Abstract

Schizophrenia is a disorder with an estimated suicide risk of 4–5%. Many factors are involved in the suicidal process, some of which are different from those in the general population. Clinical risk factors include attempted suicide, depression, male gender, substance abuse and hopelessness. Biosocial factors, such as a high intelligence quotient and high level of premorbid function, have also been associated with an increased risk of suicide in patients with schizophrenia. Suicide risk is especially high during the first year after diagnosis. Many of the suicides occur during hospital admission or soon after discharge. Management of suicide risk includes both medical treatment and psychosocial interventions. Still, risk factors are crude; efforts to predict individual suicides have not proved useful and more research is needed.

Schizophrenia

Schizophrenia is a devastating psychiatric disorder affecting approximately 1% of the population worldwide during a lifetime. The onset of the illness occurs relatively early in life, usually in the late teens or early adulthood, and most patients have long-lasting adverse effects. Schizophrenia is a clinical syndrome diagnosed on the basis of symptom profiles, and is characterized by a constellation of symptoms of psychosis, such as abnormalities in the perception or expression of reality, as well as negative symptoms, such as affective flattening and avolition. Cognitive deficits are also usually present, and the symptoms must have persisted continuously for a least 6 months: however, schizophrenia cannot be diagnosed if symptoms of mood disorder are present or the symptoms are the direct result of a medical condition or substance abuse (Box 1)Citation[201].

The specific causes of schizophrenia are not known and combinations of several factors are likely to be involved. Genetic factors play a major role in the development of the disease Citation[1], and environmental factors are also of importance. These latter factors include a history of obstetric complications, such as asphyxia Citation[2] and prematurity Citation[3]. Advanced paternal age is also considered to be a risk factor Citation[4], and birth during the spring and late winter also increases the risk Citation[5]. Prenatal viral infections Citation[6], serious viral infections of the CNS during childhood Citation[7], migrant status and urban rearing Citation[8], and a lifetime history of cannabis use Citation[9] are other well-known risk factors.

Contrary to previous interpretations, the incidence and prevalence of schizophrenia show marked variation between sites. For example, migrants have an increased incidence and prevalence of schizophrenia, and exposures related to urbanicity, economic status and latitude are also associated with various frequency measures Citation[10]. Men have a higher risk than women Citation[11], and a recent review concluded that men have a 40% higher incidence of schizophrenia than women Citation[12].

Suicide

Suicide is defined as a self-inflicted death with evidence that the person intended to die (Box 2)Citation[13]. Suicide is among the leading causes of premature death in the world and it is estimated that approximately 1 million people die by suicide every year Citation[202]. Suicide rates vary according to region, gender, age, time and ethnic origin, and also according to death registration practices. The annual suicide rate in the world is 14.5 out of 10,0000 (in 2000), which is equal to one suicide every 40 s. Suicide is approximately three- to four-times more common in men than in women Citation[202]. Suicide rates vary between different regions, and underestimation of suicide rates is common due to under-reporting, lack of epidemiological data and misclassification Citation[14]. It has been estimated from psychological autopsies that more than 90% of those dying by suicide have a diagnosable psychiatric disorder at the time of death, and approximately 60% of the suicides occurred in relation to depressive disorders. Other psychiatric disorders at high risk for suicide include schizophrenia, substance abuse, alcoholism and personality disorders Citation[15].

Suicide in schizophrenia

Suicide is a major cause of death among patients with schizophrenia and was already described by Eugen Bleuler as early as 1911 as “the most serious of schizophrenic symptoms” Citation[16]. The lifetime prevalence of suicide in patients with schizophrenia has been estimated to be ten-times higher than among the average population Citation[17]. Earlier research has suggested suicide rates of up to 13% among patients with schizophrenia Citation[18], but more recent studies, taking into account the variable suicide risk during a life span – that is, a higher risk close to illness onset and thereafter a declining risk – report a lifetime suicide mortality of 4–5% Citation[19,20]. Compared to the suicide risk in the general population, a relatively higher suicide risk in schizophrenia has been found in younger age groups Citation[21]. Over time, a reduction in the suicide rate among patients with schizophrenia has been reported, similar to that in the general population Citation[22], although a recent meta-analysis suggests that the mortality gap between the general population and patients with schizophrenia has increased in recent decades Citation[23].

The excess mortality in schizophrenia is caused more by natural than unnatural causes of death, with cardiovascular disease and cancer being the most common Citation[21,24]. However, the specific causes of death giving rise to excess mortality were suicides in males and cardiovascular disease in females in a Swedish population-based study Citation[21]. Aside from suicide, unnatural causes of death, such as accidents, are more common among patients diagnosed with schizophrenia than in the general population Citation[21,25,26].

Despite the high suicide frequencies in patients with schizophrenia when compared with the general population, the real number of patients eventually dying by suicide is low, indicating the importance of external risk factors and a predisposition to suicidal behavior that is independent of the main psychotic disorder. For example, an acute social crisis in a patient with schizophrenia appears to be the most proximal stressor leading to suicidal behavior. Several factors influence this interaction: personality traits, such as aggression and impulsivity, may be important Citation[27,28], in addition to gender, genetic and environmental factors Citation[27,29].

The clinical assessment of suicide risk is a difficult and demanding task in everyday clinical work, given the many factors involved in the suicidal process and the limited specificity of clinical suicide predictors Citation[18]. However, identification of risk factors is necessary for predicting and preventing suicide, although few clinical suicide assessment tools for schizophrenic patients live up to reasonable expectations Citation[30].

Risk factors for suicide in schizophrenia

The risk of suicide in patients with schizophrenia is considered to be highest in the early course of the illness, especially within the first year of illness Citation[20,31,32]. Studies with a first-episode cohort and covering a period close to the onset of illness usually have higher estimates of excess mortality from suicide than studies with longer periods of follow-up Citation[26]. However, hitherto, most studies have been retrospective in nature and there is a demand for prospective studies. In a recent prospective Finnish study, these earlier results were confirmed, finding that a large majority of the suicides took place during the first years of the illness Citation[33]. White ethnicity has been associated with a higher suicide risk Citation[34]. To date, the results from meta-analyses are inconclusive as to how the age at onset of symptoms affects the suicide risk Citation[34], although two recent studies found a higher suicide risk in patients falling ill at older ages Citation[32,35]. One explanation for the increased risk of suicide associated with increased age at onset of illness might be the stress these patients face, having established themselves during early adult years with a family and occupation, and suddenly facing the deterioration in function and health that the disorder brings.

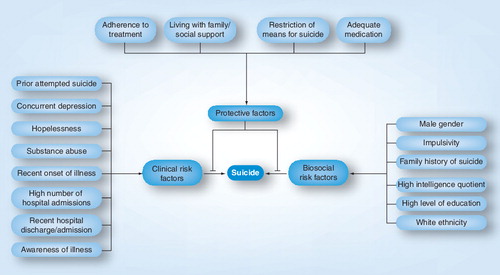

Despite the risk of suicide being highest in the early phases of the illness, the risk appears to accumulate over a long period of time Citation[36], and it is considered to be high at any point in time during the course of the illness Citation[37]. The suicide risk is especially high in relation to hospitalization, which stresses the importance in clinical practice of paying extra attention during this period. It has been estimated that a third of the suicides among patients with schizophrenia occur during admission or within 1 week after discharge from hospital. Several studies have reported a peak of suicide risk during these periods Citation[24,38,39], indicating the importance of an immediate assessment of the suicide risk after admission and proper follow-up and out-patient treatment immediately after discharge from hospital. However, a recent population-based study reports that the suicide risk for schizophrenia was relatively constant during the first year following discharge from hospital Citation[40]. The number of psychiatric admissions itself has been associated with a higher risk of suicide and has been suggested to be indicative of the severity of illness Citation[38,41,42]. A recent study reported a relationship between post-discharge suicide and the psychiatrists’ gender and age, indicating a potential need for quality improvement among subgroups of mental health professionals. Demand for research into this topic has been made Citation[43]. During the last few decades there have been changes in health systems, with significant reductions in in-patient capacity. These changes have been suspected to be an important factor in the rising mortality seen in patients with schizophrenia Citation[44,45]. However, the effect of the reduction in in-patient capacity on the suicide rate remains unclear due to conflicting results Citation[46]. summarizes the important risk and protective factors for suicide in schizophrenia.

