotomy. Another theoretical advantage of this incision, over the transciliary incision dissection plane taken to the orbital ridge, is that the risk of frontalis injury is minimized. Ultimately, as a result of the transpalpebral incision, our preliminary experience suggests that this incision provides good cosmetic outcomes and is well suited for performing anterior subfrontal approaches.

Clinical applications of the transpalpebral incision

We have primarily used the transpalpebral approach to resect tumors in the parasellar region, in addition to repairing cerebrospinal fluid leaks in the anterior cranial fossa. From the oncologic standpoint, this incision, when used for a supraorbital craniotomy with an orbital osteotomy, provides adequate visualization for lesions along the tuberculum sella, planum sphenoidale and suprasellar cistern. The removal of the orbital ridge increases visualization to approximately 2–3 cm above the anterior clinoid. While performed via a relatively small incision, the craniotomy provides adequate working space. Tumors resected range from planum sphenoidale meningiomas to pituitary macroadenomas . Aside from routine techniques to obtain brain relaxation, we employ several techniques to overcome the perceived limited working space. A lumbar subarachnoid drain can be placed where the tumor may limit early access to critical cisterns, which need to be opened for brain relaxation. In addition, the use of angulated instruments, such as transphenoidal instruments and angled curettes, permits the surgeon to work around corners and neurovascular structures. Extreme caution should be practiced; the surgeon should have a thorough understanding of the anatomy prior to using angled instruments outside their direct visualization. To supplement microscopic illumination, we also typically use an endoscope for the final stages of tumor dissection to better visualize around otherwise obstructive anatomic structures. Overall, we have found the transpalepebral incision to be great for appropriately selected tumors where limited complex dissection is necessary and tumor resection can proceed through a primary microsurgical corridor.

Conclusion

Recognizing the importance of minimizing neurologic morbidity by limiting soft-tissue manipulation, increasing interest has been placed on minimally invasive approaches (open and endoscopic) to pathology in the anterior cranial fossa and sellar/parasellar region. The concept of the keyhole craniotomy was introduced based on the notion that a smaller tailored craniotomy can be designed to visualize deeper lesions; the supraorbital craniotomy was the first such craniotomy described. Initially performed via a transciliary incision, a similar craniotomy combined with an orbital osteotomy can now be performed via a transpalpebral incision. We have found that this incision, which is cosmetically pleasing, can be employed for a variety of tumors in the anterior cranial fossa, parasellar region and interpeduncular cistern. Safe application of this approach requires not only microsurgical experience to work in a limited working space, but also the use of adjuncts, such as angulated instruments and endoscopes. For appropriately selected lesions that do not require complex neurovascular dissection, our experience demonstrates that this is an approach that can be used for safe and effective tumor resection.

Financial & competing interests disclosure

The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

References

- Reisch R, Perneczky A. Ten-year experience with the supraorbital subfrontal approach through an eyebrow skin incision. Neurosurgery57, 242–255; discussion 242–255 (2005).

- Al-Mefty O, Ayoubi S, Kadri PA. The petrosal approach for the total removal of giant retrochiasmatic craniopharyngiomas in children. J. Neurosurg.106, 87–92 (2007).

- Al-Mefty O, Ayoubi S, Kadri PA. The petrosal approach for the resection of retrochiasmatic craniopharyngiomas. Neurosurgery62, ONS331–ONS335; discussion ONS335–ONS336 (2008).

- Figueiredo EG, Deshmukh P, Zabramski JM, Preul MC, Crawford NR, Spetzler RF. The pterional-transsylvian approach: an analytical study. Neurosurgery59, ONS263–ONS269; discussion ONS269 (2006).

- Figueiredo EG, Deshmukh P, Zabramski JM, Preul MC, Crawford NR, Spetzler RF. The pterional-transsylvian approach: an analytical study. Neurosurgery62, 1361–1367 (2008).

- Jane JA, Park TS, Pobereskin LH, Winn HR, Butler AB. The supraorbital approach: technical note. Neurosurgery11, 537–542 (1982).

- Andaluz N, van Loveren HR, Keller JT, Zuccarello M. The one-piece orbitopterional approach. Skull Base13, 241–245 (2003).

- Boaehene K, Lim M, Chu E, Quinones-Hinojosa A. Transpalpebral orbitofrontal craniotomy: a minimally invasive approach to anterior cranial vault lesions. Skull Base20, 237–244 (2010).

- Andaluz N, Romano A, Reddy LV, Zuccarello M. Eyelid approach to the anterior cranial base. J. Neurosurg.109, 341–346 (2008).

- Chu EA, Quinones-Hinojosa A, Boahene KD. Trans-blepharoplasty orbitofrontal craniotomy for repair of lateral and posterior frontal sinus cerebrospinal fluid leak. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg.142, 906–908 (2010).

- Jallo GI. Eyebrow surgery. J. Neurosurg. Pediatr.1, 144; author reply 144 (2008).

- Jallo GI, Bognar L. Eyebrow surgery: the supraciliary craniotomy: technical note. Neurosurgery59, ONSE157–ONSE158; discussion ONSE157–ONSE158 (2006).

- Ramos-Zuniga R: The trans-supraorbital approach. Minim. Invasive Neurosurg.42, 133–136 (1999).

- Ramos-Zuniga R, Velazquez H, Barajas MA, Lopez R, Sanchez E, Trejo S. Trans-supraorbital approach to supratentorial aneurysms. Neurosurgery51, 125–130; discussion 130–121 (2002).

- Kung DS, Kaban LB. Supratarsal fold incision for approach to the superior lateral orbit. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endod.81, 522–525 (1996).

- Lane CM. Cosmetic orbital surgery. Eye20, 1220–1223 (2006).