The articles in this review have been searched for on PubMed using the keywords ‘suicide AND schizophrenia’. The inclusion of relevant papers has been made by choice of the authors on the basis of their expertise in the field. Hence it is not a comprehensive review, but rather a selective review based on the extensive clinical experience of the authors.

Attempted suicide in schizophrenia

In most studies, a history of self-harm or suicide attempts is the strongest risk factor for suicide Citation[47]. A history of attempted suicide significantly increases the risk of suicide among patients with schizophrenia Citation[34,48,49], and is reported to be the strongest clinical risk factor for suicide Citation[49]. Compared with other psychiatric disorders coexistent with a suicide attempt, schizophrenia substantially influences the overall risk and temporality for completed suicide Citation[50]. A recent study suggests that attempted suicide is an especially strong risk factor for suicide among male schizophrenic patients Citation[48].

Attempted suicide is common among patients with schizophrenia, with estimates ranging from 20 to 40% Citation[46]. The methods used are often more violent and lethal than suicide attempts in the general population, suggesting a higher intent to die Citation[51,52]. Depression is an important risk factor for attempted suicide in schizophrenia Citation[53,54]. One review examining risk factors for deliberate self-harm (i.e., attempted suicide and similar potentially harmful acts in which motives other than dying may have been more prominent) found five significant variables: past or recent suicide ideation, previous deliberate self-harm, past depressive episodes and a higher mean number of psychiatric admissions Citation[55]. Suicidal ideation of a past and recent nature has also been considered a risk factor for suicide, although the conclusions drawn from studies examining suicide threats as a predictor for future suicide have been contradictory Citation[34].

Concurrent depression & suicide risk

More than half of all people dying by suicide have a diagnosable depression at the time of suicide Citation[49], and intermittent depressive disorders are common among patients with schizophrenia Citation[56]. Having a depressive disorder is suggested to act as a trigger for suicidal behavior in vulnerable patients with schizophrenia Citation[57], and a history of past and present depressive disorders shows a strong association with suicide Citation[34]. Therefore, the assessment of symptoms of depression is important for these patients, and also, in the event of a depressive disorder, sufficient treatment of the depression. However, depression can easily be missed in patients with schizophrenia because symptoms of depression can be confused with negative symptoms of psychosis or side effects of neuroleptic medication Citation[58]. Along with a coexisting depression, the feeling of hopelessness has been shown to be an important risk factor for suicidal behavior in schizophrenia Citation[59], and the importance of hopelessness as a risk factor remains even without a concurrent depression Citation[56].

Comorbid substance abuse & suicide risk

Substance abuse is common in individuals with schizophrenia, particularly in men. Nearly 50% of patients with schizophrenia have a substance-abuse-related disorder at some point during their illness. In a review, drug abuse was reported to considerably increase the risk of suicide Citation[34]. These authors could not find any association between alcohol abuse and suicide risk. Limosin and coworkers reported that illicit drug use, in contrast to alcohol abuse, was one of four significant independent risk factors for suicide Citation[60]. Substance abuse has also been associated with impulsiveness and suicidality Citation[61]. Heilä et al. reported that alcoholism was found among a fifth of suicide victims with schizophrenia, and the proportion of comorbid alcohol abuse was highest among middle-aged men Citation[37].

Besides alcohol, cannabis is the most frequently abused drug among patients with schizophrenia Citation[62]. Drug abuse, particularly of cannabis, is frequent among patients with first-episode schizophrenia, and the age of onset of schizophrenia appears to be lower among cannabis abusers compared with both cannabis non-abusers and alcohol abusers Citation[63,64]. Cannabis use appears to be associated with an increased risk for schizophrenia Citation[65].

Comorbidity between schizophrenia and substance abuse could lead to consequences such as noncompliance with medication, loss of control, violence and economic problems. As a result, worsened psychotic symptoms and increased use of psychiatric services has been reported in schizophrenic patients with concurrent substance abuse. However, the studies have reported conflicting results. Miller and coworkers reported that cannabis use was a risk factor for nonadherence to medication and dropout from treatment Citation[66]. Cantwell reported that substance-abusing psychotic patients were younger, more likely to be men and had an earlier age at psychosis onset Citation[67]. No marked difference was found with regard to symptoms, social function and service use compared with nonabusive schizophrenic patients. Nor did Gut-Fayand and coworkers report any marked effects on symptoms, social functioning and service use between substance-abusing and non-abusing patients with schizophrenia Citation[61]. Zisook et al. reported that schizophrenic patients with a history of substance abuse did not have more symptoms and were not more impaired than schizophrenic patients who had never abused drugs Citation[68]. However, an association has been reported between dual diagnosis and homelessness Citation[69,70]. Other studies report that patients with severe mental illnesses who had substance abuse spent more days in hospital Citation[71], have higher rates of anxiety, depression and hallucinations Citation[72] and were more likely to report aggression or hostile behavior Citation[73]. An association between violent crime and substance abuse has also been reported among patients with schizophrenia Citation[74,75].

Psychosocial factors & suicide risk

Several personal and social factors have been found to influence the risk of suicide among patients with schizophrenia. A high intelligence quotient has been associated with an increased risk of suicide Citation[76,77], as well as a high level of education Citation[34,35,78]. Good school performance at the age of 16 years has been associated with an increased risk of suicide (before the age of 35 years) in persons who develop psychosis, whereas in persons who do not develop psychosis, it is associated with a lower suicide risk Citation[79]. Higher education may contribute to a greater sense of loss due to the illness and may, therefore, increase the suicide risk Citation[80]. The concept of insight – that is, the patient’s awareness of the disease and the need for treatment, as well as the consequences of the disease – have been thoroughly investigated and suggested to be associated with an increased risk of suicide. However, this association is only valid if the awareness leads to hopelessness Citation[81,82]. These findings suggest that a person with a high level of premorbid functioning facing the deterioration of health following the disease has an increased risk of suicide. An assessment of the awareness of illness, along with feelings of hopelessness, is, therefore, of vital importance when evaluating the suicide risk. Compliance with treatment, which is related to the patient’s awareness of the need for treatment, is crucial over time to reduce the risk of attempted suicide Citation[83,84] and suicide Citation[85,86]. Consequently, poor adherence to treatment is an important risk factor for suicide Citation[34]. Personality traits such as aggression and impulsivity have been associated with suicidal behavior in psychiatric patients when ratings of the objective severity of the depression or psychosis have also been taken into account Citation[27]. In patients with schizophrenia, an association between impulsivity, but not with aggression, and suicidal behavior has been reported Citation[56,87]. Other social factors, such as living alone or not living with one’s family, and the experience of a recent loss, have been associated with an increased risk of suicide, indicating the importance of social support; subsequent living with one’s family might be a protective factor against suicide. Being married or single was not associated with an increased risk of suicide in a recent meta-analysis Citation[34].

Gender & suicide risk in schizophrenia

Most studies report that male patients with schizophrenia have a higher risk for suicide than females Citation[34,88]. In the general population, the risk for suicide is higher in men than in women in most countries Citation[89]. One exception is China, where the suicide rates for men and women are equal, or even higher for women Citation[90]. In general, the suicide rate is approximately three- to four-times higher for men than for women Citation[45,90–92]. The gender difference seems to be less marked among patients with schizophrenia. In a review, the ratio for men compared with women was 1.57 Citation[34]. Perhaps the gender difference in the suicide rate is mainly driven by the effect of gender in the general population without a history of psychiatric disorders. Severe clinical conditions can override some, but not all, of the gender effect. That might provide the explanation as to why some studies found no gender difference in suicide among schizophrenic patients Citation[35,91]. However, the suicide standardized mortality rate of schizophrenic patients is equal or higher for women compared with men in some studies Citation[21,24,25,60].

Women who die by suicide appear to be older than men who die due to the same cause. This may be related to the later age at the onset of illness in females Citation[93]. It is also possible that schizophrenia affects the sexes differently. Salokangas found only small differences in clinical conditions between the sexes Citation[94]. However, with regard to social conditions and work adjustments, men performed poorer than women diagnosed with schizophrenia. Important predictive factors for suicide in female, but not male, schizophrenic patients are a history of sexual abuse, intimate partner abuse and loss of children Citation[95], suggesting that risk factors might differ between the genders.

The methods of suicide vary between the genders. Men often use more violent methods than women, such as hanging, shooting and jumping from high places Citation[36,93]. Young age (16–32 years) appears to increase the risk of violent suicide in both sexes Citation[37].

Psychotic symptoms & suicide risk in schizophrenia

Schizophrenia is not a homogeneous illness, but a syndrome that comprises of a wide variety of symptoms; consequently, there are substantial differences in clinical symptom presentations between patients, despite the need for certain core symptoms to make the diagnosis. The question is whether any of these symptoms are related to suicidal behavior. Depression and hopelessness, which are not core symptoms of schizophrenia, are important risk factors and have been discussed earlier. Depression-related symptoms, such as agitation or motor restlessness, as well as fear of mental disintegration Citation[34] and anxiety Citation[96], have been associated with suicide. Positive (hallucinations, delusions and disorganization) and negative symptoms of schizophrenia have been investigated in association with suicide risk in several studies, and the results have been conflicting. In a meta-analysis, Hawton and coworkers reported that studies investigating command hallucinations and suicide risk showed significant heterogeneity with both positive and negative associations Citation[34]. No overall association with suicide risk was reported. However, several studies reported association between positive symptoms and suicide risk Citation[77,97], as well as attempted suicide in the context of command hallucinations Citation[98]. An association between the total number of positive symptoms and suicide risk has also been reported Citation[76].

Fewer studies have investigated the relationship between suicide risk and negative symptoms in schizophrenia, and any association remains unclear. In summary, the risk factors for suicide in schizophrenia appear to be less associated with typical core symptoms of psychosis, such as delusions and hallucinations, but more with depressive symptoms, such as agitation, hopelessness and feelings of worthlessness Citation[34].

Biomarkers of suicide risk in schizophrenia

The biology of suicide includes a broad area of research comprising, among other things, studies on neurotransmitters, neuroendocrinology, neuroimaging and genetics. Most of the studies involving biological research on suicide have focused on patients with mood disorders.

Low concentrations of the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) serotonin metabolite 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA) have been associated with attempted suicide and death by suicide among patients with depressive disorders Citation[99–101]. The relationship between the major dopamine metabolite homovanillic acid in the CSF and suicidal behavior has also been investigated, but without firm evidence for an association Citation[102]. An association between a low CSF homovanillic acid:5-HIAA ratio and suicidal behavior and intent has been reported Citation[103–105]. However, most of these patients were diagnosed with depressive disorders, and only a few had a diagnosis within the psychotic spectrum. Suicide attempters in general are more impulsive than psychiatric controls Citation[27], and low concentrations of CSF 5-HIAA have been associated with aggressiveness from a lifetime perspective, as well as with lethality of suicide attempts Citation[106,107]. Serotonin dysfunction, as measured by CSF, has been linked to traits of aggressiveness and depression, which may be clinical mediators of suicidal behavior, an important risk factor for suicide in schizophrenia Citation[108]. However, to date, studies analyzing suicidal behavior and CSF monoamine metabolites in patients with schizophrenia are few in number, and, in the largest study, no association was reported Citation[109]. Platelet serotonin and serum cholesterol concentrations have been associated with suicidality in patients with their first episode of psychosis and have been suggested to be useful biological markers of suicidality Citation[110].

Dysfunctions in the hypothalamo–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis, as measured by the dexamethasone suppression test, have been reported to have predictive power for suicide in depressive disorders Citation[111]. Some studies have reported an association between dysfunction of the HPA axis and suicidal behavior in patients with schizophrenia Citation[58,112], whereas others have failed to detect such a relationship Citation[113,114].

Epidemiological studies investigating genetic influences have suggested that there is a genetic basis to suicidal behavior Citation[115]. It has been suggested that these genetic influences are specific and independent from the genetic factors implicated in predisposition to psychiatric disorders in general Citation[116]. Suicide and psychiatric illness in relatives are general risk factors for suicide Citation[77], and the effect of a family history of suicide is independent of the familial cluster of mental disorders Citation[117,118]. Genetic association studies on suicide have mainly focused on serotonin-related genes. Meta-analyses have reported an association between variants in the serotonin transporter Citation[119] and the tryptophan hydroxylase 1 (TPH1) genes Citation[120], although the latter was not associated within patient groups, suggesting that the association between the TPH1 genes and suicide behavior was confounded by association with the disease Citation[121]. With regard to another frequently analyzed gene, the serotonin transporter 2A (HTR2A), there seems to be no firm evidence for an association Citation[120,122]. In the area of less well-studied genes, a report analyzing patients with schizophrenia found an association between some genes involved in the HPA axis and suicidal behavior Citation[123]. Another study reported differences in expression of the DARPP-32 gene, which is involved in dopamine, and possibly serotonin, regulation, between schizophrenic patients who died by suicide and due to other causes Citation[124]. However, the specificity of these findings is very low, and a lot of work remains to be done until clinical benefits can be gained Citation[125]. The last decade has seen an increasing use of neuroimaging in schizophrenia research on structural changes in the brains of patients. An association between structural changes in areas such as the left orbitofrontal and superior temporal gyrus Citation[126], as well as in the inferior frontal volume Citation[127], and suicidal behavior has been reported. However, more studies are needed to expand our knowledge of biological mechanisms underlying suicide in schizophrenia, and the clinical implications of these findings are yet to be investigated.

Prevention & treatment of suicide risk in schizophrenia

Reducing the risk of suicide in patients with schizophrenia is of vital importance, but it is challenging because of the many factors involved. Suicide research has produced numerous false-negatives and far too many false-positives to be useful in identifying which schizophrenic patients require extraordinary suicide prevention precautions Citation[18]. However, the identification of risk factors is important for initiating preventive measures. The reduction of the number of new cases of individuals committing suicide is the ideal method of protection and requires modification of a wide range of social, economic and biological conditions to prevent members of a population from becoming suicidal. This might include addressing factors such as reduction of poverty and promotion of general health Citation[128]. Restriction of the means for suicide is an important part of preventive strategies and has been shown to be effective in the reduction of suicide Citation[129]. Suicide prevention also includes general preventive strategies, such as restricted availability of alcohol and drugs, barriers at bridges and observation by cameras at railways, as well as suicide risk management for the specific individual. This involves the use of appropriate treatments including medication, psychosocial interventions and psychotherapy Citation[130]. Early detection programs that bring patients with symptoms of psychosis into treatment at lower symptom levels may also reduce the suicide risk Citation[131].

There is little evidence in general that antipsychotic medication has a suicidal preventive effect Citation[46]. However, there is evidence that long-term treatment with antipsychotic drugs is associated with lower mortality in schizophrenia compared with no antipsychotic treatment Citation[132]. Clozapine in particular seems to reduce the risk of suicide Citation[132,133] and suicidal behavior Citation[134]. However, methodological questions have been raised concerning the results reporting the antisuicidal properties of clozapine, and the validity of these results needs to be confirmed in future studies Citation[135]. In addition to clozapine, the only other drug shown to prevent suicide is the mood stabilizer lithium, used primarily in patients with bipolar disorder Citation[136]. However, the effect of lithium on suicidal behavior among patients with schizophrenia is less clear, and it is unknown whether this drug exerts antisuicidal effects among these patients Citation[137].

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is an effective treatment of severe depression, and an acute risk of suicide has been cited as one of the indications for the use of ECT in patients with depression Citation[138]. ECT has been suggested to exert a profound short-term beneficial effect on suicidality Citation[139]. However, there is still no evidence for a direct reduction in completed suicide Citation[140] and there is also a lack of studies among patients with schizophrenia undergoing ECT for the prevention of suicidal behavior. Concurrent depression is a very important risk factor for suicide in schizophrenia, and recent studies have suggested an association between a general decline in suicide risk and usage of antidepressant medication Citation[141,142]. Although the treatment of depression in schizophrenia is crucial, the role of antidepressants in preventing suicide among these patients has not been established Citation[86]. However, antidepressants have been associated with lower all-cause mortality when used in combination with antipsychotics Citation[85]. To facilitate the clinical assessment and treatment of suicide risk in schizophrenia, a treatment algorithm and models showing different pathways to suicide can be used Citation[143,144]. This may be a valuable tool for the clinician. See Box 3 for key issues in clinical assessment of suicide risk.

Together with proper medication, psychosocial interventions and psychotherapy may also be important in addressing specific risk factors and help with coping skills. Bateman reported that cognitive behavioral therapy decreased suicide ideation in patients with schizophrenia Citation[145]. However, to date, there is a lack of empirical evidence on the impact of psychotherapy and related issues, such as therapeutic relationship and counter transference, on suicidal behavior in schizophrenia.

Since suicide risk has been found to be particularly high during the first days after discharge from hospital, a focus on close monitoring and better psychosocial support may be needed during this period Citation[146]. Psychosocial intervention has been found to increase adherence among schizophrenic patients Citation[83]. There is little doubt that these interventions are helpful to improve quality of life, but a direct antisuicidal effect is yet to be proven Citation[147]. There is a need for large randomized clinical trials evaluating the effect of psychosocial treatment on suicide and suicide attempt Citation[129]. Investigation of schizophrenic patients divided into subgroups according to their suicidal motivation has been suggested as one way to use appropriate differentiated preventive and/or treatment measures against suicidal behavior Citation[148].

Expert commentary

Although patients with schizophrenia have the highest mortality risk from suicide, and also high mortality from natural causes of death, the absolute number of suicides is low, and the everyday assessment and prevention of suicide, in both the short- and long-term, remains a difficult and demanding task for the clinician, as well as for society in general. Many well-known risk factors are used for predicting suicide among patients with schizophrenia. However, their limited specificity makes the prediction of future suicide difficult. It is important to recognize that some risk factors among these patients differ compared with risk factors in the general population. Patients with schizophrenia die by suicide at an earlier age, often in close proximity to the onset of illness, and a realistic awareness of the deteriorative effects of the illness and a history of a high level of premorbid function are distinctive and characteristic risk factors for these patients. The suicide risk also appears to remain over a long period of time and since schizophrenia is a chronic disorder, continuous assessment of the suicide risk is important. Comorbid depression and substance abuse is common, and together with male gender and a history of attempted suicide, these are all important risk factors for suicide in schizophrenia. The diagnosis and proper treatment of depression, with both medication and evidence-based psychotherapy, among these patients may be crucial in reducing the suicide risk. Interventions to reduce substance abuse are also important and constitute a major challenge in the clinical setting. Growing evidence for the antisuicidal effect of clozapine places the focus on whether or not the restrictions on the use of clozapine should be reassessed.

Use of adequate medication, continuous working on establishing adherence to medication and special vigilance at periods of high risk are important. The reduction of the number of beds in psychiatric hospitals observed in recent decades and the growing mortality gap between patients with schizophrenia and the general population have to be addressed and discussed with policy makers. Although schizophrenia itself elevates the risk of suicide, it is the presence of additional risk factors that further increase the patient’s risk of suicide. Targeting these individuals at an extra high risk with proper intervention is essential for reducing the overall suicide risk, and constant monitoring of suicide rates in schizophrenia is essential when evaluating the effects of new interventions.

Five-year view

Despite advances in the treatment of psychiatric diseases in recent decades and a general decline in suicides in the western world, suicide is still a major health problem, with approximately 1 million cases per year and an enormous social and economic burden worldwide. The mortality gap between the general population and patients with schizophrenia turns the focus not only to the treatment of the psychiatric disorder itself, but also to somatic diseases and general health interventions with population strategies. Suicide is a major challenge among patients with schizophrenia and, because of the complexity of suicidal behavior, it has become increasingly clear that an integrated approach is needed to attack the problem. Empirically based intervention programs focusing on well-known risk factors, especially for individuals with risk behaviors such as a history of attempted suicide, as well as appropriate use of antipsychotic medication, might help to reduce the mortality and suicide rate. For example, several studies have reported that the use of clozapine reduces suicidal behavior among patients with schizophrenia. The development of psychological interventions, inclusion of biological suicide research, involving neurochemical and genetic phenotypes, development of effective medical treatment and improvement of clinical risk markers of suicide are all important areas of research in the near future. The importance of violent crime and neuropsychiatric diagnoses among patients with schizophrenia as risk factors for suicidal behavior has not been investigated and remain important areas of research. Clinical studies on suicide prevention are, however, often hindered by methodological and ethical problems; for example, the evaluation of risk factors often takes place a long time before suicide occurs and these factors might have changed in the intervening period. Therefore, there is a demand for large randomized clinical trials, as well as prospective trials involving evidence-based approaches. It is also of great importance that the development of evidence-based interventions to prevent suicidal behavior is transferred into the clinical setting and used by those working with patients at risk. The use and development of functional brain imaging techniques make it possible to investigate biochemical alterations and brain circuitry in relation to suicidal behavior. The discovery of neurochemical correlates underlying suicidal behavior may open up new possibilities for pharmacologically acting agents.

Box 1. Definition of schizophrenia.

According to the revised fourth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV-TR) Citation[201], to be diagnosed with schizophrenia, three diagnostic criteria must be met:

Characteristic symptoms

Two or more of the following, each present for much of the time during a 1-month period (or less, if symptoms remitted with treatment):

• Delusions

• Hallucinations

• Disorganized speech, which is a manifestation of formal thought disorder

• Grossly disorganized behavior (e.g., dressing inappropriately, crying frequently) or catatonic behavior

• Negative symptoms: affective flattening (lack or decline in emotional response), alogia (lack or decline in speech) or avolition (lack or decline in motivation)

If the delusions are judged to be bizarre, or if hallucinations consist of hearing one voice participating in a running commentary on the patient’s actions or of hearing two or more voices conversing with each other, only that symptom is required for diagnosis. The speech disorganization criterion is only met if it is severe enough to substantially impair communication.

Social/occupational dysfunction

For a significant portion of the time since the onset of the disturbance, one or more major areas of functioning such as work, interpersonal relations or self-care, are markedly below the level achieved prior to onset.

Duration

Continuous signs of the disturbance persist for at least 6 months. This 6-month period must include at least 1 month of symptoms (or less, if symptoms remitted with treatment).

Schizophrenia cannot be diagnosed if symptoms of mood disorder or pervasive developmental disorder are present, or the symptoms are the direct result of a general medical condition or a substance, such as abuse of a drug or medication.

Box 2. Classification of suicidal behavior.

• Suicide is defined as a self-inflicted death with evidence (either explicit or implicit) that the person intended to die.

• Suicide attempt is defined as self-injurious behavior with a non-fatal outcome accompanied by evidence (either explicit or implicit) that the person intended to die.

• Suicide ideation is defined as thoughts serving the agents of one’s own death. It may vary in seriousness depending on the specificity of suicide plans and the degree of suicidal intent Citation[13].

• Deliberate self-harm is defined as willful self-inflicting of painful, destructive or injurious acts without intent to die Citation[149].

Box 3. Clinical assessment of suicide risk.

• Assessment of risk factors, especially if there is a recent suicide attempt.

• Assessment of current medication for treatment of psychoses and depression.

• If the risk of suicide is high, proper interventions should be made, such as imminent follow-up in an outpatient setting or admittance to hospital.

Key issues

• Schizophrenia is an illness with a high risk of suicide, and the lifetime suicide risk is estimated at 5%.

• The risk of suicide is highest during the first year after the onset of illness and increases in relation to admissions to and discharges from the hospital. The risk of suicide remains over a long period of time.

• Important risk factors are depression and hopelessness, a previous suicide attempt, male gender, poor adherence to treatment and substance abuse.

• High premorbid function, high intelligence quotient and a high level of education increase the risk of suicide.

• An assessment of risk factors is essential to prevent suicidal behavior; however, the low predictive specificity for suicide makes the prevention of future suicide difficult.

• Treatment of depression and substance abuse in patients with schizophrenia is crucial in reducing the risk of suicide. A combination of evidence-based psychosocial intervention and adequate medical treatment might help to reduce suicide rates.

• Clozapine treatment seems to decrease the risk of suicide in patients with schizophrenia. There is a lack of studies among patients with schizophrenia using electroconvulsive therapy and lithium in the prevention of suicide.

• It is crucial that interventions are assessed empirically, and, if found to be effective, transferred into the clinical settings. Continuous assessment of suicide risk is crucial and targeting high-risk individuals is essential.

• Improvements in clinical risk markers for suicide are needed. Future research should focus on the many aspects of suicidal behavior, with a scientific approach and evaluation.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Johannes Kriisa for help with the figure.

Financial & competing interests disclosure

Erik G Jönsson and Jussi Jokinen were partly financed by the Swedish Research Council (K2008-62P-20597-01-3 and K2009-61P-21304-04-4, respectively). The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

References

- MacDonald AW, Schulz SC. What we know: findings that every theory of schizophrenia should explain. Schizophr. Bull.35, 493–508 (2009).

- Dalman C, Thomas HV, David AS, Gentz J, Lewis G, Allebeck P. Signs of asphyxia at birth and risk of schizophrenia. Population-based case–control study. Br. J. Psychiatry179, 403–408 (2001).

- Ichiki M, Kunugi H, Takei N et al. Intra-uterine physical growth in schizophrenia: evidence confirming excess of premature birth. Psychol. Med.30, 597–604 (2000).

- Dalman C, Allebeck P. Paternal age and schizophrenia: further support for an association. Am. J. Psychiatry159, 1591–1592 (2002).

- Bradbury TN, Miller GA. Season of birth in schizophrenia: a review of evidence, methodology, and etiology. Psychol. Bull.98, 569–594 (1985).

- Barr CE, Mednick SA, Munk-Jorgensen P. Exposure to influenza epidemics during gestation and adult schizophrenia. A 40-year study. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry47, 869–874 (1990).

- Dalman C, Allebeck P, Gunnell D et al. Infections in the CNS during childhood and the risk of subsequent psychotic illness: a cohort study of more than one million Swedish subjects. Am. J. Psychiatry165, 59–65 (2008).

- McGrath J, Saha S, Welham J, El Saadi O, MacCauley C, Chant D. A systematic review of the incidence of schizophrenia: the distribution of rates and the influence of sex, urbanicity, migrant status and methodology. BMC Med.2, 13 (2004).

- Sewell RA, Ranganathan M, D’Souza DC. Cannabinoids and psychosis. Int. Rev. Psychiatry21, 152–162 (2009).

- McGrath J, Saha S, Chant D, Welham J. Schizophrenia: a concise overview of incidence, prevalence, and mortality. Epidemiol. Rev.30, 67–76 (2008).

- Aleman A, Kahn RS, Selten JP. Sex differences in the risk of schizophrenia: evidence from meta-analysis. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry60, 565–571 (2003).

- McGrath JJ. Variations in the incidence of schizophrenia: data versus dogma. Schizophr. Bull.32, 195–197 (2006).

- American Psychiatric Association (APA). Practice guideline for the assessment and treatment of patients with suicidal behaviors. Am. J. Psychiatry1–60 (2003).

- Hawton K, van Heeringen K. Suicide. Lancet373, 1372–1381 (2009).

- Hafner H. Gender differences in schizophrenia. Psychoneuroendocrinology28(Suppl. 2), 17–54 (2003).

- Bleuler E. Dementia Praecox or the Group Schizophrenias. International University Press, NY, USA (1950).

- Baxter D, Appleby L. Case register study of suicide risk in mental disorders. Br. J. Psychiatry175, 322–326 (1999).

- Caldwell CB, Gottesman II. Schizophrenics kill themselves too: a review of risk factors for suicide. Schizophr. Bull.16, 571–589 (1990).

- Inskip HM, Harris EC, Barraclough B. Lifetime risk of suicide for affective disorder, alcoholism and schizophrenia. Br. J. Psychiatry172, 35–37 (1998).

- Palmer BA, Pankratz VS, Bostwick JM. The lifetime risk of suicide in schizophrenia: a reexamination. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry62, 247–253 (2005).

- Ösby U, Correia N, Brandt L, Ekbom A, Sparen P. Mortality and causes of death in schizophrenia in Stockholm county, Sweden. Schizophr. Res.45, 21–28 (2000).

- Nordentoft M, Laursen TM, Agerbo E, Qin P, Hoyer EH, Mortensen PB. Change in suicide rates for patients with schizophrenia in Denmark, 1981–1997: nested case–control study. Br. Med. J.329, 261 (2004).

- Saha S, Chant D, McGrath J. A systematic review of mortality in schizophrenia: is the differential mortality gap worsening over time? Arch. Gen. Psychiatry64, 1123–1131 (2007).

- Mortensen PB, Juel K. Mortality and causes of death in first admitted schizophrenic patients. Br. J. Psychiatry163, 183–189 (1993).

- Allebeck P, Varla A, Wistedt B. Suicide and violent death among patients with schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr. Scand.74, 43–49 (1986).

- Brown S. Excess mortality of schizophrenia. A meta-analysis. Br. J. Psychiatry171, 502–508 (1997).

- Mann JJ, Waternaux C, Haas GL, Malone KM. Toward a clinical model of suicidal behavior in psychiatric patients. Am. J. Psychiatry156, 181–189 (1999).

- Turecki G. Dissecting the suicide phenotype: the role of impulsive-aggressive behaviours. J. Psychiatry Neurosci.30, 398–408 (2005).

- Mann JJ. Neurobiology of suicidal behaviour. Nat. Rev. Neurosci.4, 819–828 (2003).

- Preston E, Hansen L. A systematic review of suicide rating scales in schizophrenia. Crisis26, 170–180 (2005).

- Radomsky ED, Haas GL, Mann JJ, Sweeney JA. Suicidal behavior in patients with schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders. Am. J. Psychiatry156, 1590–1595 (1999).

- Kuo CJ, Tsai SY, Lo CH, Wang YP, Chen CC. Risk factors for completed suicide in schizophrenia. J. Clin. Psychiatry66, 579–585 (2005).

- Alaräisänen A, Miettunen J, Rasanen P, Fenton W, Koivumaa-Honkanen HT, Isohanni M. Suicide rate in schizophrenia in the Northern Finland 1966 Birth Cohort. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol.44, 1107–1110 (2009).

- Hawton K, Sutton L, Haw C, Sinclair J, Deeks JJ. Schizophrenia and suicide: systematic review of risk factors. Br. J. Psychiatry187, 9–20 (2005).

- Reutfors J, Brandt L, Jönsson EG, Ekbom A, Sparen P, Ösby U. Risk factors for suicide in schizophrenia: findings from a Swedish population-based case–control study. Schizophr. Res.108, 231–237 (2009).

- Carlborg A, Jokinen J, Jönsson EG, Nordström AL, Nordström P. Long-term suicide risk in schizophrenia spectrum psychoses: survival analysis by gender. Arch. Suicide Res.12, 347–351 (2008).

- Heilä H, Isometsä ET, Henriksson MM, Heikkinen ME, Marttunen MJ, Lönnqvist JK. Suicide and schizophrenia: a nationwide psychological autopsy study on age- and sex-specific clinical characteristics of 92 suicide victims with schizophrenia. Am. J. Psychiatry154, 1235–1242 (1997).

- Qin P, Nordentoft M. Suicide risk in relation to psychiatric hospitalization: evidence based on longitudinal registers. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry62, 427–432 (2005).

- Ho TP. The suicide risk of discharged psychiatric patients. J. Clin. Psychiatry64, 702–707 (2003).

- Reutfors J, Brandt L, Ekbom A, Isacsson G, Sparen P, Ösby U. Suicide and hospitalization for mental disorders in Sweden: a population-based case–control study. J. Psychiatr. Res. DOI:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.02.003 (2010) (Epub ahead of print).

- Roy A. Suicide in chronic schizophrenia. Br. J. Psychiatry141, 171–177 (1982).

- Yarden PE. Observations on suicide in chronic schizophrenics. Compr. Psychiatry15, 325–333 (1974).

- Lee HC, Lin HC. Are psychiatrist characteristics associated with postdischarge suicide of schizophrenia patients? Schizophr. Bull.35, 760–765 (2009).

- Hansen V, Jacobsen BK, Arnesen E. Cause-specific mortality in psychiatric patients after deinstitutionalisation. Br. J. Psychiatry179, 438–443 (2001).

- Seeman MV. An outcome measure in schizophrenia: mortality. Can. J. Psychiatry52, 55–60 (2007).

- Pompili M, Amador XF, Girardi P et al. Suicide risk in schizophrenia: learning from the past to change the future. Ann. Gen. Psychiatry6, 10 (2007).

- Cavanagh JT, Carson AJ, Sharpe M, Lawrie SM. Psychological autopsy studies of suicide: a systematic review. Psychol. Med.33, 395–405 (2003).

- Carlborg A, Jokinen J, Nordström AL, Jönsson EG, Nordström P. Attempted suicide predicts suicide risk in schizophrenia spectrum psychosis. Nord. J. Psychiatry64, 68–72 (2009).

- Harris EC, Barraclough B. Suicide as an outcome for mental disorders. A meta-analysis. Br. J. Psychiatry170, 205–228 (1997).

- Tidemalm D, Langström N, Lichtenstein P, Runeson B. Risk of suicide after suicide attempt according to coexisting psychiatric disorder: Swedish cohort study with long term follow-up. Br. Med. J.337, a2205 (2008).

- Harkavy-Friedman JM, Restifo K, Malaspina D et al. Suicidal behavior in schizophrenia: characteristics of individuals who had and had not attempted suicide. Am. J. Psychiatry156, 1276–1278 (1999).

- Hunt IM, Kapur N, Windfuhr K et al. Suicide in schizophrenia: findings from a national clinical survey. J. Psychiatr. Pract.12, 139–147 (2006).

- Gupta S, Black DW, Arndt S, Hubbard WC, Andreasen NC. Factors associated with suicide attempts among patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatric Services49, 1353–1355 (1998).

- Roy A, Mazonson A, Pickar D. Attempted suicide in chronic schizophrenia. Br. J. Psychiatry144, 303–306 (1984).

- Haw C, Hawton K, Sutton L, Sinclair J, Deeks J. Schizophrenia and deliberate self-harm: a systematic review of risk factors. Suicide Life Threat. Behav.35, 50–62 (2005).

- Drake RE, Gates C, Cotton PG. Suicide among schizophrenics: a comparison of attempters and completed suicides. Br. J. Psychiatry149, 784–787 (1986).

- Harkavy-Friedman JM, Nelson EA, Venarde DF, Mann JJ. Suicidal behavior in schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder: examining the role of depression. Suicide Life Threat. Behav.34, 66–76 (2004).

- Jones JS, Stein DJ, Stanley B, Guido JR, Winchel R, Stanley M. Negative and depressive symptoms in suicidal schizophrenics. Acta Psychiatr. Scand.89, 81–87 (1994).

- Nordentoft M, Jeppesen P, Abel M et al. OPUS study: suicidal behaviour, suicidal ideation and hopelessness among patients with first-episode psychosis. One-year follow-up of a randomised controlled trial. Br. J. Psychiatry Suppl.43, S98–S106 (2002).

- Limosin F, Loze JY, Philippe A, Casadebaig F, Rouillon F. Ten-year prospective follow-up study of the mortality by suicide in schizophrenic patients. Schizophr. Res.94, 23–28 (2007).

- Gut-Fayand A, Dervaux A, Olie JP, Loo H, Poirier MF, Krebs MO. Substance abuse and suicidality in schizophrenia: a common risk factor linked to impulsivity. Psychiatry Res.102, 65–72 (2001).

- Barbee JG, Clark PD, Crapanzano MS, Heintz GC, Kehoe CE. Alcohol and substance abuse among schizophrenic patients presenting to an emergency psychiatric service. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis.177, 400–407 (1989).

- Mauri MC, Volonteri LS, De Gaspari IF, Colasanti A, Brambilla MA, Cerruti L. Substance abuse in first-episode schizophrenic patients: a retrospective study. Clin. Pract. Epidemol. Ment. Health2, 4 (2006).

- Compton MT, Kelley ME, Ramsay CE et al. Association of pre-onset cannabis, alcohol, and tobacco use with age at onset of prodrome and age at onset of psychosis in first-episode patients. Am. J. Psychiatry166, 1251–1257 (2009).

- Zammit S, Allebeck P, Andreasson S, Lundberg I, Lewis G. Self reported cannabis use as a risk factor for schizophrenia in Swedish conscripts of 1969: historical cohort study. Br. Med. J.325, 1199 (2002).

- Miller R, Ream G, McCormack J, Gunduz-Bruce H, Sevy S, Robinson D. A prospective study of cannabis use as a risk factor for non-adherence and treatment dropout in first-episode schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res.113, 138–144 (2009).

- Cantwell R. Substance use and schizophrenia: effects on symptoms, social functioning and service use. Br. J. Psychiatry182, 324–329 (2003).

- Zisook S, Heaton R, Moranville J, Kuck J, Jernigan T, Braff D. Past substance abuse and clinical course of schizophrenia. Am. J. Psychiatry149, 552–553 (1992).

- Caton CL, Shrout PE, Eagle PF, Opler LA, Felix A, Dominguez B. Risk factors for homelessness among schizophrenic men: a case–control study. Am. J. Public Health84, 265–270 (1994).

- Drake RE, Wallach MA, Teague GB, Freeman DH, Paskus TS, Clark TA. Housing instability and homelessness among rural schizophrenic patients. Am. J. Psychiatry148, 330–336 (1991).

- Menezes PR, Johnson S, Thornicroft G et al. Drug and alcohol problems among individuals with severe mental illness in south London. Br. J. Psychiatry168, 612–619 (1996).

- Duke PJ, Pantelis C, Barnes TR. South Westminster schizophrenia survey. Alcohol use and its relationship to symptoms, tardive dyskinesia and illness onset. Br. J. Psychiatry164, 630–636 (1994).

- Scott H, Johnson S, Menezes P et al. Substance misuse and risk of aggression and offending among the severely mentally ill. Br. J. Psychiatry172, 345–350 (1998).

- Fazel S, Grann M, Carlström E, Lichtenstein P, Långström N. Risk factors for violent crime in Schizophrenia: a national cohort study of 13,806 patients. J. Clin. Psychiatry70, 362–369 (2009).

- Fazel S, Långström N, Hjern A, Grann M, Lichtenstein P. Schizophrenia, substance abuse, and violent crime. JAMA301, 2016–2023 (2009).

- Fenton WS. Depression, suicide, and suicide prevention in schizophrenia. Suicide Life Threat. Behav.30, 34–49 (2000).

- De Hert M, McKenzie K, Peuskens J. Risk factors for suicide in young people suffering from schizophrenia: a long-term follow-up study. Schizophr. Res.47, 127–134 (2001).

- Drake RE, Gates C, Cotton PG, Whitaker A. Suicide among schizophrenics. Who is at risk? J. Nerv. Ment. Dis.172, 613–617 (1984).

- Alaräisänen A, Miettunen J, Lauronen E, Rasanen P, Isohanni M. Good school performance is a risk factor of suicide in psychoses: a 35-year follow up of the Northern Finland 1966 Birth Cohort. Acta Psychiatr. Scand.114, 357–362 (2006).

- Montross LP, Zisook S, Kasckow J. Suicide among patients with schizophrenia: a consideration of risk and protective factors. Ann. Clin. Psychiatry17, 173–182 (2005).

- Bourgeois M, Swendsen J, Young F et al. Awareness of disorder and suicide risk in the treatment of schizophrenia: results of the international suicide prevention trial. Am. J. Psychiatry161, 1494–1496 (2004).

- Kim CH, Jayathilake K, Meltzer HY. Hopelessness, neurocognitive function, and insight in schizophrenia: relationship to suicidal behavior. Schizophr. Res.60, 71–80 (2003).

- Leucht S, Heres S. Epidemiology, clinical consequences, and psychosocial treatment of nonadherence in schizophrenia. J. Clin. Psychiatry67(Suppl. 5), 3–8 (2006).

- Novick D, Haro JM, Suarez D, Perez V, Dittmann RW, Haddad PM. Predictors and clinical consequences of non-adherence with antipsychotic medication in the outpatient treatment of schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res.176(2–3), 109–113 (2010).

- Haukka J, Tiihonen J, Härkänen T, Lönnqvist J. Association between medication and risk of suicide, attempted suicide and death in nationwide cohort of suicidal patients with schizophrenia. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf.17, 686–696 (2008).

- Pompili M, Lester D, Innamorati M, Tatarelli R, Girardi P. Assessment and treatment of suicide risk in schizophrenia. Expert Rev. Neurother.8, 51–74 (2008).

- Taiminen TJ, Kujari H. Antipsychotic medication and suicide risk among schizophrenic and paranoid inpatients. A controlled retrospective study. Acta Psychiatr. Scand.90, 247–251 (1994).

- Lester D. Sex differences in completed suicide by schizophrenic patients: a meta-analysis. Suicide Life Threat. Behav.36, 50–56 (2006).

- Canetto SS. Women and suicidal behavior: a cultural analysis. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry78, 259–266 (2008).

- Liu KY, Chen EY, Cheung AS, Yip PS. Psychiatric history modifies the gender ratio of suicide: an East and West comparison. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol.44, 130–134 (2009).

- Yip PS, Callanan C, Yuen HP. Urban/rural and gender differentials in suicide rates: east and west. J. Affect. Disord.57, 99–106 (2000).

- von Borczyskowski A, Lindblad F, Vinnerljung B, Hjern A. Gender differences in risk factors for suicide: findings from a Swedish national cohort study. Can. J. Psychiatry55(2), 108–111 (2009).

- Karvonen K, Sammela HL, Rahikkala H et al. Sex, timing, and depression among suicide victims with schizophrenia. Compr. Psychiatry48, 319–322 (2007).

- Salokangas RK. Prognostic implications of the sex of schizophrenic patients. Br. J. Psychiatry142, 145–151 (1983).

- Seeman MV. Suicide among women with schizophrenia spectrum disorders. J. Psychiatr. Pract.15, 235–242 (2009).

- Goodwin R, Lyons JS, McNally RJ. Panic attacks in schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res.58, 213–220 (2002).

- Hu WH, Sun CM, Lee CT, Peng SL, Lin SK, Shen WW. A clinical study of schizophrenic suicides. 42 cases in Taiwan. Schizophr. Res.5, 43–50 (1991).

- Baca-Garcia E, Perez-Rodriguez MM, Diaz Sastre C, Saiz-Ruiz J, de Leon J. Suicidal behavior in schizophrenia and depression: a comparison. Schizophr. Res.75, 77–81 (2005).

- Mann JJ, Currier D, Stanley B, Oquendo MA, Amsel LV, Ellis SP. Can biological tests assist prediction of suicide in mood disorders? Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol.9, 465–474 (2006).

- Nordström P, Samuelsson M, Åsberg M et al. CSF 5-HIAA predicts suicide risk after attempted suicide. Suicide Life Threat. Behav.24, 1–9 (1994).

- Åsberg M. Neurotransmitters and suicidal behavior. The evidence from cerebrospinal fluid studies. Ann. NY Acad. Sci.836, 158–181 (1997).

- Lester D. The concentration of neurotransmitter metabolites in the cerebrospinal fluid of suicidal individuals: a meta-analysis. Pharmacopsychiatry28, 45–50 (1995).

- Engström G, Alling C, Blennow K, Regnell G, Träskman-Bendz L. Reduced cerebrospinal HVA concentrations and HVA/5-HIAA ratios in suicide attempters. Monoamine metabolites in 120 suicide attempters and 47 controls. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol.9, 399–405 (1999).

- Jokinen J, Nordström AL, Nordström P. The relationship between CSF HVA/5-HIAA ratio and suicide intent in suicide attempters. Arch. Suicide Res.11, 187–192 (2007).

- Roy A, Ågren H, Pickar D et al. Reduced CSF concentrations of homovanillic acid and homovanillic acid to 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid ratios in depressed patients: relationship to suicidal behavior and dexamethasone nonsuppression. Am. J. Psychiatry143, 1539–1545 (1986).

- Mann JJ, Malone KM, Psych MR et al. Attempted suicide characteristics and cerebrospinal fluid amine metabolites in depressed inpatients. Neuropsychopharmacology15, 576–586 (1996).

- Träskman-Bendz L, Alling C, Oreland L, Regnell G, Vinge E, Öhman R. Prediction of suicidal behavior from biologic tests. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol.12, S21–S26 (1992).

- Placidi GP, Oquendo MA, Malone KM, Huang YY, Ellis SP, Mann JJ. Aggressivity, suicide attempts, and depression: relationship to cerebrospinal fluid monoamine metabolite levels. Biol. Psychiatry50, 783–791 (2001).

- Carlborg A, Jokinen J, Nordström AL, Jönsson EG, Nordström P. CSF 5-HIAA, attempted suicide and suicide risk in schizophrenia spectrum psychosis. Schizophr. Res.112, 80–85 (2009).

- Marcinko D, Pivac N, Martinac M, Jakovljevic M, Mihaljevic-Peles A, Muck-Seler D. Platelet serotonin and serum cholesterol concentrations in suicidal and non-suicidal male patients with a first episode of psychosis. Psychiatry Res.150, 105–108 (2007).

- Jokinen J, Carlborg A, Mårtensson B, Forslund K, Nordström AL, Nordström P. DST non-suppression predicts suicide after attempted suicide. Psychiatry Res.150, 297–303 (2007).

- Plocka-Lewandowska M, Araszkiewicz A, Rybakowski JK. Dexamethasone suppression test and suicide attempts in schizophrenic patients. Eur. Psychiatry16, 428–431 (2001).

- Lewis CF, Tandon R, Shipley JE et al. Biological predictors of suicidality in schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr. Scand.94, 416–420 (1996).

- Pickar D, Roy A, Breier A et al. Suicide and aggression in schizophrenia. Neurobiologic correlates. Ann. NY Acad. Sci.487, 189–196 (1986).

- Baldessarini RJ, Hennen J. Genetics of suicide: an overview. Harv. Rev. Psychiatry12, 1–13 (2004).

- Courtet P, Jollant F, Castelnau D, Buresi C, Malafosse A. Suicidal behavior: relationship between phenotype and serotonergic genotype. Am. J. Med. Genet. C Semin. Med. Genet.133C, 25–33 (2005).

- Qin P, Agerbo E, Mortensen PB. Suicide risk in relation to family history of completed suicide and psychiatric disorders: a nested case–control study based on longitudinal registers. Lancet360, 1126–1130 (2002).

- Runeson B, Åsberg M. Family history of suicide among suicide victims. Am. J. Psychiatry160, 1525–1526 (2003).

- Li D, He L. Meta-analysis supports association between serotonin transporter (5-HTT) and suicidal behavior. Mol. Psychiatry12, 47–54 (2007).

- Li D, Duan Y, He L. Association study of serotonin 2A receptor (5-HT2A) gene with schizophrenia and suicidal behavior using systematic meta-analysis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun.340, 1006–1015 (2006).

- Saetre P, Lundmark P, Wang A et al. The tryptophan hydroxylase 1 (TPH1) gene, schizophrenia susceptibility, and suicidal behavior: A multi-centre case–control study and meta-analysis. Am. J. Med. Genet. B Neuropsychiatr. Genet.153B, 387–396 (2010).

- Fanous AH, Chen X, Wang X et al. Genetic variation in the serotonin 2A receptor and suicidal ideation in a sample of 270 Irish high-density schizophrenia families. Am. J. Med. Genet. B Neuropsychiatr. Genet.150B, 411–417 (2009).

- De Luca V, Tharmalingam S, Zai C et al. Association of HPA axis genes with suicidal behaviour in schizophrenia. J. Psychopharmacol.24(5), 677–682 (2010).

- Feldcamp LA, Souza RP, Romano-Silva M, Kennedy JL, Wong AH. Reduced prefrontal cortex DARPP-32 mRNA in completed suicide victims with schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res.103, 192–200 (2008).

- Wasserman D, Terenius L, Wasserman J, Sokolowski M. The 2009 Nobel conference on the role of genetics in promoting suicide prevention and the mental health of the population. Mol. Psychiatry15, 12–17 (2010).

- Aguilar EJ, Garcia-Marti G, Marti-Bonmati L et al. Left orbitofrontal and superior temporal gyrus structural changes associated to suicidal behavior in patients with schizophrenia. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry32, 1673–1676 (2008).

- Rusch N, Spoletini I, Wilke M et al. Inferior frontal white matter volume and suicidality in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res.164, 206–214 (2008).

- Maris RW, Berman A, Silverman MM. Treatment and prevention of suicide. In: Comprehensive Textbook of Suicidology. Maris RW, Berman A, Silverman MM (Eds). Guilford Press, NY, USA (2000).

- Nordentoft M. Prevention of suicide and attempted suicide in Denmark. Epidemiological studies of suicide and intervention studies in selected risk groups. Dan. Med. Bull.54, 306–369 (2007).

- Mann JJ, Apter A, Bertolote J et al. Suicide prevention strategies: a systematic review. JAMA294, 2064–2074 (2005).

- Melle I, Johannesen JO, Friis S et al. Early detection of the first episode of schizophrenia and suicidal behavior. Am. J. Psychiatry163, 800–804 (2006).

- Tiihonen J, Lönnqvist J, Wahlbeck K et al. 11-year follow-up of mortality in patients with schizophrenia: a population-based cohort study (FIN11 study). Lancet374, 620–627 (2009).

- Altamura AC, Anand R, Bertoldi A et al. Clozapine treatment for suicidality in schizophrenia: International Suicide Prevention Trial (InterSePT). Arch. Gen. Psychiatry60, 82–91 (2003).

- Hennen J, Baldessarini RJ. Suicidal risk during treatment with clozapine: a meta-analysis. Schizophr. Res.73, 139–145 (2005).

- De Hert M, Correll CU, Cohen D. Do antipsychotic medications reduce or increase mortality in schizophrenia? A critical appraisal of the FIN-11 study. Schizophr. Res.117, 68–74 (2010).

- Cipriani A, Pretty H, Hawton K, Geddes JR. Lithium in the prevention of suicidal behavior and all-cause mortality in patients with mood disorders: a systematic review of randomized trials. Am. J. Psychiatry162, 1805–1819 (2005).

- Leucht S, McGrath J, Kissling W. Lithium for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev.3, CD003834 (2003).

- Sharma V. The effect of electroconvulsive therapy on suicide risk in patients with mood disorders. Can. J. Psychiatry46, 704–709 (2001).

- Prudic J, Sackeim HA. Electroconvulsive therapy and suicide risk. J. Clin. Psychiatry60(Suppl. 2), 104–110; discussion 111–106 (1999).

- Popeo DM. Electroconvulsive therapy for depressive episodes: a brief review. Geriatrics64, 9–12 (2009).

- Henriksson S, Isacsson G. Increased antidepressant use and fewer suicides in Jämtland county, Sweden, after a primary care educational programme on the treatment of depression. Acta Psychiatr. Scand.114, 159–167 (2006).

- Isacsson G, Rich CL. Antidepressant drug use and suicide prevention. Int. Rev. Psychiatry17, 153–162 (2005).

- Alaräisänen A, Heikkinen J, Kianickova Z, Miettunen J, Räsänen P, Isohanni M. Pathways leading to suicide in schizophrenia. Curr. Psych. Rev.3, 233–242 (2007).

- Meltzer H, Conley R, De Leo D et al. Intervention strategies for suicidality. J. Clin. Psychiatry Audiograph Series6, 1–18 (2003).

- Bateman K, Hansen L, Turkington D, Kingdon D. Cognitive behavioral therapy reduces suicidal ideation in schizophrenia: results from a randomized controlled trial. Suicide Life Threat. Behav.37, 284–290 (2007).

- Rossau CD, Mortensen PB. Risk factors for suicide in patients with schizophrenia: nested case–control study. Br. J. Psychiatry171, 355–359 (1997).

- De Leo D, Spathonis K. Do psychosocial and pharmacological interventions reduce sucide in schizophrenia and schizophrenia spectrum disorders? Arch. Suicide Res.7(4), 353–374 (2003).

- Acosta FJ, Aguilar EJ, Cejas MR, Gracia R, Caballero-Hidalgo A, Siris SG. Are there subtypes of suicidal schizophrenia? A prospective study. Schizophr. Res.86, 215–220 (2006).

- Skegg K. Self-harm. Lancet366, 1471–1483 (2005).

Websites

- American Psychiatric Association www.psych.org

- World Health Organization www.who.org